NUDE

How a New Portfolio of Lost Paul Cadmus Drawings Is Redefining His Legacy

Paul Cadmus, photographed by Bruce Weber.

Paul Cadmus, a trailblazer of 20th century American art, is celebrated for his provocative portrayals of city life. His paintings and drawings detailed urbanites “carousing in queer postures,” that is: slouching, leaning, or draping arms around one another in the locker room; bending, spinning, and twisting legs in angles that look impossible to hold for long all the while lollygagging along New York City’s piers. His gathering of sailors, floosies, performers, street loiterers, and beach bums are rendered with exaggerated precision and comedic undertones. They frolic in stage-like compositions. All of which is to say, everyone in a Cadmus is trying to drag someone to bed. In Paul Cadmus: 49 Drawings, a new portfolio of the artist’s work published last month by Phaidon, the dragging has been successful. The book compiles a confidential, affectionate collection of drawings devoted to his long-time lover and muse, Jon Anderson. It’s a whole thick book of hand drawn Anderson nudes.

Spearheaded by art dealer Graham Steele, with a contributing text by Meyer, the art critic and curator Jarrett Earnest, and the painters Nash Glynn, Oscar yi Hou, and Doron Langberg, this portfolio underscores Cadmus’s meticulous draftsmanship while revealing an emotional connection to Anderson. In fact, the drawings were found stashed away in one of Anderson’s dressers long after Cadmus’ passing. “With these [drawings], you’re admiring the way that the white chalk is burnished into a testicle,” he told me. “These were not drawings about money. Nor were they ever to be sold or seen. The concept of being pornographic was abhorrent to him.” Instead, the collection captures the “alchemy of desire and domesticity,” transforming classical techniques like observational drawing into a timeless celebration of both human form and fleshy function. What makes this collection particularly compelling is the tension between its technical brilliance and its deeply private nature. These drawings, many of which were rendered on treated papers, existed as a shared dialogue between Cadmus and Anderson. “These works are like a love letter, written in pencil, to the person who gave him the freedom to create without pretense,” added Earnest. “It’s about being right there with this dick, tracing it in real time.”

Through this lens, Paul Cadmus: 49 Drawings redefines Cadmus’s legacy. The collection not only immortalizes Anderson, whose dancer training allowed him to hold poses for long periods, but also traces the evolution of their relationship over three decades. This intimacy bridges the physical and profound in a way photography simply cannot, offering a rare glimpse into Cadmus’s interior world—a world where art, love, and touch were inseparable. This is all a very lovely thing: his drawings, just like his paintings, invites prolonged viewing, disproving the old adage that painters don’t make for compelling subjects (“nobody wants to watch a movie about paint drying…”). To the contrary, the best of them possess the skill of an expert draftsman, showcasing an obsessive attention to detail and a flair for the dramatic in their rendering of facts and feelings. The life of Paul Cadmus would, in fact, make for great cinema. Luca Guadagnino, I’m looking at you.

———

JARRETT EARNEST: So are you still deep in trying to help the Cadmus world?

GRAHAM STEELE: Yeah, we’re still trying to figure out the whole thing about the images and this lack of an estate. Someone or something, I don’t know if it’s Casper the Friendly Ghost, has inherited the rights. There are rights to Cadmus’s name and likeness and reproduction but there’s just no––

EARNEST: Right, it goes through ARS.

STEELE: You have to register with ARS. It’s this whole crazy thing.

EARNEST: When we did The Young and Evil, we paid Cadmus rights through ARS.

STEELE: Right, but he was alive.

EARNEST: No, he wasn’t.

JOHN BELKNAP: When did he pass away?

STEELE: He passed away right after you guys did the book.

BELKNAP: Is there drama? Or what’s the deal?

