STUDIO VISIT

How Painter Anthony Cudahy Finds Intimacy In The Mundane

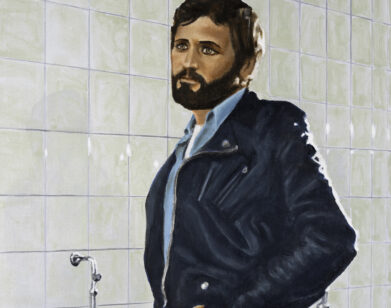

Anthony Cudahy, photographed by Jack Pierson.

Painter Anthony Cudahy doesn’t think he’s “made it,” but some would say otherwise. Recently, a friend of mine told me that “making it” for an artist means they’re afforded the luxury of time off from the constant rush of ideation and production. Going by that standard, Cudahy has not only “made it” but is well on his way to stardom.

If you’ve had the pleasure of seeing one of his paintings — online or, even better, in person—you’ll understand what I’m talking about. Cudahy, who paints narrative, collage-like paintings that suggest queer intimacy in the mundane. On his canvases, color, form, and composition mingle with archetypal figures drawn from his own life to create sprawling, emotional landscapes. His multifaceted approach to figurative painting challenges traditional conventions of representation with an openness that’s both rigorous and romantic. “The fact that we have flat digital space now doesn’t negate and remove older ways of conceiving or representing space,” Cudahy told me. “I think I’m interested in just having a multiplicity of kinds of space.” When we got together earlier this month to mark his new solo exhibition, on view until January 26th at the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas, Cudahy and I discussed the blurred edges of memory and technology, the queer gaze in relation to the self, and, of course, our shared adoration for Blood Orange.

———

ISABELLA ARIAS: Can you tell me what you’ve been listening to right now, music-wise?

ANTHONY CUDAHY: Yes. I’ve been doing a deep dive into Mariah Carey recently. I have been listening to the new Mount Eerie album a lot. I feel like I’ve been reconnecting with a lot of music from 10 or so years ago. I’ve been listening to a lot of Blood Orange, which feels like a very specific time in my life in New York City. It feels very nostalgic.

ARIAS: I love Blood Orange. He’s one of my favorites of all time. So do you listen to music when you paint?

CUDAHY: Yes. I go through really long periods of listening to music while I’m making work, and then periods where I can’t and I need to listen to something like interviews or podcasts. I feel like when I’m in a better place mentally, I’m more into music. Because when you’re painting, you’re alone for such a long time with your thoughts and if you’re in a really good place, music is perfect for that. If not, you can really spiral.

ARIAS: That makes sense. I read that music has a big effect on your work and it’s inspired you a lot. Actually, while I was doing research for this interview last night, I listened to the whole album First Thought Best Thought by Arthur Russell because I was looking at your painting, Arthur Russel on the Shore (2023), which I absolutely adore. Could you tell me a bit about how you created that painting and the effect that that musician has had on you?

