The New “Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures” Exhibit Speaks to Us

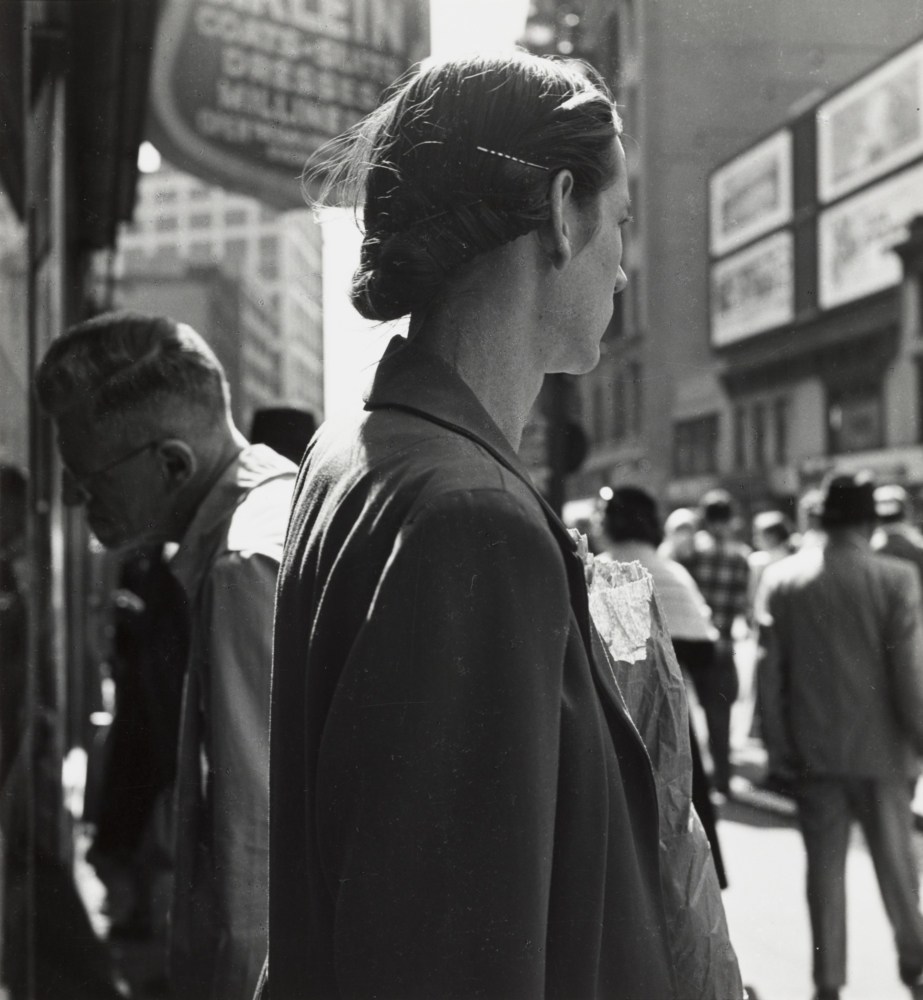

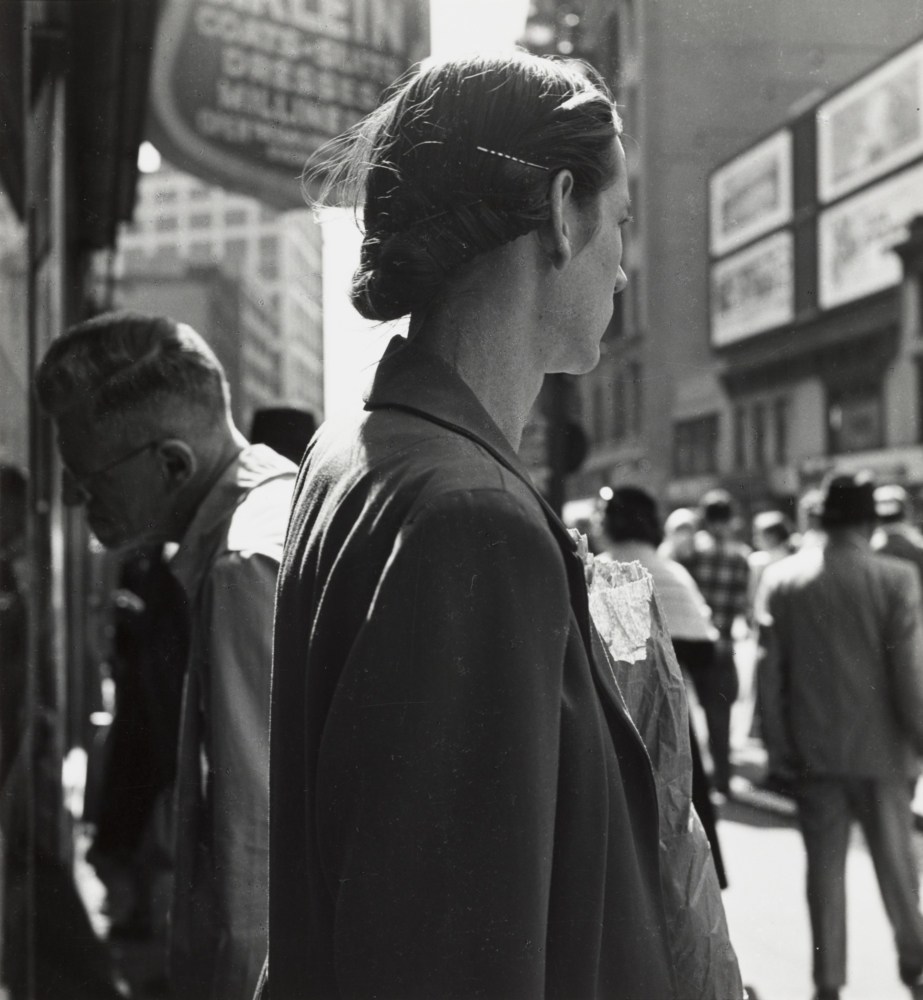

“Union Square” by Dorothea Lange.

At the front of the Dorothea Lange photography exhibit, two women are reading. Occasionally, they talk softly, but only about the books in their hands, and thus with the air of an impromptu book club meeting. Their backs are turned to the black and white prints staggered along the wall behind them.

This juxtaposition—reading in the photography exhibit—might seem odd, even downright rude, if not for the fact that it’s the point: From now until May 9th, MoMA is home to “Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures,” a retrospective project with a linguistic twist put together by curator Sarah Meister, whose book on the famous Lange image “Migrant Mother” underpins the entire show. While leading me around the busy exhibit on a blustery Thursday afternoon, Meister reveals that the relationship between the textual and the visual is not only central to this exhibition, but was, in some ways, catalytic to its conception. “As we were working on [the show], we read from Lange’s oral history, and she says that all photographs can be fortified by words,” Meister explains, “I thought, I totally disagree. But what an amazing statement from someone who dedicated their life to making images. It got us going on the question of whether it felt urgent, now, to look at Lange more deeply.”

