STUDIO VISIT

How Conversion Therapy Inspired the Artist Leonard Baby’s New Series of Paintings

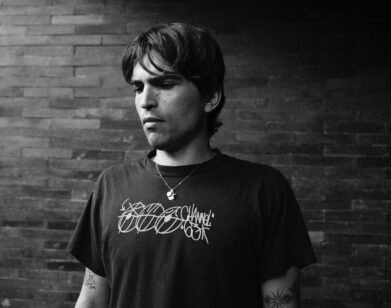

“I would play with dolls with my sisters, and it felt like I was doing hard drugs,” recounts the artist Leonard Baby, whose new solo exhibition at Half Gallery marks an inward turn for a painter best known for depersonalizing his subjects. The show, in which Baby explores family and trauma by depicting film stills, is his most intimate one yet. “It has been heavy, but it’s also been really cathartic,” he told me. Growing up in a restrictive religious environment that taught him to pray away his feminine proclivities, the New York-based artist’s new paintings are a love letter to his sisters. In 8 new acrylic paintings, he delves into the scars sustained from his experiences in conversion therapy and the liberating power of embracing his true identity as a queer artist. Before it opens next week, Baby invited me to his live-in studio in Bushwick to discuss his childhood rebellion, his decision to use a pseudonym, and the inspiration behind his very first self-portrait.

———

LISA BOUDET: I remember last time I was here you were wearing ballet shoes.

LEONARD BABY: I always wear ballet shoes.

BOUDET: How come?

BABY: I don’t know how conscious it was, but I really admired this pair of ballet shoes in Walmart when I was a kid, and I wasn’t allowed to have them. So now that I can buy whatever I want, I buy myself ballet shoes.

BOUDET: Awesome. So we just had a little browse around your studio and I saw you had a saw. What do you use it for?

BABY: For the past few shows I’ve done works on wood panels, and because I painted film stills, I’d have to do custom dimensions. So I would just buy my own wood and then cut it on the spot. It’s way easier than planning out ahead of time and just having to get custom boards.

BOUDET: Where does your passion for movies come from?

BABY: I think it started in high school, when watching films was a form of escapism for me. This was back when Netflix had a subscription by mail, and my parents would order adult rated-R films and I bought myself this little portable DVD player and I would sneak the movies and watch them in the middle of the night. That’s how I got introduced to more of those mid-2000s, independent low-budget films, which then introduced me to the mid-century European stuff that I’m mostly referencing in my paintings. It just exposed me to this world that I didn’t know existed. Then I moved to New York and got a job at a repertory theater.

BOUDET: Were there any specific directors that inspired you?

BABY: Early on in high school, the ones that got me excited were Lars Von Trier and David Lynch, rest in peace, and Wes Anderson, and Sofia Coppola and all those contemporary greats. But of course, they’re referencing these older auteurs. So watching them got me excited to learn who they were inspired by.

BOUDET: Really cool. And you used to work in a movie theater.

BABY: Metrograph.

BOUDET: How was that?

BABY: It was so fun. I thought that that’s what I was going to do for the rest of my life. And then, I got to paint for a living. But I wouldn’t mind if this all fails, I can always go back to the movie theater.

BOUDET: And were you painting back then on the side already?

BABY: Yeah, I was always painting. I just didn’t know anyone would be interested in my work. But I started posting stuff on Instagram and people expressed interest, and it kind of shocked me. I would give the paintings to my friends and family, but when people started reaching out, being like, “How do I buy these?” is when I realized that I could make a living off of it.

BOUDET: So you started to paint on small wooden canvas. Is this what you were doing as well back then?

BABY: Back then, mostly I would just find stuff off of the street. When I was working at the movie theater, the marquee that all of the showtimes would be on were on these wooden blocks that were magnetic, and we would change them out every day. They didn’t magnetize great, so they would fall down and get chipped. And in the storage closet there was a giant stack of ones that were chipped up, and it was kind of ambiguous whether we were going to fix them or what was going to happen with them. So I just took those home slowly and painted on them for a while. Those were still some of my favorite paintings that I did. There was something spiritual about them being on these, like film stills on these movie theater marquee letters.

BOUDET: It’s funny how you ended up using this specific format from working at the movie theater. It definitely has this cinematic feel. But this show is pretty different from the other ones, and it’s much more about your personal life.