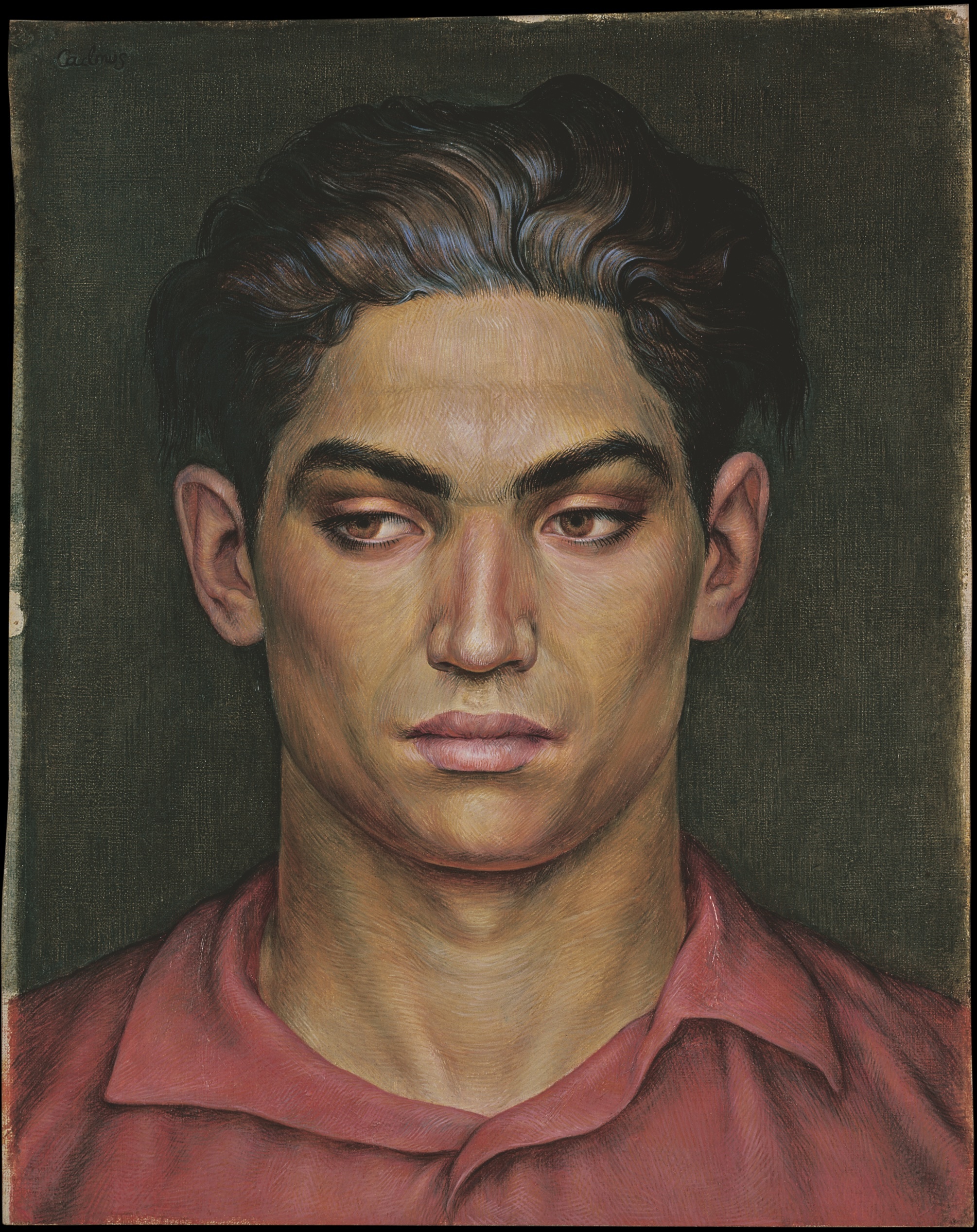

Francisco, 1933 and 1940.

STEELE: Drama would be festive. It’s more like, we contacted the lawyer who happened to live next to Jonathan Anderson, and they were like, “We don’t want to know.” That’s why these things got dumped at auction because Jonathan Anderson had a cousin or something. Someone got money. There were trustees of the will. The sad thing about the will is that the only thing we know from a couple of the people who knew Cadmus well was that there were mostly gay charities that Cadmus wanted in the absence of children. Now, whether that was honored or not…

BELKNAP: Because he was active throughout his life with gay charity.

