PRESENCE

Curator Legacy Russell Unpacks the Meaning Behind Black Meme

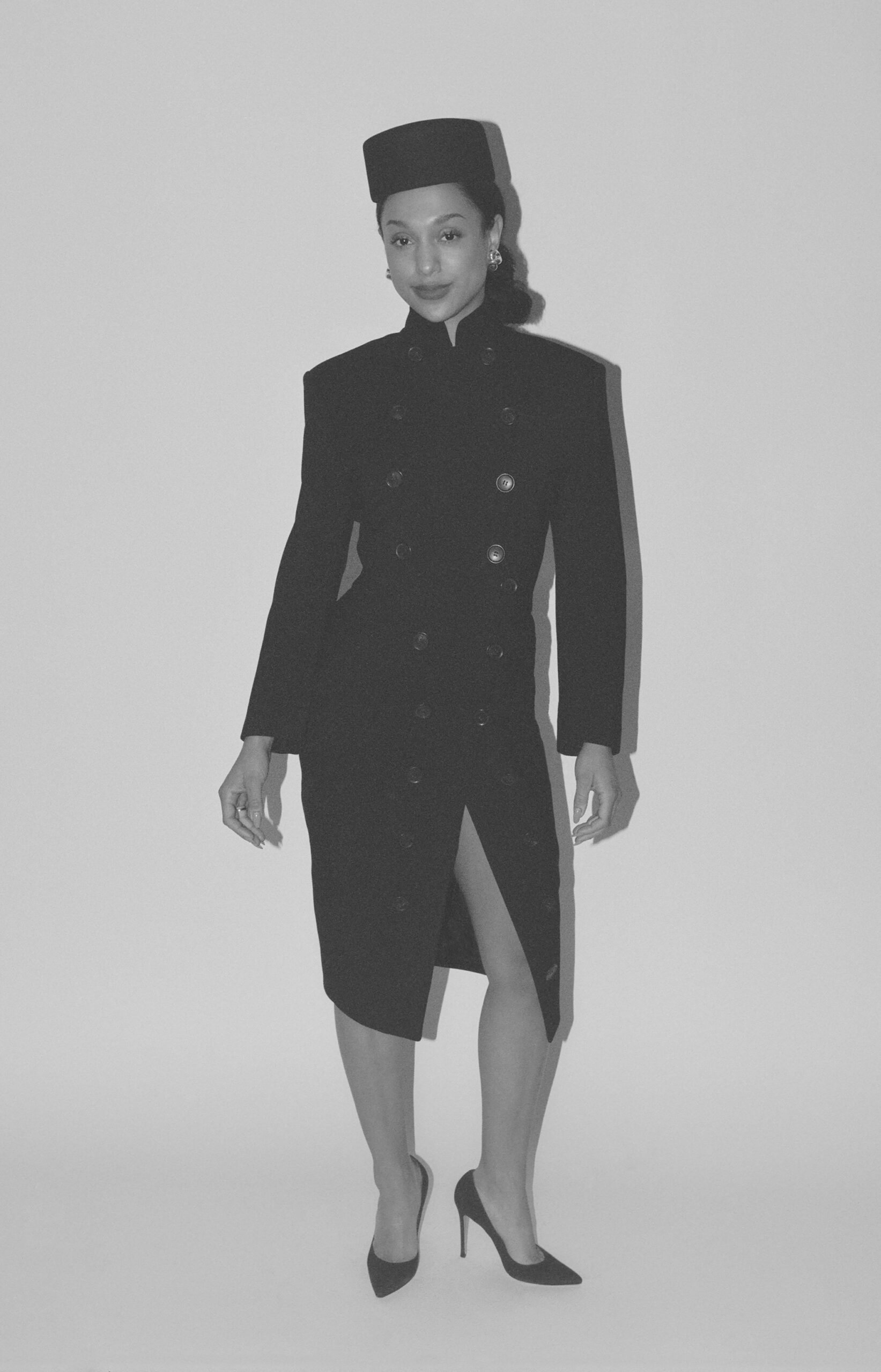

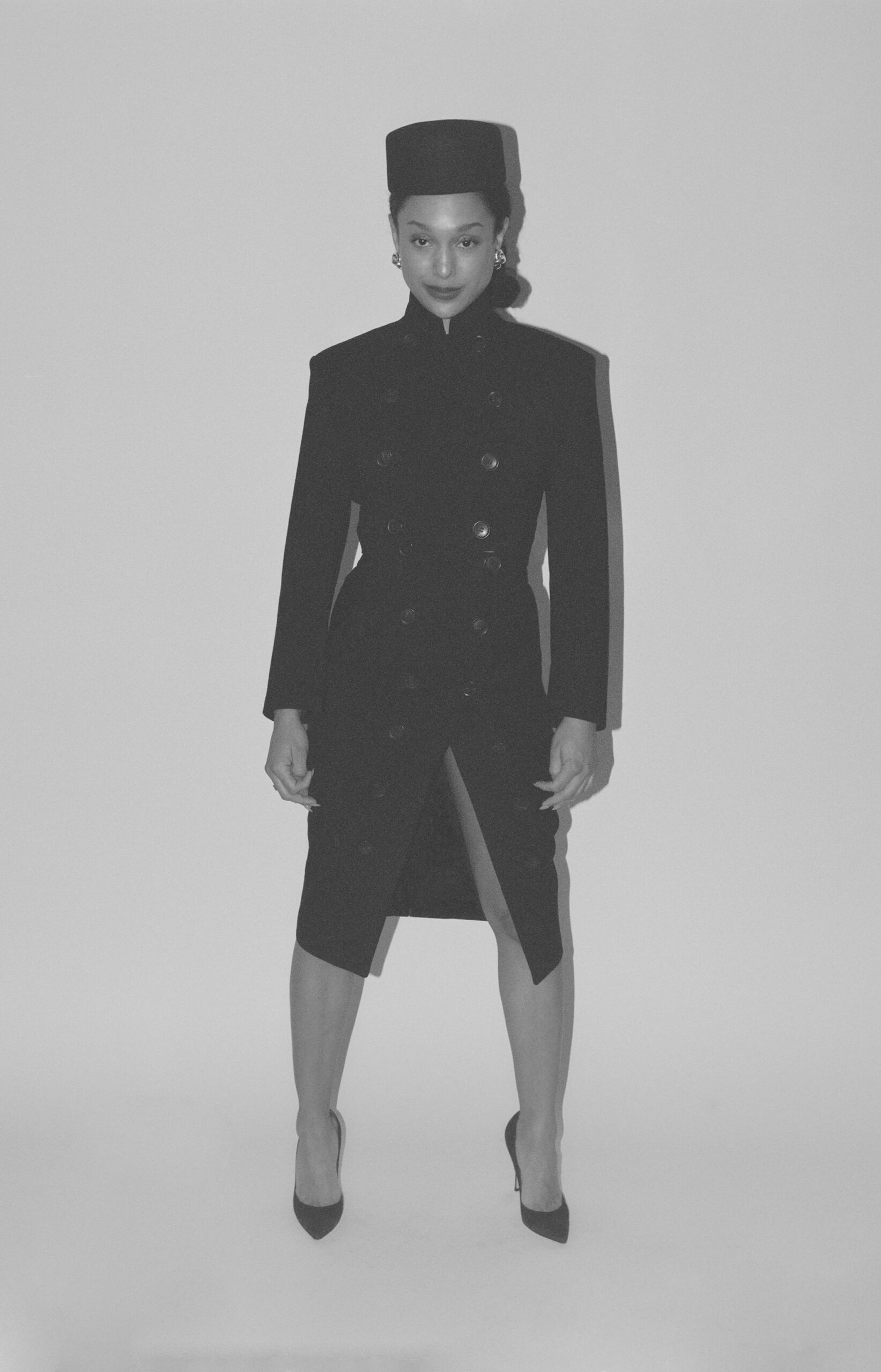

Legacy Russell wears Jacket, Skirt, and Hat Alaïa. Earrings Patricia Von Musulin. Ring Mateo. Shoes Giuseppe Zanotti.

Legacy Russell’s Black Meme: A History of the Images That Make Us is a keen study of resistance, and there’s no more exciting mind to tackle a potent array of topics: Paris Is Burning, Rodney King, Trayvon Martin, Emmett Till, Cindy Sherman, Anita Hill, Magic Johnson, and so much more. Russell, whose first book, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, was published in 2020, is the executive director at New York’s The Kitchen performance space, and was previously a curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem. That’s where she first met artist Jordan Casteel. The two friends managed to sync up this past February to talk about the power of images, the importance of slowness, and the meaning of Harlem as home.

