CLICK

How Sam Youkilis Captures the World with Five iPhones

In 2016, Instagram added a feature called Stories, which began as an obvious Snapchat knockoff but quickly became an engine for constant expression. Around the same time, Sam Youkilis moved back to his native Manhattan after graduating from Bard College’s photo department, led by Stephen Shore. As he worked to gain a foothold in the art world, Youkilis realized that Instagram was the perfect home for his images, which increasingly fixated on time and movement.

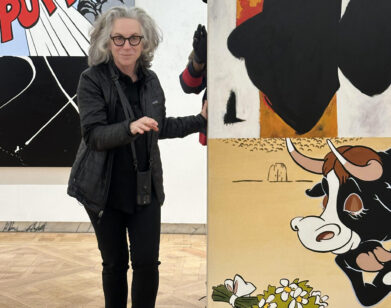

Youkilis soon left New York and began criss-crossing the globe, spending a majority of his time in Mexico and Italy, which is now his home base. Every step of the way the now 30-year-old trains his camera—well, actually, his iPhone—on the people around him. Blurring the line between travel photography and anthropology, his work is informed by an acute attention to light, color, and framing, as well as his discreetly observant eye for quiet and often humorous moments of humanity.

Six years of travel is compiled in his debut monograph, Somewhere, out next month via Loose Joints. The 500-page tome loosely follows a day-in-the-life format, opening with Xochimilco sunrises and ending with lavish Italian dinner spreads and sunsets. Along the way are delightful interludes like “Exercising in public,” “Butchers with obscured faces,” and “Animals where they shouldn’t be.” A few weeks before the launch of Somewhere, I caught up with the photographer about social media, carrying multiple iPhones, and getting lost in the archives.

———

QUINN MORELAND: Hey, Sam. How’s it going?

SAM YOUKILIS: Things are good. I’m in Positano right now. Vacation-ish.

MORELAND: Are you a good packer?

YOUKILIS: Packing is extremely hard. I’m lucky that I’m working so much as a commercial fashion photographer, but I’m shooting almost everything on a phone so I have almost no equipment. I’ll bring a 35-millimeter rangefinder, point and shoot camera, and that’s kind of all that I’m carrying with me, camera-wise. I’m not great at packing and I’m not getting any better at it. I am getting better at flying. Checking a bag, always. Bringing too many clothes. I’m not a great packer.

MORELAND: These are the hard-hitting questions.

YOUKILIS: It’s extremely good.

MORELAND: How many phones do you have?

YOUKILIS: Well, I have five or six phones. I only bring two of them with me. I mean, the iPhone 15 Pro just came out, so I started shooting with that the day after my birthday. I like to have two of whatever the newest phone is, one is a backup in case my phone stops working, or in case I drop it in the water thinking it’s nice to film a reflection.

MORELAND: Has that happened?

YOUKILIS: No.

MORELAND: That’s good.

YOUKILIS: I think it’s becoming more and more commonplace that people are using iPhones to make commercial work. Even a couple of years ago, when I first started showing up to a set with a phone, people were like, “What the hell?” But now, it’s quite normal and there’s no sort of bad connotation.

MORELAND: Are you strictly an Apple person? I know that Samsung is quite proud of their camera phone, which is supposedly the best.

YOUKILIS: I don’t think I’m choosing the iPhone camera phone because it’s the best that there is. That’s not really the point. I used to travel with two D-800s with telephoto lens and my back would be fucked right now if I didn’t adapt what I was using. I literally walk 10 to 15 miles a day and observe and notice things. And my job is just to record those things and share them with anyone who’s interested. This is the same thing I’ve been doing forever. It’s just slowly migrating from a very heavy, long camera to something that I think better fits my practice at this specific moment in time better, which is a phone.

MORELAND: You’ve clearly found your medium and had a lot of success on Instagram. But being tied to social media inherently has its difficulties. You’re kind of at the whim of Instagram’s algorithm and its formal restraints. So I’m curious what your relationship is with social media.

YOUKILIS: Obviously, it’s a blessing and a curse. It’s how we and our generation and the clients I’m working for, and their audience, for the most part, are consuming media and imagery more than almost ever before. So my stuff is so well-fashioned and so well-outfitted for Instagram. It lives there really well. I mean, I started making videos because of Instagram stories. They were initially an accompaniment or a form of proof to my stills and would be presented as this sort of temporal or ephemeral thing. So I think my practice shifted from being a mix of horizontal and vertical to almost always thinking and framing the world in a vertical way. Hold on, I think I lost the thread.

MORELAND: That’s a good general answer to what appeals to you.

YOUKILIS: I mean, I’m lucky that I’ve been able to find success in what I do on Instagram in a really organic way. And I am lucky that I’m able to share my work in a diaristic way where it’s very much an insight into my life from morning to the end of the day. Actually, I also use this as sort of the framework for the structuring of the book, because I wanted it to somehow mirror this abundance of things that I’m showing from the morning to the evening. It’s quite obvious structurally, but I really liked that there was a sort of echo between that and the way I share work on Instagram.

MORELAND: If we can jump back two decades, how did you get interested in photography?

