RETROSPECTIVE

Gary Simmons on Censorship, Minstrelsy, and the Scourge of Art Fairs

It’s the VIP preview day for Gary Simmons: Public Enemy at the Pérez Art Museum. On a characteristically hot afternoon in Miami, the air is cool and still in the spacious galleries of the museum, a welcome respite from Basel mania, which the artist likens to “Target, or something.” Growing up as a West Indian kid from Queens, Simmons started doing custom paint jobs on cars and selling his drawings for $100. He is steadfast in the belief that you cannot become an artist alone, crediting figures like the curator Thelma Golden and the late critic Greg Tate in his development. Now, with Public Enemy, Simmons can witness the breadth of his career—approximately 70 works, spanning three decades.

Simmons has an encyclopedic knowledge of hip hop, film, and sports, waxing lyrical on each subject unprompted. It’s a kind of curiosity and visceral relationship to popular culture that those who’ve grown up with the internet seem to have lost. He was on hand for the birth of hip hop in New York and recalls hearing Public Enemy for the first time at a club—“That was life-changing for everyone in the room,” Simmons exclaims. On a panel for the show, co-curator Jadine Collingwood calls Simmons “a savant,” a word that rings in my ears as I visit the exhibition for a second time.

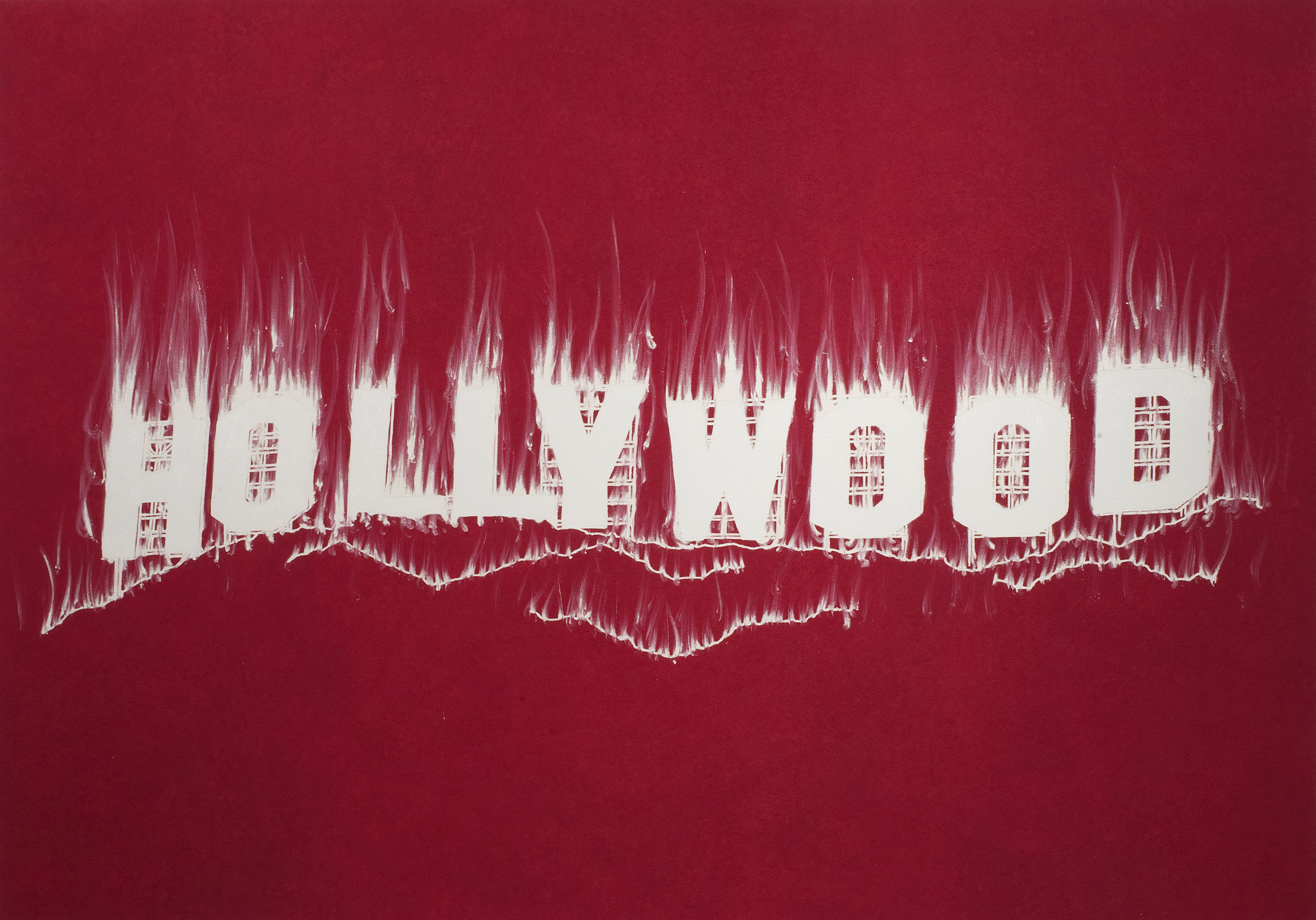

Public Enemy is an antidote to the bloated consumerism of Basel. Each gallery focuses on one of the artist’s thematic obsessions; viewers are confronted with the Black athlete’s place in culture, white supremacy in the classroom, and the racist tropes of Old Hollywood. A few days into Art Week, and after several technical difficulties, I got to talk to Simmons about the art market, horror films, and the politics of boxing.

———

MARLOWE GRANADOS: It’s kind of strange at this point in your career, with much more work ahead of you, to have a retrospective. How is it walking through the rooms?

GARY SIMMONS: It’s a good question. It’s a mixed feeling. It’s a good feeling, without a doubt. You look at that much work and you think, “Wow, how can that much time pass?” In some ways, it feels like 10 minutes ago. And in other ways, certain pieces feel so long ago. They’re like your kids or something. They kind of grow up and go to college and move out and live on their own and then they come back and visit and they’re like, adults.

GRANADOS: A lot of your large-scale projects are site-specific, because they can’t be removed, like many of the wall murals. What’s it like to remake a piece you initially made decades prior?