———

WEDNESDAY 4 PM FEB. 28, 2024 NYC

LEGACY RUSSELL: Okay, the recording has started. Jordan, part of the reason I was excited to be in conversation with you is because of your immense and gorgeous commitment to different models of Black representation. Having just written Black Meme, where so much of what I’m grappling with is the failures of representation, I’m curious to hear you reflect about what it means to paint Black people? Who is that in service of, and how might that carry us forward?

JORDAN CASTEEL: When I think about Black representation as it relates to my practice, I think about what it means to be alive today as a Black woman—not only in the physicality of Black forms within my paintings, but also in my physicality and my observations of the world. Black representation is ultimately so much bigger than the visual representation of an object in space or a person in space. It is about being alive and acknowledging the spaces around us and the way we have to move through them.

RUSSELL: I agree. And I love that you’re talking about this idea of liveness, because the book starts with a Black kiss, citing the film Lime Kiln Field Day [1913]. In it is an important moment of Black intimacy, a kiss between Bert Williams and Odessa Warren Grey. The scene allows us to think differently about this idea of liveness. What does it mean to feel astounded and inspired by this very ordinary act of love that we have not been given enough of? That has not been provided to us in terms of what we celebrate and center and champion through and beyond the internet. I think this question of liveness is really important, because when I stand in front of your work, Jordan, you are making a choice to represent liveness. And that pushes back at the very assumption of what I would call horizontal Blackness, this notion that Blackness must be on the ground and robbed of its liveness in order for it to be legible to a white imagination. I’m curious, what does it mean to you to put Black and Brown people into the history of painting?

CASTEEL: Your idea of a horizontal Blackness is so true. There is a perception that our Blackness is just lying down to be absorbed, as opposed to being actively engaged. So much of my work is focused on the living histories of what we’re observing and honoring in real time: Who is in front of me? Who are the people engaging in my everyday existence? But also, what are the places, what are the spaces? What does it mean to be actively alive, and confronting that head-on with intimacy? It’s the kiss. To see and feel passion, to give it in a reciprocal form, an act of love and an awareness in relation to one’s body. I think that is the thing driving my practice forward and so much of what you’re discussing in Black Meme.

RUSSELL: I’m keen to hear your thoughts on how photographic representation functions in your process. Or even technology as a whole.

CASTEEL: Technology plays such an intimate, important part. A photo is a stepping stone for me to reengage with a moment in time, as fleeting as it might have been, and then to spend an actual lengthy amount of time with it retroactively, by making the painting. It’s almost like a diary, where you’re taking a second to pause, to think about what is happening in front of you, to put it into words and actually reflect on it longer-term. So it’s a matter of speed and then slowness.

RUSSELL: It’s interesting to hear you talk about slowness. One of the problems with Black representation is speed, and we deserve slowness. I want to bring up a site that has been inspiring to both of us, and that’s Harlem. For me, the whole history of Harlem is a living Blackness, right? It’s a testament to the passion of Black life and the resilience of Black life. When I reflect on the study of Blackness, it intersects deeply with my father who was born and raised in Harlem and was a photographer. It allows for me to think about the model of representation in the work that he did, as someone who spent a lifetime documenting Black people. I know Harlem also means so much to you in terms of your history.

CASTEEL: I can’t help but think of Harlem as being one of my homes. Making a practice that is centered around the people who give me a sense of home and belonging, it feels like giving them their flowers. As a Black woman, I can also speak to the experience of oftentimes feeling invisible, or forced into a certain invisibility. I’m reckoning with my own feeling of invisibility and wanting to give visibility to others—giving me a place to feel seen, and I want to reciprocate that. And I will forever be grateful to Harlem for that. I’m curious, Legacy, when you enter Harlem, do you feel your father’s presence? Do you feel that those photographs, the aliveness of them, reflect on your own relationship to Harlem?

