Farhad Moshiri Floats On

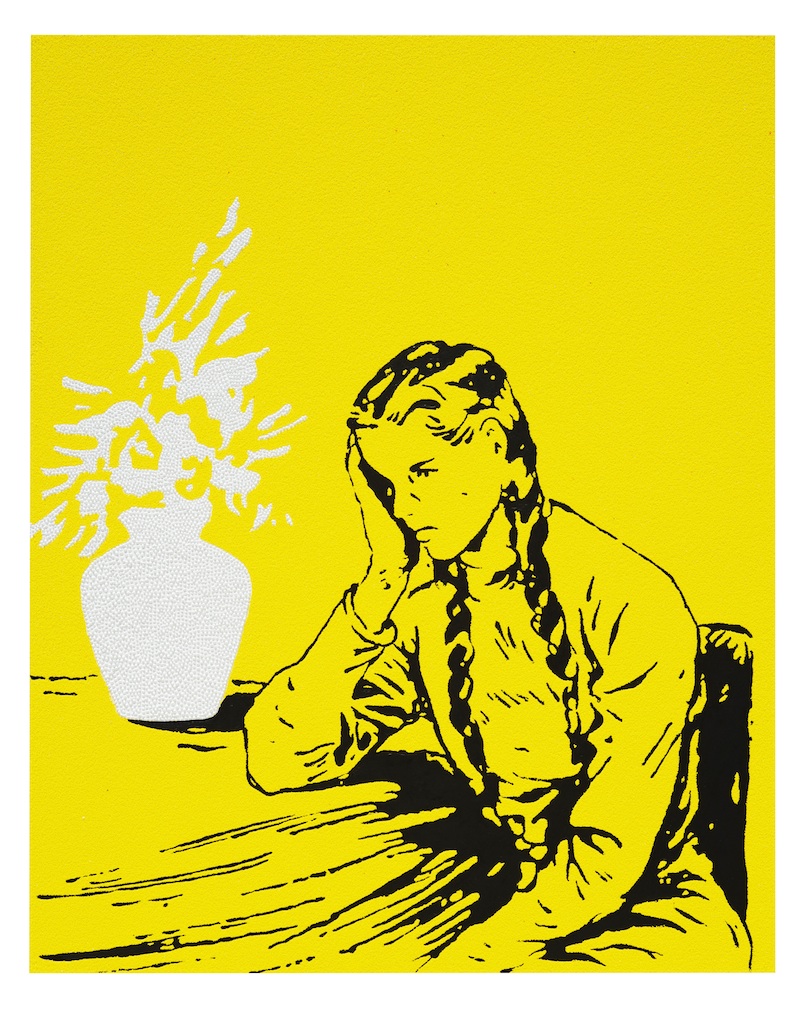

Merging the East and West, both literally and conceptually, Galerie Perrotin, New York presents “Float,” its first solo exhibition of Iranian artist Farhad Moshiri. Moshiri, whose paintings have been exhibited internationally since 1989, draws from highbrow and lowbrow culture as well as his Iranian heritage and American education.

Moshiri was born and raised in Shiraz, Iran. In the mid-’80s, he attended the California Institute of the Arts, where he encountered artists such as Michael Asher, John Baldessari, and Don Buchla. Now the artist lives and works between Paris and Tehran, drawing inspiration from anything and everything, including pop and conceptual art, comic books, classical portraiture, and religious iconography.

His newest paintings, all of which are on view in the exhibition, often use puns to convey deeper messages beneath the pop-like imagery. Take, for example, Travelers, a black-and-white painting with beads embroidered on canvas that depicts two lions. Through pastel blue and yellow speech bubbles, the lions say, “I wish we could travel,” and, “If we had a credit card we could travel the world,” in Persian script. Here, Moshiri engages the viewer through language and comments on globalization and commodification, albeit with a humorous tone. Prior to the opening of “Float,” we asked Moshiri about his influences, formative memories, and creative processes.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: You clearly present Iranian and Western themes throughout your work. What are some of the most influential topics within Western and Eastern cultures for you?

FARHAD MOSHIRI: I’d have to say megalomania, its roots and branches. Within that topic in both cultures, there are shitloads of aesthetic oddities that tickle my imagination. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, there’s a general fascination with Baroque house furnishings, but not the real things, because those would be old and used. It must be newly manufactured, and therefore, fake is more desirable than real. To top it off, every valuable object has a plastic cover, sometimes even plastic wrap! Another example is an expensive carpet that ends up being too big for the living room so it runs up the wall at one end. This is contemporary art, man!

