Into: David Lynch’s Decapitated Mickey Mouse

David Lynch, “Squeaky Flies in the Mud,” 2019. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York.

“Into” is a series dedicated to objects, artworks, garments, exhibitions, and all orders of things that we are into — and there really isn’t a lot more to it than that. Today: Conor Williams attempts to digest the seemingly inscrutable work of David Lynch, whose oft-overlooked visual art can be seen at Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York until December 21st.

David Lynch is perhaps best known as the auteur behind such haunting and cryptic films as Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and most recently, depending on how strictly you define the medium, the eighteen-hour Twin Peaks: The Return, a continuation of the iconic television series he created with Mark Frost. Less widely appreciated, however, is his equally stunning and discomforting work as a painter. Before he ever picked up a camera, Lynch took to the canvas, a practice he still continues today at his home and studio in Los Angeles, where—when not reporting the weather—the artist can be likely found burning through packs of cigarettes and getting his hands dirty, a daily routine he refers to as the art life: “You drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes, and you paint, and that’s it.” Judging by the 2017 documentary of the same name, it is evident that painting is Lynch’s true love. His visual art provokes a near-bodily response, even in himself. (He once remarked to Patti Smith that he would like to bite his paintings.)

While unfortunately an opportunity to literally sink your teeth into Lynch’s art remains out of reach, you can head to Sperone Westwater Gallery on the Bowery and take in Squeaky Flies in the Mud, an exhibition of recent and brand new works by the maestro himself. The show consists mainly of his paintings and drawings, murky, muddy visions realized from worlds both real and imagined, although alongside them lie several lamps and a prototype for a so-called “lollipop chair.” On my way to the gallery, as I reluctantly sipped an unfortunately foul cup of coffee, a cold, gentle rain pushed down onto the street. A gallery assistant stepped out to greet me through a hidden door in the face of the building, materializing in the mist. It was…well, Lynchian.

David Lynch, “Violet Lamp,” 2003. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York.

