IN CONVERSATION

D’Angelo Lovell Williams and Alannah Farrell Are Taking Notes on Masculinity

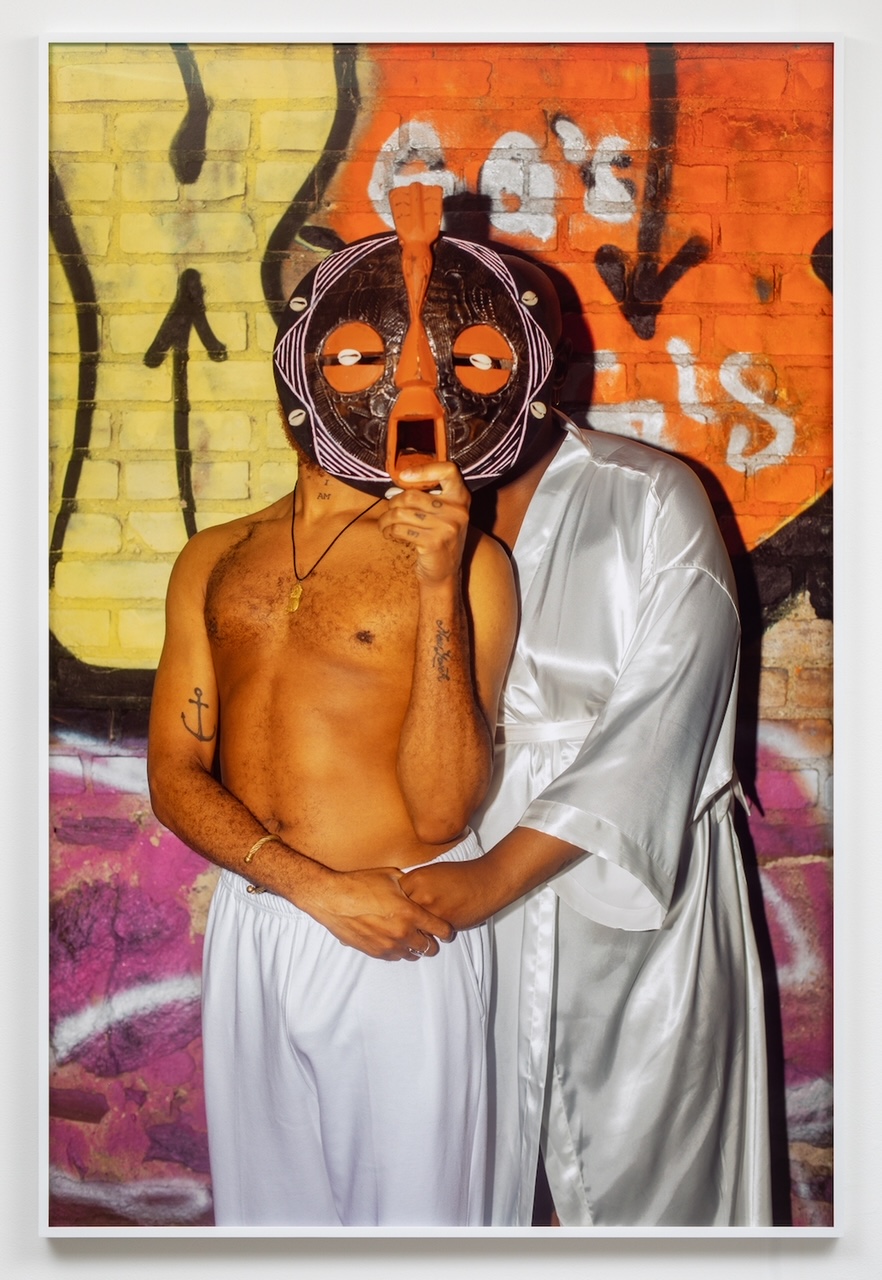

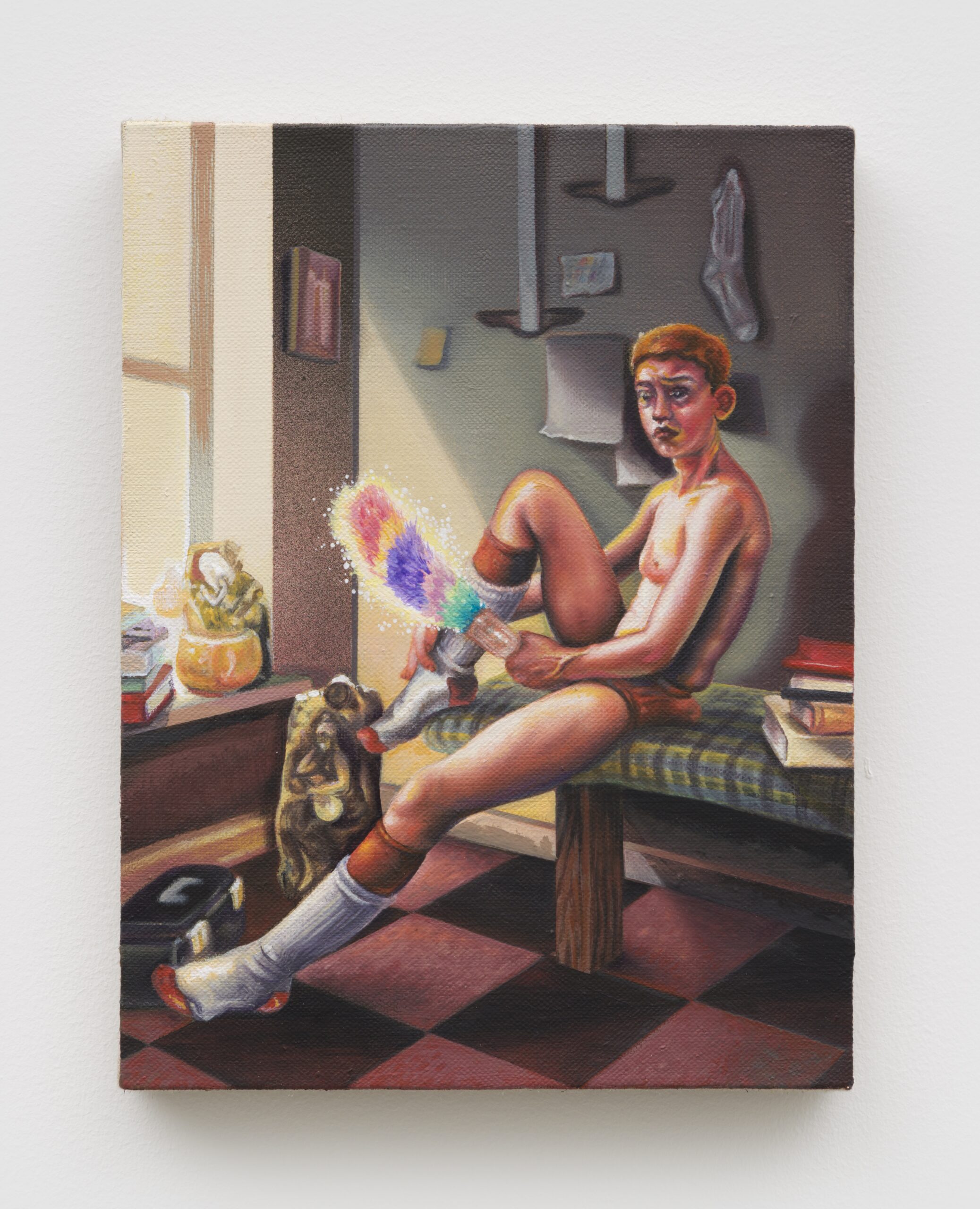

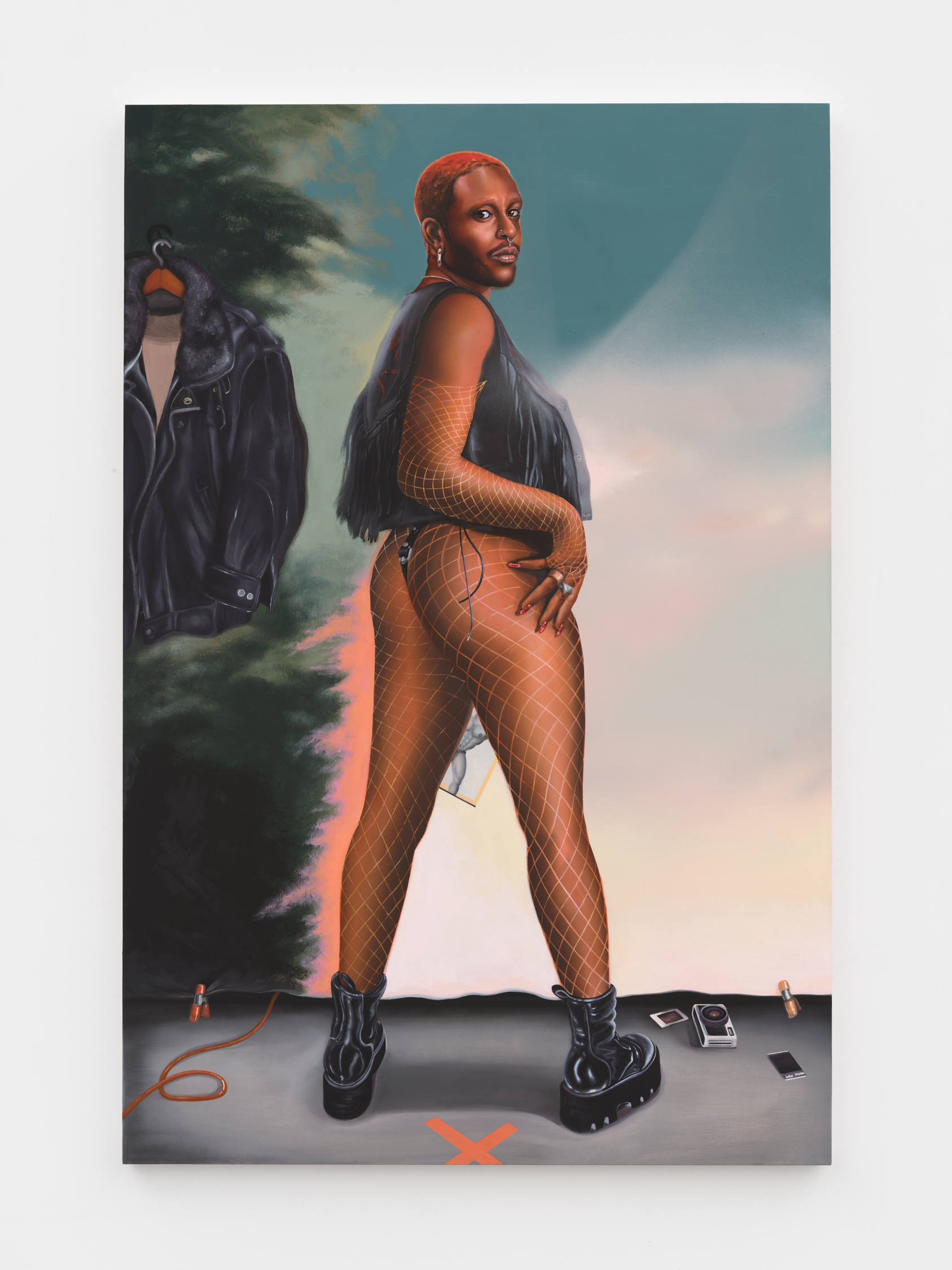

D’Angelo Lovell Williams photographed their mother’s funeral last year, and their grandmother’s two years prior. “I have these images that I literally took of my mom before she was cremated, and those are the last images that I have of her,” Lovell Williams said. “I’m supposed to be doing this because nobody else in my family is.” Lovell Williams is an HIV-positive, non-binary photographer and weaver, who’s work you’d remember if you’ve happened to encounter it, whether it’s a self portrait with a gun lolling in their mouth (Blow, 2016) or an image like The Lovers (2017), Lovell Williams’ take on René Magritte’s classic painting. “Your photographs feel very painterly to me,” said fellow New York City artist Alannah Farrell when the two artists, who are currently in an expansive, provocative group show called Notes on Masculinity at downtown gallery Lyles & King, got together over Zoom last week. At the gallery, you can find Lovell Williams’ Walk in the Spirit and Farrell’s Notes on Masculinity: A Tranny Tragicomedy, a self-portrait Farrell considers to be in conversation with their other piece in the show, a towering painting called Adonis and his Fujifilm. Below, the pair discuss chosen families, artistic genomes, and the irony of partaking in a show about masculinity given their shared affection for their mothers.

———

D’ANGELO LOVELL WILLIAMS: I didn’t see you at the opening. I got there a little late.

ALANNAH FARRELL: I might’ve bounced.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Yeah, no, it was a lot going on that day. I had just found out that my work was in the show the day before.

FARRELL: That’s so funny, I feel like that’s happened to me too. I only knew about it a little bit in advance because I was finishing a painting.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Did they see the work while you were working on it?

