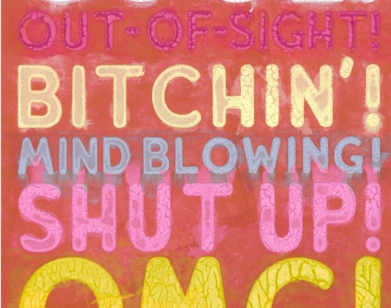

ICONS

Francesco Clemente and Ed Ruscha on Rejection, Religion, and Getting Too High

Francesco Clemente and Ed Ruscha, photographed by Nicole White.

“Every world is a miniature hell if you stay idle,” Francesco Clemente said to his old friend Ed Ruscha on the phone last week. The Naples-born artist is a vessel of striking one-liners that are just as piquant and lyrical as his own paintings. Inspired in part by his early rejection of Catholicism and his years spent in India, Clemente’s works are instantly recognizable as earnest and childlike explorations of himself and life on earth (and often punctuated with his signature menacing, beady eye). His new exhibition, which opens at Lévy Gorvy Dayan this week, includes a series of paintings made over the past year that demonstrate the essential characteristics of his work: they’re heavenly, creepy, exploratory, and proudly sincere. To mark the show’s opening, the two artists got on a call to talk about rejection, getting too high, the Clemente Martini (available at the Clemente Bar), and a fateful early encounter with Black India ink.

———

FRANCESCO CLEMENTE: Ed, hi.

ED RUSCHA: Francesco. How are you?

CLEMENTE: I’m really well. I’m delighted to hear your voice. I wish I could see you in person.

RUSCHA: Good to hear your voice. I want to thank you for inviting me to your studio when I was there last time. Besides being full of recent paintings, I also got to see this wraparound view of life on the street. You really have a studio from heaven.

CLEMENTE: I thought California was heaven.

RUSCHA: Well, I still think it is. But you’ve got a different kind of heaven there. It must put you in a good mood to be in that place.

CLEMENTE: It puts me in a good mood to be talking to you. We have known each other for a long time now. I think Raymond Foye introduced us when I came to L.A. for an exhibition, no?

RUSCHA: That’s right, back in the ’80s or something.

Cigarette. Watercolor on paper. 59¾ × 79½ inches (151.8 × 201.9 cm).

CLEMENTE: Even though our work has two different chronologies–yours is a little older than mine–I was aware of what you were doing, especially in my formative years in Italy. I always said that you were rescuing painting from the dictatorship of conceptual art. I always was inspired by that, and followed in your footsteps with a different vocabulary.

RUSCHA: Well, when we met you were part of this New York art scene with Lawrence Weiner and some conceptual artists, and I loved that the art world produced conceptual art and figurative art and that it was somehow all compatible.

CLEMENTE: Yes. In a way, I think we both believe that what makes an artist different is that we believe in the idea of description, not prescription. We don’t tell people what to think, we show them options that allow the audience to think with their own mind.

RUSCHA: Good way to look at it. I’d like to ask you this question about growing up. Were your parents encouraging? Did you get some lift from either of them, or maybe both?

CLEMENTE: Yes. My parents were extremely cool. I realized that the first time they came to visit me in New York, they looked around my big loft in the early ’80s, and they said, “Well, Francesco, you have to remember that you sat on a step for 10 years doing nothing.” And that day, I admired them very much. During those 10 years when I was sitting on a step doing nothing, they did not object. They did not think I was wasting my time. In fact, I was not wasting my time. I was somehow accumulating reasons to make a painting.

RUSCHA: Did you have a specific moment when you said, “That’s it, I know I want to be an artist. Period.”

CLEMENTE: I became an artist by default, in a sense, after a very intense psychedelic experience. I decided I really did not want to be anything at all. I did not want to be part of what looked to me like a game of authority, of manipulation, basically a very dreary game of power. I didn’t think about being an artist, but I thought, “What kind of lifestyle can I work for in order to have a reasonable life?” That’s all I did. Did you do the same?

RUSCHA: Well, something happened to me. It was an accident. I had a bottle of Higgins Black India Ink and it got knocked over and spilled out onto a table. I must’ve been 10 years old, and I looked at this thing and I could see that it would be a mess to clean it up. So I just let it dry out, and it became very crusty. But the blackness of it always stuck with me. If there’s one particular moment that led me into the arts, I would say that’s it. So maybe I could call myself an accidental artist.

