OPENING

“The Camera Is the Fetish”: Devan Díaz on Curating Bad Girls at OCD Chinatown

Devan Díaz is living by a new principle: “Fuck reputation, be bad.” At the curator’s new show Bad Girls, now on view at OCDChinatown, emerging photographers Sebastian Acero, Fern Cerezo, Jan Anthonio Diaz, Chuy Medina, and Cruz Valdez explore sex work, motherhood, and the trans nude through black-and-white portraiture along the gallery’s pink walls, with an archival photo from Reynaldo Rivera and a giant high heel sculpture by Jessica Mitrani. At the opening last week, every misbehaved diva in New York came through in a moment of communion that brought our fashion director Dara to tears. To process it all, she called Díaz to talk about fetishes, ex-boyfriends, and the act of interrogating femininity behind the lens.—MEKALA RAJAGOPAL

———

DARA: I want to start with the action. How was the opening? Did you see anything crazy? I was there.

DEVAN DIAZ: A lot of divas were there. I had to take a bathroom break with my friend and she told me she was high as hell off a Percocet, but I actually needed the break because it gets really, really hot in the gallery.

DARA: It was like 100 degrees in there.

DIAZ: All the Bad Girls body heat. But the name of the show really started to take on a personality because there were many little tiffs and fights between me and the artists in the show.

DARA: During the opening or before?

DIAZ: Right before the opening. I unfollowed a friend.

DARA: Are you serious?

DIAZ: I was a bad girl. I feel like everyone was giving that bad behavior. Alternate title: Misbehaved Girls.

DARA: [Laughs]

DIAZ: What did you see at the opening?

DARA: It was literally every fierce queen in New York I’ve ever seen all crammed into one room. Everyone’s ex-boyfriend was there also. It was really ex city in there.

DIAZ: [Laughs] Fern invited so many ex-trades.

DARA: That’s what I mean. And it’s very vulnerable to put your art on a wall and then have all the just former flames of your life come look at it.

DIAZ: “I did something with my life.”

DARA: It’s pretty fab. I had a very visceral reaction to the show at the after-party.

DIAZ: You were crying.

DARA: I started sobbing and I didn’t even realize the effect it all had on me until I was talking to Sebastian [Acero], who has two pieces in the show, a photo of Karmi and a collage of Polaroids of Cruz [Valdez] post-surgery. Sebastian was just talking to me about what the photo of Karmi meant to them, and it was this kind of voyeuristic experience that I feel like a lot of queer children have. They were saying that their mom was a hairdresser, and it’s that experience of watching a beautiful woman get her hair done and longing for inclusion in that experience, but always feeling a sort of arms-length distance to it. Never being in the chair or being the hairdresser—

DIAZ: Or the girl in the picture.

DARA: Yeah. You’re just watching. And that gave perspective to a lot of the other images. It just hit me, and I was saying to you at the after-party, “Thank you for putting this experience on a wall for people to go look at.” Because I feel like there’s a lot of these fab portrayals of femininity that are really the moment right now. It’s very trendy to have an interrogation of femininity, whether it’s The Substance or the Barbie movie or even the fucking Taylor Swift or Beyoncé shows or whatever. But I always feel like the experience of longing towards femininity is not always shown. It’s a little bit like, “Oh, it’s so hard being a girl.” And it leaves it there.

DIAZ: Yeah.

DARA: But it’s also hard to be wanting that. That really shows up in a lot of the images and I was really struck by that. Was that an intentional thing that you were looking for? What was the impetus for you to put all these things together?

DIAZ: I think the way that it began was our friend Fern [Cerezo], who was an artist in the show and has the largest images in the show. Her reaction to cameras sort of was the thesis for the show.

DARA: What is Fern’s reaction to cameras?

DIAZ: She won’t allow other people to photograph her. Anytime you try to take a photo of Fern, she does not allow you to witness her through your camera.

DARA: Yeah. It’s like the hand covers the face or there’s a veil or it’s a turn away.

DIAZ: It’s always that. There’s something I like about that sort of modesty, but it made me think of the way that girls and women use cameras. It’s Omegle tea.