STEELE: Yes, and especially more during the AIDS crisis. He very quietly would provide drawings to auctions and these kinds of things.

BELKNAP: For the record, Jonathan Anderson is Paul Cadmus’ lover.

STEELE: Last lover, exactly. And the subject of our book.

BELKNAP: Not the fashion designer.

EARNEST: No, god.

BELKNAP: Did he design any fashion?

STEELE: No.

BELKNAP: He mostly took off his clothes.

STEELE: Exactly. He was a dancer and singer. But apparently there were some saucy Cabaret nights in Connecticut that he was the star of.

BELKNAP: That’s kind of fun.

STEELE: But they met in New York. He was at least two-and-a-half decades younger than Cadmus. And Cadmus immediately loved him because of his dancer’s training. He could keep poses for a really long time.

BELKNAP: Oh, I see.

STEELE: So they worked incredibly well together. There’s an amazing, very long interview with Cadmus from the ’80s with the American Art Archive. His hope was that all of his letters and all of these things would go there, and some of them did. It’s unclear as to what happened with a lot of the paperwork in the house. Jarrett, you can talk about the house you went to, and the state of it.

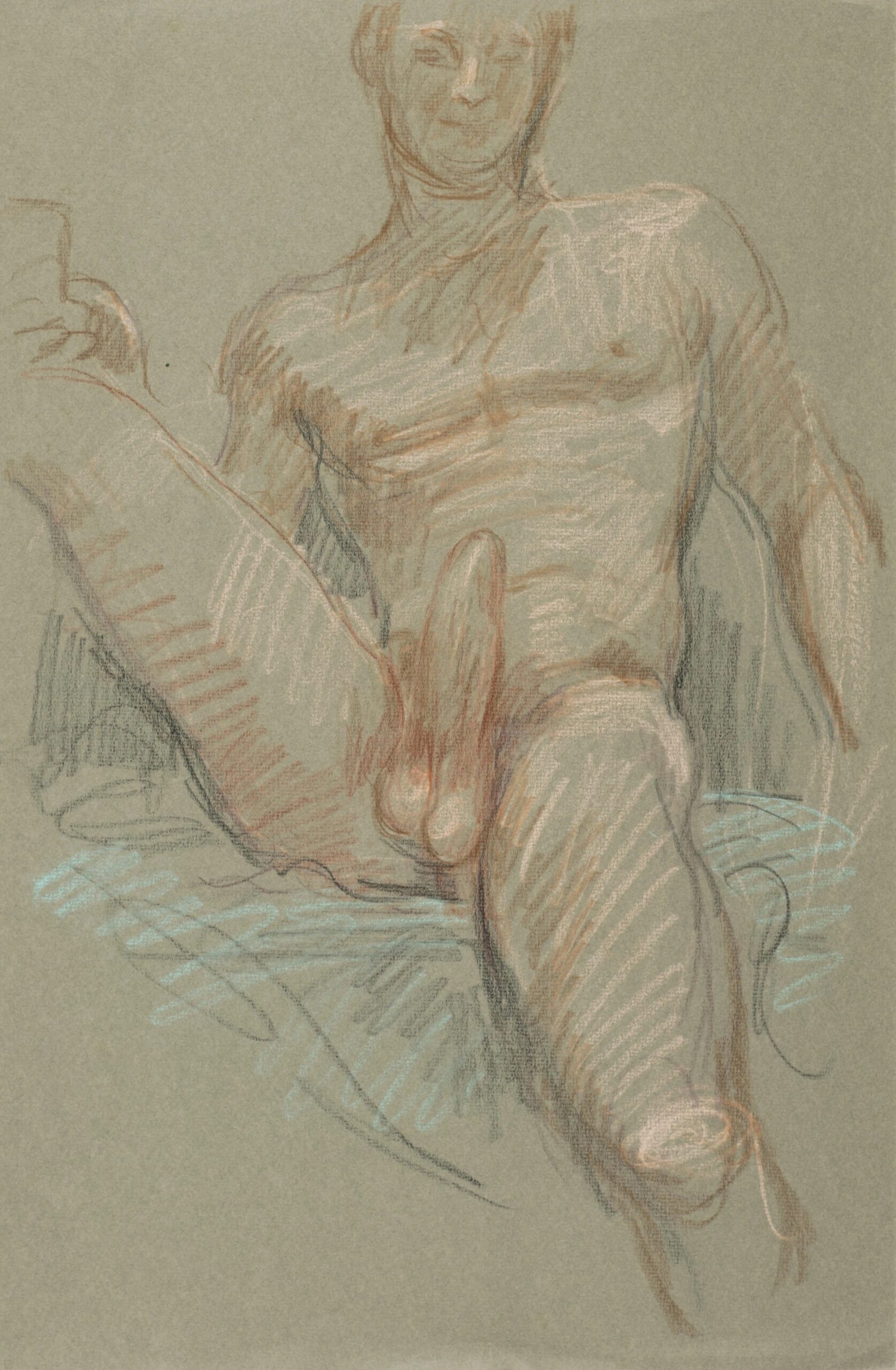

Male Nude, Erect, n.d.

EARNEST: But I thought that all is now at Beinecke at Yale. That’s my understanding. No? You would know.

STEELE: No, no, you would know better. But that’s why this book exists. He bookended the 20th century and so much about queer and gay visibility that what we talk about was really him in the 1930s putting a gay man, a transgender individual in public for people to see. And while you see it at the Whitney, there’s no books in print on Cadmus.

EARNEST: But you found Cadmus through a book at a library, right?

STEELE: I found Cadmus through… are we talking about when I was a tiny gay human?

EARNEST: In fact.

STEELE: Yes, I found Cadmus because that first painting Factory Worker: Francisco is at Dartmouth. A lot of these things that were spread out into small museums around America, given by someone, shall we say, a gentleman who very much appreciated the company of other gentlemen.

EARNEST: I’d say a gentleman of quality.

STEELE: A gentleman of quality, a grade-A fella.

BELKNAP: I have some kind of annoying questions.

EARNEST: Great, let’s do it.

