IN CONVERSATION

For Brigitte Lacombe and Catherine Opie, People Are Portraits Waiting to Happen

When curator Helen Molesworth introduced Face to Face: Portraits of Artists by Tacita Dean, Brigitte Lacombe, and Catherine Opie, the new International Center of Photography’s inaugural portraiture exhibition, she expressed her admiration for the photographers and their subjects with loving deference: “Artists are gods to me.”

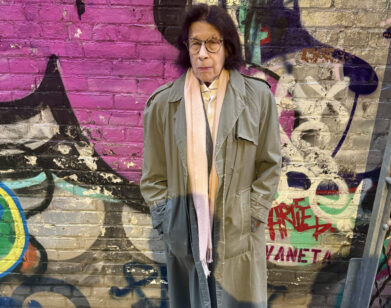

The ICP’s most recent show on Essex Street takes the form of a soaring modernist monument, all plate glass, matte steel, and slate gray concrete, a brutalist church fit for the worship of the relatively contemporary medium it presents. In Face to Face, housed in the museum’s towering nave, creative titans are transformed into idols by Dean, Lacombe, and Opie. An imperious, crisp-collared Fran Lebowitz hangs to the right of Eileen Myles. Lacombe and Opie’s larger-than-life portraits of Hilton Als, each vastly different but equally striking, sit side by side on the exhibition’s second floor. Though the scale and subjects are lofty, the exhibition is grounded by the intimacy of the portraits and their presentation. The majority of the wall text is composed solely of quotes from the subjects, many of whom are close collaborators and friends of the artists. Now collaborators and friends themselves, Lacombe and Opie sat down together on the morning of Face to Face’s star-studded opening to discuss exercising control in portraiture, their early forays into photography, and the subjects they never got to shoot.

———

CATHERINE OPIE: Okay, Brigitte. Brigitte. I love having a fake French accent when I say your name. Anyway, it is so amazing to be able to form this new friendship with you. And I feel like one of the great gifts that Helen [Molesworth] has done is to create a face-to-face between us to be able to talk about portraiture. And even though your work has surrounded and been out in the world for so long, I didn’t have a person attached to it. We talked yesterday about how we both want to make portraits of each other. And so my question to you is just how is friendship and portraiture combined in your life? Because I know for both of us it is.

BRIGITTE LACOMBE: Thank you, Cathy, because I feel exactly the same. I think one of the great things that is coming out of this shared moment is that Helen, who is the great curator of the exhibit and also a friend, made this happen—the show and our friendship. You see it, feel it, right away when you meet someone and there is more than shared interest. After not even 24 hours, we have a friendship. My life revolves around friendship, and my life is my work, and all the people that come into my life in a way are potential portraits. Some become portraits and some become portraits and friends, and that’s the best possible outcome. And I want to do portraits of my friends. But at the same time I feel like it is harder for me to do a portrait when it’s a friend.

OPIE: Why is that? Because it’s an interesting thing when I photograph people that I’ve never met before versus friends. I would say that I enter a portrait always from the same space. Though with friends it’s harder for me to actually control them, which is annoying.

LACOMBE: Of course, a big thing for us is to control everything.

OPIE: Exactly. It’s often that a friend wants to play with you when you’re working because they’re a friend, but you’re trying to do something else. It’s an interesting position.

LACOMBE: Yeah. Also, I feel protective of my friends. I don’t want them to be disappointed in their portrait. I’m aware of a lot of things that I might not be aware of with somebody I don’t know, like all their fragility or all their obsessive things. “No, no, not my nose. Not my profile.”

OPIE: Yeah.

LACOMBE: It’s an added complication. But it’s also a great advantage, too, because you get to a place of intimacy much faster. You’ve seen that expression or that emotion or that moment with them before, and you know that it’s a moment that is truly them.

OPIE: That’s true in terms of bodies. When I am asking people to move their hands or get into a certain position, if it’s a friend, I will have seen that and I kind of note that that’s their comfort zone. In portraiture, you read the body and people have very specific gestures in life. I know I always seem to put my hand behind my head. And it’s actually something that my dad always did, and I probably picked it up from him. One of my favorite moments in the exhibition, I mean there’s many favorite moments of your work, but the Maya Angelou photographs in terms of the way that they render her as a performer. I’m really curious about that sequence. I don’t know if you sequenced it or Helen sequenced it.