BABY: Exactly. This show is about–if we’re speaking about it in film terms, the main characters are my sisters. I have four sisters, and it’s about the trauma that we collectively experienced, and also just the sweet memories that we have. We’re all very close and we were raised pretty conservative and religious. As a closeted queer person growing up, that was a confusing time to navigate, but having four feminine figures my age to go through that with was life-saving and inspiring. They’re my best friends and they really got me through that. So this show is an ode or maybe a thank you to them, or just a meditation on how much they mean to me.

BOUDET: What was it like at home when you were a kid?

BABY: It was pretty restrictive. There were lots of rules. It was oppressive.

BOUDET: What type of rules?

BABY: Rules on what we watched, on what we ate, on what we wore, on who we associated with. We really weren’t allowed to associate with people who weren’t religious or conservative. But being an artistic person and a queer person, I always had this real hunger for something outside of that. And of course that’s when that’s where film came into things and music was really inspiring. But painting was the most inspiring thing for me growing up. I think visual art is really what pulled me out of the grips of that cult, for lack of a better term.

BOUDET: Do you remember breaking rules as a kid, maybe by dressing up a certain way or watching something that your parents didn’t want you to watch?

BABY: The thing that stands out to me the most in terms of breaking rules as a kid was being attracted to feminine things. I would play with dolls with my sisters, and it felt like I was doing hard drugs with them. It felt very much off limits. Or when we dressed up, I would want to wear sparkly things with them. I had a sense that that was really bad to do. So I broke every rule, I did everything wrong, but for whatever reason, that was the most tempting thing for me.

BOUDET: Was it scary when you were breaking this rule? Would your parents catch you dressed up?

BABY: Totally. I’d have to do it secretly for sure. And I was always on edge that I’d hear footsteps coming and I’d have to drop the Barbie doll, and act like I was doing something masculine.

BOUDET: How did your parents react to your attraction to femininity?

BABY: They didn’t like it. They were big on this trend that we’re still seeing today, which is like, “Real men do ABC,” and were very adamant on defining masculinity. That’s very important to conservative people and that was very important to them.

BOUDET: How did that impact you?

BABY: I just felt repressed and like I couldn’t be myself. I wanted to expand so much more than I was able to, but a weird place that I felt like I could mesh the two was in painting, particularly by impressionists. There’s [Vincent] Van Gogh and [Edgar] Degas and [Paul] Gauguin, who are culturally viewed as masculine men, but they’re meditating on these more feminine, beautiful things. From a pretty young age, I had identified that that was a safe space for me to explore these more feminine desires that I had, but in a safely masculine construct.

BOUDET: Was there anything else that maybe your parents did that made you go back into your shell of feeling like you shouldn’t be the person you felt like being?

BABY: When I was in middle school, they sent me to conversion therapy. It was these one-on-one sessions with this guy who claimed that he used to be homosexual and was cured from it. And at the time, I didn’t know that that’s what was going on, but he would tell me that engaging in these culturally understood feminine acts is not what men do. I knew that that message was always sent to me from when I was born to when I was moved out of the house. There was always an attempt to just beat the feminine out of me.

BOUDET: So art was there as a form of escapism, but also your sisters were a strong support system at the time. And even being here and seeing the canvas that you have for your show at Half Gallery, we can see a deep sense of connection with your sisters.

BABY: Yeah, in this show I really wanted to create these main characters that represent these different archetypes. But they’re such unique people, so that was really easy to do. So the painting of my youngest sister Isabel, is a pretty–I don’t know, how would you describe it?

BOUDET: Very Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct.

BABY: Right, exactly right. It’s–

BOUDET: Defiant.

BABY: Defiant, definitely. Like a “fuck you” attitude. And that’s the attitude that she’s always had, and I’ve always looked up to her for it. Like I said, there was so much limitation on us growing up, but she just never seemed to have much respect for that. She would wear whatever she wanted and she would talk however she wanted, and she wasn’t ladylike. So for this painting, I wanted to pull out that attitude. She is posed in an obscure way, and I was looking at a lot of Balthus for these paintings. Of course, there’s controversy that comes with him, but I wanted to explore the male gaze as a queer male gazing upon family. I don’t think that we’ve seen that much.

BOUDET: And you’re also playing around with religious imagery. Maybe you can share how you did that in this painting as well?