MCDERMOTT: Aside from pop art and other obvious references, where do you draw inspiration?

MOSHIRI: Artists are hungry predators. Anything is game. You might suddenly catch something from the side of your eye while stuck in a traffic jam, or better yet, something could be flashing right before your eyes. I once saw a phrase in the form of cutout stickers on the side of a travel bus that said, “I go to trip, good bay.” Not “goodbye,” but “good bay.” It’s delightful to see broken English used in such a playful way. Another sentence I saw on the back of a truck was “I forget you forever!” It was a phrase and lost in translation from Farsi to English, but super emotional, so I had to use it in a work, although I’m pretty sure the driver wanted to say something cheesy like, “I will never forget you.”

MCDERMOTT: Can you talk about one extremely formative moment for you as an artist while living in Iran?

MOSHIRI: About a decade ago, my wife found a rusty old icing set—a rather large syringe with various cone-shaped tips used for cake decoration—from the ’60s in a trunk that belonged to her aunt. When I saw it, it was as if I’d seen a magic brush. It doesn’t sound exciting, but you have to understand the context in which it was found. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, lots of newlyweds made babies. When this generation grew up and started getting married, a culture developed that was very eye-catching and coincided with my stumbling upon the icing set. It was an absolutely enlightening find. It was the ultimate tool of the period to paint with. I would pour acrylic paint in one end, squeeze it, and happiness would come out the other end.

MCDERMOTT: Can you talk about another formative moment for you as an artist, but while living in L.A. or Paris?

MOSHIRI: When I was in college at California Institute of the Arts, CDs were not yet invented and VHS was the norm, [but] suddenly, out of the blue, sampling was invented. This meant one could digitally capture a chunk of any sound and use it as an instrument on a keyboard. I was into sound synthesis, but the idea also translated into the usage of imagery so smoothly. The thought that the whole world is up for grabs and that one can simply borrow and transform anything into one’s own was, and is, creatively empowering. I am still running on the buzz from those days.

MCDERMOTT: So referencing your new works and show, what does “Float” mean to you?

MOSHIRI: Finding a series of new ideas and finding a title to go with it is supposedly a natural and fun activity for artists, but sometimes it turns into a worrisome affair for me. When my gallery kept asking how I was doing with new works and I hadn’t even started, I kept thinking of what to say. All I could say for a while was that I have some ideas floating in my head and “Float” just stuck. “Yes! ‘Float’ is the title,” I said. Just like that. I think it works well. Actually, I love it.

MCDERMOTT: Tell me about your creative process—from conceptualization to production, what is the process like?

MOSHIRI: Finding ideas has become more and more difficult. Sometimes seasons go by and I find nothing that I feel passionately about. I helplessly and desperately pray for sheer good fortune to find something. But let’s say I do find it—then I need to see it, so I create it digitally to make sure it works. If it lends itself to embroidery, I hand it over to a team of embroiderers who take four to eight months to finish a piece. Meanwhile, I am working on other materials that need personal attention, like oils and acrylics. The embroiderers work at home so I see the works once a month or so. My own atmosphere is messy and unorganized. Once a work is finished, it is crated and shipped off before getting damaged in the studio. I never have finished works in my studio that collectors can view.

MCDERMOTT: Do you notice differences in how your work is received in the East opposed to the West?

MOSHIRI: Some of my earlier found-object installations that I did in gold leaf were not taken seriously by Iranian viewers because they thought they had seen stuff like that in their grandmothers’ houses before. Some of my later works, which came with a lot of irony and cynicism, were also a bit hard to digest. Most people, however, appreciated the more emotional pieces. In the West, I thought my works were initially judged with some preconceived notions due to me being Iranian. I felt condescension at times.

MCDERMOTT: If you had to describe your work to someone who had never seen it, what would you say?

MOSHIRI: I absolutely hate situations like this. I always think to myself, “I’ve been producing images all my life and still I have to explain myself from scratch.” Thank god I have done my knife installations. One evening a while back, I was introduced to Pierre Cardin at Maxim’s in Paris and he asked, “And what do you do?” I quickly said, “I stick knives into walls.” As he passed by he said, “Do you know Fontana?” I didn’t have enough time to tell him, “Yes, but it’s not quite the same thing.”

MCDERMOTT: How would you define your philosophy toward art?

MOSHIRI: It should challenge any preexisting definition of art.

“FLOAT” IS ON VIEW AT GALERIE PERROTIN, NEW YORK THROUGH OCTOBER 4.