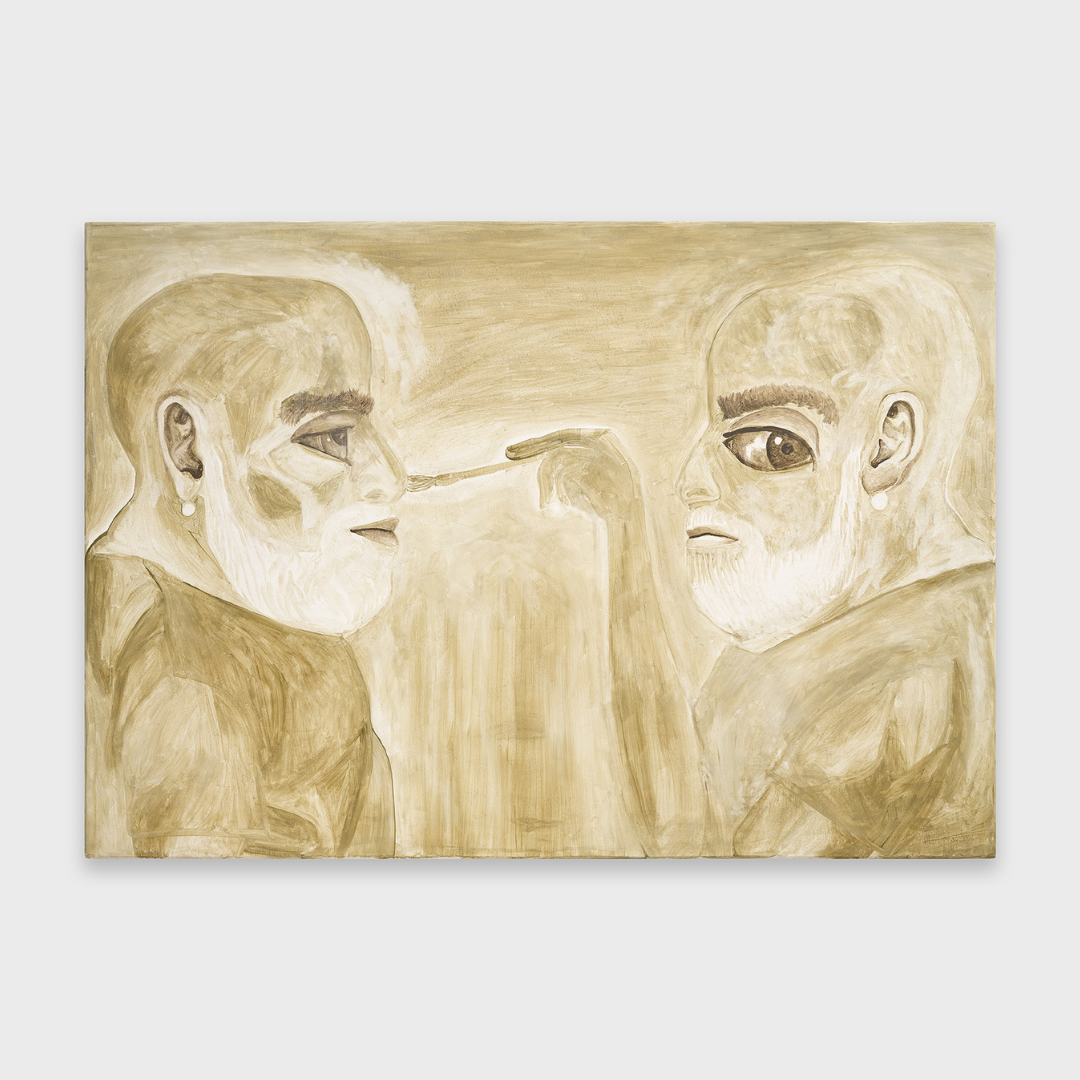

Brush. Fresco on aluminum panel. 46 × 66¾6 inches (116.8 x 168.1 cm).

CLEMENTE: That’s a wonderful story of origin. I love to hear about India Ink because in the very early stages of my being an artist, I covered the floor of my little apartment in Rome with ink drawings. I considered them to be some sort of amulets inspired by a particular drawing by Antonin Artaud, who when he went crazy and was in a mental hospital made these drawings as protection for his mind to survive. So in a sense, my beginnings are also made of India Ink.

RUSCHA: Yeah. Also, I know you have a leaning towards books.

CLEMENTE: Yes.