BELKNAP: We want to talk a little bit about pornography, but maybe we can expand that to thinking of this image a little bit. The thing that’s interesting to me is, there’s this thing that happens with Paul Cadmus and also some other artists where they get described as “old master-ish,” which doesn’t necessarily mean anything very tangibly other than it’s technically skilled, and they’re thinking of art history in particular ways. And I think part of the performance of skill and material investment, in some ways, disguises this very, very intense erotic impulse in the work. That is what is so incredible about this work, it foregrounds how much he wants to spend time making drawings of his boyfriend’s dick and asshole. So rather than talking about it as an old master, I’m more interested in thinking of it as a relationship to obsessive outsider pornographers who make the work that turns them on, where the eroticism lies in actually making it. It’s not something you’re doing for money.

Male Nude in Dynamic Pose, c. 1970s.

STEELE: Nor were they ever to be sold or seen. I totally agree. But what’s so interesting is that the concept of being pornographic was abhorrent to him. So you’ll notice that most of these dicks are at rest. They are “old mastery” because they’re on treated papers. They’re with crayon that dissolves into the page. They are rendered beautifully and traditionally, and the body in pieces as we know it from ancient statuary, the cloak that you get to hide under when you are emulating or working in the tradition of art history doesn’t make it any less pornographic. But this is not just something that was this obsession for a period of time, this is over the entire course of his life with John.

BELKNAP: I’m thinking about Warhol’s line drawings that are slightly pornographic, those are almost more pornographic.

STEELE: Yes, there’s a crudeness to them in every sense of the word.

BELKNAP: Do you think that’s because those were put in a market context, or because Warhol is now thought of as pop art/commercial?

STEELE: When I use the word crude, it starts with the drawing itself. Warhol’s line was far from masterful. So there is something about a hustler leaning back and he uses all of these tropes, but on the basic level, it’s the actual line itself. With these you’re admiring the way that the white chalk is burnished into a testicle in a way. With Warhol, you’re just like, “Well, that’s a guy leaning against the wall with a dick out.”

EARNEST: You’ve waited your whole life to say “White chalk burnished into a testicle,” and I’m so glad we finally could get it on record.