SIMMONS: In my case, I could probably do a wall drawing with the same sort of base image 10 times in a row and you’d have 10 completely different drawings. They’re all based on how I feel that morning, how my attachment to the work changes over time. The desire to create a strong political image still stays. That’s the constant, the baseline, if you will. What’s exciting is that, if I was to do the glass house even today, it would be different than when I installed it three weeks ago. That keeps it fresh. It’s always kind of living. And in some ways, that’s a sad and telling comment on the way some things haven’t changed over 30 years.

GRANADOS: I think it’s also the way that each generation of young people eventually discovers injustice in the world and gets radicalized growing up in certain circles. It’s very clear that there’s all this market pressure to censor artists’ politics and people want to sanitize art to bend to the market. What are your thoughts on that?

SIMMONS: It’s a concern. The market has changed so much since I started. My first drawings, I think, sold for $100 or $150 a piece. I was just happy enough to buy drinks for my friends that night when I shot pool. Then the market crashed. We were looking at artists coming out of the ’80s who were your first real, serious millionaires. We’ve seen a couple generations of artists since that have never experienced an art crash. They have no idea what that even means. The scaffolding to keep the art world moving through financial ebbs and flows is there now and wasn’t there in the early ’90s. You went down with the ship. Now, the art world has this parallel existence; it’s almost like a safety net for a lot of investment people. You find them throwing money into the game and taking risks on artists that haven’t really gotten their legs underneath them yet. Some of that is dangerous for the artists. If you throw too much at a young person too soon, they start to get a very skewed idea about what and why they’re making this work. You start to adjust to a certain audience to keep it going. That’s a scary place to be, and you see it repeatedly. It’s a shame that there isn’t more charged, in-your-face imagery when you walk into a gallery, and I do think that there’s a cleansing and sanitizing of work. A lot of collectors follow the hemline. Art Basel’s no place for an artist to actually see art. It’s not even like Century 21, it’s like Target, or something. There’s no real rhyme or reason or integrity to why those things are there. It’s just commodities exchanging.