RUSCHA: I’ve collected Hanuman Books. Are you still making those?

CLEMENTE: No, those I don’t make anymore. They were initiated together with Raymond Foye when he came to visit me in India. But I always had a passion for books, just like you.

RUSCHA: You were also into beat poetry at one time, and I found that to be a really vital force myself. I connected that with Franz Kline because of his black and white paintings. I thought, “Well, with these printed black words on white paper, you could look at the text on one side and an image on the other, possibly.” That always reminds me of what somebody asked Captain Beefheart. They said, “What is music?” And he said, “Black ants on white paper.”

CLEMENTE: Oh, that’s good. Captain Beefheart was a painter too. I remember seeing his paintings back in the early ’80s.

RUSCHA: So it all connects. What do they say? “All art comes out of other art.” I’ve noticed going through your work here that you have a leaning towards self-portraiture, and I’ve never attempted to visualize myself on paper or on canvas. But the images that you put on paper were all distorted. I mean, it was you, but it didn’t look so much like you until I pitched that image sideways.Then I saw that you were doing anamorphics.

CLEMENTE: Yes. Have you made anamorphic works? It seems like something that could be part of your vocabulary.

RUSCHA: I guess so. I always remember Mad Magazine because on the back cover they had anamorphic images. They were doing this in the comic book world back in the ’50s or ’60s. That was like an alarm bell for the future. I know there’s some places in Italy where they have done hallways of anamorphics that are really impressive.

CLEMENTE: There is a famous secret one in a corridor on top of the steps of Piazza di Spagna in Rome, but I’ve never seen it. They don’t let anyone in there. I guess mine were voluntary anamorphosis. But not really, because many of the early self-portraits were made looking down at my body.

RUSCHA: All right. Boy. You are from Naples, is that right?

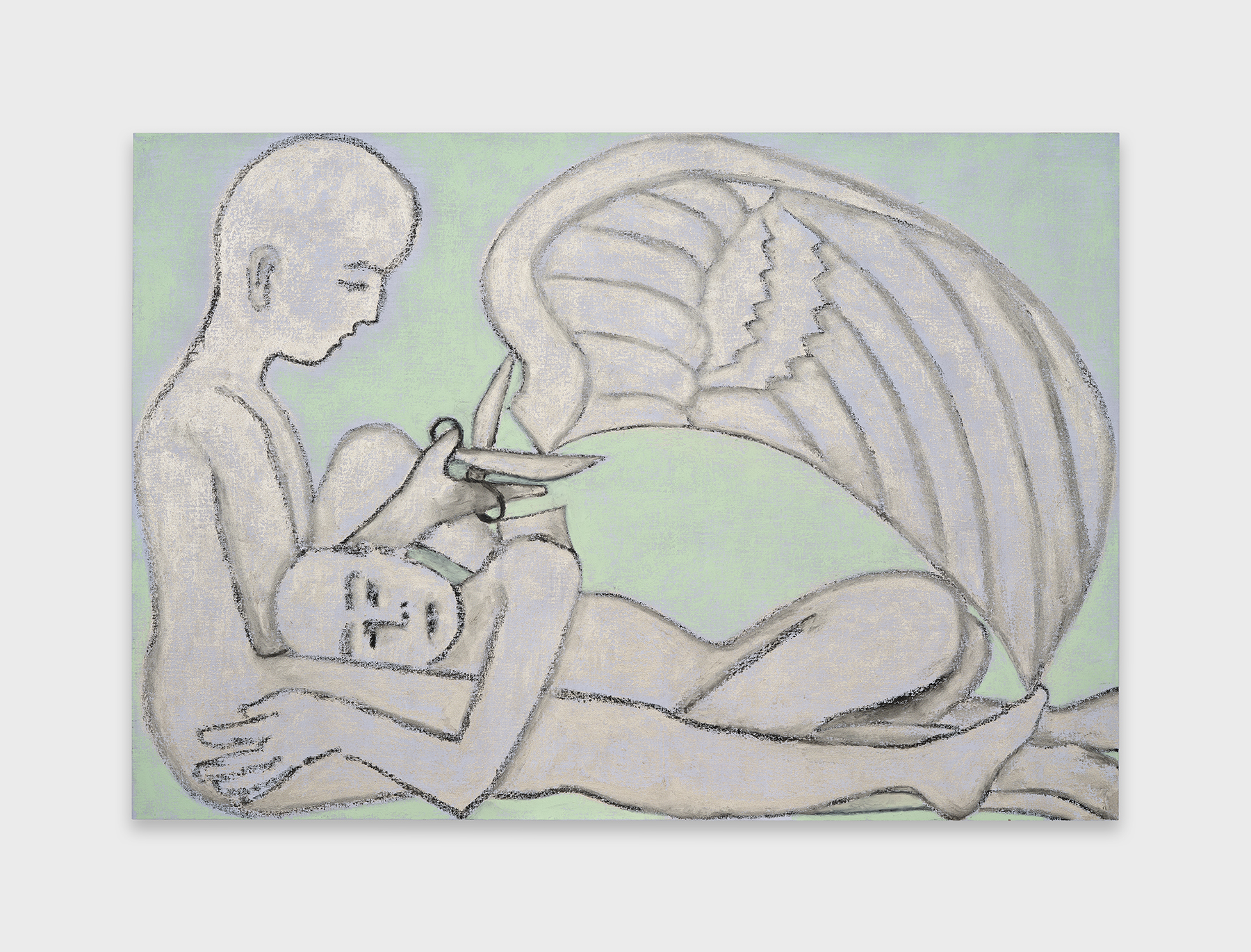

Scissors. Oil on canvas. 46 × 66¼ inches (116.8 × 168.3 cm).

CLEMENTE: I grew up in Naples. And as you know, Naples is a wild city with a very powerful pagan atmosphere. All the churches are built on top of ancient Greek or Roman temples. They preserved the parts of those temples in a Catholic disguise. So from the beginning, I was always on the side of contamination, of overlapping, of a confusion of languages. I’ve always been attracted by that.

RUSCHA: Yeah. You were a raised Catholic, like myself?

CLEMENTE: Again, the same discussion that is valid with the ancients from the history of art is valid for religion. Just because you’re in a Catholic environment doesn’t mean that that takes over. Actually, not just for me, as a rebel teenager, but for my parents too. They were totally against all of that. I was more attracted later on in life by religions that are related to community.

RUSCHA: Yeah. I mean, I no longer consider myself a Catholic, but I was raised that way. And I got a particular energy from just looking at the Stations of the Cross and ceremonial vestments, incense, and trappings. I feel like it’s leaked into my work somehow or other without flying the flag of Catholicism. So, I was just influenced by the superficial effect of the Catholic Church, and it kind of set me apart from my Protestant friends.

CLEMENTE: Yes. I make much of the fact that I spend a lot of time in India, and I’ve had a very intense dialogue with the so-called “spiritual traditions” of India. On the other hand, don’t you think America is a truly spiritual place?

RUSCHA: I don’t see that. Well, I don’t know.

CLEMENTE: You can say no. I like your reluctance to accept that. It is an element of your work that I truly love, which is what I would describe as a “contained fury.”

RUSCHA: Contained fury?

CLEMENTE: You know some scholars have been writing about late style, about how an artist, when he reaches maturity, can either embrace the world and reconcile, and reach a new level of serenity. Or he can become even more of a rebel in conflict with the world, and begin to fragment, and destroy almost what he has done before. But I was looking at your work from the last 10 years, and in a way, you have always made your late work. There is an element of fury, which is disguised under the humor. And there is an element of serenity, which is expressed simply by the way you arrange the image. It’s a very unique combination of the two. Would you agree?