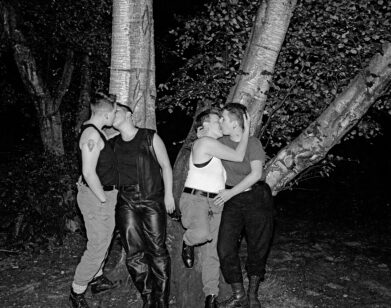

YOUKILIS: I was gifted a film camera. This is actually funny, because these are the days when some friends and I would go around with our respective cameras as the de facto group photographers of our social group. Like any kid growing up in New York, I felt like what we were doing was somehow important enough that we needed to memorialize it. It was interesting that we were drinking, smoking, breaking into subway tunnels—all this stuff that is so cliché. We were watching things like Kids, and looking at Tulsa by Larry Clark, these very funny 13-14 year-old classic New York City kid points of inspiration. But I think part of the reason it resonates with so many people is because it’s so literally what’s in front of us. I’ve never been that kind of photographer who’s making still lives, composing things. All my work has always been extremely analytical. Whatever’s happening, I want to document. I want to preserve this thing that otherwise would be lost. And the camera, for me, is proof or evidence of a thing that is happening or unfolding in real time, and a way to cement it. I had some social anxiety and still do a lot of the time and the camera was a way for me to feel more comfortable, to give me purpose in a setting. I’d have some silly fear that what I was giving to conversation or the space was not interesting enough in itself, that I somehow had to provide this other thing, so it was a bit out of anxiety and security as well.

MORELAND: So the book is small, right? Small, but dense. And it’s the size of an iPhone-ish.

YOUKILIS: It’s bigger than an iPhone. I don’t think the iPhone aspect ratio is particularly appealing as a physical thing. I wanted to reference both the postcard and the iPhone in the format of the book. So it’s kind of in between the two.

MORELAND: Were there any photo books that you looked to as a guide?

YOUKILIS: There’s a book called Pasolini’s Bodies and Places that drew stills from all of his different films and organized them into categories based on different human modes of behavior, gestures and very specific actions. So much of what I shoot is serial and about building meaning through repetition. And I’m very often thinking thematically, sometimes consciously, sometimes more subliminally. The pandemic was actually a really interesting moment for me because I couldn’t move the way I wanted to move. And if I did move, I was seeing way less because there just wasn’t much happening around me. It was one of the first times I had to stay still and try to make work by scouring an archive instead of actively going out and making work. So it really gave me time to try to find threads and links between the work I had been making over the last years instead of continuing to produce. Bodies and Places is the most direct reference [in that it’s] a typology that I wanted to use. But I also wanted themes that were extremely literal and things that were really ambiguous to play side by side. Some things in gestures of romance could fall into the category of kisses. Some things in yellow could also fall into flowers. I wanted there to be overlap and figure out where things fit best.

MORELAND: There’s this absurdity in some of the things that you capture, like the section of the book about hand sanitizer at Cipriani. I’m sure you could do a monograph focused around a theme of Italy, some sort of big picture thing, but what you just said speaks so much more to the way you function. There’s just a lot.

YOUKILIS: It is a lot. I don’t mean to be cleverly self-deprecating in any sort of way. I’m humbled that people appreciate my work. I’m humbled that I have an audience. I truly cannot believe that I am making a book. And this book I’ve made is a mammoth of a book. I don’t mind if people look at it in segments. Really, I want to make light-hearted imagery that’s easy to look at.

MORELAND: How did you go about editing?

YOUKILIS: Literally, it was one of the hardest processes of my life. I’ve never worked an office job. After graduating from college I would go out all day and make work and then work restaurant jobs. And now, I can work professionally as a photographer, which also means just moving and shooting all day. So, for a week making the book, I had to sit in an office, scour my archive, and be in one place for nine hours sitting in a chair, which I haven’t actually done in my adult life besides flying. Which is insane to say. So it was really difficult for me to sit still and do this. I think I have really bad attention-deficit disorder and need movement and to look at things and do things, otherwise I start to go a little bit stir-crazy.

MORELAND: It kind of reminds me of what they say about learning a language. The best thing to do is just to get out and use the language. And so much of how you seem to carry yourself as a photographer is just by leaving your house and being among people and experiencing the world.

YOUKILIS: Completely, completely. I think it’s exactly like learning a language.

MORELAND: How many languages are you speaking these days?

YOUKILIS: I speak Italian and Spanish. Not perfectly. I can’t write or do an interview in either of them, but I can communicate quite well in both.

MORELAND: So, I do want to ask the thing everyone asks you, which is approaching your subjects and asking for permission. How do you explain what you’re doing? Recently, I was reading an interview with Daniel Arnold and he was like, “I don’t ask for permission.” But your work is extremely different.

YOUKILIS: It’s a really good question. I have been asked about it a lot.

MORELAND: I’m sure.

YOUKILIS: I mean, I have a shitty—not a shitty answer, but a basic answer, which is that I approach everything quite differently. Daniel is a really good friend. I love so much of his work. And I think, often, my work is a really similar approach in that it’s analytical and drawing from the world around me. I see things happening in real time and my work is a response to those things. And in these cases, if I see someone who’s about to step into a hole in the street that they don’t see and fall—this is a bad example, because this sounds ethically not so nice, but I know that there’s certain things I can’t recreate. I know that there’s no reason for me to ask someone to take a picture that might imply their humiliation. And if they see me and want to talk to me about why I did that, I’m happy to talk to them a little bit about my practice. More often than not, they’re like, “Oh, that’s really funny. Leave it. It doesn’t matter.” But another big part of my practice is actually making friends, communicating with people, building trust and making work that’s about breaking this barrier between strangers. And in these cases, I’m asking and explaining. I can’t control the ultimate circulation or dissemination of an image. This is the world and time that we live in. But it’s so much trust and it’s so much responsibility, and it’s something I do think about all of the time.

Somewhere by Sam Youkilis is published by Loose Joints.