PANEL

For Artist Diedrick Brackens, Weaving Is An Act of Religion

Essence Harden and Diedrick Brackens, photographed by Deonte Lee / BFA.

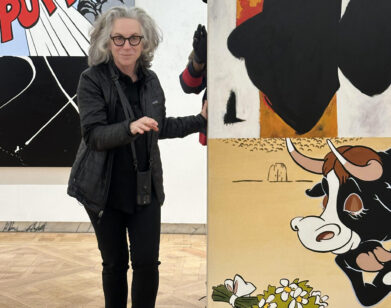

Last week, Diedrick Brackens got together with curator and friend Essence Harden at The Standard Hotel in the East Village to talk about his new exhibition at Jack Shainman, blood compass. Spread across two of the gallery’s locations in Tribeca and Chelsea, the show includes a series of large-scale textiles that map out a fictional place, drawn from the artists own biography, and broader diasporic movements throughout American history. In conversation, Brackens explains why his weaving practice is an act of religion, and the growing proliferation of textiles within the contemporary art world.

———

ESSENCE HARDEN: Hi, everyone. I am really excited to be here today in conversation with Diedrick Brackens on the occasion of his opening at Jack Shainman. It’s a single exhibition across two different locations. To begin, can you talk to us about that decision, and the types of work included in blood compass?

DIEDRICK BRACKENS: Yeah, absolutely. Thank you for agreeing to talk to me. And thank y’all for being here. In part, the show is in two places because it’s been a prolific few years and I’ve been very resistant to having gallery shows back to back. I had my show here almost three years ago, so I had a lot of time to think about where the work was and where I wanted it to go. In that time I had a lot of museum exhibitions, and that opened me up to new ideas and being okay with going deeper. I started to think a lot about how it’s always the same; the place that I’m from, the things that I’ve seen, and I’m taking these historical threads that my own biography touches on and trying to expound that. One of those things for me is the way that black folks have moved through and around this country at various points in time, and then using that journey on this interpersonal level with one or two characters that appear in the weavings. Then thinking about myth, ritual, sacrifice, interiority, joy, all of these things that are sitting in the same box.

HARDEN: Thank you, this is a great introduction to the work. With the Tribeca part of the exhibition, it’s the largest work I’ve seen you make and show publicly. We have blood compass, which is the title of the exhibition and the title piece, which is 22-feet tall. The space is gigantic, and you can see the backs of multiple pieces. So there’s two decisions happening there: One is scaling up by quite a bit, and then looking at the back parts, and I noticed this kind of ghost image happening within the textiles. Can you talk more about those things?

Installation view, Diedrick Brackens, blood compass, 2024. © Diedrick Brackens. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio.

BRACKENS: Well, I think everyone here knows, but I make textiles. I feel like the loom, the practice of weaving brings me into contact with a lot of metaphors that we hear every day. It touches everything. It’s about language, it’s about magic, it’s about time travel, it’s about narrative and storytelling in a particular way. But it’s something that most people do not have a direct relationship to. Everyone who approaches the practice of weaving is always sort of enchanted, and I think about it literally. I think about these weavings as accessing some sort of spiritual technology in the same way that someone who drums thinks of it as medicine, or DJs, et cetera. I didn’t make these weavings knowing that they were going to go into the container at Tribeca. But I feel like they work on the space and the space works on them. They don’t seem like they’re fighting each other. They sit so gracefully in there and it stuns me. But I’m still reckoning with how the two shows relate to each other, because one was birthed at the last minute. I was thinking about this work for an exhibition that was delayed, and then also the dimensions of that space were such that I had the verticality to play with, but now that exhibition’s not happening in that format. I don’t tend to necessarily respond to architecture while practicing. I like living for the work, not living for an assignment. So it seems fortuitous to me.

HARDEN: Absolutely. Part of what you’re moving through is this idea of storytelling and narrative, and drawing upon diasporic movement and your own personal histories. You’re often thinking through prose and other types of writing. I’m thinking about histories that are particular to places in which you or your family’s from, and these broader narratives finding their way into the work.