The answer to that question, as evidenced by both the crowd that hums around us as we make our way to Lange’s most popular pieces and the influx of other Lange-centric publications out this year, was yes. If the advent of this project feels massive in scope, its execution is acute, personal—founded on the same basis as Lange’s 1939 photo book, which strove to give voice to the largely voiceless people she photographed. With the Dust Bowl’s defining image as her massive claim to fame (you would be hard-pressed to find a high school history teacher’s 1930s PowerPoint that doesn’t include “Migrant Mother”), it’s perhaps too easy to forget that while Lange’s images have always spoken to us, her subjects weren’t always able to speak for themselves. Words were perhaps important to Lange because they weren’t always implicit; rather, they were hard-earned.

When we return to the front of the exhibit, the two women are in the same place, still reading. Meister takes out her phone and snaps a covert picture, delighted by their engagement with every level of what the collection has to offer. Though Meister tells me that part of the goal of this exhibit is to tease the connection between words and pictures apart, watching her take the photo, it’s hard not to feel that they’re instead being twined tightly together. What is a photo of two women reading inside a photography exhibit, if not words and pictures? The relationship between the two modes of communication feels neither divided nor linear here, but rather concentric, layered rings of meaning and interpretation that circle right around into comprehension, clarity, and compassion. Here, Meister speaks on seven stand-outs from the exhibition. That is to say, here are some words on pictures.