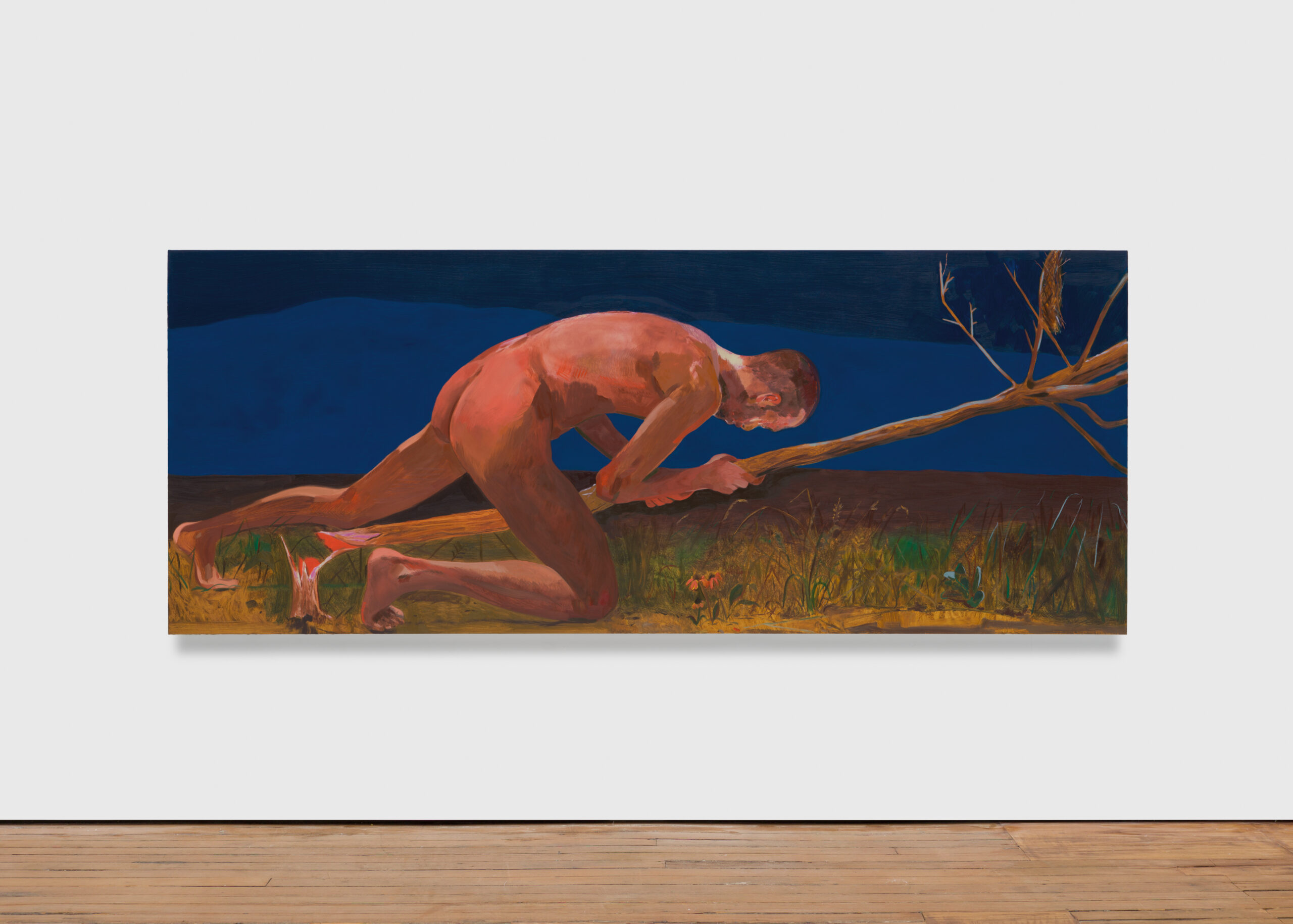

Death instinct (for Bergman, for Tarkovsky), 2024. Oil on linen. 121.9 x 304.8 cm | 48 x 120 in.

CUDAHY: Sure. On an emotional level, there are certain musicians who, when they tap into a wavelength that you’re on, it’s like you so deeply feel it. And Russell’s sensibility transcends his genre explorations. One of the things that I love about him is that there really isn’t a hierarchy or a set of rules for what he pulls from or is inspired by. I’ve always felt that he tapped into this really deep, unique place, and that’s kind of what the painting was about. On one level, it’s a very ghostly portrayal of him. Most of the painting is this sort of muted blue zone that’s maybe a little foggy or smoky. There’s distance with this figure from the past. But where it’s kind of electric is his foot touching this stream, and I was thinking of that as a point of connection through which he’s able to tap into people currently. It’s like a living thing.

ARIAS: Do you find that when you’re painting, you have a set of rules for yourself, or do you think you tend more to the Arthur Russell way of creating?

CUDAHY: Especially in the past few years, I’ve really been trying to forget a lot of those things that get drilled into your head. When I first started painting, the world of painting and also the New York art world were very different. To be a painter, you had to be like Luc Tuymans or have this sort of conceptual framework for why you’re painting and why you’re interested in what you’re interested in. You needed the very long artist statement and you needed to make all these limitations and rules for yourself because it was embarrassing to admit that you just really romantically liked color and the history of painting and figurative work. Some of that is still in there, just by virtue of my first interactions with contemporary painters. But I’m always trying to push past that and be like, “Why am I resistant to doing this thing that feels intrinsic to me?” So I feel like lately, I’m trying to have these really broad, open-ended questions and goals instead. A few years ago, I had this idea of painting a dissolved figure. I was looking at painters like Vuillard and how the figures interacted with the spaces that they were in and what that said about light or representations of space that wasn’t like what we consider more contemporaneous space. I went at that idea from so many different directions and made so many different kinds of paintings for it. None of them actually resolved the question, but I just like these more open-ended, impossible questions versus setting up rules and parameters.