LACOMBE: Helen did.

CATHERINE OPIE: Yeah, because I know both of us gave over absolute control to our work.

LACOMBE: Complete control. Which is very unusual for both of us.

OPIE: I know. But there is that moment when you walk down that wall, if you’re reading it traditionally like a book where you’re going from starting on the left, you get to this beautiful moment you feel like you are being seen by her and her eyes are beautiful in showing her age. And what happens within a sequence for you when you face that? What are the emotions when you look at your own portraits that you made?

LACOMBE: It’s so strange for us to look at our own work, but thank you for describing what you felt. Because [Angelou and I] were there. We were there, we were present. We shared that moment in real life. I always wonder when people react, if it feels the same way we did in a way when we leave that moment. They just see it as an image, and somehow that moment is being transmitted to them. It’s a big mystery to me.

OPIE: I always feel like it’s a little lightning bolt that happens. Because in editing too, I always know that moment that I found when I was making it, when I’m looking at the contact sheets. It is curious that way. It’s indescribable when you know that you’ve got something.

LACOMBE: One of the images of yours that I love so much, is when suddenly you turn the corner and you see the oval portrait down the corridor.

OPIE: Mary Kelly from the back.

LACOMBE: Yes. And with her hands in her hair. Cathy, please tell the story that you were discussing with Helen about this image. Will she ever let her hair down? I’d love to know that story.

OPIE: Well, Mary Kelly is an iconic figure in the art world who has worn her hair the same way for over 30 years. And so when I made a portrait of her, I did it from the back. And with the oval, you’re playing around with that Victorian notion of cameos. And for me, it was a tease. “Would she take her hair down?” I did ask Mary Kelly to take her hair down for me, but she wouldn’t.

LACOMBE: In a way, it’s just as meaningful and beautiful that she refused, because she was very sure about the way she wanted to present herself for all these years. She was not about to break that.

OPIE: Yeah, she wasn’t going to break it even for me. But your portraits aren’t about that. What I love about them is they’re not about a forced experience. No kind of experience should be forced. Humanity is forefront always within your portraits. And they have this kind of beautiful honesty to them, which is always so problematic to say within the art world. They’re like, “Ugh, honesty, truth. Whatever.” But there is something within that and it’s important to hold those values.

LACOMBE: People find [my work] boring if they are looking for some great surprise or shock or something disturbing. But it’s certainly not about that for me. The portrait is about the collaboration between the person I photograph and myself. It’s not just me. Obviously, we talked about control, and I control everything beforehand, as we discussed. The location, the lights, who is in the room. But when we start, I see it truly as a collaboration with the person I photograph. Both of us have to be present and also generous and vulnerable. Not just the person you photograph, but yourself. It’s interesting, Cathy, because we do the same thing, but we are so different. And yet we are very similar. We have, at the end, a very common set of values in our work. They bring each other out next to each other. That was Helen’s idea to put us together, and I think it was a great idea.

OPIE: Yes, and with Tacita [Dean]‘s work, too. Even though this is a conversation between you and I, it’s a three-person show, with Tacita’s two films in this exhibition along with us. I love photography because it’s a frozen moment and it becomes history as soon as it’s taken. But with Tacita’s [films], it’s a live moment. It’s a beautiful way to reflect upon portraiture in and of itself.

LACOMBE: I hope people spend the time in the two screening rooms. It was nice that our first reaction when we finally saw the show was to run to our studio to do more portraits.

OPIE: I know. I looked at Julie Mehretu and I was like, “I’ve got to make your portrait.” I looked at you and I’m like, “I need to make your portrait.” What can I say? I’ve never not made portraits. I traverse through architecture and landscape and I touched upon the genre of photography in all these different ways. But at the end of the day, I think that portraits are probably what I love to make the most.

LACOMBE: Me too. Is there a point where you really realized that you were making portraits, or did it come gradually and then it imposed itself?