CHALK ON GREEN LAID PAPER, 111/8 × 16 IN. (28.3 × 40.6 CM).

STEELE: Honestly, I can die happy. You’re welcome.

EARNEST: For me, one of the reasons that drawing is so special is that it has this very alive and charged relationship between the act of its own making, the way it discloses the act of its own making in the present tense, and it is about the interface between the eye and the hand. It’s about him being right there with this dick. And it isn’t a fully resolved drawing in the sense that there’s all this stuff in which it’s only barely indicated. It’s like, that’s part of where it shows you what he cares about, and what he’s looking at in real-time. And in that sense, the eroticism is in the act of drawing itself.

STEELE: You’ve made me think about a painting of Sandy Campbell, who was briefly his lover during the war years. When I got that picture, it said it was four-and-a-quarter by four-and-a-quarter inches, it was framed like a drawing. I took the matting off and discovered that he had gessoed an uneven board, but it extends out in these beautiful lines that are drawn. The egg temper process uses a very fine brush that is pencil-like. So again, he’s bringing your attention to what he wants to show you, and he has this idea of the crop or the cut or the decisions that he’s making in terms of the composition. Everything is very intentional where it starts in the locus of the groin, and once he has confirmed that specific images finality, it’s done. And the immediacy of those drawings, it’s the feeling of them you can experience immediately. Even in reproductions, although the reproductions are fabulous–

EARNEST: The reproductions are fabulous.

STEELE: Exactly. The quality, stock of this book is amazing.

EARNEST: Really went the extra mile.

STEELE: Those Kinsey images are insane.

BELKNAP: That was crazy. How many of those did he do?

STEELE: Well, they’re all with Kinsey. Have you ever gone?

EARNEST: Yeah, of course. They were all in The Young and Evil.

STEELE: But they’re not all of them.

EARNEST: No, I went out there and I went through the drawings and I made a selection.

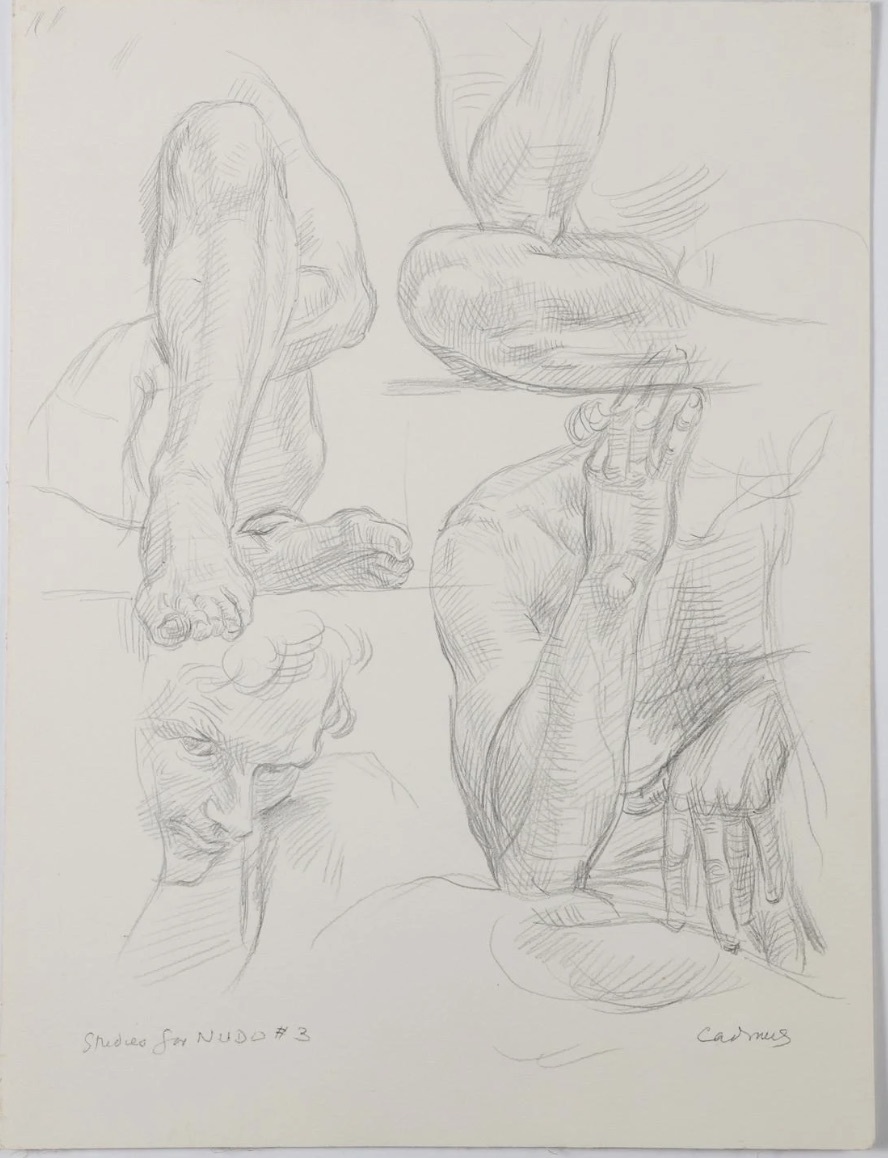

Studies for NUDO #3, 1984.

STEELE: It was funny because those pictures were all obviously never seen, but there are times where we all bring up the specter of Tom of Finland, who is a very, very different artist, and the motivations and the point of those pictures were very different than the way that Cadmus saw himself. But as Richard said, in comparison to Tom of Finland, when it was just about actual fucking, there was something in Cadmus’s either gaze or hand that never rendered them as sexually. It is still sort of an academician looking at trying to have these writhing, sweaty bodies somehow be rendered in a traditional manner.

EARNEST: You know what I figured out about some of these drawings is that they are based on porn photographs. Later, after I had done The Young and Evil, I found images that were the exact image that he drew for some of them. So I actually think that there is a huge difference between emotionally, artistically. I almost think he made these as exercises for Kinsey.

STEELE: I always wondered, because the lore was that he would go and do sketches and do drawings at the sex parties that George Platt Lyons had organized for Kinsey, because Cadmus always loved drawing from life, no?

EARNEST: I’m sure it was a mix, but I think that the spark of these are about drawings from observation. There’s one drawing that was in the catalog that’s like a self-suck drawing. And I found the image, it’s the exact photograph that he used, and then I was like, “Oh, okay.”

BELKNAP: Self-suck was Cadmus?

EARNEST: Yeah. I can send you a picture. That’s another way that the porn thing comes in, but also early Tom of Finland, when he was doing them because his own sexual interests are different from the works he made as commissions later on when he was a brand. There’s something different when you’re making work of your own because it’s your turn on that makes it. You can always look at an artwork and tell that something is not quite plugged into the electrical outlet.

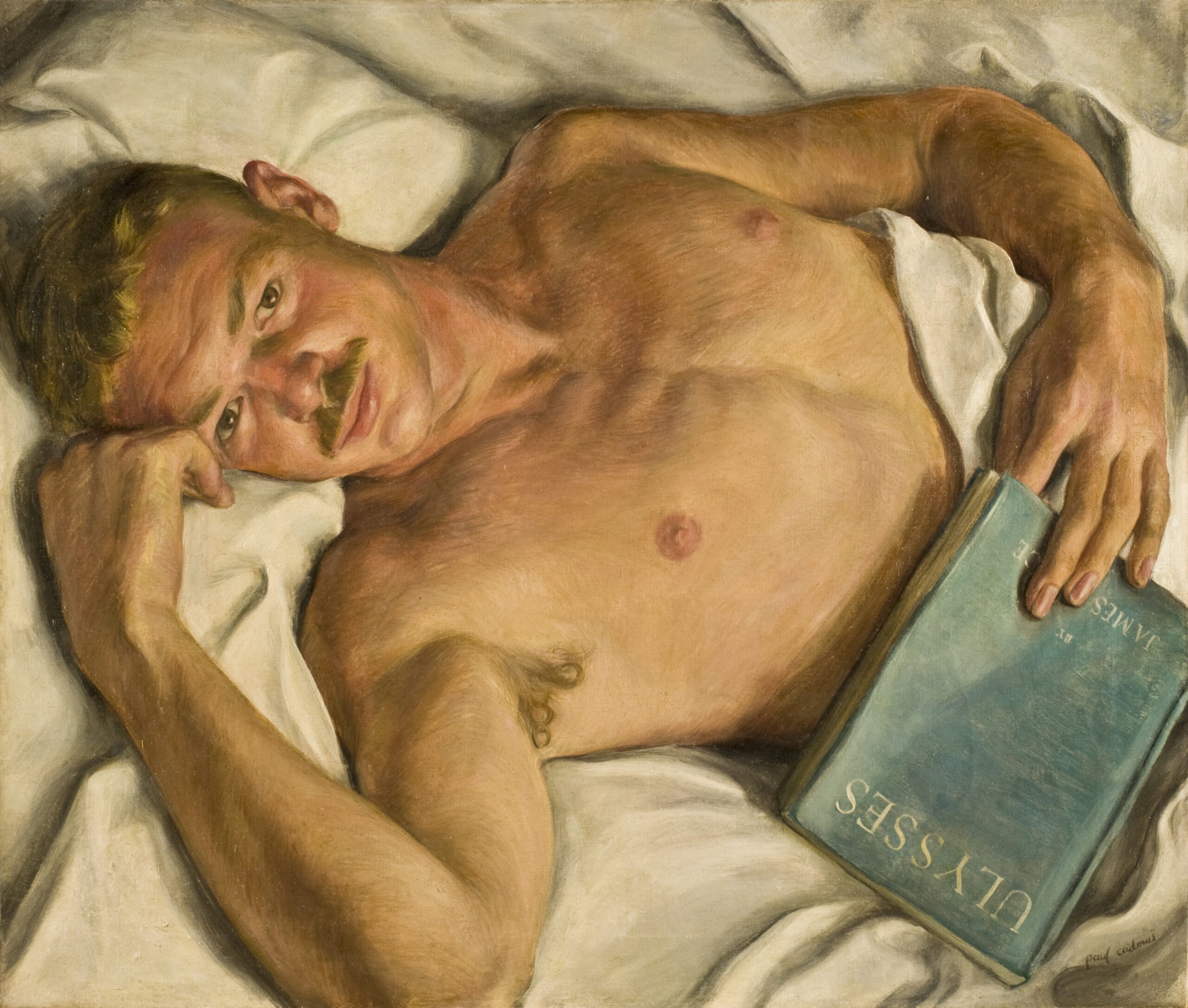

The Shower, 1943.

STEELE: And Tom, sometimes he would have models that he would sketch, but the scenes that we love so much were entirely from his imagination.

EARNEST: Also, I just wanted to say that Anderson was an extremely charismatic and kind man, and you get that he’s this extrovert, but also clearly loved supporting Paul Cadmus. I think the modeling was a way for them to spend time together. So it’s like a chicken and the egg. Are you doing that because you want to paint the subject, or does the subject just want to model for you? It’s not exactly what I intended to say, but meeting him as an older man, the thing is there’s an aspect of this stuff, which is sort of memento mori where it’s being with him and looking at these drawings of his dick in his house that was falling apart and being like, “Wow, your dick is beautiful,” and he was just like, “Thanks.”

BELKNAP: Well also, Graham, I think you talked about this in the book, you had this thing about the alchemy of desire and domesticity.

EARNEST: Yeah, it really is about domesticity. That’s such a nice point.

STEELE: Totally. And there was a familiarity. There were certain pieces of furniture from that house that we all know, there’s the couch that he lays on, and there’s a certain point where Paul says, “I had to switch some stuff up at a certain point,” where all of a sudden had super straight hair or curly hair or would change facial features. So for the last 30 years of his life, was almost exclusively the model that he used. So John’s body we get to see aging over 30 years, and then he died in 1995. There’s pieces in that book that are from 1994 and the hand gets looser. So you see Cadmus aging too. But you see the artist and the model become so known with each other that the looseness doesn’t matter. It’s still suggesting exactly that same energy and exactly that same person.