GRANADOS: What advice would you have for young artists in that position?

SIMMONS: For a younger artist, the playing field is so much wider. There’s a lot of people that don’t have the right intentions and you have to avoid them. You need to align yourself with young, hungry, intelligent curators that are in it for the right reasons and line up with why you are making this stuff. We’re not making decorations for hotel rooms. We’re making real art. And you need to have somebody that’s around you that’s supporting those ambitions. Where I had somebody like Thelma Golden, a younger person needs somebody equivalent. Nobody does this shit by themself. That’s the biggest myth. And stay away from art fairs.

GRANADOS: Stay away from art fairs. I think about this a lot when I look at athletes and politics, and I think it goes into people wanting a good, well-behaved artist or athlete, especially if they’re Black. They want someone to be able to perform for them without reckoning with the individual and their views.

SIMMONS: Absolutely. Boxing was a big part of my family existence. I can remember being in the basement of my house in Queens and my father and his friends listening to the Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the radio as if it was on a big screen. You look at somebody like Joe Louis and Max Schmeling, you look at Sonny Liston when his name was then Cassius Clay, or you look way back at somebody like Jack Johnson, who was one of my heroes. Jack Johnson is this huge, menacing Black figure. When he was boxing, he would just annihilate everybody and they feared him so much that they stopped him from boxing in the United States. He had to go to Europe to fight because nobody would fight him here. He would date white women and drive Cadillacs. Every statement, the way he carried himself, was political. They’re almost like saints or something. Boxing is something I always go back to as a kind of metaphor when I start to dig into certain issues.

Step into the Arena (The Essentialist Trap) (detail), 1994. Wood, metal, canvas, Ultrasuede, pigment, ropes, and shoes. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

GRANADOS: I’m a film girl, and I have such an obsession with pre-code films. So I loved all your film influences, especially horror. I was wondering about the films that you have revisited over the course of your life that have seeped into your work.

SIMMONS: My go-to’s are some of the classic ’50s horror movies. Things like Creature From the Black Lagoon, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, going all the way back to Frankenstein, a classic. Night of the Living Dead is probably one of my top two or three movies. Candyman, another one. Nosferatu and Metropolis, too.

GRANADOS: We’re nearing the holidays, and people rewatching films like White Christmas and Holiday Inn. I’m sure you’re aware of the Blackface minstrel show scene and the moves to edit it out. I would love to hear your thoughts on that.

SIMMONS: To me, it’s almost painful to erase it. Those experiences and those people, you’re saying they didn’t exist. And they went through a hell of a lot of stuff for us to be able to even sit and discuss it. So to erase it is ridiculous. I think the idea of erasing monuments is equally ridiculous. You can’t edit out the past like that. It’s irresponsible, in my opinion, to extract those figures. I also have a problem with people running around trying to squash people’s voices on college campuses. I have a daughter that’s about to go off to college. The idea is that she’s going to meet other people from different backgrounds, different cultures, and have those exchanges in a healthy environment. You’re supposed to go to college and meet a whole bunch of other thinking people and have those kinds of discussions. Sometimes it gets heated, and that’s okay. To shut that down, well that’s really dangerous.

GRANADOS: Oppositional thinking seems to have been devalued. I always feel like if you’re around “yes” people too much, you become a toddler.

SIMMONS: That’s exactly my point. You couldn’t have said it better. And what is the use of that? That’s not why I went to college, that’s not why my wife went, and I’m sure it’s not why you went.