———

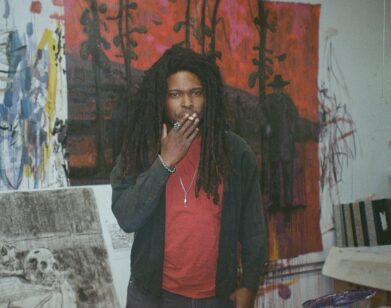

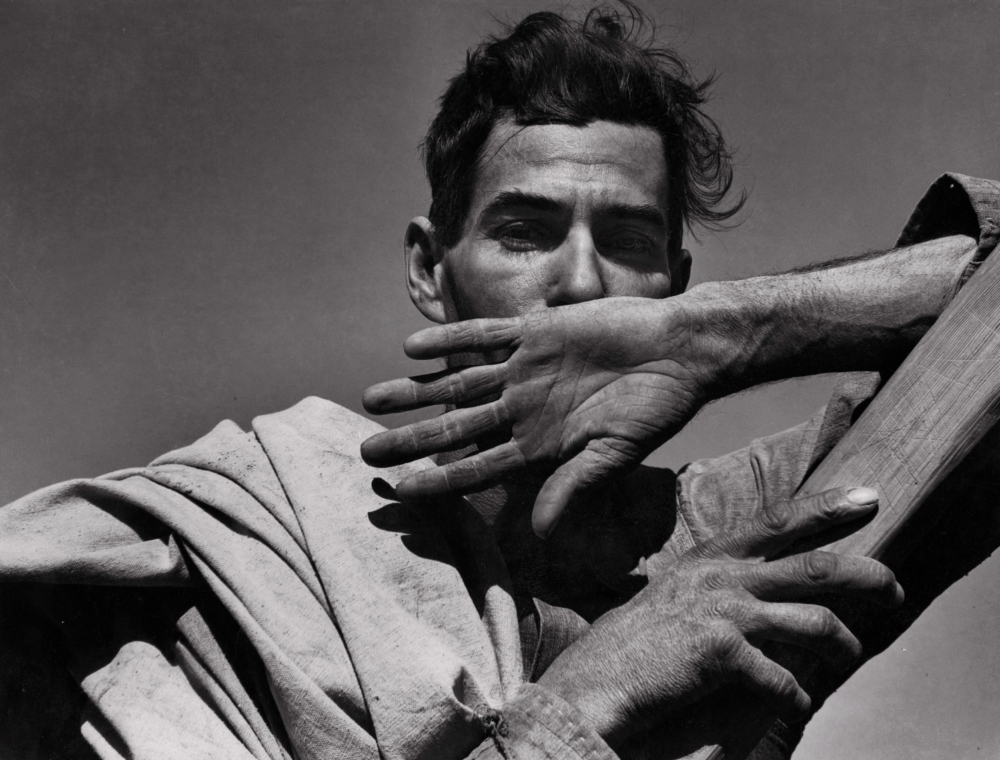

“Migratory Cotton Picker,” Arizona, 1940

“Almost from the very start, we knew this was going to be the picture that you see walking into the collection. For me, the idea of this gesture, which—it’s been said he put his hand up to hide the fact that he was missing teeth, which may or may not be true—certainly in a show about words and pictures, this idea of blocking your mouth is significant. And, of course, it’s such a striking picture, and you can almost read his hand as the arid landscape that is the nexus of the whole photograph. It was important for us—because the show is called words and pictures—to have it juxtaposed against a wallpaper that was made up of the endpapers from Lange’s 1939 photobook An American Exodus, which designed and printed the voices of people in pictures such as this one.”

———

“White Angel Breadline,” California, 1933

“If Lange’s most famous picture is ‘Migrant Mother,’ certainly ‘White Angel Breadline’ is her second most famous. At the time of this photograph, she had been operating a very successful commercial photo studio in San Francisco and all of her clients were among the elite. She describes this story: ‘I was just gathering my forces and that took a little bit because I wasn’t accustomed to jostling about in groups of tormented, depressed, and angry men with a camera.’ And you can almost see the way in which, even though she evinces this deep sympathy for the people in front of her camera, she’s also separating us and them from us pictorially. You have these strong diagonals. This idea of how one man turned toward her in a sea of men turned away becomes then a metaphor for how people operate in the world—certainly at that moment—and how you can be both singular and swept up in something that has nothing to do with you.”