RUSSELL: It’s a wild thing. My father was a Black artist who struggled. I think it’s important to think about the significance of that and who we do this work for and in service to. I lived intimately in adoration with my father as a producer of so many gorgeous and amazing works that live on in his archive, but that in his lifetime were immensely difficult to produce because they were works that really championed Black life in a moment where he himself felt so unsupported as a Black living artist. He made a document of that, that was dense and ecstatic and urgent and necessary, and honored all facets of his growing upward and outward in Harlem, and then as he moved downtown to the East Village later in his life. It’s interesting to ask who we are in dialogue with across the course of our careers. I certainly think I am in dialogue with my father even though he’s no longer in the room with me. His work as a photographer has shaped much of what I have thought about in relationship to this idea of representation. I grew up as a digital native who came of age in an era where so much of our ways of seeing ourselves were reflected back through the electric mirror of our machines. So to be exposed to those images created through the manual processing of photography, which was a physical process, developing the film and going through the contact sheets, all of that—

CASTEEL: The slowness of that.

RUSSELL: Yes, the slowness of the whole process and really reflecting on how you do that work well. Because those images were intended to live on far beyond any of us, with the great hope that someone will see them and care for them. That idea has continued to resonate with me. So when I’m doing my writing and inside my curatorial practice, and my leadership at The Kitchen, I’m constantly thinking about to whom and in what service. Because my audience is not always folks who have been welcomed into these rooms. The mission of the work is about how to expand those points of visibility so that folks feel like they have a sense of belonging, and also, that there is a record of them having been there.

CASTEEL: So that there is an archive.

RUSSELL: Yes. And that goes back to the way you produce your work and the archives inside of archives, and your different relationships to technologies as well as individual people.

CASTEEL: In so many ways, we are a product of the environment in which we are raised. And when I think about my time in Harlem and making work that engages with that community, it is one hundred percent about not only me telling my story and documenting my archive of my life, but also documenting and archiving for other people as well. And so much of that is a conversation not only about what I imagine and experience of somebody, but the way that they imagine themselves. I think the Black imagination is about allowing for our own recognition of our vision and imagination, within the context of somebody else’s.

RUSSELL: Absolutely. I feel like it’s a unique and incredible experience when someone is able to see themselves in a work in a way that changes their view of the world. And maybe then folks will seek out different models of their presence simply because you have presented them with that vision. I also love that Glenn Ligon saying, “Went looking for the art, and we were the art.” That this notion of a Blackness that is decorative, and that is aestheticized, and that is flattened, versus this idea of what is exalted, and celebrated, and centered in its capacity to expand our worldviews—that actually those things have a historic point of being made antagonistic to one another. In fact, I think so much of the notion of Blackness is shaping a cultural view: Blackness as a sort of sticky subject that is intended to change or transform the ways in which we think about what is decorative, rather than thinking about the substance of it as being mapped to real and sustained lived experiences. I’m curious about your foray into landscape and flowers. I wonder if nature can be a different way of expressing a figure when the figure is maybe not in the frame?

CASTEEL: When I think really explicitly about how the landscape has played a part within the context of my practice, it has always been about the situation of us as Black people in relation to the environment. Where do you feel the most safe? And where I am currently experiencing life at its most vibrant and satisfying is my garden. So the landscape is my own full-circle way of acknowledging my own presence within the work very explicitly, even in my absence as a physical form within the work. I feel that a lot of my works that are without a figure are the deepest, most satisfying reflections of self I’ve probably done to date. I’m finding a sense of real peace and joy in allowing myself to sit within the paintings.

RUSSELL: I love that. I guess the last thing I’ll say is that, the fact that we can sustain those aspects of being in one’s garden or being ordinary and slow allows for us to think differently about what we’re due in terms of a culture that should love us and allows for methods of that care to be expanded and manifested with a new language—including the ways in which we shape the images around us. So yeah, just ending on that thought. I’m really grateful to you and have immense admiration for your ongoing work and vision.

CASTEEL: It’s so mutual. It is your vision that even brings us here today, and your ability to see and articulate the way that we are creating, and it starts with your ability to see the slowness of your father’s process in the studio and archiving that. You’re archiving it for all of us. So, thank you.

RUSSELL: I’m going to stop recording.

———

Hair: Andrita Renee.

Makeup: Rose Grace using Kylie Cosmetics at Forward Artists.

Nails: Nori using Chanel Le Vernis at SEE Management.

Photography Assistant: Jordan Hundelt.

Fashion Assistant: Meekal Tedros.

Production Assistant: Kiernan Francis.