Into: The Very Likable Likenesses of David Hockney: Drawing From Life

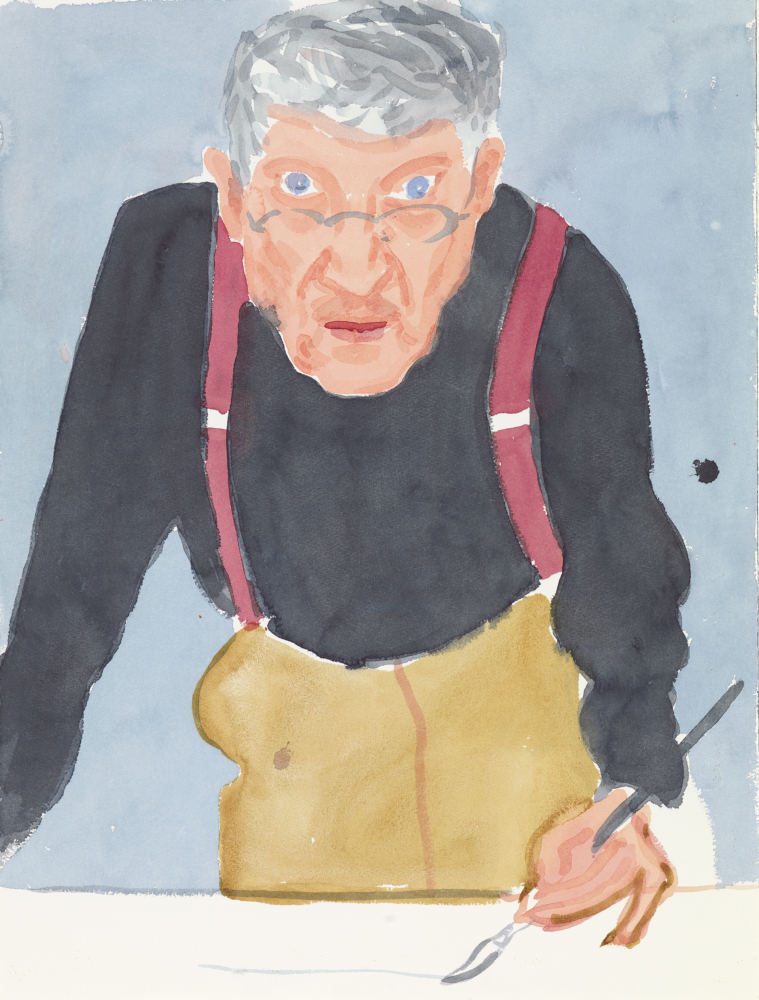

David Hockney, “Self Portrait with Red Braces,” 2003. Watercolor on paper. © David Hockney Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt, Collection: The David Hockney Foundation.

When we talk about art—especially portraiture, life-drawing—we are often hung up on the word “like.” As in: Is it a good likeness? Does it look like them? Is it life-like? David Hockney: Drawing From Life, published by the National Portrait Gallery London to accompany an exhibition that will travel to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York this October, doesn’t evade these questions so much as transcend them. Over the course of 150 pieces, Drawing From Life draws us into Hockney’s closest circle, made up of his friends Celia Birtwell, Maurice Payne, and Gregory Evans, his mother, Laura Hockney, and finally, through the book’s final stretch of self-portraits that span from the ’50s to present day, David himself.

Birtwell, Payne, and Evans were all creatives in their own right—a textile designer, a curator, a master printer, respectively. We could spend time with a little of their biographies here, but the point feels moot. After all, the book is organized into simply-titled sections: Mother, Celia, Gregory, Maurice, and David. And the pieces are as strikingly intimate as this first-name basis implies.