———

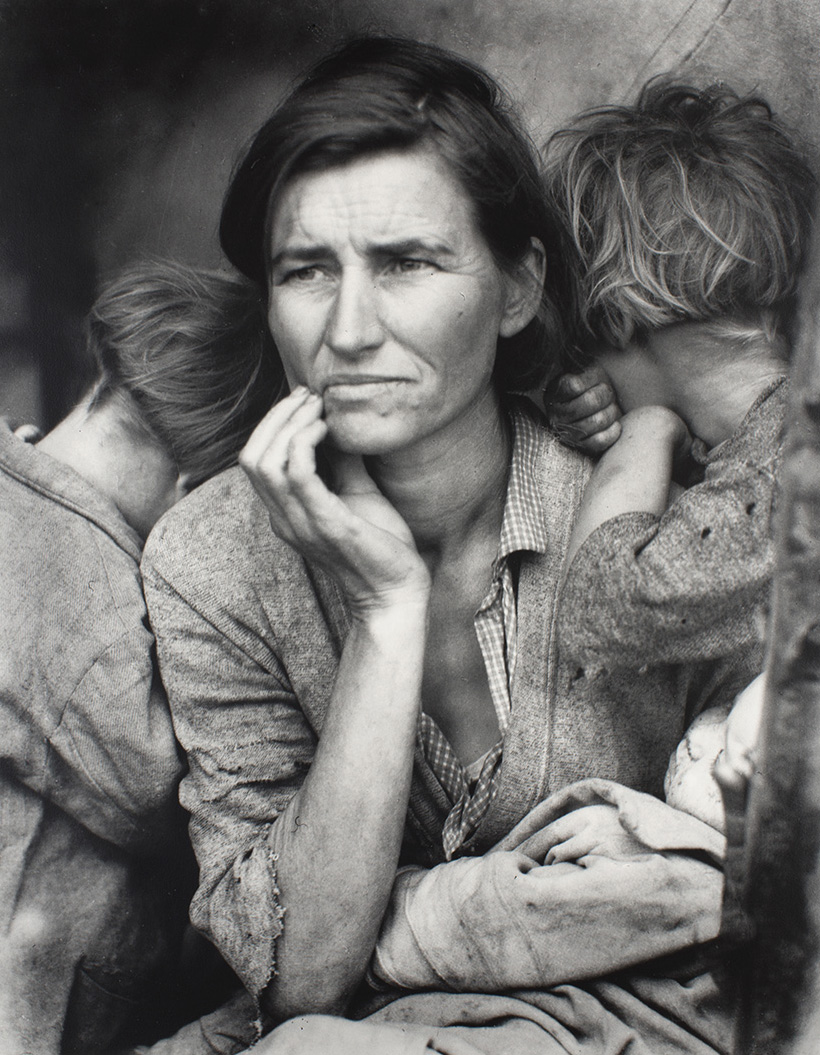

“Migrant Mother,” California, 1936

“While we were doing the research for the book, I was struck by how many different kinds of words were associated with this photograph—true words, false words, poetic words, polemical words, Lange’s own words on it in 1960. But that wasn’t until almost a quarter-century after it was taken. It wasn’t even called ‘Migrant Mother’ until 1952 and in The New York Times, when it was first published, they called it ‘Destitute Mother,’ the type aided by the WPA. A month later, The New York Times published it and airbrushed out the children and made it look like this dark tent was, in fact, a blue sky with some wispy clouds. And yet the picture was almost immune to all of this. It didn’t matter what was said about it. It holds such a unique place in the history of photography and the American imagination as this sort of emblem of the Dust Bowl.”

———

“Towards Los Angeles, Calif.,” California, 1937

“So this is one of the examples of words in pictures which, I think, is something Lange does exceedingly well. There’s this idea of, how do you embed a paradox in a single image? And here you have the man reclining on his chair saying, ‘Relax, next time try the train’ juxtaposed against these two men carrying everything that they owned on their backs. Such a train ride wouldn’t be an option for them.”