BELKNAP: That continuity feels really nice. I guess that is a definition of the muse, right?

EARNEST: Well, speaking of muse, it obviously was a complex relationship too. I think the image of him where he paints Anderson as David and his head being Goliath cut off by the pallet, he’s drawing himself in the mirror. That’s pretty intense. There’s this power shift.

STEELE: There are also studies for that picture. Those were scattered all over the place at auction, but there must have been at least 50 different studies of that picture from the most bare bones sketches through to pretty finished drawings.

BELKNAP: So much of the stuff was auctioned off. It was during the pandemic?

STEELE: It was literally April 10th. It was literally advertised to me in the way that the algorithm of Instagram would show me a hot body builder in Nicaragua.

Study for “Male Nude #NM5,” c. 1965.

EARNEST: What I was thinking was, there’s something about having to make work that’s vulnerable and reveals something about yourself that you don’t necessarily want to reveal that makes you uncomfortable. The thing is, Paul Cadmus had a complicated relationship to being publicly identified as a gay artist, and that’s a lot of what this book is about. He was gay in a way that wasn’t problematic for himself, which is part of what’s radical about the work, but he didn’t want to be a gay artist. So putting a work out this, it’s like, “Oh, you’re not just a gay artist, but you’re a cock sucking faggot artist.” And I think that maybe the obsession thing is about willing to do something that’s really scary, really vulnerable, and we don’t really live in a moment where there’s a lot of lip service paid to that without a lot of actual risk, I feel.

STEELE: Can I also just say something that’s interesting from this idea of radicality and the market perspective to bring Louis and Cadmus in?

BELKNAP: Yes.

STEELE: What I thought was tragic about Cadmus’ market is that the most expensive painting is $2.6 million, and I’m thrilled that there’s a Cadmus that’s been sold for that.

BELKNAP: I didn’t realize that.

STEELE: But what makes me sad is that it was probably the most hetero-flexible, literally. It was the portrait of Glenn Westcott’s sister-in-law where they used to stay at the farm in Pennsylvania.

EARNEST: Barbara Westcott.

STEELE: Barbara Westcott, and she’s blonde and American, and there’s a big cow behind her and there’s a hot farmer. And it’s a big picture, about maybe three feet by four feet, which for Cadmus was enormous. It was purchased by an institution, and it’s great that it’s going to go there. However, I would love to see one of the naked men go for this. Lou Fratino just had a painting that sold for $325,000 or whatever at Sotheby’s the other night, and it is a portrait of flowers, and it’s like, this is one of the queer art market stars of the moment. My favorite painting of his last show was the beautifully, delicately, sexily, but gorgeous picture of rimming–

BELKNAP: The last show was incredible.

Jerry, 1931.

STEELE: I would’ve loved to see a picture of rimming open a Sotheby’s evening sale and sell for $500,000. To me, that’s the radicality. But the market doesn’t necessarily know what to do with that. And I understand why. Not everyone can have people rimming in their living room. I don’t know any of those people, but I’m sure they exist.

BELKNAP: I don’t know anyone who’d think that they couldn’t pull that off.

STEELE: You literally don’t. That’s a bunch of bullshit.

BELKNAP: Fine. I want to live with a big, beautiful dick.

STEELE: I live with many, many beautiful ones that I had for a long time in my living room until the collection outgrew it that’s in my office now.

BELKNAP: Anything to say about…

EARNEST: About what? I don’t know anything about money.

BELKNAP: Okay.

EARNEST: I’m just a simple country girl. No, it’s not the way that I talk about art so I don’t know.

STEELE: I bring it up in the way that I wear multiple hats. My interest in Cadmus is as someone who is as that little boy in Vermont looking at that picture, and as the art professional who looks at markets, who looks at legacy, and who understands that there is a difference between price and value, and hopefully those two things can come together at some point. Every night before I go to bed, I pray people with taste will get money.

BELKNAP: That’s a great way to end.

EARNEST: Fantastic.

STEELE: I think we’re geniuses.