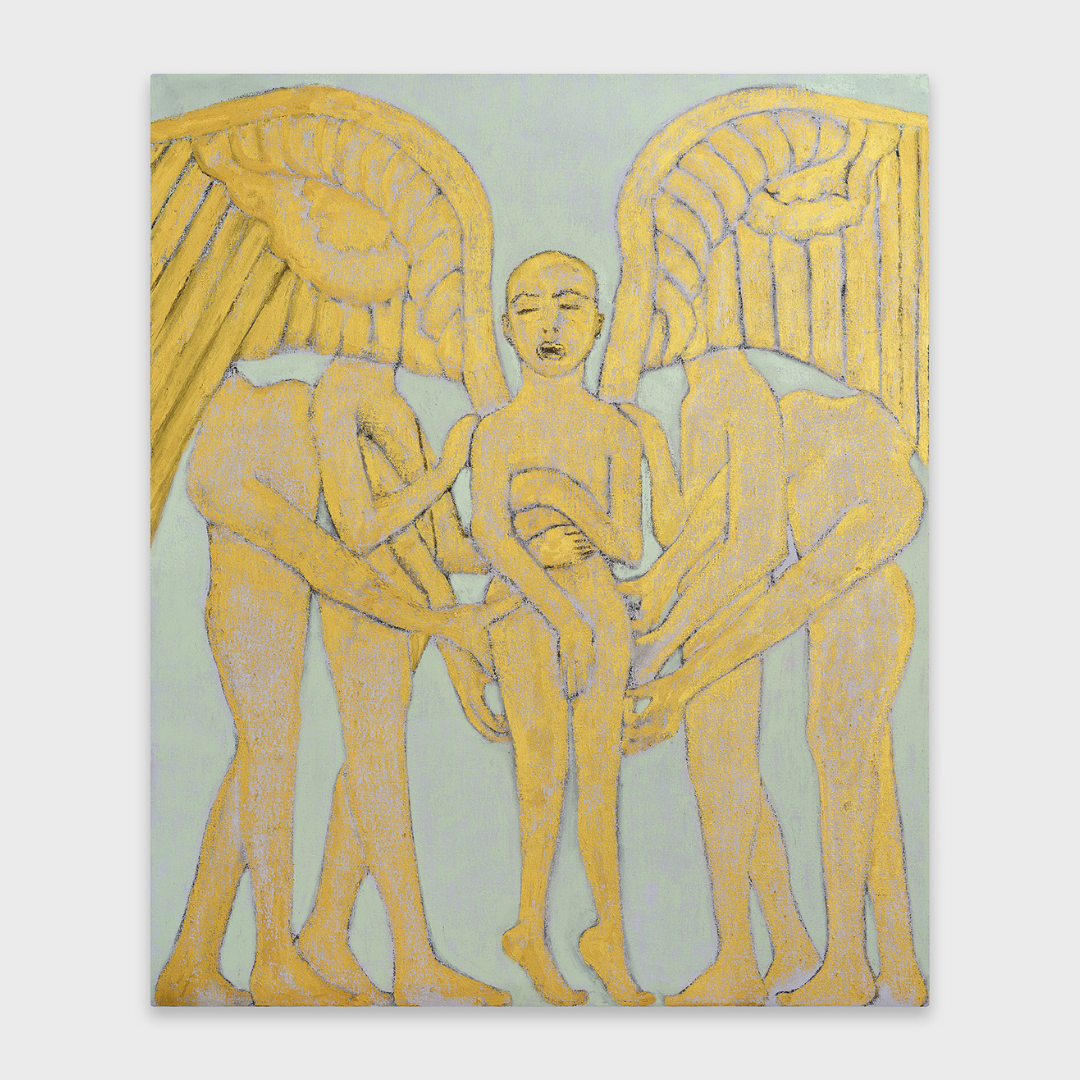

Fireworks. Watercolor on paper. 79¾ × 59¾ inches (202.6 × 151.8 cm).

RUSCHA: Yeah. As time passes, I think we earn the right to be pessimistic about things. I know a lot of artists go through that. I guess I emerge with some kind of optimism about the general art world, but not so much my position in it. I see these young artists, and a lot of people are aggravated by what they see, but I see some kind of promise out there. They make kamikaze art. They throw it up on the wall and see if it sticks, and I like that.

CLEMENTE: I totally agree with you. And of course, every world is a miniature hell if you stay idle. But in every miniature hell, there are some friends or people who inspire us who step out of the circle to be able to look at it.

RUSCHA: There are so many artists that are doing so many different things, it’s almost overwhelming to try to absorb it. You know, like my neighbor here, Kenny Scharf, who I met through you years ago in New York. He lives up on the hill above me, and he says he gets to look down on me, and I have to look up to him.

CLEMENTE: You have to explain this is topographically. He’s on the hill above your studio, right?

RUSCHA: Yeah. I went to his house the other night for dinner, and he had brought out a joint, and I puffed on it. I hadn’t had marijuana in almost a year, and I passed out. He instantly called 911, and the paramedics were there in like, 20 minutes. They came and treated me, and gave me blood sugar tests and got me back on my feet. But I just thought, “Kenny, boy, you’re used to this kind of stuff, but I’m not.” They’re making it too strong these days.

CLEMENTE: Can I put on record that Kenny is the best person alive? I love his spirit just as much as his work.

RUSCHA: So anyway, life goes on and we stay with it. I guess you like to travel, and you somehow get inspiration from all your travels.

