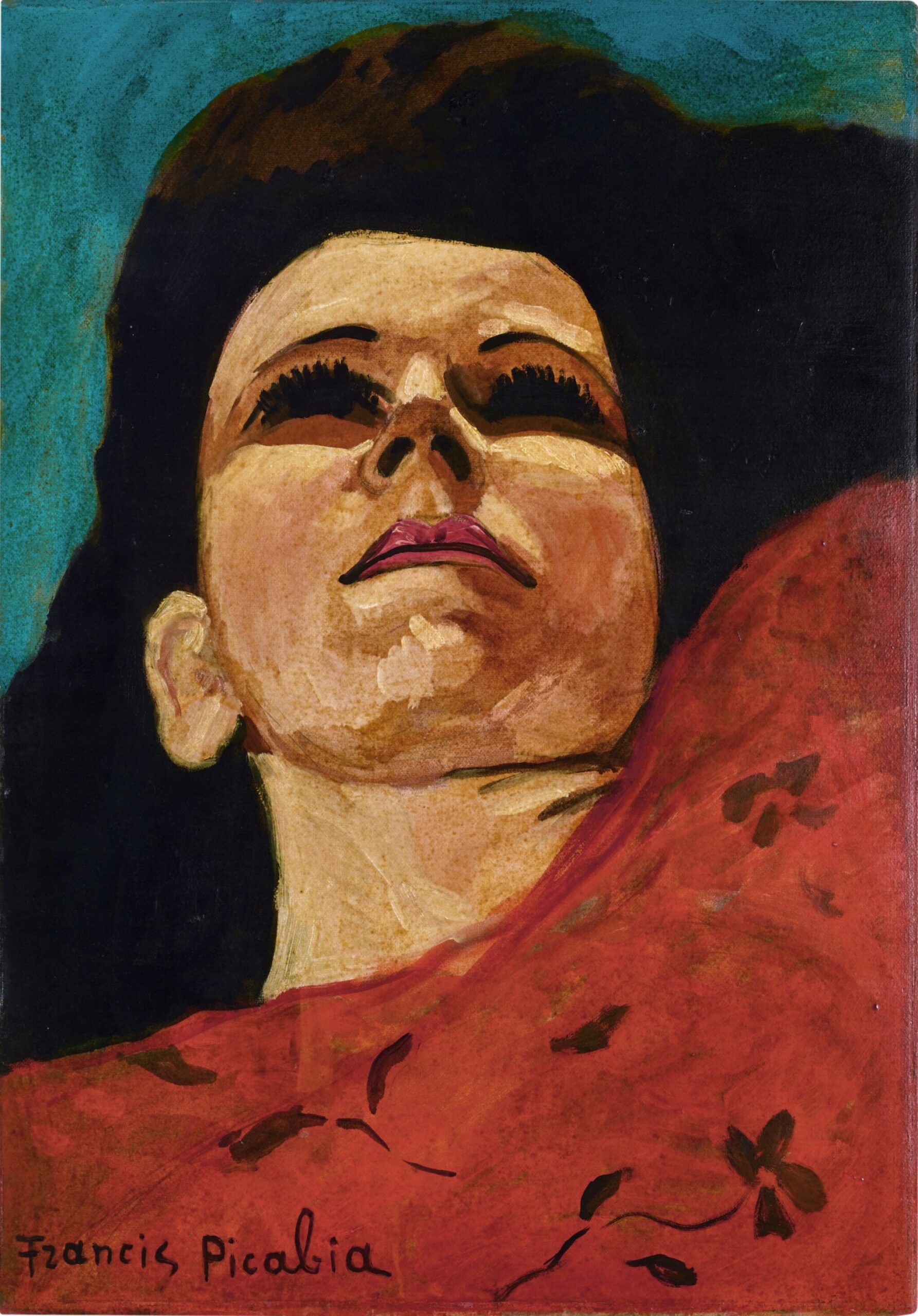

PICABIA

“I Don’t Believe in Meaning”: Getting Existential With the Painter Harold Ancart

Harold Ancart, photographed by Emily Sandstrom. Painting: Untitled, 2024. Oilstick and pencil on canvas. 81.3 x 99.1 cm. 32 x 39 in.