DARA: [Laughs] Yes.

DIAZ: If you can position the camera in a way that captures you, in a way that is perhaps not at all a full view of yourself, but if you can see a glimmer of that girl in a phone—

DARA: In a controlled frame.

DIAZ: Exactly. She is capable of becoming real.

DARA: Yes. Wow.

DIAZ: Then the camera became the opposite of Robert Mapplethorpe’s idea of fetish. So, instead of the thing in front of the camera being the fetish, the camera itself is the fetish. I sort of thought of the camera as a fetish tool, like a whip or a chain, something that can constrict. And how women and feminine people use the constriction of femininity to their advantage.

DARA: The way a high heel makes your leg longer or a corset makes your waist smaller. It’s using a certain type of constraint.

DIAZ: Exactly.

DARA: Work.

DIAZ: And no piece in the show exemplifies that more than Jessica Mitrani’s single shoe, that massive Vivienne Westwood platform that was made for two feet.

DARA: Oh my god, that shoe is so major. It’s in the middle of the gallery and it’s on a block and it’s just a two-foot-tall shoe.

DIAZ: It’s 25 inches, yeah.

DARA: A 25-inch-tall black patent leather heel with an ankle strap.

DIAZ: And I hadn’t thought of it this way, but once we put it in the middle of the gallery, it felt like a stand-in for the camera. It’s pointing at everybody because all of the images in the show revolve around it. So it’s about how feminine people can use the bondage of femininity to their advantage and outsmart it, but also inevitably still end up trapped by it.

DARA: Yeah. Wow. And then the shoe is in that picture of Crystal Renn. Who took that picture?

DIAZ: Jessica made the shoe and the photographer, Ruven Afanador, made the picture of Crystal Renn wearing the shoe, which is so major to me to have people like Ruven or Reynaldo [Rivera], who are [part of] this canon of Latin American photography. Even though the show’s not really about that. I mean, the show’s definitely about Latina mode being on, but it’s not about that. [Laughs] But that was gifted to Jessica from Ruven and we just put it up for reference, because otherwise, people think it’s like an elephant shoe.

DARA: Right, right.

DIAZ: I really wanted to try to create a sort of femininity that dolls and gays traffic in, but it’s not exclusive to them, so having Karmi and Crystal Renn, who are plus-size icons in my mind, bodies that are rebellious in some way—

DARA: But are also undeniably women to the rest of the world in a way that maybe some of the other bodies in the show are questioned. And there’s something in the connection between the two of them that really does something, I think.

DIAZ: Yeah. I went to L.A. to hand-deliver the Reynaldo print and while I was there. I said either to Reynaldo or someone else, “Mentally ill and plus-size women are part of the LGBT community.”

DARA: [Laughs]

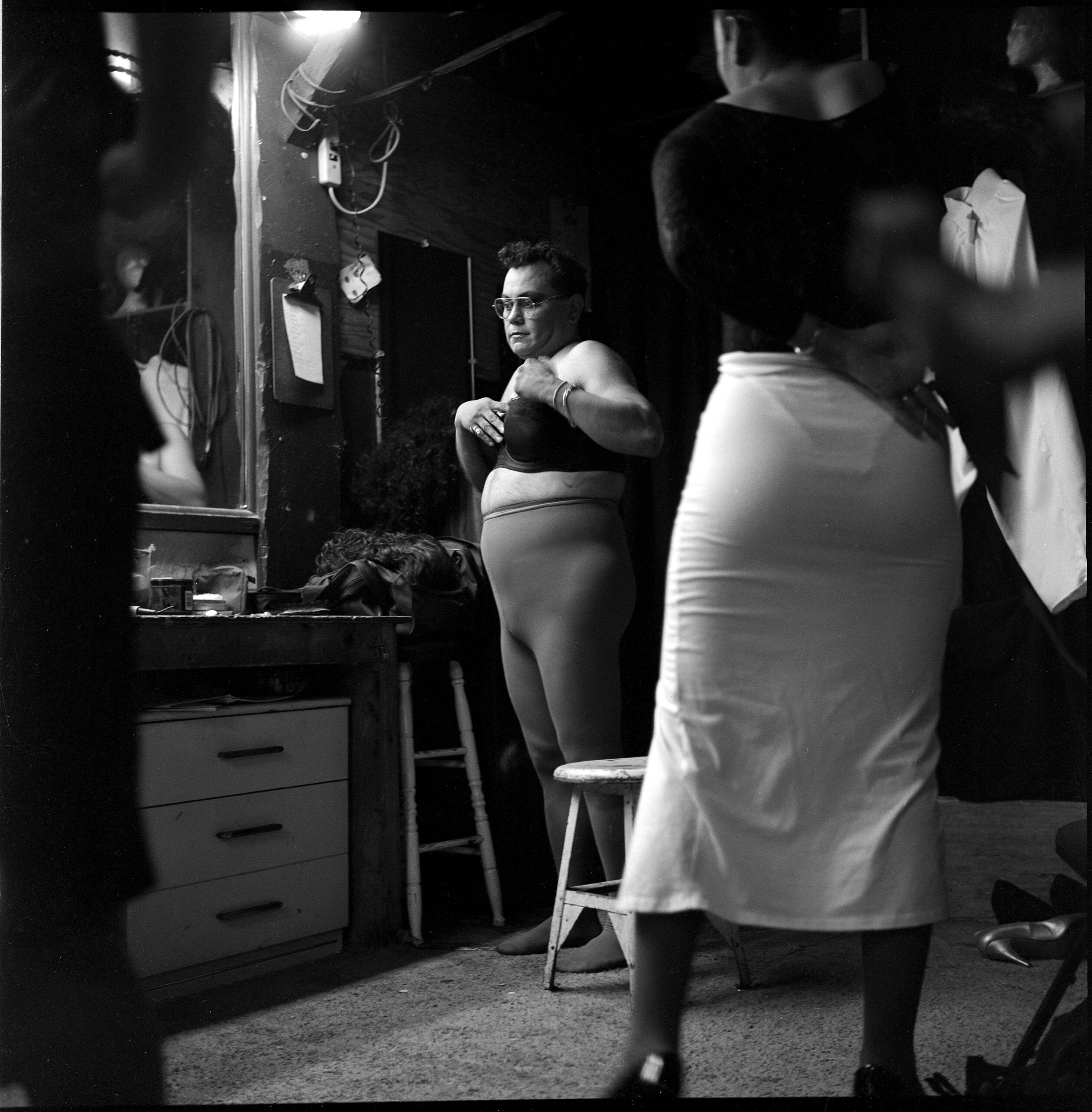

DIAZ: Which not to say that Karmi and Crystal Renn are mentally ill, but they’re bodies that are outside of something. So it really meant a lot to me to include the Reynaldo photo next to Karmi because the photo Sebastian took of Karmi, she’s so perfect. And the photo by Reynaldo is of this performer who’s not ready to be looked at, and in this quiet pensive moment. Reynaldo told me that he hasn’t shown this picture because a lot of people say it’s exploitative. I don’t understand what’s exploitative. Maybe her unawareness of the photo being taken. Is it because she’s not a thin person? I don’t necessarily see what that is.

DARA: Wait, can you describe the picture?

DIAZ: Reynaldo’s photo is of this performer, Olga, from this club in L.A. called the Plaza in 1993. She is just wearing tights and a bra, and she’s backstage in the midst of getting ready, but she’s not quite ready. And she’s sort of dissociated, maybe having a private thought moment. Olga is not alive and actually never got to see any of the images that Reynaldo took of her. So this image really has never been seen before. I think anyone who prepares themselves, who cinches and tucks and pulls and yanks and gets ready to be seen, can understand this photo intuitively even if you can’t know concretely what she’s thinking. And then it really felt important to include some of the images that are so constructed, like Cruz’s image, to sort of show what that construction—

DARA: Looks like on the other side.

DIAZ: Yeah.

DARA: But it’s funny because the way Cruz makes pictures is so constructed, but that photo has so much drag in it. It’s backstage, there’s hair, there’s makeup, there’s glamour. Cruz’s is so naked and bare and raw, but then the lens through which that bareness is visualized is so the camera is in drag. It’s so chosen and considered and aggressive and confrontational. So even if she’s not a performer, something’s being performed.

DIAZ: Yeah.

DARA: And then you saying the thing about “yanked,” even though Crystal Renn is one of our most beautiful examples of cis womanhood, she is so secretly famous for wearing face tape all the time.

DIAZ: I didn’t know that about Crystal. Beautiful. Now everyone wears face tapes.

DARA: Yeah. But it’s classic Old Hollywood. They’ve been doing it since the ’30s, but now it’s public knowledge. I just think it’s so fab that she allegedly would always bring it with her to set, and it’s such a good connection with the Reynaldo picture. It’s like the face tape is something no one’s meant to see and retouching is something no one’s meant to know. And even the way lighting is used, she really uses it to carve.

DIAZ: But also to hide, because I don’t think she would mind me saying this, but her newborn vagina is on full display being penetrated by this abstracted object, but she’s using light to also hide it so we can’t get all up in it, which feels like a balance that women have to do. I mean, even Crystal Renn, her memoir is called Hungry: A Young Model’s Story of Appetite Ambition and the Ultimate Embrace of Curves.

DARA: Oh my god.

DIAZ: There’s also something in the show about ambition, because it is based on a novel called Bad Girls by Camila Sosa Villada, who’s this Argentinian writer. The show wasn’t initially going to be based on this novel, but I passed it around amongst some of the girls in the show, mostly Fern, Chuy and Cruz. And there was something instantly recognizable about it, but also not at all because I’m American and I don’t know the experience of living in South America and having to do survival sex work. But I live in Queens where you can see the girls on Roosevelt Avenue working, and one of those girls is my aunt. It always felt like a life that I was not too far away from, or a couple of things could happen in my life and I could be one of those girls. We took all summer to plan this show and there would be instances where one of us wouldn’t have money, so the other would buy them dinner or lunch. So I remember I decided to call the show Bad Girls because I was talking to one of the artists on the phone about how hard everything is financially for most people, and the person was like, “I don’t want to have to do sex work.” And this book that we all loved and related to just felt right, mostly because we were all misbehaved, but also because we all felt like we knew the world of the book, but also didn’t know it at all. I think that’s all of our relationship to most of the things we try to do. Something about it feels intuitive, but also something about it feels completely foreign. And the show was trying to make a bridge between those.

DARA: There’s also Jan Carlos’s picture of the mother and the child and then Chuy’s photos in the sun in this kind of relaxed state. There’s this sort of relationship between the natural and the artificial, the performed and the relaxed, and the distance and discomfort and embracing of the two things in one body. Both those opposite poles are so integral to the show in a way that I don’t always see in representations of feminine experience. I feel like one is often pathologized in favor of the other. It’s like if a woman or a person or a being is glamorous, then it’s bad. It’s a violation to see them naked or without the lights and the wig and the makeup.

DIAZ: Yup.

DARA: And then on the opposite end, if they’re being real with you, they have to discard their view. It’s very like, “I cannot wear heels. I have to wear the Birkenstock,” Barbie movie thing.

DIAZ: I was actually thinking about our experience of watching the Barbie movie in making the show. I thought hating the pink was such a disgusting choice.

DARA: Yeah, there’s this revulsion of this pendulum swing against pink. It’s like the world can’t look at pink in the same way anymore.

DIAZ: Yeah. And yet the gallery is pink mostly because of the book. The house that all the girls live in and around is pink. But the show officially became about the novel because of JC’s amazing photo of the mother and son.

DARA: Okay.

DIAZ: That had to be in the middle of the gallery. Everything had to feel like it was revolving around the mother. Because in the book, Auntie Encarna, she’s sort of the matriarch of all the girls living in her house. And she finds a baby in the park where they all do sex work, and she tries her hardest to raise this baby. And then the town sort of makes it impossible for her, so her and the baby reached this tragic end. Thankfully, it’s not the case for the mother and child in JC’s photograph.

DARA: He was telling me about them and then they came and it was so beautiful to see the kids see their picture on the wall. It was really cute. Who are they?

DIAZ: Well, her partner is also trans, so this baby is her biological child. But where she was living, everyone would sort of be like, “What is this trans woman doing with this baby?” And then she moved to JC’s family’s neighborhood uptown in a community where people aren’t questioning in the same way. So, it’s not the same tragic end that we see in the novel. I guess I wanted to use the classic tropes of art history, like the image of a new woman, images of mother and child. The trans nude, which feels so tied to pornography. A lot of trans girls that I know never knew about their existence until they saw it in pornography. And I mean, I have children in my family that I’m not allowed to be around because I’m trans and because I come from a very conservative Christian background. And I wanted to see if the presence of a child amongst all of these naked and half-dressed transsexuals could somehow neutralize the nudity and sort of take it back to nature, despite the artificiality of my newly surgically enhanced breasts out freely on the beach captured by Chuy. [Laughs]

DARA: Well, yeah. Chuy’s images feel beautifully sprawled in nature. It’s sort of closer to a Renaissance or a Baroque image. And I love that idea of interrogating these art history tropes, especially when it’s mixed with the Hollywood and fashion tropes on the other side of the show. It makes you think about how those images are even made and why.

DIAZ: Totally. And Chuy’s image of Stevie is sort of the opposite of Reynaldo’s image of Olga because her head is completely turned away. No one knows that’s Stevie other than the people who know Stevie. Stevie is the smartest, coolest girl in New York, but she doesn’t use social media and only we know her. She’s too smart for her own good.

DARA: She’s a bad girl, for sure.

DIAZ: She’s really bad. She’s the baddest girl. And her image was the hardest to hang up for the installer for some reason. Because in Chuy’s triptych, it’s Stevie, Martine, me, and a little sliver of you, but no one knows it.

DARA: Yeah, no one knows it’s my tit underneath Martine’s face.

DIAZ: And the images of you and Martine and me went up seamlessly, but the image of Stevie just would not stay, which is so true to her personality, to be difficult in the best way. She’s wearing a tiny little bikini bottom and she’s topless, but she’s not going to let you see her face. I love that level of privacy inside of that photo that is so exposed.

DARA: I love this show. I love the Cruz wall.

DIAZ: That’s another level of privacy because in Cruz’s self-portrait, you don’t see her face. If you know Cruz, obviously, she’s prolific, she’s out there, she’s working. But the collage is so tender and so beautiful and so not Cruz’s image.

DARA: Yeah. It was surprising to look at as someone who’s known her for over 10 years and literally moved to New York with her. It’s like looking at her in a way that she doesn’t present herself ever. And I think there’s something really amazing about the way that we all present ourselves, because we operate through imagery and through reference, and it’s almost like the brainwashing works. You put something in front of everyone so much, you get everyone to agree with you about who and what you are. But then you see someone else look at you and you’re like, “Wow, I didn’t see that the same way.” It’s amazing to see this new way of looking at a subject that may have a lot of control over how we perceive them.

DIAZ: Totally. I think, myself included, everyone in the show wanted to not do that anymore. I think it was all about, fuck reputation, be bad. Fuck my past, I have no exes. That’s why all the exes are there.

DARA: Yeah, exactly. Take your ex and go see Bad Girls. Also, you had clear plastic shoes on [at the opening].

DIAZ: Lucite goes with everything. And the pedestal that Jessica’s shoe is on is a Lucite pedestal that has her name on it and the size, a size 38. So, if anyone is a size 38—

DARA: You can put both your feet in there.

DIAZ: That’d be fabulous, a performance. If only I knew a doll that was a size 38.

DARA: You know who’s a size 38? Addison Rae.

DIAZ: This is an open invitation to come perform “Aquamarine”—

DARA: Inside the two-footed shoe. She’s a bad girl and would have.

DIAZ: She’s bad. And she said, “Fuck reputation.”

DARA: Exactly.