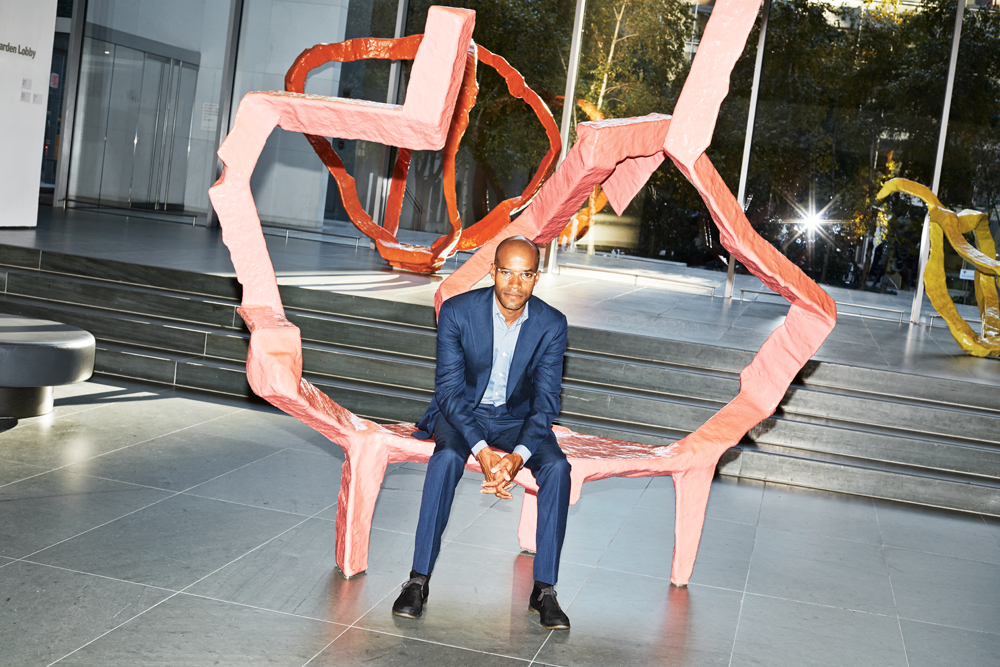

Darby English

ART HISTORIAN AND CURATOR DARBY ENGLISH AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2014. SUIT AND SHIRT: SALVATORE FERRAGAMO. SHOES: ENGLISH’S OWN. STYLING: ANDREAS KOKKINO.

In conversation, Darby English refers to himself as “not a joiner,” “not a philosopher,” “not a historian,” “a trouble maker,” “an Adornian,” “an Instagram fiend,” and in regard to his current consulting-curator position at MoMA, “an academic allowed to experiment with curating.” More than simply experimenting, English takes on all of the negotiations of his curatorial title, working with the museum on everything from acquisitions to exhibition planning. One of the smaller but fascinating perks of the position involves the occasional perusal of the little-seen masterworks in the stacks of the museum’s Queens storage facility. “It’s an academic’s dream,” he says.

The 40-year-old, Cleveland-born English also works full time as a director at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, a sort of think tank for art historians. His administrative work there, as well as at MoMA and on his own, often points in the direction of one of his overarching, long-term projects: cracking open the restrictive, tunnel-vision category of black art. For him, black is broader and more nebulous than African-American art and should allow for more complex, hybridized definitions of blackness. “A Japanese black person, a Bosnian black person, an Italo-African artist who works with sponge,” he says, “That’s what I’m talking about. As far away as possible from the parts of the black world we’ve already domesticated and covered.” English’s writings, including the book How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, have investigated the work of “nonjoining” artists such as William Pope.L and Glenn Ligon, who exemplify a porous, dualistic sense of racial identity. “What’s the most expansive experience we can have with regard to race?” he asks. “It’s one that forces us to think about race in ways we have never thought about it before.”