OPIE: I think it started when I made this body of work when I stopped being a street photographer. It was at the San Francisco Art Institute. I was in the school of [Diane] Arbus and [Robert] Frank, all of that history of photography was about carrying a 35 millimeter around and making street photographs in San Francisco. And I was living in a residence club and working from three to eight in the morning for my room and board to get through my undergraduate [program]. And I started making portraits of the people who lived in the hotel. And then I made a book of them, and I kept coming back. So even though the work continued to move through all the different genres, I knew that I had fallen in love with making portraits by making that body of work. When was the first time for you?

LACOMBE: One of the first things that I was commissioned to do—I never went to school or anything. I was a high school dropout, so opposite of you. But I was working as a photographer at Elle Magazine in Paris and one of my first assignments was to photograph photographers, which is funny now that I think of it. I photographed a few really important photographers. Helmut Newton was one. And that’s what comes to me now when I think of my first portraits. You said you discovered portrait work early on, but then you were going back to street photography. All the other types of photography that I do, that I go on a movie set or on travel or reportage. I mean, all of that feeds me and informs me and inspires me. And then I use that when I go back to portraits. I mean, everything is about looking and about absorbing.

OPIE: The beautiful thing that I recognized about you in forming this new friendship is your curiosity. I recognize you as being utterly curious. And I think that that brings an enormous amount of openness and joy into what we can do with a camera.

LACOMBE: It’s really about being curious to a fault. Everything is interesting.

OPIE: I know. I’m that person who’s constantly chasing the next butterfly. “That’s pretty, look at it. It’s fluttering that way. I think I’ll follow it.”

LACOMBE: We are so lucky. We are so privileged to do what we do and to love it and to be able to do it time and time and time again. And every time, like you said, there is a sense of joy in doing what you love. And it does not matter. It’s interesting, actually. It does not matter how many times you do a portrait. Every single portrait is a new one. Every single portrait is a new moment. And you’ve done it a million times before. But everyone is different. Everyone.

OPIE: Yeah, that’s for sure. So, you know, because I’ve shared this with you, that the person that I most wanted to photograph who’s no longer with us, that I tried for almost a decade to have sit for me, is Joan Didion.

LACOMBE: Yes.

OPIE: Who have you not been able to photograph that you’re just like, “Ah, I wish I had made that portrait.”?

LACOMBE: Well, I mean, one of them is still possible, and you’ve done it. And obviously Tacita has done it. David Hockney. But there are so many people, Cathy. I just don’t want to fall into a funk thinking about it.

OPIE: Right. When you look at so many photographs of really iconic people, and you often photograph very iconic people, it’s always so interesting to think what you could do. It’s like, “Oh, well, what kind of relationship would I have had with Joan?” That’s the curiosity in me. Because I had been reading her since I was in high school. So, the other thing is just honoring these people that you have so much respect for.

LACOMBE: Yeah. Joan, for example. I was really lucky because I photographed her several times over the years. Sometimes in a reportage way, and sometimes as a proper portrait. But I love that so much about the work that we do, also, is that I love to photograph the same people over and over again over years and years and years. I mean, some people I’ve photographed for like 35 years or some, I’m afraid to say, even more.

OPIE: Yeah.

LACOMBE: And I love that continuous renewed conversation of finding each other, and we make a new portrait of that time in their life and in my life, too. Do you love that, too?

OPIE: Yeah, I love that. There are friends that I have photographed for over 30 years and I love how the body changes. I just think that the body changes with my friends, too. Even the addition of tattoos to their bodies. When you look at a portrait of Pigpen from the early nineties versus a portrait of Pigpen now, the accumulation of the marks on the body are also part of the history. It’s a sweet spot for me.

LACOMBE: Yes. And I’m sure, Cathy, you have many more friends with tattoos than I do.

OPIE: Maybe. [Laughs] So, any other questions?

LACOMBE: I think we have to have breakfast.

OPIE: Well, it’ll be fantastic for the public to see this. And the ICP has done such an amazing job of rebuilding. And I also just want to state that the most important thing about all of this is how grateful and happy we are. That we are privileged, and we do get to bear witness, and we get to have these amazing, wonderful relationships that grow in our lives in all these different ways. And I’m just happy that there’s an exhibition of our work, the three of us, that people will be able to hopefully enjoy and be inspired by.

LACOMBE: Yeah, that’s very well-said. Thank you, Cathy.

OPIE: Thank you, Brigitte.