gallery walkthrough

From the Senegalese Coast to the Hudson River: the Liquid Confidence of Khari Turner

“I imagine the show as a transition into a new life for me,” says Khari Turner of Breathing Water into Air, his new show currently on view at SoHo’s Ross-Sutton Gallery in New York. For the Harlem-based artist, the inspiration for the show—its title and its contents—came from a child birthing video he found on YouTube. “In the comment section, someone said that the hardest breath is the first one you take after transitioning from fluid sack to air,” he explains, via Zoom, from the gallery.

Breathing Water into Air serves both as Turner’s first solo exhibition in New York City and as a kind of resurgence. “It’s a birth and a rebirth at the same time,” says the Milwaukee-born painter, who recently committed to dedicating his life fully to his art practice. “I use a lot of water in my work, so it this focus on transitions just made sense.” The show features twelve paintings, all created in the depths of the pandemic, which seamlessly blend abstraction with figuration and, most notably, water with ink. The artist collects water in his travels—from the Senegalese coast to the Hudson river—and brings it back to his studio, where he mixes it with colored inks. Mixing saltwater with ink creates a paste-like solid, while freshwater and ink yields a silkier liquid: “It’s a constant back and forth between freshwater and ocean water,” Turner explains. As a result, his work seethes with textures, producing endless permutations of vein- or root-like ridges and liquid swirls through his manipulation of materials.

To celebrate the exhibition’s opening, Interview caught up with Turner at the Ross-Sutton Gallery this week. Below, the artist reflects on his affinity for water, the beauty of surrendering agency to his materials, and the role of poetry in his practice.

———

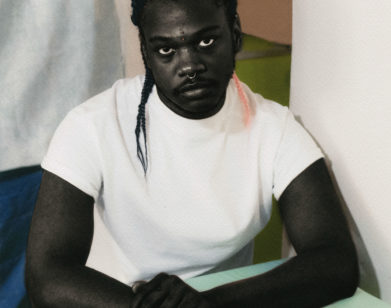

Thank you for being my lighthouse, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, sand, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, and water from the Pacific Ocean on canvas. 60 × 72 in / 152.4 × 182.9 cm.

“This was actually the first piece that I did for the show. I was thinking, ‘In what way is this piece gonna set the vibe?’ It’s named after a Javon Johnson poem about being a lighthouse. He talks about not appreciating somebody who was his lighthouse and how that affected his relationship with that person. I realized that I don’t ever say ‘thank you’ to the material. I try to use it and I try to be a part of it, but I don’t actually say ‘thank you’ to it. In this one, the arms beam out like a lighthouse. People always ask me, ‘Why do you take out the eyes in your work?’ There are multiple answers to that, but I ask, ‘When you look at my work, what do you think about? Are you thinking about the person in this image?’ They often say no, and it’s because the eyes are gone. When you can’t connect to the person in that way, then you have to go with the emotions they’re depicting or even the color. The water makes you connect to the figure’s body, as well as yours. It’s a body of water connected to a body of water through abstraction.”

———

Swim Lesson, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, water from the Pacific Ocean, African Mahogany, and Yellow Pine on canvas. 84 × 120 in / 213.4 × 304.8 cm.

“I knew right away in creating the layout for the gallery that the central back wall had to have one large piece on it. I wanted you to see this piece from outside the window and right when you walk in. The blue really brings you in and it just felt right. Essentially, I thought a lot about the spirit of water. This one was all about leisure. There was nothing happening to this figure at all. They’re just relaxing. I only allowed the tube to be a minuscule part of the work. It’s made out of African mahogany, yellow pine, and white oak. The reason for the yellow pine and white oak is because that’s the same wood that was used to make schooner ships that were used for the slave trade. With the African mahogany, I wanted to talk about this idea of people recognizing themselves as a type of wood. For Black people, it’s things like ebony or mahogany. It’s a really interesting conversation. I enjoy thinking about the fact that we’re made of wood, one way or another. With the tube, a lot of this is me thinking about the past and reclamation. I wanted this piece to be about leisure and how you address history. I didn’t want it to be sad, because sometimes the way people deal with history is really gory. We know that it’s our history, and right now, I want to be lounging in a pool.”