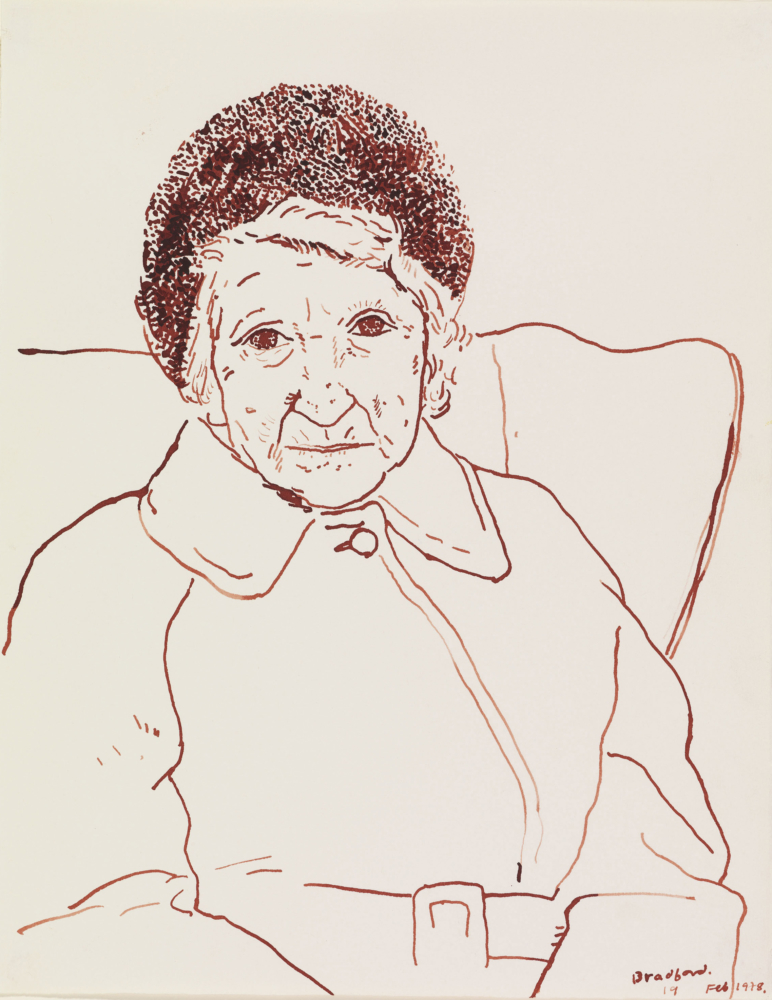

David Hockney, “Mother, Paris” 1972. Colored pencil on paper © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt, Collection: The David Hockney Foundation.

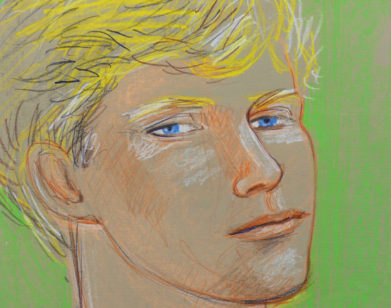

David Hockney, “Celia, Carennac,” August 1971, coloured pencil on paper. © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt, Collection: The David Hockney Foundation

Perhaps only slightly better known for his pools than his portraits, Hockney has always been understood as a draftsman with a considerable grasp of depth. Here, that depth lies not in the shadow of a diving board, but in the subtleties of his subjects expressions, the distinctive energy he lends each of his sitters—capturing something innate to their characters, something active, alive, and rendered inherent—even when his pencil captures them as they sleep.

To flip through Drawing From Life is not only to marvel at the variety of modes and mediums Hockney has clearly mastered—portraits are done in everything from pencil to paint to polaroid—in his portraits but to truly live with them. The young Celia in the brightly patterned dress becomes a Celia etched in dark jacket and pearls, edges sanded down by age, friendship, charcoal. The title of the latter: Soft Celia. A similar transformation can be seen in Hockney’s mother, a light-haired woman in a black dress done up in pastel pencil in 1973 becomes a black-hatted figure, ink demarking the ghosts of smiles past on her cheeks. And then there is Hockney himself: the self-portrait of a bespectacled young boy becoming a red-suspendered older man. This is how Hockney’s work manages to evade those questions of likeness we are so tempted to lob at portraiture. Every image is like because every subject is loved.

David Hockney, “Mother, Bradford,” Feb 1978, 1979. Sepia ink on paper. © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt, Collection: The David Hockney Foundation