FARRELL: Yeah, they asked me to send in-progress shots, which always makes me hugely anxious.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Painting is always different. Painting and photography are very similar in many ways, but paintings are one of one, photographs are editions and they’re treated differently. How many of these exist? Where does it go? When I started weaving a few years ago, it was being treated like a painting or like a sculpture.

FARRELL: Because it’s a unique object? That’s funny to me, because your photographs feel very painterly.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: They are inspired by paintings. Like my image The Lovers, which is literally like René Magritte’s The Lovers, just with black people.

FARRELL: Honestly, I like yours better.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I made that image while in grad school and I was like, “I never want to look at white people’s images, paintings, to make my own work.” I had to make a lot of decisions for consistency’s sake, and even when I don’t feel like my work feels necessarily like me or looks like my work, there’s an aesthetic because I made whatever it is.

FARRELL: That’s one of the things I really love about your work. I think we were at the Clifford Prince King and Lyle Ashton Harris talk.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I was at that talk. Yeah, I just photographed Lyle yesterday.

FARRELL: That’s so fucking cool.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I met Clifford in L.A. when I was living there and we’ve just become friends. We’re both Libras. Our birthday’s are a day apart. Actually, one of the images of us, me and Clifford, is titled “A Day Apart.”

FARRELL: I love that image, where you’re kind of forming this pregnant figure?

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Yes, yes. I met Lyle Ashton Harris at Skowhegan in 2018 when he was visiting and we kept in touch. I saw him at NO BAR after Clifford and Lyle’s talk and Lyle asked me to make the photo literally the next day. I had just photographed Hank Willis Thomas on Wednesday afternoon for the New York Times Culture issue. But yeah, I’ve known about your work before I even knew that it was your work.

FARRELL: Oh, that makes me so happy. Seriously. It wasn’t like anybody told me about you. I just kept seeing it and I was like, “What is this incredible work?” I think the first time I saw your work in person was at the Independent Art Fair.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: That was my first art fair.

FARRELL: I went with another photographer friend and another trans photographer friend and we were just blown away.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Yeah. I’m glad it came together. It was almost a two-person booth, but I was like, “No, I want a solo booth.” My first art fair. I never thought that I would be in one. I’m sure you have so much persistence in painting, and I can’t imagine how long the process can be. Is anything ever really finished?

FARRELL: Oh, hell no. I’ve never finished a painting in my life, ever.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Yeah, no. I actually saw a show of unfinished works at the Met Breuer.

FARRELL: Oh, yes. That was a good show. None of my paintings ever have that. They have to be rendered and completed to a certain level for me to even not vomit. To be able to be okay with them being out in the world, but they could always be better. So they’re not finished.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: They’re great. It is always hard for me to wrap my head around how consistent many painters are. I grew up drawing. I’ve always been an image-based person, but I wanted to be an animator when I was younger. I got introduced to photography in high school and just ran with it. I pretty much stopped drawing, but it’s still a part of the weaving process for me now. But I’m not that consistent.

FARRELL: I feel like you are in your photographs.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I could be. But photography, it’s also a hit or miss for me, because every photograph is different. More recently when I was home dealing with my mom’s stuff and figuring out what I was going to bring back here, I made work. I photographed a few people other than myself, but it was mostly me just sitting in my mom’s house alone.

FARRELL: I’m sorry.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: That was just unexpected. I went home in November and I was trying to make work through that. I didn’t really have to, but when I’d go home in the past I would photograph with my mom, my grandma, my sister if it felt right. My grandma passed in 2021 and I photographed at her funeral. I photographed at my mom’s funeral.

FARRELL: How do you feel about seeing those images out in the world?

LOVELL WILLIAMS: They’re not for me once they’re released. I sit in that when I’m making the images. All of what I shot back home is film. A lot of the images I haven’t looked at yet. I looked at a few at my mom’s funeral because I didn’t get them developed until I got back here. I have these images that I literally took of my mom before she was cremated, and those are the last images that I have of her. The image of me in front of my grandma’s casket at Independent, it follows in a tradition of photographers who photographed dead people, like Deana Lawson, LaToya Ruby Frazier. It’s just that when I release images that are heartbreaking and gut-wrenching like that, I don’t think that that’s what they are. It’s like, I’ve gotten over my feelings of looking at that and then being sad when it’s on display. I’ll look at it on my own time. It’s not all autobiographical, but it’s like, I’m supposed to be doing this because nobody else in my family is. If there was someone else documenting my family, me and my family, I don’t even know if I would be doing this now.

FARRELL: Do you feel like you’re ever transmuting pain, and do you think that’s really true? Because I feel like I’ve been in New York City for a long time and I have my own chosen family.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: You have to.

FARRELL: But my biological family contains other painters, and there’s no way I could not paint.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: So what’s funny is I did 23 And Me and of course, I found out a lot. My parents haven’t done it, but I have over 1,400 people that I share a percentage of DNA with who are my cousins that I’ve never met, never seen. There’s this artist, Felandus Thames, who is from Mississippi, went to Yale, I believe. We were in a show in Memphis in 2021. I always loved his work and he popped up on my 23 And Me.

FARRELL: That is so cool.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Literally two weeks ago!

FARRELL: That gives me chills. This is probably not true, or maybe it’s true in certain circumstances, but I feel like there’s a genetic muscle memory. I went to shitty public schools. I didn’t go to school half the time. I didn’t really take the academic route to learning art, but I grew up watching my mom who did paintings for furniture. My parents were just really working hustles, but doing it through making things. I always think, well, my hand’s consistent because it’s just the fucked up way that I continually do things. But my mom has the same fucked up thing going on. It’s really strange, and I don’t know if that could come from just watching. That’s something else. I don’t know what that is, but how people have certain mannerisms that are genetically related to other people in their family.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: You watch your people, if you’re close to them, if they allow you to learn from them.

FARRELL: Yeah. But I wonder, even if you don’t grow up with someone, but you’re related, did you see any similarities with this artist?

LOVELL WILLIAMS: He looks like my dad’s side of the family. My dad has done a bunch of different things. He was a city councilman in Jackson, Mississippi when I was in first grade. Then he went to prison. Then he got out, and then he became a campaign manager for this crooked mayor. He’s been doing FEMA contracting work for a while. So he’s been in and out of the country over the years. Yeah, it’s a lot. My mom managed apartments up until her passing. My parents were inspiring for the things that they did, but I did a lot with my mom, went to a lot of antique places. All of those things that we got for my mom’s houses or apartments, they were inspiring me to make my own work. I always say that my mom was an artist in her own right, just by the things that she surrounded her space with. And my dad, not so much…

FARRELL: Well, he was prolific. I have a prolific father also.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I found out he was a Trump supporter when I went to photograph him in 2019. He had this Trump hat on one of his tables in the living room. It was in between an image of me and my sister.

FARRELL: Yikes.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: We didn’t have a conversation about it. There’s been this sort of tension between me and my dad for a while. He wanted me to play baseball. He wanted me to be an Omega like him and his brothers, all of these things that are not really me.

FARRELL: It’s kind of ironic that we’re both in this Notes on Masculinity show, and it sounds like we both really love our mothers and are kind of “eh” about our fathers.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: I think we’re bringing those aesthetics to how we make our own image and how we want to live our lives and surround ourselves with. I feel like that’s a huge part of Notes on Masculinity.

FARRELL: I agree. I very much feel that from your work. I think your relationship to masculinity is probably very complex too.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Yeah. I identify as non-binary, but that always looks like something. It is not just clothes. It’s not how I feel. It’s not how I look. It’s how I exist in the world, which is always changing. Sometimes I’m very angry, sometimes I’m frustrated and happy. It’s a bunch of different things that allow me to exist in the ways that I do to get through the days.

FARRELL: I so relate to that. I feel like people ask a lot of trans people or non-binary people both what masculinity or femininity is, and I’m just like, “I don’t fucking know, I’m learning every day.”

LOVELL WILLIAMS: How did you meet Adonis. How did that painting come about?

FARRELL: That’s a bit of an older painting. And then the other painting I have in there is a little self-portrait, which I had just finished for that show, and I actually wanted that to be in there in conversation with the portrait of Adonis. Adonis is an incredible trans man who’s very involved in a lot of different creative things in New York. I don’t actually know him super well. I hope our paths will keep crossing and that we get to know each other better, if he’s open to that. But he came to sit for me on Christmas Day about two Christmases ago. We just had a trans boy Christmas. He took some really cool Polaroids of me and we just had the best Christmas ever.

LOVELL WILLIAMS: Wow, that sounds really special.

FARRELL: Yeah, that’s how that came about. You’re going to be at Leslie-Lohman [Museum of Art] on the 15th and the 20th?

LOVELL WILLIAMS: The 15th and the 20th, yes.

FARRELL: Okay. I’ll be there. I’m going to come stalk you.