———

A harmony of spirit, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, sand, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, and water from the Pacific Ocean on White Oak. 48 × 48 in / 121.9 x 121.9 cm”

“This was a fun and insane piece. I knew I wanted to do a side profile that’s two pieces—a diptych. One half is abstract and the other is figuration. In doing this piece, I wanted those to be set up in a way that if you separated them, they could have a conversation and if you put them together, they could still have a conversation. So it’s a piece with three conversations happening at the same time. I knew I wanted to do the profile and a circle, but I couldn’t figure out how to make the right type of circle. The oval shape came because I have another, smaller oval piece in the show. I used that shape and traced it over the face. In the same way, there are two similar shapes happening near the earring. So this piece was really cool because it just came together. I usually have somewhat of an idea as I’m going into a piece, but I usually let the material decide how it’s gonna go. In this one, I really had no clue. And as I was staring and finishing, I was like, ‘Oh yeah I like this.’ If you look at the top of the hair above the oval, there is a point where the hair just goes off into a tangent and then falls off the edge of the work. So in doing that, I’ve been thinking about how I allow people to see the water as water. The hair was a certain type of shape, but once water gets to a point where it can’t go anywhere, it’ll sit on top until it can find a place to go. It’ll just overflow. For this piece, I wanted to allow the overflow to show. The piece decides where the hair ends.”

———

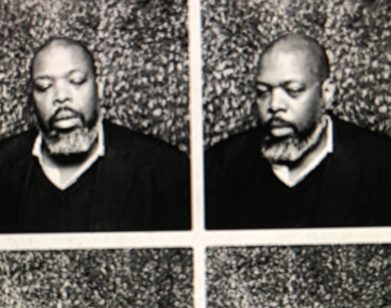

Phantom in the rearview, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, sand, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, water from the Pacific Ocean and acrylic sheet on White Oak on Yellow Pine. 48 × 48 in / 121.9 × 121.9 cm.

“This is another diptych. I’ve been working with this protractor shape. I like old ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s minimalist art. I’m thinking of Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and all of these different artists who used shape in their work. That’s why there are so many abstractions in the show. The figure does one thing and the material does another. With this piece, I started off with the idea of the journey of water that’s happening in the work. There’s this boat shape that’s basically two protractors and a rectangle. So, how do I deconstruct, reconstruct, and rethink shape in different ways? In the same way that I thought about the oval shape in the other piece, it started off as one thing, and then it led to something else. There was stuff that I was going to add to it, but it felt like it was done. I was going to paint the durag, but then I was like, ‘No. It would be more interesting to do a wood durag rather than a regular painted one.’ There’s a shape in the middle on the left side where wood meets the protractor. I thought about this like yin and yang because the bottom of the left piece has white sand and the top of the right piece has black sand. There’s a lot of me trying to think about how the shapes encounter and bounce off of each other. So you see that rectangle shape on his shirt, that blue going across the image, and then the shape on the side. All of these were made out of the same water that I made the skin out of.”

———

No Secret in this Secret Garden, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, water from the Pacific Ocean on canvas. 48 in diameter / 121.9 cm diameter.

“This piece is so funny. I made it angrily. So there’s a lot of texture on this piece. The leaves are basically coming off that thing. When I was going into it, I wanted to do it in a certain type of way. And I keep telling you, I cannot do what I want to these pieces. The work tells me what it needs. So I started off saying, ‘Oh I’m gonna do it like this’ and the piece said, ‘Nah.’ So I got angry, but I kept painting. I kept throwing paint and water on there, letting it drip. If you look at the bottom, it just drips everywhere. So I finished the piece just like that. I named it No Secret in this Secret Garden after the Maya Angelou poem called “The Secret Garden.” I thought about the painting revealing itself to me. This garden was going to happen regardless, I just had to find it. We know there are no eyes, but the reason I show the nose and the lips is to contribute to the conversation about Black beauty and those features. I’m reclaiming those things. Also, the face is slightly up and pointing towards the sky. There’s a regality with the gold earrings and it’s like ‘You just happened to be a presence in my garden. Thank you for coming. It’s no secret. I’m not hiding.’”

———

“Breathing Water to Air” is on view at Ross-Sutton Gallery until August 7, 2021.