CLEMENTE: Yes, but my geography is limited. It’s really New York and India. Somehow what is important for me is to live in a non-place, like a place in between. I miss India when I’m in New York, and I miss New York from India. Geography is important for many reasons. I always remember when I moved to Rome from Naples, I met Boetti, who was also 10 years older.

RUSCHA: Oh, Boetti.

CLEMENTE: He would come from Turin, and would make fun of me saying “If you travel from North to South, you’re looking for poetry. If you travel from the South to North, you’re following your ambition.” And you know I was this ambitious person. But in a way, is there an equivalent in America, if you go East or you go West. You went West. Were you looking for poetry against ambition, or maybe nothing of the kind?

Wings. Oil on canvas. 72 × 60¼ inches (182.9 × 153 cm).

RUSCHA: Oh, you’re thinking geographically.

CLEMENTE: Yeah.

RUSCHA: Boetti, I think I have a wristwatch he made. Did you know about that?

CLEMENTE: Yes, he made one with the dates of the year.

RUSCHA: Don’t the hands go backwards or they were upside down or something? It’s like he’s making fun of time. I read that you like Fra Angelico and Giotto, and those artists. I remember Giotto in Italy, and I came away thinking about how he depicted eyes. They’re so beady, so mean looking, and so interchangeable. You could take eyes from any of the subjects and change them around, and you still have the same expression.

CLEMENTE: Yes. One forgets how brutal the world was at the time that these paintings were made. I was reminded of this once when I took my small children, my twins, to see the Accademia in Venice. And after they came out they said, “Why did you show us all these horrible things?” And I realized that the subjects of all these paintings were the most violent and appalling scenes, which I never really thought about.

RUSCHA: Wow. Yeah. And then that leads you to say, “Tell the world they should all go.” The entire world should go to the Accademia because there’s so many vital things in there.

CLEMENTE: It’s true.

RUSCHA: You’re almost required to go see that, just on a world level. Well, Francesco, let me ask you this. What about critics? Did you ever get a bad review that you felt bad or good about yourself because someone’s put you down? Have you ever gotten a shake like that?

CLEMENTE: Well, I only remember the bad reviews. I don’t remember a single good one. And I’m also too arrogant to accept a good review. My favorite bad review is the one that was titled “Gucci Guru,” which I thought was a brilliant and funny title. But it really left me heartbroken because I wanted to be a guru, not a “Gucci Guru.”

Honey. Fresco on aluminum panel with artist’s frame. 71½ × 59 inches (181.6 × 149.9cm).

RUSCHA: Yeah. I had one particular moment with criticism. I got kind of a slap in the face when I made this book called Twentysix Gasoline Stations. And I thought it was a rite of passage to send the book to the Library of Congress in Washington. I thought, “Boy, I would have the endorsement of the world if they took this into their collection.”

And they sent it back to me and said, “We do not wish to accept this book.” And that was in the early ’60s. And I think today the Library of Congress might be an entirely different organization, where they have to accept everything that comes to them, even pornography or horrible things. But back then, I was really stunned to get that rejection letter. That’s worse than being panned by a critic.

CLEMENTE: But don’t you think that rejection is also a way to legitimacy?

RUSCHA: Yes.

CLEMENTE: But of course, you don’t want to be rejected to the point that you are left without a job. And on the other end, the measure of rejection is also a form of legitimacy, and it’s an occasion to cheer.

RUSCHA: Yes, that’s good.

CLEMENTE: I’m being an optimist, just like you said you are.

RUSCHA: Well, when I come back to New York, I’m going to go to the Clemente Bar and throw back a vodka.

CLEMENTE: Yes, the bar is a creation of Daniel Humm built around my paintings. But don’t just get a vodka. You must drink the Clemente Martini. Everything is Clemente in the Clemente Bar, including the Clemente Martini which is made with gin, vodka, green curry, and saffron.

RUSCHA: Not Coca-Cola, huh?

CLEMENTE: Not Coca-Cola. That is something I drank as a teenager.

RUSCHA: Hey, thanks for the tip. I’ll get that martini.

CLEMENTE: Yes. Hopefully, we can drink it together. And hopefully, it will have a much more corroborating effect than the joint from Kenny.

RUSCHA: Yeah, and then maybe we’ll have another and another and another.

CLEMENTE: Then, we’ll have to call 911 because I don’t really drink.

RUSCHA: Well, I guess we’ll wrap this up then, huh?

CLEMENTE: Yes.

RUSCHA: It was great talking to you, Francesco.