Hernan Bas Sees Evil

In an age of Twilight and True Blood, the devil is something we know, and very often, want to sleep with. In his solo exhibition at Lehmann Maupin, “Occult Contemporary”—a name that riffs off the softcore musical genre “Adult Contemporary”—artist Hernan Bas attempts to rescue the devil from the candy-coated world of Hollywood blockbusters, and imbue him with his uncanny ability to terrify ordinary humans. Using old folklore as a source for his visual representations, Bas creates monumental psychedelic dreamscapes—the smallest canvases are 6′ x 7’—that look like illustrations for a 16th century German fairy tale set in a post-apocalyptic world. In such settings, the devil is allowed to be supernatural rather than quotidian, freed from the muck of a banal human existence. “The landscape was as magical as I wanted it to be,” Bas explained. “There were no rules. What emerged was accidental.”

Bas first became interested in the occult in his childhood in upstate Florida. In the woods surrounding their house, he spent a lot of time with his older sister and brother, whom he describes as “junior occultists,” playing ghosts and spirits. “It was a very X-Files type of upbringing,” he noted. Later in life, this interest focused on the devil, the Christian manifestation of the supernatural, whom is an opposing or malevolent entity to God, but not necessarily to man. To derive inspiration, Bas read Baudelaire, who conceived of the anti-Christ as a beautiful dandy; looked at the woodcuts by Gustave Doré for Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, in which the devil appears as a winged hero; and listened to “The Devils Trill” by Giuseppe Tartini, a score “composed” by the devil to forever torture a human composer, who could never replicate it, not even on his death bed. “The devil is always the protagonist in these stories,” Bas explained. “He’s not necessarily a bad guy. He’s just trying to do his job as a professional to influence human destiny.”

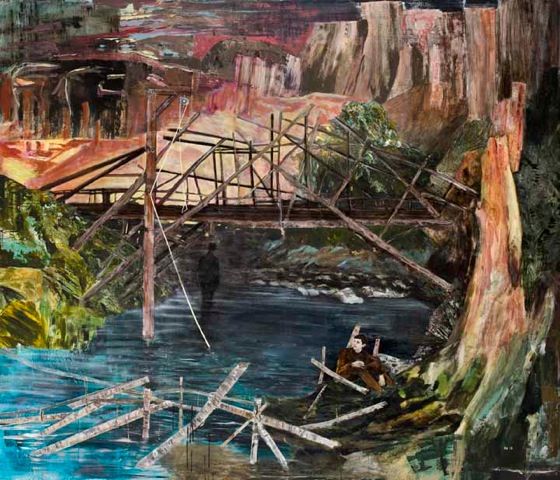

All of these sources come together in “Occult Contemporary,” where the devil is depicted not as some monster from the depths of hell, but rather as a mirror of man himself. In Bridge (2012), the devil is a shadow wearing a top hat, a film noir cut figure that clearly spooks the man at the forefront of the painting, who half turns as if he senses the presence of the underworld. In Devil’s Trill (2012), directly inspired by the Tartini score, two twins occupy a landscape of fallen trees—in the foreground, one is hunched over in despair, in the background, the other, the devil, plays a violin with reckless abandon. In One Of Us (2012), a loosely rendered, Cezanne-esque landscape contains a lone contemplative figure being comforted by a gray shadow, while a group of identical gray shadows observe from a distance. In the composition, it is unclear who is the devil, and who is man. In groups, they are indistinguishable. “He’s a sympathetic character,” Bas said of his effete, slender renderings of evil.

In the exhibition, Bas seems to make the argument that even in the rational age, where we no longer need the occult to explain natural phenomena—at least not usually—there’s still a capacity for the unknown. In the shadows of our dreams lurks a figure that is similar to us, but more powerful, whose job it is to steal our souls, and in doing so, opening up worlds beyond our wildest fantasies.

OCCULT CONTEMPORARY OPENS THURSDAY, MARCH 15TH AT LEHMANN MAUPIN IN NEW YORK.