BRACKENS: I feel like a lot of my instruction in life that was not formal education has been through storytelling and the ways in which I came to understand who my parents were, who my grandparents were, what the place that we were from meant. It was always through story, never a direct transmission of information. I was always presented with the fabulous or the fantastical, even if it was about a mundane life. So through that piecemeal relationship to the people in the place that I was from, I continued with my own questions and finding other things that resonated with that way of living, like Essex Hemphill or Octavia Butler, as you mentioned. Those things started to fill in the gaps where it was like, “This seems very similar to the thing that my family member told me,” or, “This horrific event in this tiny Texas town sounds like something that happened in my tiny Texas town.” So I started being like, “Oh, these things aren’t dissimilar, I’m not disconnected from this. These aren’t isolated events. It’s a larger systemic thing.” I even came to think about the big questions of our country in this very small way and remembered, “Oh, I’ve experienced this. I know what that’s like.” This is a way I can point people to my set of interests or open up a portal for someone to think about what’s happening right now.

flames and familiars, 2023. Cotton and acrylic yarn. 98 x 296 inches (overall). © Diedrick Brackens. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

HARDEN: There’s also this romantic aspect within the work that comes through. I was reading this review from Hilton Als, and he references the Black Romantic Exhibition at the Studio Museum of Harlem. It was like 20 years ago, and it referenced your work. I was like, “Oh yeah, this long tradition of seeing sensuality and desire between black men.” It might feel like a little bit of an aside, but I think it’s part of the storytelling narrative that happens within the visual field for your work. Does this resonate with you, this idea of romanticism happening within the work?

BRACKENS: It makes sense. That’s a good question. There are several things in the practice that are right on the surface for people to see and unpack, but not everyone does. And sometimes I can’t tell if that is because they don’t see it or they would rather talk about it.

HARDEN: Like what?

BRACKENS: Like what you’re asking about the romantic or sensual possibilities. Sometimes they’re right there. There was a series of works at Frieze LA two years ago at my shared booth at Various Small Fires [VSF] with Dyani White Hawk, and it’s a storybook of images where there’s two figures sitting on a bed, and one’s about to touch the other, and it sort of culminates where there is a figure laying on a table and the other figure is eating butt, basically. And everyone’s just like, “Oh, oh, these are so beautiful, they’re just so mournful. There’s something so sorrowful about them.” And I’m like, ” What’s sad here?!” There are these moments where I’m like, “Are people intentionally ignoring the thing? Do they not see it? What are they not experiencing?” Then I have moments where I’m like, “Oh God, this person who I adore is here with their child and they want to take a picture in front of the weird one.” Romanticism is something that I’m always interested in putting in the work, as well as having these bodies in nature, having these bodies outside, because it’s the space that often we imagine black folks as being divorced or dispossessed from. And for me, I’m like, “Oh, I am from a rural context.” I did not really know the idea of what a city really was until I was an adult. And the outdoors, writ large, is a space where a lot of queer folks find themselves, or can be themselves, or participate in spaces for desire or sensuality and all of these things that you described. So trying to couple those things feels important.

untitled flag, 2022. cotton yarn. 142 x 18 1/2 inches. © Diedrick Brackens. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio.

HARDEN: That makes a lot of sense, in part because you’re from Texas but you went to college in California. Black folks in the West have a different relationship to the outside, and it’s really present in the work. There’s this other thing about back of the work being shown. This is not something that’s generally done by you or other people who work in textile, and I wonder why you made that decision, and also the kind of formality behind creating a weaving around what is viewable space, what is acknowledged space within the weaving itself. You already fight back against various techniques and you don’t trim the work.