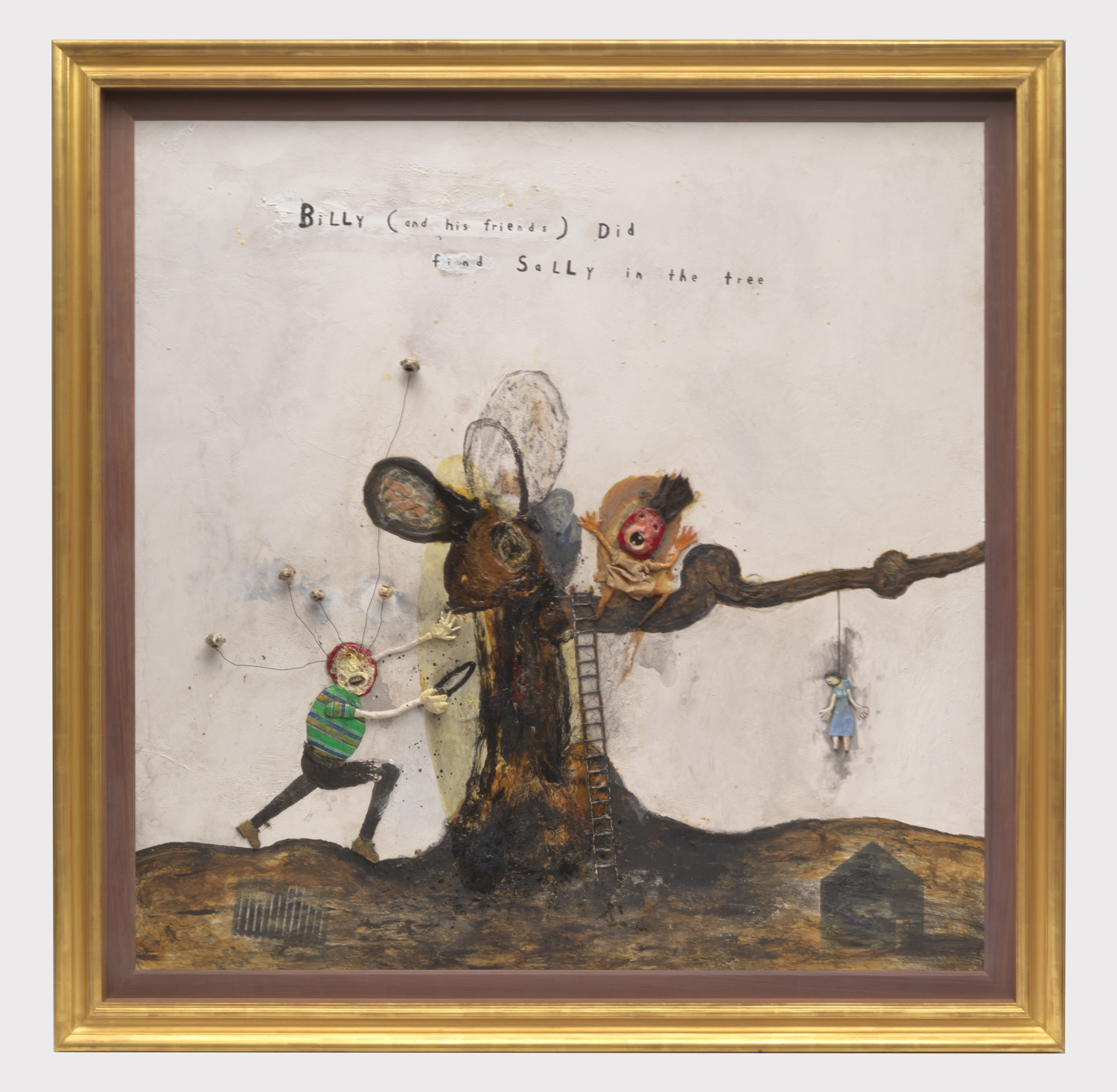

Lynch’s work has always felt distinctly hand-crafted, from the ineffable essence of the Eraserhead baby to the Kuchar-esque bird who graces the final moments of Blue Velvet with peaceful chirps. His paintings are no different; they are tactile and topographic. Gruesomely detailed with blood, shit, slugs, muck, many of Lynch’s paintings depict children as inhabitants of twisted American landscapes. In “Billy (and His Friends) Did Find Sally in the Tree,” Billy (his friends being a set of numerous miniature heads, sprouting outward from his body, comes across poor Sally’s corpse hanging from a branch.

David Lynch, “Billy (and His Friends) Did Find Sally in the Tree,” 2018, Courtesy of Sperone Westwater, New York.

Houses pop up frequently throughout the exhibition, mostly noticeably in Lynch’s drawings, a subtly recurring motif harkening back to his troubled memories of suburban living. (Curiously enough, I recently put on The Art Life, paintbrush in hand, ready for David’s words to guide my own casual process—and ended up with a canvas slathered predictably in black, the simple red outline of a house in the foreground.) The work that left its mark most viscerally on me was the violent “Billy Sings the Tune for the Death Row Shuffle,” a 2018 work in which Billy has apparently ripped the jaw from a shit-smeared dog, an act of cruelty witnessed from above by the grinning disembodied head of Mickey Mouse. The image has an eerie prescience to it, what with Disney (whose studio surprisingly had a hand in producing Lynch’s 1999 film The Straight Story) opening a streaming service that’s launched a thousand thinkpieces on cinema and artistic property. Given Lynch’s fierce opposition to any sort of interference with the creative process, and his general uneasiness with more franchise-oriented films (the time George Lucas tried to persuade him to make a Star Wars film, Lynch said the whole ordeal left him with a headache), Mickey’s wiry, decapitated form feels like the closest thing resembling a take on the matter that we might get from the infamously taciturn artist—a shocking suggestion that finds The Mouse himself complicit in depravity.

David Lynch, “Billy Sings the Tune for the Death Row Shuffle,” 2018, Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York.