“The head was round so that our thoughts could change direction,” says Harold Ancart, reciting the words of Francis Picabia just before the opening of his show 7 Paintings and 1 Painting. “He’s the perfect example of a painter who constantly changed directions, and it didn’t matter to him to justify how or why.” Ancart, the 40-year old Belgian artist known for his own twists in both subject matter and form, see’s a great deal of himself in the French painter, whose work he’s curated alongside an original painting of his own in a new show at Fleiss-Vallois. In Belgium years ago, he landed in art school “out of desperation,” as he puts it, though he was wary of becoming the kind of artist who “rolls cigarettes and drinks shitty red wine.” Ancart’s journey to esteemed representation was relatively fast, though, and he remembers in vivid detail the humbling experience of arriving in New York and knocking on Richard Serra’s studio door pleading for work. Circumstances had changed dramatically when he and I met in the gallery last month. Ancart, pacing back and forth and bursting at the seams with energy and ideas, was ready to talk about his favorite philosophers, recurring dreams, and all things Picabia.

———

HAROLD ANCART: When I go to a restaurant, I don’t like when there’s too many things on the menu because it’s very difficult for me to make a decision. It’s easier when you have to play the cards you’re being dealt.

EMILY SANDSTROM: Right.

ANCART: So I said, “Well then can I do a [Francis] Picabia show?” He very famously said, “The head was round so that our thoughts could change direction.” He’s the perfect example of a painter who constantly changed directions and it didn’t matter to him to justify how or why he was doing certain things. All of this brings a great sense of freedom to me. And I said, “Well, perhaps I can add one painting that goes with this idea that whenever you are dreaming, elements that have absolutely nothing to do with each other can juxtapose or follow each other, because the dream is not framed by a bigger dream.” But that would be logic or reason or academic thinking. I’m not a scientist. I went to art school.

SANDSTROM: I read that you briefly wanted to be a diplomat.

ANCART: I would’ve liked to be a diplomat.

SANDSTROM: Do you think you would have been good at it?

ANCART: No, I don’t think so. Actually, the reason I wanted to be a diplomat was because you get a diplomatic license plate. You don’t get speeding tickets and you can park wherever you want.

SANDSTROM: And you get the passport.

ANCART: Exactly. You don’t wait in line at the airport, you can smuggle whatever the fuck you want to wherever you want. You live in a big house, you have people cleaning after you, and maybe go to nice dinners and stuff like that.

SANDSTROM: So you wanted to be rich and famous?

ANCART: I didn’t want to be famous. But rich, yes. I certainly didn’t want to be poor. That’s why I didn’t want to be a painter. I was terrified of the bohemian lifestyle that surrounds the idea of the young artist–someone who rolls cigarettes and drinks shitty red wine and stuff like that.

SANDSTROM: I see.

ANCART: But turns out, if you want to be a diplomat you have to study a lot, which I was never good at. All I would do is doodle or draw in school to pass the time. I guess you may experience this when you write or something, you open this window and then you get into this world and time vanishes. I call it “the zone,” and once you enter it the world could collapse around you and it wouldn’t bother you. It’s a place that I always loved.

Francis Picabia. Les Martigues, 1899. Signé, daté et titré en bas à droite. Huile sur toile. 30 x 40,5 cm.

SANDSTROM: Well, there’s a lot I want to talk about with the show and your contribution to it, but I was reading that story about you and Richard Serra where you–

ANCART: Should we sit down on this?

SANDSTROM: Yeah, let’s sit down.

ANCART: No, let’s lean. I feel like leaning.

SANDSTROM: Okay, we’re leaning now. What was it like for you to first have your art recognized commercially?

ANCART: Well, the truth is that I ended up in art school out of complete desperation. I was good at drawing and good at roller skating. But at 20 years old, there were no real prospects for me to become a professional roller skater. So I went to art school. I graduated in 2007 and I didn’t know what to do with myself. There wasn’t much going on in Brussels at the time, and many of the painters and artists back then that I admired the most were Americans. I asked all of my teachers, “Do you have any idea who I could work for there?” Nobody knew anyone, but one person said, “Hey, there is this little book, it’s like the yellow pages of the art world. It’s called Art Diaries International.” It doesn’t exist anymore, but it had the addresses of all the studios, artists, curators, and all the galleries around the world. I bought that at the bookstore and then made a list on my flight over to New York of who I would like to work for. Three days later I went down to Tribeca and stopped in front of Richard Serra’s studio, smoked maybe 15 cigarettes, and then found the courage to ring the doorbell. And this guy Allen Glatter answered. Of course, at first he told me to fuck off, but I insisted and I had a portfolio and someone else had called sick.

