Ed Ruscha

Monotony and the horizontal go hand in hand. You throw a vertical in and it’s disruptive. It’s like a brick wall. It stands up and you run into it. I always liked horizontals. Horizontals to me were like landscapes. Ed Ruscha

Like dreams or myths, Ed Ruscha’s paintings are both heroically expansive and irreducibly straightforward. It’s a rare kind of master who can do so much to define the practice of painting while resisting all of its comfortable cues and codes. The 78-year-old Angeleno by way of Oklahoma isn’t a figurative painter—even if mountains and gas stations do appear on his canvases. Nor is he an abstractionist, although swathes of uninterrupted color do take on a charged materiality. Single words or curious phrases often float spectrally across his works, yet without the heavy-handed, cerebral cool of conceptualism or the winking public appeal of pop; rather, like potential conduits, the word pieces seem to burrow into the synapse between objective signifier and subjective meaning. Ruscha is more like a sign painter turned alchemist, and the most fitting classification is probably landscape artist. His bold horizontal paintings often possess the aura of horizon lines, not to mention the fact that the artist has also serially photographed gas stations, swimming pools, and even the entire length of city streets. Whether Ruscha likes it or not, his strongest association is to the West–to Southern California, to the dark, golden dreams of Los Angeles, to the grand, cinematic emptiness and possibility of Hollywood. After all, in a primarily eastern-leaning art world, Ruscha’s Pacific Coast career has been an anomaly, especially given the fact that he is arguably the most important American artist alive. Looking at Ruscha’s work is a lot like conjuring the vastness and tragedy and aspiration of America, a lonely and unlimited universe.

San Francisco’s de Young Museum is currently probing that very connection in its show “Ed Ruscha and the Great American West.” In 99 works, ranging from enormous oil paintings to photography, lithographs, and archive publications, the exhibition charts Ruscha’s ongoing fascination with the themes and symbols of western expansion—from his iconic 1977 back of the Hollywood sign and his documentary shots of buildings on the Sunset Strip to his series of acrylic works pronouncing “The End.” Ruscha is something of an enigmatic cowboy haunting those horizons—or maybe he’s a pioneer. Sterling Ruby, another idiosyncratic, L.A.-based artist, went to Ruscha’s studio in Culver City to discuss how the artist got here. —Christopher Bollen

STERLING RUBY: I thought I’d start off with a question about the de Young Museum show. They were kind enough to send me the press statement for it, and I wanted to read something in it about your work that comes up a lot. I hope you don’t mind me reading it.

ED RUSCHA: Not at all.

RUBY: “In 1956, at the age of 18, Ruscha left his home in Oklahoma and drove a 1950 Ford sedan to Los Angeles, where he hoped to attend art school.” This journey of yours is now a legend. A lot of people refer to this drive west when discussing your work and have even offered it as the catalyst for your entire career. I was wondering if you could talk about growing up in Oklahoma and your interests in art, and what drove you out to L.A. as opposed to New York?

RUSCHA: I was born in Omaha and moved to Oklahoma at about age 5. I was raised Catholic and they kept me tied to the church. I had to go to mass all the time and do all that. And then they wanted me to go to a Catholic school, so I did that for one year and didn’t fit in so well. I ended up going to public school and that worked out okay. I was fine with that.

RUBY: That was a better fit for you?

RUSCHA: I’m not saying I got much of an education out of it. It was okay. But then in the meantime, I had to take catechism lessons on Saturday mornings because my dad was thinking that I might be straying from the church. And we traveled with the family out here to California a few times, and we’d go to Northern California to see my grandfolks. I came through L.A. a couple of times as a kid, and I always liked it out here. I just remember the vegetation and the chicks in cars, that sort of thing. It was real swanky compared to Oklahoma. And when it was time to leave for college, I had a choice. I knew about Pratt in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, Kansas City Art Institute, and ArtCenter here in L.A. And there was also this school in L.A. called Chouinard. I really thought I wanted to be a sign painter. So I thought ArtCenter might be the place to go. They favored industrial design and commercial art. They had fine arts courses, but it was mostly commercial art and industrial design. Car design was really big. Automotive design.