———

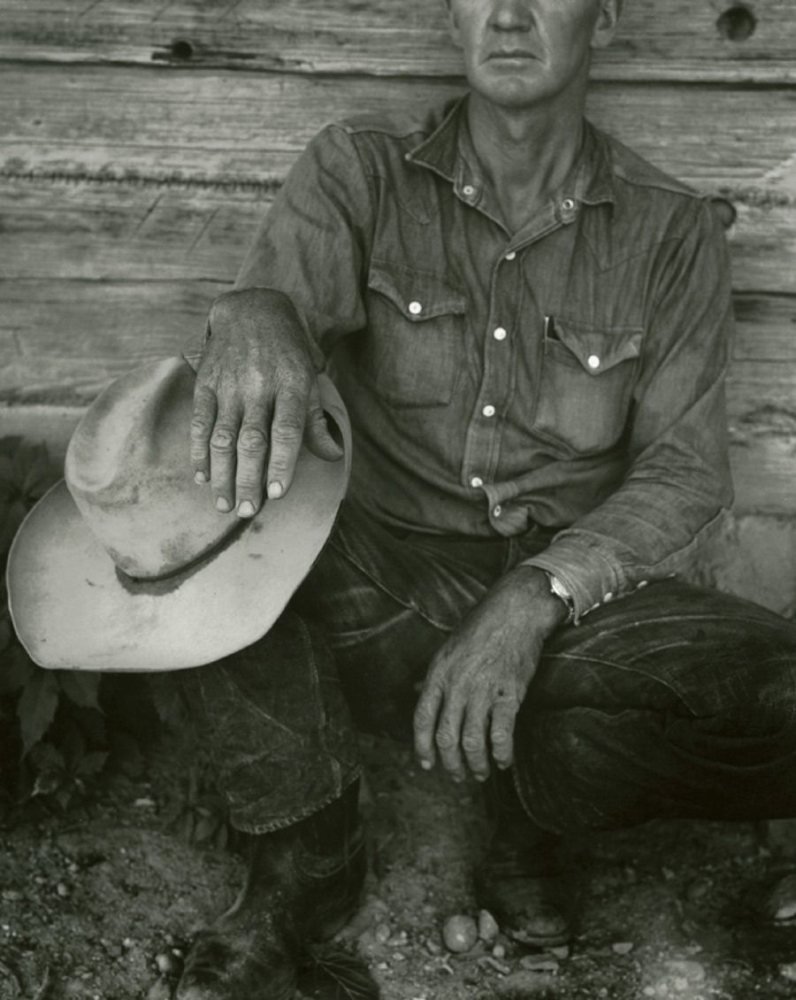

“Jake Jones’ Hands,” Utah, 1953

“Life Magazine deserves a mention here because it’s the kind ur-example of that very distinctive marriage of words and pictures throughout the 20th century that photographers both hated and actively sought. The best example of that is this picture, where the photograph that Lange made is of a man with a denim shirt and his fingernails and the buttons of the shirt all picking up on the same highlight, the same register. Life Magazine cropped it to just be the man’s hand—and you can see why that would have been ultimately so frustrating.”