ARIAS: And when I see your paintings, you would think that the figure would of course be the protagonist. But I see that it’s more color and space and form, almost more akin to abstraction, that becomes the protagonist in your work. Is that something that you’re doing consciously?

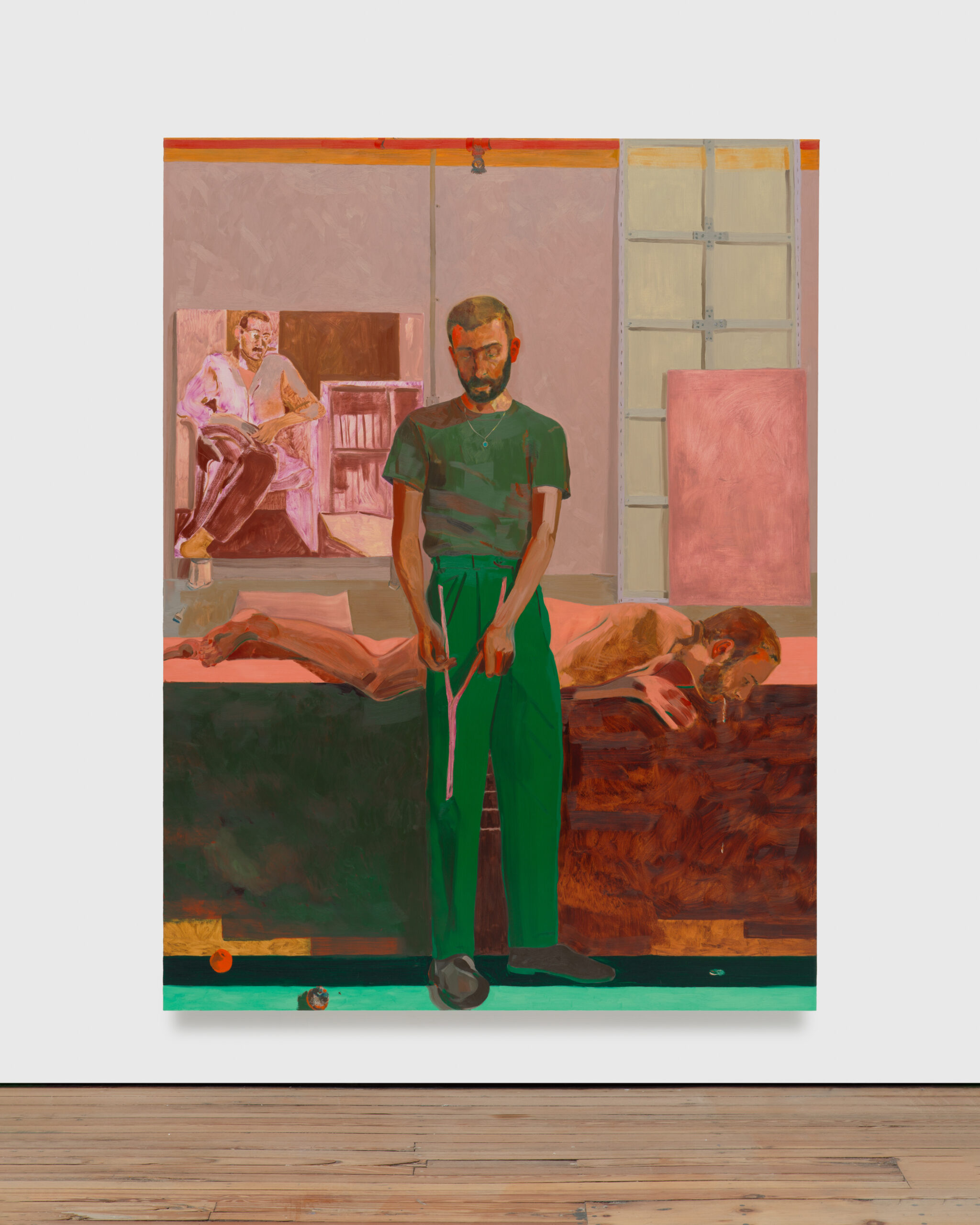

Dowsing (studio), 2024. Oil on linen. 243.8 x 182.9 cm | 96 x 72 in.

CUDAHY: Yeah. Ultimately, I think I’m really interested in paintings with narrative potential. Not in a very strict way, but in the fact that color or texture or composition all have narrative potential. They can either help along an emotion or subvert it and throw a wrench into an easy reading of what’s going on. Sometimes I think about color as additional characters in the painting, and their presences as casting an influence on the figures or the scene. Color has its own presence and sentience, I feel like, in paintings.

ARIAS: Yeah. Also, I see that you have many recurring figures. What draws you back to these people? Are they people in your life? What do they represent?

CUDAHY: So for a long time with my paintings, a big part of my process was collecting images and making iterations of figures or poses that I found. I liked making iterations to play with the idea of archetype. But most of that was from specific archives that I was pulling from. And then as the work became more and more specific to me, the narratives became more involved and complicated. I began to pose people from my own life. Like, my husband Ian is around. Our studios are in the same place. We share a life together. So a lot of the things that I was painting about had to do with him, and he recurred a lot. And then almost as a self-conscious joke, I started to play with self-portraiture. At first, it was very self-aware, citing all of these artist portraits because I’m doing an artist portrait. But then over time, the way that I use myself in the paintings became more fluid as well. Multiplicity is a thing that’s interesting to me about figurative work because I’ve always been agnostic about a painting’s ability to reveal the subject’s true soul or personality. I think it’s more like a painting is a descriptive agent, but it allows you to get one angle or facet of someone at a point in time. So when you have a multiplicity of portraits of someone, across a body of work maybe you get towards what that person is like.

ARIAS: I really like your paintings where you appear sneakily. The classical example is Diego Velázquez in his painting Las Meninas. And I found it quite interesting you inserting yourself into these works almost in the background. It’s very self-referential. Do you find doing that makes it feel more personal? It seems quite vulnerable and expository to place yourself in a painting.

Photo Credit: GC Photography. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | New York | London.

CUDAHY: Yeah. The first time I did it, it felt self-conscious, almost like a reference of a reference. I was making this painting called Blue Room, and it was these two figures in front of this window. And the painting changed 20 times as I worked on it. At one point when I was having a crisis about the painting, I was like, “What am I actually trying to get across here?” The two figures that I was painting were looking straight at the viewer. So I was like, “I think this painting is about being looked at and returning that gaze.” So then I realized, “Then I should put in a mirror and show myself looking and really play that up.” That was one of the first times that I added myself in that way. And then recently, I did a painting in my last show of my husband Ian and our boyfriend Alex, and at the last moment I realized that this painting is about their relationship together, but it’s also about me in this sphere as well. So the last thing that I added was a mirror of me, being the painter in the room. Just like fantasy, because it’s not actually how it was painted in this way.

ARIAS: So earlier, you mentioned how you were sourcing images, and I’ve also read that your process starts with collage. Can you tell me about how you source images?

CUDAHY: Yeah. There’s almost two different modes of working. There’s paintings that happen maybe weeks or months after I take my own photos on my phone from my day-to-day life. I’ll be looking through it and be like, “Oh, that’s a painting.” And then there’s paintings that are more set up in a collage way, and those are sourced from all over. So it could be like other paintings that I’m referring to, or found images, like news images or screenshots, from this archive I’ve been making for the past 15 years.

ARIAS: Oh my god. Where do you keep this archive? Is it a physical archive or do you have it nicely categorized on your computer in all the different folders?

CUDAHY: Not categorized, but it’s just in a heap on the computer. It’s funny because a few years ago, this day job I was working had a Xerox machine that I would exploit. So I was like, “I’m going to print out the thousand images I have here.” So for a little while, I had the physical prints in my studio, and I still do have them. I have a big pile of collages and stuff that I’ve made from those. But when I’m looking for an image, sometimes I feel like it’s so separate from being in the studio and painting. It’s more like I get into this trance and I’m just cycling through images and allowing myself to directionlessly imagine potential ideas. I need that scroll to be able to get into that kind of generative thinking.