RUBY: It still is. ArtCenter is one of the biggest schools in America for car design.

RUSCHA: It was kind of unplanned. I arrived here and went to visit the school, and they said there were no openings. I had a quasi-portfolio from high school art classes, but I couldn’t get in there. So I went right over to Chouinard and hooked up there and started going. I remember at the time ArtCenter had a dress code, too. [Ruby laughs] You couldn’t have any affectations of a beatnik or facial hair.

RUBY: No goatees?

RUSCHA: No students had facial hair. And no berets. No thong sandals. No bongo drums. None of that stuff. I thought that was weird. At Chouinard you could do anything you wanted. You could go to school naked if you wanted to. I liked it for that. And they had commercial classes. I took an advertising course, a design course, a lettering course, drawing—basic courses. And there was one called Visual World, which was kind of a science class almost, about the concept of vision. It was good. The people I ended up going to school with were all kind of competitive, and there were about five of us all from Oklahoma.

RUBY: Really?

RUSCHA: Yeah. Joe Goode is a longtime friend. And I came out here with my friend Mason Williams, who was a songwriter. He wanted to go to actuary school or something and didn’t go to art school. But the other guys in school from Oklahoma all hung out, and we rented houses together over in Hollywood. The instructors at the school were good, but I think I got more from the students, especially in that kind of competitive atmosphere. People were really serious. It was still all loose and beatnik-y, and you could do almost anything you wanted—smoke in classes and all that. But at the same time I had to unlearn all the things I was taught growing up. I wasn’t as close to my father as I was to my mother. She encouraged me. My dad said, “Do something practical. You got to do something to make a living. Don’t go to art school just for the ivory tower of it.” That was until he reads this story in his favorite magazine, The Saturday Evening Post. There was this story about Walt Disney, and it tells how he was a friend of Nellie Chouinard and he financially backed her school. So my dad was all for it. He said, “If it’s good enough for Walt Disney, it’s good enough for my son.”

RUBY: When did Chouinard switch to CalArts?

RUSCHA: I went there for about three or four years. In the ’60s, it began to morph into CalArts.

RUBY: Did you have any interaction with the students from ArtCenter?

RUSCHA: No. I did get a gig later to go over there as a visiting artist. I went and talked for two days. This was back in the mid-’70s. Someone gave me a pill called Desbutal. They said, “take one of these, you’ll feel good.” So I popped one, and what it does is it kills your appetite and makes you want to talk. So I was good with that.

RUBY: Was the L.A. you had experienced as a kid different from the one you found when you arrived as an adult?

RUSCHA: Yeah. I recall coming over the hill while driving and looking down into L.A. I was reading an article in a magazine that said there are a thousand people a day coming into this city, net gain, and I just thought, “That’s astounding.” And it’s considerably more today.

RUBY: Astounding that L.A. would attract that many people on a daily basis?

RUSCHA: Yeah. And that was in 1956. The whole place was like a scratchy black-and-white movie. There were a lot of charming things about L.A. and a lot of aggressive things about it. And it all just made up this new campus for me, and I began to feel real good here and glad I didn’t go to New York. New York kind of discouraged me back then because it was so cool, you know—cold. I was tired of cold winters and I thought, “I’ll go more tropical. I’ll go to L.A.” But it was unplanned. It was a shot in the dark. I came out and moved into a boardinghouse down near Lafayette Park. I didn’t have a car because I sold the one I drove. And it didn’t seem like I even needed a car for three or four years because there were streetcars. I always hopped a streetcar. And one of the guys from Oklahoma had a brand new ’57 Chevy convertible.

RUBY: Oh, nice.

RUSCHA: Yeah, that was great. He drove us all over. And I liked the jazz scene going on here. They had jazz clubs all over the place. But mostly I was busy doing school stuff. I kind of checked out of everyday popular culture. I didn’t watch TV. When one of us got a TV, we were constantly taking it to a pawn shop. [Ruby laughs] We never got to watch it because we were pawning it for the next meal or two.

RUBY: I want to ask what a horizon represents for you.

I think the most interesting stuff comes from people who’ve just got nothing to lose. You know, let’s kamikaze this thing—just throw themselves in it, devil may care. Ed Ruscha

RUSCHA: I started seeing it when I was driving. And there was something monotonous about it. Monotony and the horizontal go hand in hand. You throw a vertical in and it’s disruptive. It’s like a brick wall. It stands up and you run into it. I always liked horizontals. Horizontals to me were like landscapes. And I also got it from seeing movies as a kid. Eventually they began to stretch the screen size so that it became Panavistic—they kept making it wider and wider. So I’ve found myself making paintings wider. I like the idea of trying to capture the whole thing or giving you more and more and more and more. Where does it stop? Nobody knows.

RUBY: A lot of the paintings in the de Young show are these kind of elongated, very formal, cinematic works. They read in a formal arrangement of left to right and right to left.

RUSCHA: Yeah. The paintings make up a kind of stage set for some drama or some pictorial element that is in the front of it. If it’s not words, it’s some kind of object. But a lot of landscapes to me are anonymous. They can almost be interchangeable. Like mountains or dry ground that goes on forever.

RUBY: I grew up in rural Pennsylvania. And my family felt that it was absolutely necessary to know how to work on cars. It was just part of growing up. I think I learned how to change the oil before I lost all of my baby teeth. It was my grandfather just standing over me. But I never really became a car person. I never got obsessed with makes or models. I always thought of cars as necessary, as a kind of utilitarian device to get away. I was curious, are you focused on makes and models, or do cars have a more abstract representation within the context of your work?

RUSCHA: Well, maybe in high school, I started noticing that stuff. There was Hot Rod magazine. And after the war especially, there seemed to be a resurgence of interest in taking an old car and modifying it or hot-rodding it—customizing it. I loved that idea, but I didn’t particularly want to do that work myself. And the freedom of a car was absolute. It actually loosens you up to be able to do anything you wanted to do. You could get away from the house and make tracks. So cars to me were always like that. I got into the psychology of cars. I bought this 1950 Ford four-door sedan and drove it for a year or so. And then I kept seeing this 1948 Cadillac convertible. The guy always drove it with the top down. And one day I saw a for-sale sign on it. Oh boy, I thought it’d be nice to have that Cadillac convertible. I talked it over with friends. They said, “Never, never go back in years. You have a ’50; you don’t want to go back to ’48.” They somehow convinced me it was a bad idea. They’re right. You don’t want to go back in years. [laughs] So I didn’t buy the Cadillac. But I eventually got a bunch of cars. I bought a ’39 Ford in 1959 up on Los Feliz Boulevard that I still have in my backyard. I tried to sell that over the years but was never able to. So I just kept it. I have a variety of cars. It’s an ongoing thing for me.

RUBY: What was that one I saw out in front of the studio here?

RUSCHA: Oh, that is owned and lived in part-time by this metalworker named Harley. He restored my truck out in the backyard. He’s an ace metal worker and a recovering alcoholic. That’s his grandfather’s car. It’s a ’49 Oldsmobile. He lives in it when he’s not living up at the Veterans Administration.

RUBY: It has a Remo drumhead in the window to block the sun. I was once visiting Billy Al [Bengston] and Wendy, who I know are good friends of yours. And there was a portrait of you outside their kitchen on a poster for an exhibition. Billy said, “Hey, there’s Ed.” And he commented on how handsome you are and how fitting it was that you were an L.A. artist because you had real movie-star quality. [laughs]

RUSCHA: Coming from him, that’s funny!

RUBY: Do you like getting your portrait taken? Or have you seen it as part of your work over the years?

RUSCHA: I haven’t said no to it, but I don’t particularly enjoy it. It’s a phenomenon of 20th and 21st century life, I guess—pictures and photographs, and everybody’s part of it.

RUBY: I’d like to talk a little bit about the work. For me, your work represents the perfect balance of the apocalypse and serenity. It’s almost like it’s symbolizing some sort of dichotic meditation on existence. Do you think that’s a wrong reading?

RUSCHA: I guess I’m a cynic and am able to spot the dark sides of life and of where I am in the whole swim of things and this city. In terms of the city representing whatever it does, I always thought, “What do you do out here? You chase rainbows.” I see the positives but I also see the dark side. I don’t mind commenting on it either. I’m not directly attempting to communicate with a political stance or a philosophical stance. These things just come to me, and I feel like I’ve got to hammer them out in stone and make them official by getting them down. So I guess that’s why I got into words in that particular way. Some of the words might represent unfriendly things, or less positive things, in the world. I don’t have any control over that because it’s just the accumulation of all the work that I do. It adds up and it ends up being some sort of gumbo, a gumbo of gravel. It’s real granular. And there’s all kinds of little wild things that fall in there and become part of my work. I just kind of monitor it that way, but I don’t sit down and write my own history.

RUBY: I’ve always loved the mantralike sequence of looking at your work in books, particularly in terms of its seriality and repetition. And it’s not only a formal or visual thing; I’m also reading it as I’m looking at it. As you put together an exhibition like the one at de Young, do these themes or repetitions occur to you?

RUSCHA: This show came to me through Karin Breuer, who curated the show for the de Young. It was her notion to do something like this show maybe two years ago. And I’m not one to drop everything and go to work on a show of things that are behind me. So I’m aware of someone making a story of the work that I’ve done before. I don’t participate in the thing as much as I probably should. She had a format and general concept in mind, and I just let her go with it. I didn’t participate that deeply in her choices. But when she finally presented me with the list of her choices, I was all right with it.

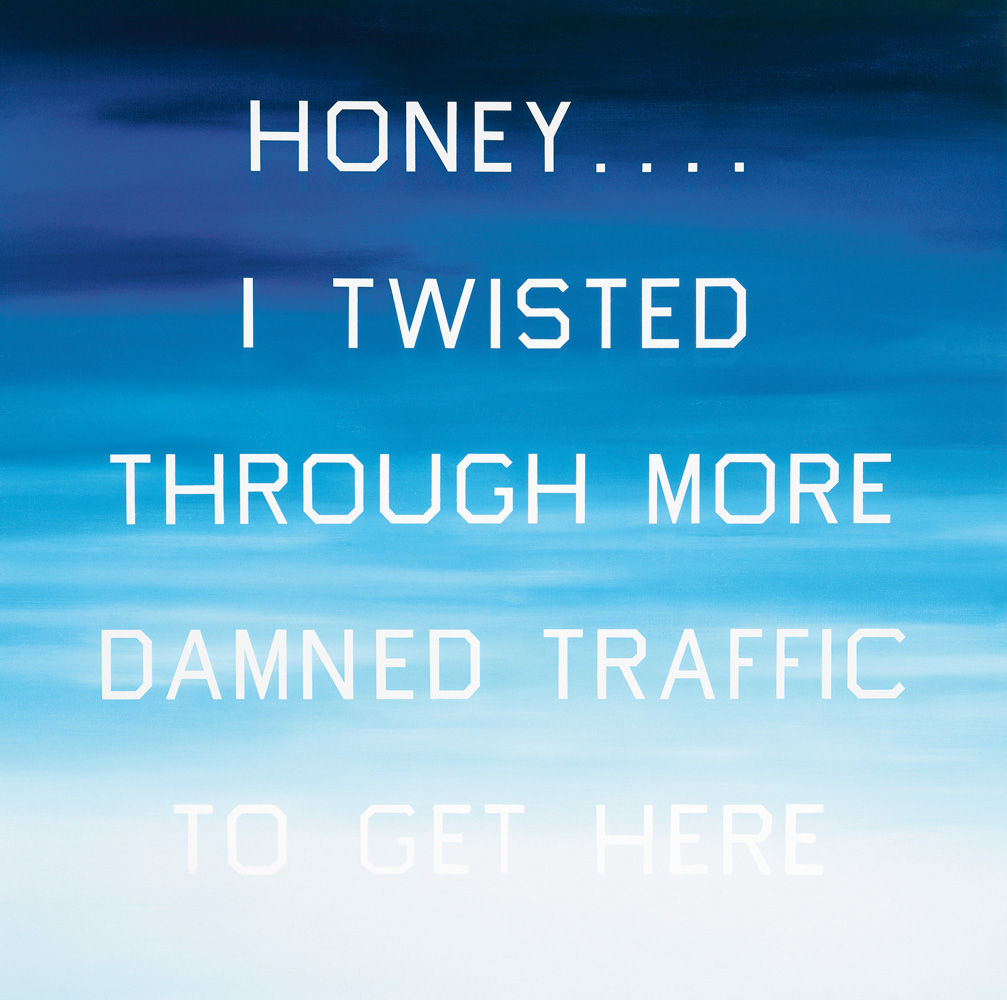

RUBY: Let’s talk about the Boy Scout Utility Modern font [a font Ruscha created and has used repeatedly in his work]. I was wondering if you could explain how you designed it? Did you use tape? Was it an airbrush stencil motif?

RUSCHA: I’ve always kind of felt that it’s able to be manipulated according to how I feel at the time. It’s like some kind of stiff figure in clumsy clothes. It came about through my idea that if somebody who worked for the telephone company were asked to design a poster for a picnic, that’s the kind of design they would come up with. It was a matter of not too much thought given to the history of typography or letter-making but more ad hoc world of “Let’s get this poster designed.”

RUBY: Is there a system for how the words are executed on canvas?

RUSCHA: They all come about through tricks and devices and stencils and block-outs and stuff like that. I don’t have any exact formula that I follow religiously. It varies from moment to moment. But I’ve got a few techniques down. I don’t want to overthink them, and sometimes they’re under-thought. [both laugh]

RUBY: You once said in an interview that being in Los Angeles has had little or no effect on your work. Do you still feel that way?

RUSCHA: I would rather say that I have to be not from Los Angeles but from America. When I go to Europe or Asia, I find myself disoriented. I’m not so inspired by their culture as much. It’s not going to really come out in my work. I would be more influenced by what somebody from America does—like a sign painter from Pennsylvania. It’s not particularly a California thing, although this is the place I spend most of my time, and there are a lot of things here that might translate into my work. But they can happen other places too. I don’t use this as a fountain of inspiration. It comes from all over America.

RUBY: Yeah, I like that. Your first solo show opened at Ferus Gallery in 1963. Who was there at the opening, and what was the experience like?

RUSCHA: I had a group of pals who were also becoming artists in their own way. And we all just felt like there’s no real future in this thing, that you couldn’t make a living off of it. So I would do sign painting. And actually I worked only a few blocks away from right here at Christmas time; I would hand-letter children’s names on gift items for August, September, October, November, to the end part of Christmas. And I’d make enough to live the rest of the year on it. I never expected to sell my art. It wasn’t like today where you come out of art school and they promise you a future. Now it’s almost regulated in a way. When we came out of school, we just wanted to make art that’d blow your hair back and do it for sport. There was no commercial possibility that we saw. Although we heard that some artists were selling their work and that there was such a thing as an art collector. There was this guy named Vincent Price, who was an actor, and he collected art, but he barely got into contemporary art. And there were maybe two or three other people, an actor named Sterling Holloway who collected contemporary art and bought some of Billy Al’s work, and Bob Irwin, and John Altoon, and Larry Bell. So the opening was great because there was a little bit of social juice to it. People came, everyone liked openings, and they smoked and drank. And Billy Al and Joe Goode were there. And all these people were there because they belonged to the gallery. And I met Dennis Hopper there. He’s one of the first people who bought my art. He bought this Standard station painting that I did [Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, 1963]. I was really surprised about that. There was a woman from Seattle who actually bought my first work. I don’t know how that came about, but she was into the contemporary art world. She bought my first actual painting, and I was stunned that I got 400 bucks for it. Well, I had to split that in half with the gallery.

RUBY: Yeah, that’s always the take. [laughs]

RUSCHA: Yeah. But it was up and running. It was fun. Barney’s Beanery was the place that everybody hung out. That was the sort of social place for artists, and there would be a Monday night pilgrimage of people coming down to La Cienega Boulevard. There were three or four galleries there that were interesting—Ferus being one of them. So people would walk between those galleries, and then they’d walk up the street to Barney’s, and that’s where all the fun would start. Ed Kienholz was there, John Altoon, Ed Moses. There was a regular social thing that made it all worthwhile. So we didn’t feel like outcasts on the frontier. We felt like maybe we were becoming part of the city.

RUBY: That you’re making your own scene.

RUSCHA: Yeah. And that seemed to satisfy us.

RUBY: What artists are you looking at now?

RUSCHA: Just about every artist that comes across my field of vision. There’s a lot to take in. When I first started committing myself to making art, there were, like, half-a-dozen people. And then there was the city of New York, which was the center-point of everything, like abstract expressionism. And those people were doing beautiful paintings.

RUBY: And then you started looking at Lichtenstein?

RUSCHA: Then we saw a counterculture, a new thing happening with Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg and those people coming after that. They seemed to be working on something that jumped generations, like they were influenced by people working at the turn of the century and Kurt Schwitters and people who were doing things like that. But, anyway, there’s so much going on today. I continually hear, sometimes from artists, that everything’s done. It’s been done. I fail to see that.

RUBY: I’ve always felt like, particularly in the ’90s with all of the simulacra—speak of art being only a repetition, that it was kind of bullshit. And in fact, it was something to work against. And I think you’re right. I’m still amazed that after all the talk of painting being dead and art being only about the market, that there’s still very interesting things being done.

RUSCHA: Oh, yeah. I think the most interesting stuff comes from people who’ve just got nothing to lose. You know, let’s kamikaze this thing—just throw themselves in it, devil may care. That’s a lot of abstract painters. They seem to be doing everything all at once now. And so these different styles are jibing and not so jibing, and they’re clashing. But they all seem to be working in their own domain. Whereas back in the ’60s, man, it was kind of a dull world. It was a vital world. But it was kind of contained and not too recognized by the public. Now art is absolutely recognized by the public.

RUBY: It’s so much different today. You have an orchard going in the back of your studio. What specific fruit trees do you have out there?

RUSCHA: I’ve got a couple of blood oranges. And I’ve got a Meyer lemon tree, a Mexican lime, and a tangelo tree. I’ve got two grapefruits. I went to this place out in the Valley called Boething Treeland Farms. Do you know that place?

RUBY: Yeah. They do a lot of grafting of hybrid trees.

RUSCHA: Yeah. I got a lot of those. I remember visiting a guy out in Riverside who had a bunch of grapefruit trees. He just loaded me up with these grapefruits. They’re the greatest grapefruits I’ve ever had in my life. And I told him after I tried these grapefruits, “I’m saving these seeds to grow grapefruit trees.” And he said, “It doesn’t work that way. You can’t grow it from a seed. You’re not going to get fruit for eight years. You have to have a grafted tree to make it work.”

RUBY: That’s exactly right.

RUSCHA: So these are all graft trees. You can see it from the scion, from the trunk of the tree. So I got a little quick lesson on that. I’ve got three avocados back there and two cherry trees and a pomegranate, a fig, and a peach tree. I’ve got one apple tree that has five different kinds of apples on it. They’re all grafted together. So it’s been fun to do that. I’m worried about this insect that brings mold; it’s called greening disease. If it gets on your tree, it’s dead. It’s already hit the state of Florida. It actually exists out here too, east of here. There’s no way to fight it. And you can’t treat a tree that’s got it. So, man, it just makes you wonder: “Well, God, that’s the end of that. Or could it be?”

RUBY: It could wipe out an entire state.

RUSCHA: Yeah. It causes you to examine your own navel.

STERLING RUBY IS A LOS ANGELES-BASED ARTIST. HE WILL BE THE SUBJECT OF THE SOLO EXHIBITION “THE JUNGLE” AT SPRÜTH MAGERS BERLIN THIS MONTH.