———

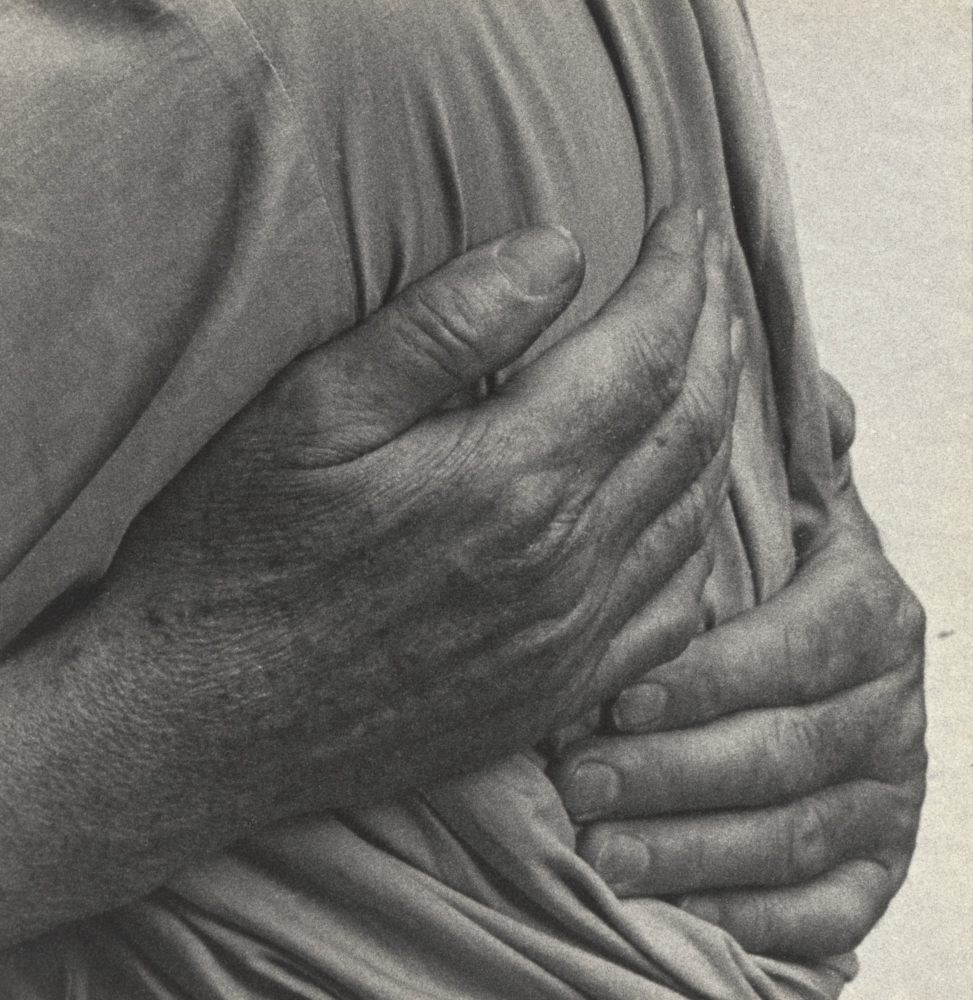

“Paul’s Hands,” 1957

“Someone asked me, ‘Did you learn anything in this show?’ Of course, the answer is: I learned a ton. Sam Contis was in our new photography show in 2018, and while she was doing that show, she heard that I was working on the ‘Migrant Mother’ book. I told her I was thinking about turning my little Dorothea Lange idea into a bigger one and that she should stay in touch. She ended up going on several road trips, thinking about Lange, diving into the archives, thinking about what was it that so attracted her to Lange’s work. She really sat for this for a long time—her practice, in general, is both observational and very archival driven. And she came across this picture—this is a photograph from the 1966 retrospective and Paul was Paul Taylor, Lange’s husband. I had never thought twice about this picture. But it was Sam who pointed out to me that this was actually a really enlarged detail of a much larger picture of Paul hugging Dorothea Lange. It’s not by Lange at all. And yet in its distillation, it became hers. It’s almost the opposite of the Life magazine picture, in which she might have objected to the cropping. Here, she cropped someone else’s work and called it her own through that act of cropping.”

———

“Union Square,” New York, 1952

“Lange made only one picture in New York that’s in this exhibition. This one was called ‘Union Square’ and I love it because how you show a picture of interiority told exclusively through surface is a really interesting conundrum. The light on the bag, the light on her hair. This was actually made for the 1966 retrospective here, but the negative was first exposed in 1952 when Lange was visiting New York and had a one-person show here at the museum. In that show—this is another origin story for this exhibition—in that show, she writes to Edward Steichen, right before she comes to New York, about another photograph. She writes, ‘This is an example of words and pictures where each enlarges and enriches the other, I think. It might be interesting, though unconventional, to show these words along with the print.’ That was five days before the show. And, of course, they did it. I love the idea that all of these very senior men, directors of the Department of Photography at MoMA, they’re all listening to her. They’re just like, ‘Okay, boss.’ I think there was such a deep sense of conviction and clarity for her about what she was doing and why she was doing it. I attribute the success of the show to that. She has such clear-eyed observation of authentic connection that, sometimes, feels woefully absent.”