BRACKENS: Yeah. Some of it is in tandem with the space, that there are a few walls to mount work to, and a lot of it was from very exciting conversation. Hanging a show with Jack is hanging a show with Jack, meaning the man himself is there in the space making decisions, talking through the work. That has been really exciting, to have someone who cares and thinks about how the things interrelate. I like for people to see the backs of the works because even if they don’t weave or have any sense of it, seeing both sides allows people to understand the construction a little bit more. Oftentimes the figures don’t show up on the back, they don’t register at all. So it’s almost like seeing the landscapes without the people in them and then seeing the landscapes with the people. So there’s this interesting flip to me. There’s some technical stuff that happens that people who do weave know. It’s like a moment to brag or to be like, “The back of this is clean as the front. Y’all need to see that I know what I’m doing.” For me it’s almost a moment to be like, “I know how to do it. I am technically accomplished.” Even based on the figures disappearing, there’s things that happen on the back that wildly surprise me. There are these sort of ghosts or fugitive images that aren’t what is woven into the front. You can sort of Rorschach them, a little bit. So there’s this emotional register to being able to see the back, as well as giving the viewer even more information, more access.

HARDEN: The first time I saw the back of your work was years ago, but I was like, “Why?” And you were like, “Why don’t we do that?” And here we are now. We were talking earlier about the landscape of textile and the education that’s happening or not happening with that. What does the next 10 or 20 years look like for people going to school for weaving or not, if there aren’t people leading the next generation and cohorts of students? What does it look like to create a vision for folks to follow in those footsteps?

towards the greenest place on earth, 2023. cotton and acrylic yarn. 83 x 83 inches. © Diedrick Brackens. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio.

BRACKENS: That’s another great question. For a long time I’ve had a lot of anxiety about what it should look like. I think a lot of the textile/fiber folks that I know are very interested in gatekeeping. Like, “This is our thing. We don’t want anyone else to do it. Who taught them to weave? How good are they at it? They don’t know this and this and this.” I’m less interested in that, because I was educated right in the middle of a contemporary art craft world where those boundaries are now starting to fall apart. But I do worry about the people who want to learn, but they don’t have a person or a place to do so or to sharpen their ideas around the discourse. I love that textile ideas and languages and materials are infecting contemporary art right now. You cannot walk into a gallery in any major city and not see a show that has some sort of textile-inspired work, which is really wonderful for the medium.

But as someone who weaves, I have a stake. I am dedicated to the idea that people can learn, will learn, and will continue to weave in whatever spaces, whether it’s academic or not. I’m going back into the classroom in the fall to teach people how to weave, which I’m really excited about. I’ve had a lot of conversations where people are like, “Oh my God, you’re going to teach? It’s going to take you out of the studio.” But the studio is everywhere. Weaving with 30 other people who want to learn that discipline keeps it growing, and it keeps me sharp and excited. I can vividly remember the moment where I was like, “This is what I’m going to do.” And when you see someone else have that moment, you’re like, “Oh my God.” To be that model for people is really exciting. I feel like you can count on one hand the times you’ve had that moment with someone who was showing you how to live. That’s magical.

HARDEN: It’s really magical. You spoke earlier about ritual, and I think with this body of work itself, there’s this kind of investment in the hours which are kept around ritual. It comes up in the hues that you use in the textile. And this is the idea of silhouettes and how that then operates within sort of narrative overall of blood compass. And it has a African diasporic lens into your work that it is this investment in the acts of ritual as well. I wanted you to talk more specifically about that.

BRACKENS: Damn. I feel like weaving is the only ritual I keep. Even if I’m like, “I should meditate. I should do this,” I’m like, “I’ll do it at the loom.” Ritual in some sense is about repetition, and repetition is a holy act. To repeat something over and over is to manifest it, to make it real. Every inch of weaving that I do materializes this magical, mythic, fantastic space that I’m building. While I don’t imagine most of those images can be made real, hopefully I’m manifesting some sort of real version of that space, whether it be about the community that I’m building, or the traumatic stories that I’m telling that are being transformed. I can’t get too deep into the Southern Baptist bag, but I feel like I am the Bible made flesh. Every time I say something, I’m like, “Oh God, I sound like my grandma.” Even in the studio, I’ll have meetings with the team and they will pare it back to me, and the things that I say always have something to do with church or the Bible. So it is a space where I can let out the lapsed Baptist a little bit and re-engage with those rituals and try to rehab them to something that looks more like my reality.

HARDEN: That’s great. Thank you.

the forks of the creek, 2023. cotton and acrylic yarn. © Diedrick Brackens. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio.