Eating Paint with Djordje Ozbolt

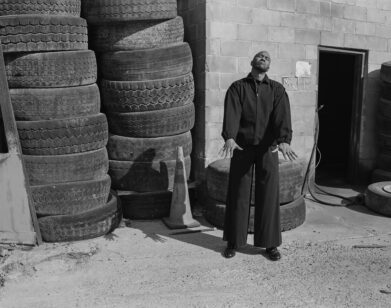

ABOVE: DJORDJE OZBOLT IN NEW YORK, JANUARY 2015. PHOTO BY FRANK SUN.

“That’s called Self-Improvement,” Yugoslavian artist Djordje Ozbolt says while looking at one of his newest drawings. The black-ink image depicts an androgynous cartoon figure holding an elongated knife in one hand and its own head in the other. Blood spurts from its neck, creating a pool on the surrounding ground. “It was inspired by the beheadings of ISIS. I had the radio on for three days, the news radio. That’s bizarre listening to the news all day,” Ozbolt continues.

Born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, but educated and based in London since the mid ’90s, Ozbolt uses humor to convey frivolous and imaginary images as well as comment on society and deal with serious subject matter, as seen in Self-Improvement. His newest works are currently on view in Ozbolt’s first New York exhibition since 2008, “More paintings about poets and food,” at Hauser & Wirth’s Upper East Side location. Taking over the entire three-floor gallery, he presents drawings, paintings, and sculptures that he says represent “the essential Ozbolt.”

On the top floor, hanging opposite of Self-Improvement, is another ink and paper drawing that shows Jesus on the cross. Rather than facing the viewer, however, Jesus faces the wall, drawing attention to the cross itself. Other scenes depict things like orgies, and nearby, a paint-splattered bust stands on a pedestal, playfully titled Let Her Eat Paint!

Central to the exhibition is 50 ways to leave your lover, a compilation on the second floor of exactly 50 canvases, each of which is drastically different from the others. From abstracted black-and-white images to clearly represented recurring themes, such as another Jesus on the cross (this time facing the viewer), a hamburger in an unprecedented setting, and origami figurines, the paintings bounce off each other, providing Ozbolt’s complete oeuvre.

Taking time away from his two 11-year-old sons and wife, Ozbolt met us in New York prior to the show’s opening and spoke about his process.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: So for this series, where was the jumping off point? Did you always see it as a whole?

DJORDJE OZBOLT: Yes, in a way. When I knew the dates for this show, I went to my studio to think about what I’m going to do. More or less, it’s a similar work to what I’ve done in the last few years. I decided to pull out some canvases, start painting, and after a few days, I thought this could be a good idea, to do almost like a diary of studio time and do a painting a day–or two or three a day. You can tell some took longer than others, but, for me, [the quick ones] are just as valid as the one that takes two weeks. So it started as that, and then I decided I would do a huge number because just a few of them wouldn’t make sense. They have to be in a big group to work.

I would do them randomly. I would flip through books or think about something, have an idea, or not have an idea, and just start painting. Then I would look back to them and I started seeing things that I could develop further, such as this [points to origami birds]–it appears in a painting downstairs. I thought about it more. Not necessarily all the work came out of these, but a lot came out of this. Then I started working on other works while I continued this series. So this is the starting point for the whole show, I would say.

MCDERMOTT: Were there more than 50 originally? Did you curate these?

OZBOLT: No, I didn’t. I had one, which my dog destroyed, and that was taken out, but I stopped at 50. After I did them I came up with the title “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover.” I remember that song from my youth. The number matched and I thought it would be appropriate, because when you see them in a group like this they work together. I don’t think they would necessarily work in a smaller group or on their own. When you put them together they’re all more or less figurative–it’s not one thing; it’s something. So I made the title “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” because it’s some kind of abstraction. There are 50 ways, 250 ways, or three ways, but the number matched the number of paintings, so I thought it would be appropriate.

MCDERMOTT: So when you came up with the title you were like, “This coincides with the number. I’m going to stop here”?

OZBOLT: Well, I had a plan to stop at 50. I thought it would be too much [to do more]. Every 10 that I would do, I would look at them, and 50 was the number where it all made sense. I thought, “This is it. This is enough.” Then I made this. [points to wooden cube in middle of room] It’s all found wood.

MCDERMOTT: To hold the paintings?

OZBOLT: Yeah. Some of it is from my studio. Some of it’s from my friend’s studio and some are from the rubbish bins, when they discard building materials. I assembled it into this trolley. It moves, it has wheels, and you can fit all 50 here. It ties in with, as I said, a diary.

MCDERMOTT: It’s like those are the pages hanging on the wall. So you see it all as one work not individually?

OZBOLT: Yes. This is all one work. It all makes sense only in a group, for me.

MCDERMOTT: Are they arranged in any specific order?

OZBOLT: No, they’re completely random. I can’t put them all in my studio, so I had them in grids and stacked. I told them to put it up as they unpacked.

MCDERMOTT: The ideas of Surrealism, imagination, and dreamscapes are very present. Do you ever base paintings off of your own dreams?

OZBOLT: No. I don’t want to sound lame, [but] it’s more subconscious than dreams. I just start making something and it develops, especially with paintings. With sculptures I have ideas, but even then I allow a lot to happen within the process of making it before I have a final product. It never comes out as I imagined. I find it boring if I have a clear idea. I like to allow for a lot of unknowns, even with materials. Some stuff I’ve never done. I studied painting, but I did little sculpture before I started making sculptures with different mediums. I have professional help, but I tend to make everything, then somebody else does the casting, and then I do the painting. I made the burger out of clay myself, but I had it cast in a different material. I wasn’t trained to do that, so it’s a new material, it presents challenges, and things happen. That’s what I like in the work; it keeps it more interesting for me in the process.

MCDERMOTT: So when you’re working on a painting and your imagination just goes on and on, how are you influenced?

OZBOLT: It’s really anything–it’s the old imagery, it’s the stuff I read. My studio has a modest, but really eclectic collection of books–from auction catalogues to books on disasters to books about dogs. I usually get them from friends or buy them from second-hand shops, cheap stuff. I go and flip through. It’s on a superficial level almost, because I look at the images and something clicks and I get ideas and develop ideas. I don’t spend too much [time] on developing ideas. That’s a starting point or there is something that triggers the brain. Then in the process it moves whichever way and you get the final thing.

MCDERMOTT: Do you ever look back at paintings and go, “Oh, that’s what I was thinking about”?

OZBOLT: I do, because I tend to intentionally never over-analyze my work.

MCDERMOTT: While you’re painting it?

OZBOLT: Ever. As soon as I finish one, I like to get on with the other. You can spend a lot of time analyzing and asking why and what and questions, which I don’t think is necessary.

MCDERMOTT: What’s one of the latest things you’ve seen or read that has influenced you?

OZBOLT: It was Chris Ofili’s show at The New Museum. I was writing some ideas yesterday. I’ve written a title. Sometimes I come up with titles and work from there; sometimes I have works first and then get the titles. It was “If I Was a Writer.” That’s what I’ve written on a piece of paper and I’ve got it in the hotel room. “If I Was a Writer”…it could be anything.

MCDERMOTT: Do you ever write?

OZBOLT: No. It’s just an idea for a work of art. I will make it. I have some ideas already of what kind of medium. First I was thinking about painting, now I think it’s going to be a sculpture or a small installation. But that’s the latest. So it can literally be anywhere–on the bus going from downtown to uptown and seeing something, or reading something. But there are good days and there are bad days. Some days I don’t get anything if I’m thinking about other things. There’s no rule for that. I could be watching a film and then get an idea. I always carry a piece of paper. I sound like a 60-year-old with learning difficulties. [laughs] It’s quite eclectic…I’ve had three or four shows in New York, but I had a gap of like five years. This time I felt like presenting something that is the essential Ozbolt.

MCDERMOTT: How would you define the essential Ozbolt?

OZBOLT: It was very honest. I just let go. I wasn’t thinking too much. I wasn’t editing. I just made work. Some shows I concentrate to a theme. The last show in Japan was of similar subject matter.

MCDERMOTT: The African-influenced works.

OZBOLT: Yes. I had never shown those in Japan, so I did a version of that. But for this one, I did drawings. I’ve showed drawings only a couple of times in Europe ever. So this was new. It’s ink on paper, and again, you know, I didn’t know what I was doing.

MCDERMOTT: But there’s clearly a woman…

OZBOLT: Of course, but I just started with ink. With this one [points to another drawing] I knew what I was doing, because in my studio I have Jesus facing the wall.

MCDERMOTT: Do you consider yourself religious?

OZBOLT: No.

MCDERMOTT: But you grew up with a lot of religious iconography?

OZBOLT: Yeah, Orthodox Christianity generally, but I’m really open. I’ve traveled a lot and I’ve seen different cultures. I lived in India and was obsessed with India for a certain period of time. I lived in the Himalayas, so there was Buddhism, local religions, Hinduism…

MCDERMOTT: Do you ever struggle with the idea of East-meets-West?

OZBOLT: No, I don’t. I find it quite interesting. Recently I’ve been thinking about where I come from–Serbia, Yugoslavia–and that’s exotic in terms of East/West, but it wasn’t as crazy as the Eastern Bloc because we were never part of the Eastern Bloc. We were closer and more open, but it’s still odd when I go back and think, “This is really exotic from the West,” and it’s in Europe. I was drawn to more exotic countries when I was younger. I find this fascinating.

MCDERMOTT: Do you think your work is perceived differently in Yugoslavia versus New York or London?

OZBOLT: I suppose so, [but] they haven’t seen my work. I’ve never exhibited there. I was too busy and, I mean, there is an art scene, but it’s a very closed kind of art scene. It’s a local thing. They don’t like the outsiders, and I think they would consider me an outsider because I left early and studied in England and was part of that scene in London where I went to university, did my M.A. My London gallery is my friends from university who opened the gallery. I think even mentally I tend to be closer to them. Not in terms of work, necessarily, but socially, which comes into work a little bit. But I still have that heritage that’s different. I’m sure that pops out.

MCDERMOTT: How do you think that pops out?

OZBOLT: I don’t know. You grow up in a certain place and that certainly stays with you even if you are not aware of it. I’ve never tried to figure out what element that is, but I’m sure it’s present [in the work] even if it’s just a way of thinking and seeing things. Even with a Western education, that stays with you. You see through those eyes.

MCDERMOTT: Going back to when you were younger, when did you first become interested in art?

OZBOLT: Very early on. There were so many books in the house, a few books on artists, actually. When I was little there was stuff to see in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade and there was some kind of scene of slightly older people that I followed. I really liked it, but I started studying architecture out of laziness, I suppose. My parents are architects, my brother is an architect, but I realized I didn’t like it.

I went to London in ’91 to visit my brother, the war started, and I stayed in England. I couldn’t go back because there was a draft for the army. I realized once in London that I wanted to study art, not architecture, so I never graduated architecture and I went into the art school. That’s when I started seriously working. Before then I was drawing all the time–I’ve got loads of old stuff, even back at my parent’s place, old stuff from London–I was getting more and more into that scene. It felt natural and then one day it was like, “Yes, that’s what I should do.” Now, I can’t imagine doing something else.

MCDERMOTT: What’s one of the biggest struggles that you’ve faced as an artist?

OZBOLT: It’s not easy being an artist, but it’s also easy at the same time I suppose. It’s a solitary thing, for me, a struggle in decision-making. As an artist you have a blank canvas or you have whatever is around and then that first step–what do you do? How do you choose the path? How do you start? School helps in a way, but in art school you do all sorts of things and don’t have a clear idea. I started late [because of architecture school], so I was a mature student opposed to other people. I made myself focus and start working, but it was changing from not doing much, in terms of being very free and traveling, to focusing on art. That triggered everything and I think I am still aware of the fact that whenever I have a small crisis of any kind–be it a person or dilemma in the studio or coming to a place where I’m not sure about things–I just work, and through work solve all the other issues.

MCDERMOTT: Have you always worked with this sense of humor and sarcasm?

OZBOLT: I think so. That’s one of the things I can’t escape. That’s the way I think.

MCDERMOTT: Are you a sarcastic person?

OZBOLT: I am, but not in a bad way. There is humor because we live in a world where there’s so many surreal, ridiculous, superficial things going on. I had to be sarcastic. That’s the way I am. That pops out in the work, but it’s just part of the work. It’s a comment on things.

MCDERMOTT: It can be difficult to convey humor through art. Do you ever struggle with that? Is it misconstrued?

OZBOLT: There is always a danger of people seeing it and just dismissing it because like, “Oh, it’s a joke.” But I think humor and cynicism come out of the work. It can deal with serious subject matter or religious stuff, like the temptations of St. Anthony. [walks to painting] These are modernized temptations, imaging what it would be now: if they were present, what would happen? That’s the humors. This is called Upper East Side. It’s how us mortals imagine the life of an Upper East Sider. [laughs] It’s my interpretation.

MCDERMOTT: So how do you know when it’s finished?

OZBOLT: I work until it’s finished. [laughs] No, I suppose visually. As an artist, I think you just know. If you work for a certain number of years, you know when the work is finished. There’s always more that you can do. When I see some of my [older] works, I immediately see things I didn’t see before. If you have a distance, you see things you could’ve done, but I run along and discard those thoughts. It could be finished at any point. You decide as a maker.

“MORE PAINTINGS ABOUT POETS AND FOOD” IS ON VIEW AT HAUSER & WIRTH ON 69TH STREET THROUGH FEBRUARY 21.