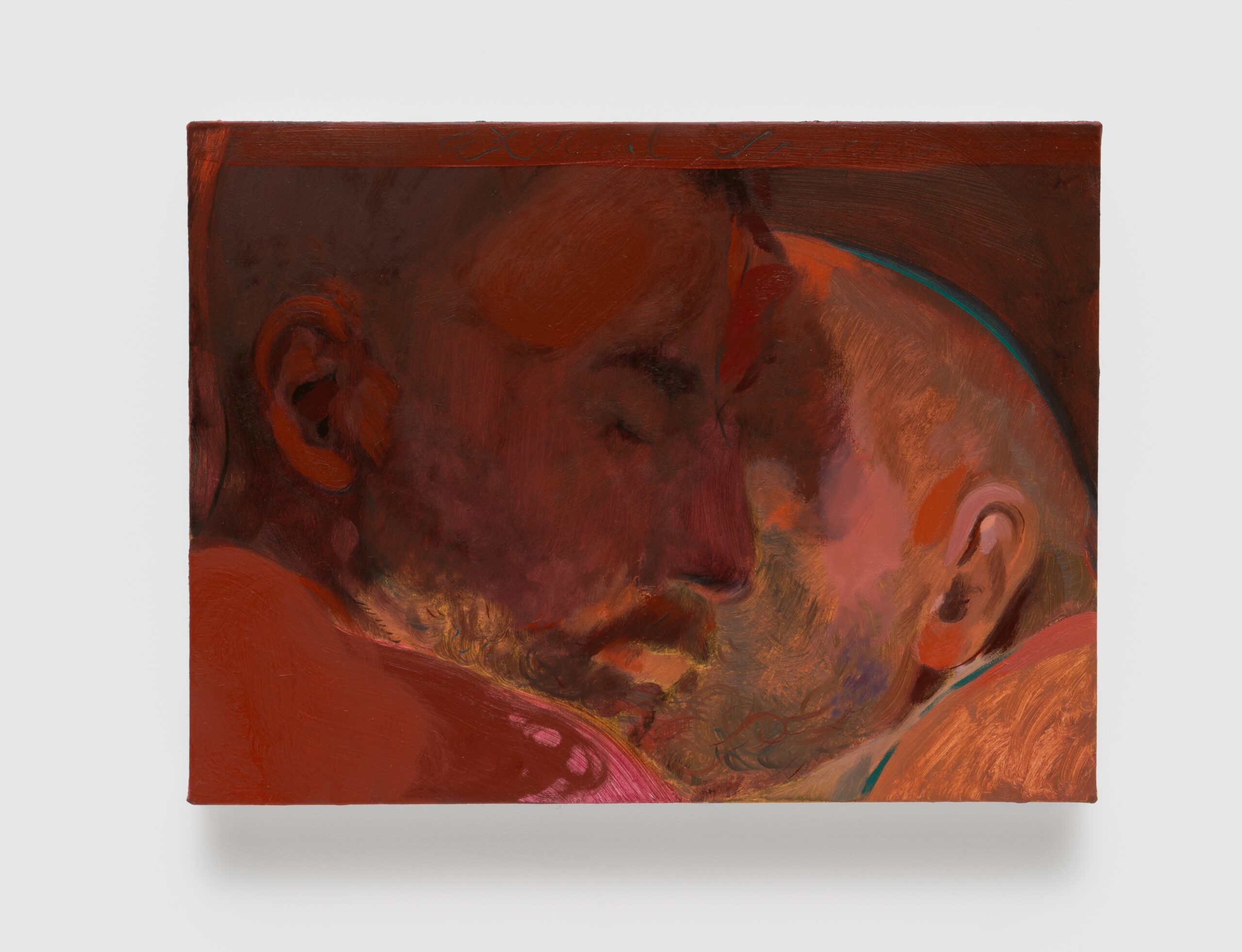

Eternal Lovers, 2024. Oil on linen. 30.5 x 40.6 cm | 12 x 16 in.

ARIAS: What’s your process for building a painting? Are you doing it all in a few sessions, or are you working on something over months, or working on multiple pieces at a time?

CUDAHY: The painting process itself is very fast to get the kinds of saturation and color that I’m interested in. I’ll work on the paintings for months, but a lot of it is like I’ll have a session one day where I paint a ton of it, and then I have other paintings going over the weeks. There’s a lot of moments during the making of a painting that could go in so many different directions. It’s nerve wracking.

ARIAS: You have to be very intentional always. Or you can wipe everything and do it all over again.

CUDAHY: Absolutely. Especially the shows I did in September, I made so many paintings that I cut or got rid of. There’s a lot of editing.

ARIAS: Right. Something I’ve been thinking a lot about and your work has especially made me think about is how memory works in painting. Traditionally, artists fully had to rely on their memory. If they wanted to paint a sheep on a hillside, you couldn’t snap a picture of it and go back to your studio. And then in contrast, today, we are so saturated with digital images. Imagery is such an easy commodity that we have. I think there can be an argument made that this element of memory can be removed. But I think your work is a response to this tension between our digital age and the traditional form of painting. How do you use memory in your work? And how do you balance the convenience of digital imagery, with the depth and nuance that comes from working from memory?

CUDAHY: That’s a really good question because I feel like I have 80 different thoughts about it. On one level, there’s foundational art education. The goal is to really make you present and observe. So for me, even working from found images or collaging things and then painting from it, I’ve always tried to keep that part of the art making that was such a revelation when you first started painting alive. I guess I’m not just using something as a one-to-one. I’m really interested in also the digital flattening that is primarily how we see most images. We basically see most images as flat, almost like stained glass. And because that’s how we see images, I feel like a lot of contemporary painting is very fluorescent, exciting colors, glowing. And then I feel like the way people think about art history [is that when we] moved on to that idea it kills everything before it. The fact that we have flat digital space now doesn’t negate and remove older ways of conceiving or representing space. I think I’m interested in just having a multiplicity of kinds of space.

ARIAS: That’s perfect. And I’ve been thinking a lot about collective memory and the collective queer memory. And traditionally, queer people have not been shown in figurative painting. Is this something that you’re conscious of?

Photo Credit: GC Photography. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | New York | London.

CUDAHY: I mean, in my own personal relationship with art, and I think it is a common queer experience, there’s an element of trying to find these histories that either were very clearly out in the open, but they weren’t commented on or understood, or they were hidden or marginalized or pathologized. So there’s this contemporaneous mapping of the people in your life, and then there’s also this desperate need to find connection with past people that had experiences similar to your own. I always think about that Muñoz essay, “Utopia’s Seating Chart.” And he talks about Ray Johnson and this insane network, a choreographed male network that he made, literally sending male art around. But that could be the framework for thinking about a queer art universe.

ARIAS: It seems a bit like you’re building your own queer world through your paintings.

CUDAHY: Yeah. I definitely think painting and constructing images is a way that I have of consolidating all these things that I’m thinking about, so it is this complicated network. And to a point that you made earlier in our conversation when we were talking about removing rules, I guess I’m interested in there not being any censoring of what can exist in my painted world.

ARIAS: I think that’s really lovely. What kind of stuff are you working on now?

CUDAHY: You’re finding me in a very unique period for me because the past four or five years, I’ve been working like crazy and I haven’t had any sustained breaks. There’s always a show that would happen and then I’d be working on the next project. And then this year, there were a lot of projects that we’ve been working on for years that all came into the world at the same time. So at the moment, I don’t have an immediate next project, so I’ve been making a ton of these little drawings.

ARIAS: Those are lovely.

CUDAHY: The last time that I had a period where I wasn’t painting super regularly in the studio was right when COVID happened because I lost access to my studio for a couple of months. So this is a less traumatic version of that where I just have some time to reflect and think about what I want the next to be. I just have kind of a breather.

ARIAS: Does it make it feel a bit like you’ve made it, that you’re finally in a place where you can take a break without having to stress?

CUDAHY: I definitely stress. But I’m a workaholic. And a lot of amazing things happened in the past few years that I avoided reflecting on by just pushing myself more into the work. I feel a lot of gratitude and then I feel nervous about that. It’s an anxiety cycle. But I’m trying to actually have breathing room and be like, if I take a break, it doesn’t make everything end, which I think is my deep fear.

ARIAS: Definitely not. I mean, art is something that you work on for your whole entire life.

CUDAHY: Yeah.