SANDSTROM: Oh, perfect.

ANCART: He said, “Do you have a phone?” And I had a phone with $20 worth of credit on it, so I was hoping no one else would call in between. Two hours later he called me and said, “Be here at this time.” That’s how things started for me. It was not a slow progression, and things started working out pretty quickly. I arrived here at age 27, and by the time I turned 31, I could pay for things. I could buy oil sticks and take friends out to restaurants.

SANDSTROM: Was it overwhelming?

ANCART: No, not at all. If anything, I was just very happy to receive some cash. I remember the first time I realized that there was an exchange value was when I was 14. I could draw pretty much anything, but I was very good at making drawings of naked women. I was 13 or 14, and the guys that were older—because there was no access to pornography or anything—they would ask me to draw for them. So, I would trade snickers bars or protection for drawings of naked ladies.

SANDSTROM: Oh, wow.

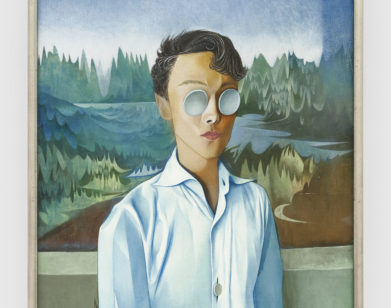

Francis Picabia. Sans titre, Ca 1943-44. Signé en bas à gauche. Crayon et huile sur carton. 75 x 52,2 cm.

ANCART: Very often I was asking if the ladies could hold a gun. They said no. But I realized that there were some transactional possibilities if you could make something desirable. But I worked for Richard, then a little bit for Jenny Holzer. I met young people who were also assisting other artists, and I met Olivier [Babin] who founded C L E A R I N G. He helped me a lot because he knew people. I didn’t know anybody. So whenever he would have a studio visit, he would send the person to me and I would have a studio visit too. There are many people who endorsed me over the years. I’m thinking about Michel Francois, this Belgian sculptor who’s about maybe 65 years old today, who literally picked me up from the gutter and introduced me to people saying, “I think this guy is making interesting work.”

SANDSTROM: I wanted to talk about the resurgence of interest in Picabia in the past few years, particularly in New York. There was the David Lewis show a year ago, and the Michael Werner show next door. What do you make of it?

ANCART: Maybe people in New York all had a spiritual awakening at the same time and realized that perhaps it was unlike many other practices in the sense that it offers many different things and opens many different doors. If anything, maybe Picabia would be comparable to the great philosophers who like to ask questions more than answer them.

SANDSTROM: Do you see yourself in him?

ANCART: Definitely. I don’t believe in meaning. I’m a little bit like [Albert] Camus in that I think absurdity is an ontological condition that is attached to all things. People have this very human desire to bring meaning to every single situation, which is maybe symptomatic of a general insecurity, or finding this larger sense of purpose. But perhaps the more profound reality is to understand that maybe life has no meaning except to love and live and die and make a drawing.

SANDSTROM: Right. And I know you’re not exactly a scholar of his, but you’re a fan.

ANCART: It’s difficult for an artist not to find yourself locked into your own psychodrama, or to find the courage to do one thing and then all of a sudden do something very different. There was this small show of Picasso at Montmartre a year ago, where there were those paintings of big pink ladies carrying water. He made them in a house somewhere in France and at the same time he was making these cubist guitar players. And it really floored me. I thought, “Man, how does he do that?” Perhaps they do it because one of the keys to success is to be very detached, as Buddha would say. If you stick to the territory that you know you can’t really call yourself an explorer. In order to explore, you must get lost.

SANDSTROM: How do you detach?

ANCART: I try to practice the Zen, almost the chivalrous art of not giving a fuck about anything.

SANDSTROM: How’s that going?

ANCART: Well, you have to remind yourself that you must remain polite and kind and things like that. But when it comes to my work, I try not to take it too seriously because I don’t think that painting is by any means an extremely serious activity. I rather think it’s the opposite. There are very serious things like cancer or famine or homelessness or poverty. Painting, not so much. I think art probably is one of the only activities that doesn’t need to be framed by rationality or that can escape the shell of meaning. I was always suspicious of art that is about something: why doesn’t it offer me the possibility to read it with no pre-established knowledge? That’s also the reason why I moved to America, because I had the strong intuition that there was work being made here that people would embrace with their chest and not only intellectually. I would say that Picabia is, because I’m a liker or more than a hater. I like to like things. Even if I don’t like it, I try to find something good in it for me.

SANDSTROM: What do you hate?

Francis Picabia. Sans titre, 1946-47. Signé en bas à gauche. Huile sur panneau. 50 x 38 cm.

ANCART: I don’t hate anything, it’s just that certain things don’t interest me and others have a very profound effect on me. Very often the effect would be that I want to go to my studio and work. I think it’s Artaud who talks about erudition by the soul of the feet, knowledge as the light. But I think that you can learn from nothing or from a very unspoken experience. I try to maintain that, because the way I work is that I wander around and I look at stuff because I believe it’s there. It’s a little bit as if I was in a giant shopping mall.

SANDSTROM: Your life is a giant shopping mall?

ANCART: Exactly. But I always try to have some sort of a democratic way of looking. I read a lot of comic books, I look at a lot of paintings, but I also spend a lot of time looking at corners or the floor or what have you. I like to look at everything in the same way without any hierarchy. This is how I find the elements and somehow decide that if I combine certain things together, I will end up with something that may not be new, but that will definitely be a new combination in the same way that it’s always possible to make a new sentence with the words that are already there. There’s new words every year because somebody invents something, but that’s not going to change the history of literature.

SANDSTROM: Do you want to chat about this beautiful painting? You made it with oil sticks.

ANCART: I did. It’s obviously about the natural world, and it came to me a little bit by surprise. I didn’t know that the canvas was flat on the table when I made it and that I was working on something else at the same time. All of a sudden I was watching it unfold as I was making it. And then I thought, “Oh, it’s amazing how absolutely nothing happens in this painting.” I was very happy about that.

SANDSTROM: It actually reminds me of what you just said about the world being your shopping mall. It’s very textural and makes me want to reach in and grab it.

ANCART: Yes. Also, it is a smaller size painting. Sometimes I work on very large canvases, so you don’t have this instant gratification. They move very, very fast. And then I thought that perhaps because I’m attached to that work in particular because it looks a little bit like it’s been dreamed directly onto the canvas, and I think that’s something you find throughout the exhibition. At the beginning, the floor was this weird brown color and the walls were very white and I thought it was too strict. So I asked for this beautiful carpet and I painted this semi-gloss beige on the walls to complete the environment, because this is how I dreamed of the exhibition. I thought, “I would like to make it very cozy.”

SANDSTROM: Yeah, it’s cozy in here.

ANCART: It is cozy, right?

Installation image of Francis Picabia & Harold Ancart: 7 Paintings and 1 Painting. Photo courtesy of Fleiss-Vallois.

SANDSTROM: It doesn’t feel like we’re in a gallery, which is ideal. What do you dream about?

ANCART: I dream about all sorts of things. Sometimes I dream of paintings, sometimes I dream of awkward situations that relate to things that are happening in my life. I dream of friends. I had this crazy idea the other day. People talk about how when you meditate, that’s when the energy flows and that’s the natural way you should be. And then I thought, maybe the only reason we are awake is so that we can feed ourselves and then secure a safe place for us to be able to sleep. Then the main purpose of life would be to be asleep and that the waking time would only be there so that you would make it possible that you would have the best sleep ever.

SANDSTROM: I’ve never thought about life that way, but I hope that’s true.

ANCART: I hope it’s not because it means that I would be pursuing all sorts of dreams and goals in the waking world, and I would have completely disregarded the sleeping one.

SANDSTROM: I have two more questions for you. Can we get into your departure from [David] Zwirner?

ANCART: Does it have anything to do with this great exhibition?

SANDSTROM: Well, what would Picabia have done?

ANCART: I think Picabia would’ve done what Picabia did, which is be as free as he can be. If he all of a sudden doesn’t feel happy somewhere for whatever reason, he would walk.

Francis Picabia. Danseuse de french cancan, Ca 1942-43. Signé en bas à gauche. Huile et crayon sur carton. 105,5 x 76 cm.