Thoroughly Modern Steichen

Tomorrow brings the opening of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibit “Edward Steichen in the 1920s and 1930s: A Recent Acquisition,” which hosts a variety of 42 gelatin silver prints from the two decades that Steichen worked as Conde Nast’s chief photographer. Similar to the current awakening of digital technology in art and advertising, Steichen made photography famous with his portraits of the likes of Winston Churchill, Eugene O’Neill, and Charlie Chaplin; fashion and commercial spreads; dynamic still lifes (see: An Apple, A Boulder, A Mountain, France); and horticultural close-ups. Steichen’s career also spanned a range of titles, from painter to aerial photographer in World War I to curator to head of the U.S. naval photographic division in World War II to director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. A central modernist figure (friend Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column was installed in Steichen’s garden in Boulanger until he moved back to New York) who initiated the first US exhibitions for artists like Matisse, Steichen was well known among artistic circles and readers of Vogue and Vanity Fair alike.

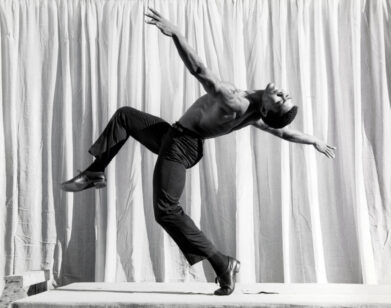

The photos from these two decades show his shift from pictorial romanticism, perhaps left over from his painterly pursuits pre-World War I, to a simple, direct modernist eye. Senior curatorial assistant Carrie Springer elaborates, “I actually see hints of romanticism in most of what he photographed, but there is much more of a modern clarity. In his portraits of artists and actors, there is a sense of drama, but because he [knew] how to make a compelling picture with highly interesting visual elements.”

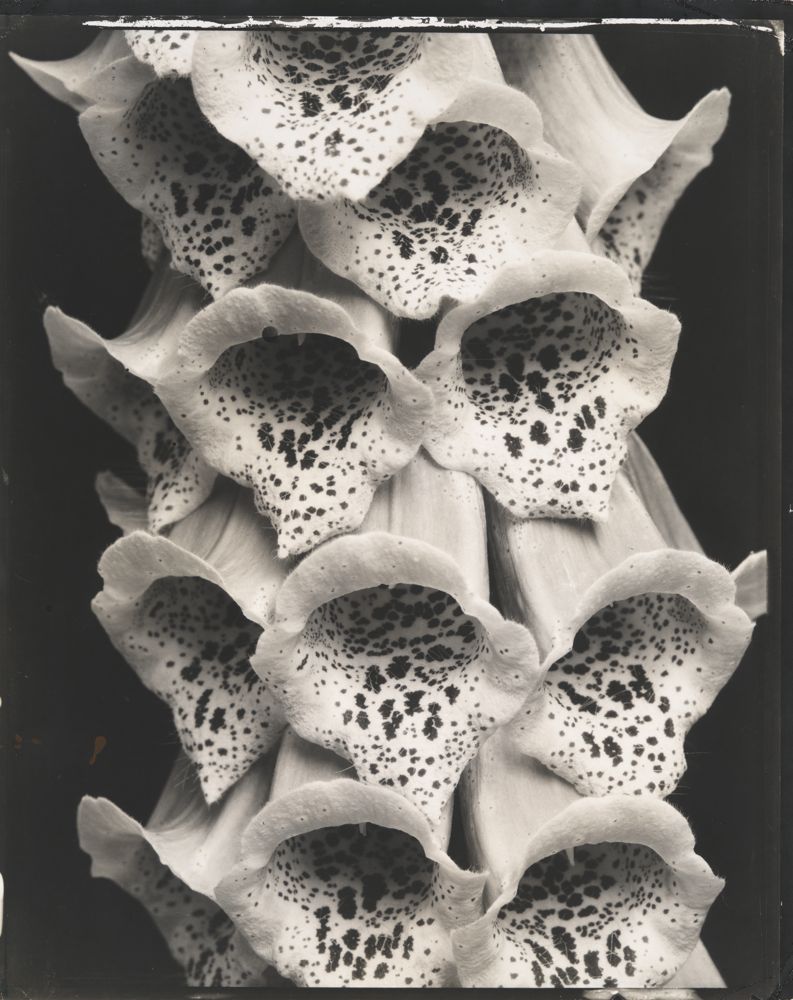

Even more than Steichen’s portraits, which capture the kind of revealing candor found in split-second shifts of expression, his images of natural subjects quietly shatter convention by highlighting their stark, mysterious, alien-like perfection—an eroticism of unrecognizable familiarity that also shaped his commercial campaigns for towels or silverware. Springer explains, “He used lighting to create these kind of abstract environments for his subjects—in our show, there’s a portrait of Maurice Chevalier dancing while holding his hat, but the shadows of him and his arm look like they’re almost dancing in these abstract forms. The focus is very much on him and his face, yet it’s all constructed in a very modernist environment.”

While promotion of cultural consumption was second to Steichen’s artistic vision, the camera’s prolific potential encouraged a mass appetite that was later itself thrown up critically in Pop art. As Springer explains, “I think he was interested in the fact that magazines could reach a large audience, and that they were something people could afford to buy—not unlike selling a photograph to be put on someone’s wall.” However, Steichen’s earnest appreciation of creative talent dates him as a man of his own pre-celebrity obsessed time. “I don’t know if he was fascinated by celebrity,” Springer says, “but I think he may have had a natural inclination towards highly creative people, and those were the people who also tended to be in the cultural limelight. He himself was to a certain extent. I don’t think he inserted himself in his images in any way, but there was a sense of the photographer as celebrity.”

“EDWARD STEICHEN IN THE 1920S AND 1930S: A RECENT ACQUISITION” OPENS TOMORROW, DECEMBER 6, AT THE WHITNEY MUSEUM AND IS ON VIEW THROUGH FEBRUARY 23.