BABY: So, over her shoulder is a picture of Lana Del Rey, who I think is one of, if not the most influential icon of my generation and my younger sister’s generation. And she has meant a lot to both of us. It’s the same defiant attitude that I wanted to portray in this painting, that I think Lana really effectively portrays in her work. It’s a messy version of feminism and defiance against the patriarchy, and I think that can look like maybe clinging to the patriarchy in some ways, through Stockholm Syndrome or something. Mine and my sister’s experience with the patriarchy growing up has manifested itself in confusing messy ways, and I wanted to explore that in these paintings.

BOUDET: And talking about patriarchy, this show is about family, yet your dad is absent. What’s your relationship with him?

BABY: It’s currently non-existent, and at the moment I feel good about that.

BOUDET: It’s something we’ve seen this come up in a couple of other shows. Would you say you have daddy issues?

BABY: Definitely. What I mentioned earlier about Stockholm Syndrome, we’re talking a lot about me growing up and the masculinity being beaten out of me. I am still very drawn to classically masculine aesthetics, which is ironic because my whole life I was trying to escape that. But in paintings and in movies, and just in life, I find myself drawn to the traditional idea of masculinity.

BOUDET: Is there anyone from your dad’s side with whom you’re still in touch?

BABY: I’m really close to my dad’s brother, who’s actually a painter. He’s kind of come in as a surrogate father figure. He’s been super supportive and he really helped me come to terms with my sexuality. He’s always gone by a pseudonym, and he encouraged me to go by a pseudonym. And at first I was pretty resistant to that, but once I did it, I realized that it was like that Shakespearean trope that you can be more authentically yourself when you’re wearing a mask.

BOUDET: So it helped you in your art, and did it help you as much as well in your personal life to be Leonard Baby?

BABY: Definitely. I would say it helped me come out more authentically as a queer person, but it for sure helped me be more honest in my work, because I could blame the honesty on Leonard Baby. Leonard Baby was kind of a scapegoat at first, but now I feel like I’ve just grown into him.

BOUDET: I can see here there’s this painting with a cute naked man lying in the bed. Who is this?

BABY: That’s my boyfriend. That was a really fun one to paint. It’s the first male nude that I’ve done. I didn’t plan for it to be in the show. It was just kind of a way for me to stay excited while I was painting my sisters.

BOUDET: So it’s your first naked painting. Are there any other pieces in the show that are something that you’ve been experimenting for the first time as well?

BABY: There’s faces in this show and pretty much all of my other paintings, but I intentionally crop out the faces. But this is a portrait show, and I haven’t done that before. There will be a self-portrait, which is new for me.

BOUDET: Can you tell us more about that?

BABY: The self-portrait is going to be modeled after the Lucretia paintings, which is the story of this woman who is accused of sleeping with another man and because of that, she kills herself. It’s this really dramatic, suicidal composition. Because the show centers around growing up closeted, going to conversion therapy, queer oppression, I wanted to talk about when someone’s not able to be themselves. The painting is about, “If I can’t live the way that I want to live, then I don’t want to live at all.” But I also want to be careful about how I talk about suicide.

BOUDET: I think it’s the message around freedom. Like Patrick Henry used to say, “Give me liberty or give me death!” It’s about standing up for oneself.

BABY: Absolutely. Growing up I really had a sense of hopelessness and at many times wanted to give up. And I don’t feel that way anymore, because I’m living the way that I want to live and living authentically. But this painting is a meditation on those feelings of not feeling free, and the Lucretia archetype was an interesting way to explore that.

BOUDET: I think it resonates even more in today’s context, with the current President. Everyone is scared for their freedoms.

BABY: Absolutely. It’s strange, because you’d think that the time period we’re talking about here is 15 years ago, and you think with time things get better. I think for a while they were, but here we are again.

BOUDET: Was there a piece that you dreaded making for this show?

BABY: Kind of all of them. I was nervous to be living with this content for so long. It has been heavy, but it’s also been really cathartic. This painting I’m working on now, which is my twin sister, has been a heavy piece to live with and converse with every day. We were pretty inseparable growing up and as we’ve gotten older, we’ve naturally grown apart, and that’s been really difficult. It’s been a hard pill to swallow, growing up and becoming a more individual person is pretty heartbreaking to me. But that’s life, and I’ve been working that out with this painting.