OPENING

Cows and Butterflies at the Opening of David Peter Francis in Chinatown

David Pagliarulo, photographed by Emily Sandstrom.

When I asked David Pagliarulo how he was feeling on the opening night of his new solo gallery, he told me it felt like prom. “When all the people you know are in one place, it’s usually either a wedding or a funeral,” the 28-year-old said. “And prom is both of those things.” David Peter Francis, Pagliarulo’s brand new outpost, is nestled on East Broadway, on the third floor of an old, abnormally ornate building with towering ceilings and oversized windows. Simply put, the perfect space to take in art (and light). After serving as the director at Marinaro Gallery, Pagliarulo decided to open his own space so he could spotlight the work of artists who’ve been overlooked but are nevertheless dear to him. Though the throngs of people at his opening last Thursday mostly weren’t wearing gowns or tuxedos, the vibe was certainly prom-like; one sculpture even fell victim to the roaring crowd. But before things got out of hand, I visited the gallery to talk to Pagliarulo (and the building’s super, who made many surprise visits warning us of a leak) about the works included in the gallery’s inaugural group show, Butterflies, including a haunting Peter Hujar portrait of a cow and a playful painting by Latefa Noorzai.

———

EMILY SANDSTROM: How did you decide on this spot?

DAVID PAGLIARULO: When I was first looking around at spaces, I wasn’t quite sure about which neighborhood. But when I saw this space, it was really the lobby that first got me. I was like, “This is unbelievably camp for Chinatown.” When I got up here, the space was originally this unit and the one next door, blown out, but when I was looking, they told me they were planning on splitting the units up. I was like, okay, I think these proportions work correctly. The only architectural intervention I put in was this wall. It needed multiple sidelines and corners to spark conversation between the pieces. I like that the space feels like an old style New York loft, but it’s still situated downtown and nearby a lot of galleries that I love. I’m close with Isaac [Lyles] and Geena [Brown] from Lyles & King, and this neighborhood is very familiar to me. My former job at Marinaro Gallery was around the corner too, so I know all the good lunch spots.

SANDSTROM: You made a great choice. It’s beautiful in here.

PAGLIARULO: Thank you. I first started talking to the artists about this idea about a year ago, and that’s when I decided to pursue it. The impetus for the show really came from a lot of these friends and peers and artists that I’ve loved and admired but haven’t necessarily gotten the gallery airtime that they deserve. Then, from a curatorial perspective, everyone started crossing over around these conversations. It became very meta about beginnings, and what that feels like almost when you’re about to jump over the cliff. There’s always anxiety to it, but then there’s joy and excitement.

Colleen Billing, Conduits, 2023, glass, silicone, electroplated organic material, centaurea, foraged plants, 41 x 9 x 8 inches.

These sculptures are all filled with silicone. They act as a false representation of what it is in a sense, because it looks like muddy water. These are all medicinal, the plants and flowers that she forages. She electroplates some of them at the end, so she’s thinking of them as stomachs that are exploding with electricity. When we were installing, we were talking about them as a bunch of swans that are gossiping together on a pond. There was a conversation within them about connectivity, but also with an ecstatic feeling of movement. When we placed these, they really corresponded with Kathryn’s painting.

Kathryn Kerr, Black Sails, 2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 54 x 66 inches.

Kathryn [Kerr’s] one of my favorite painters working right now. Her imagery is so layered with reference, but every single painting she makes is completely different from the next. She had a show last Spring at Lomex. That show felt like a chorus of different people singing the same song together. All the paintings were really different but spoke to each other. But for this one she said, “I wanted the feeling of pirate ships crossing in the distance.” And I thought, “I love when a painting is about that, specifically.”

Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez, Mirror (David), 2024, archival inkjet print, 16 x 20 inches.

Around this corner is Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez, who’s going to do the solo show after this. His practice is within photography, but also in archival imagery practices. One of his main bodies of work was when he was in Mexico City around four years ago. He was in an antique store and he found this giant pile of vernacular photographs of what seems to be like five years of this young gay man’s life–

SUPER: Hi.

PAGLIARULO: Uh, hi. How are you?

SUPER: [Inaudible]

PAGLIARULO: Okay. Oh, that’s not good. [Intermission] Okay. All good. So he found this entire archive of vernacular photos. From what it appears, it’s like five years in this young queer man’s life. Over the course of the years he’s had this archive, he’s been slowly constructing the narrative of this person through those photos, with his own photography mixed in, to provide a world-building moment around the images. It’s almost a way for him to inject an examination of identity without having to put himself into it specifically, because of the observations that he comes up with.

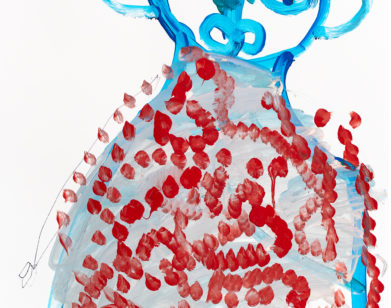

Latefa Noorzai, LN 510, 2023, acrylic and pen on paper, 44 x 30 inches.

I love Latefa [Noorzai]. She works out at Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland. They provide studio space and resources to artists with physical and mental disabilities. Latifah actually did a story with Interview a few years back where they asked her to paint a bunch of Spring/Summer runways, because all of her work is based on fashion illustration. She looks at fashion magazines and paints herself in these beautiful costumes. She’s from Afghanistan and she immigrated to the US but doesn’t speak any English. She speaks Dari, which is a dialect in Afghanistan. Creative Growth have a translator that helps her communicate with the entire staff, and they provide her with the space to make these paintings. They’re all so fun and immediate. I’m really happy to have it in the show.

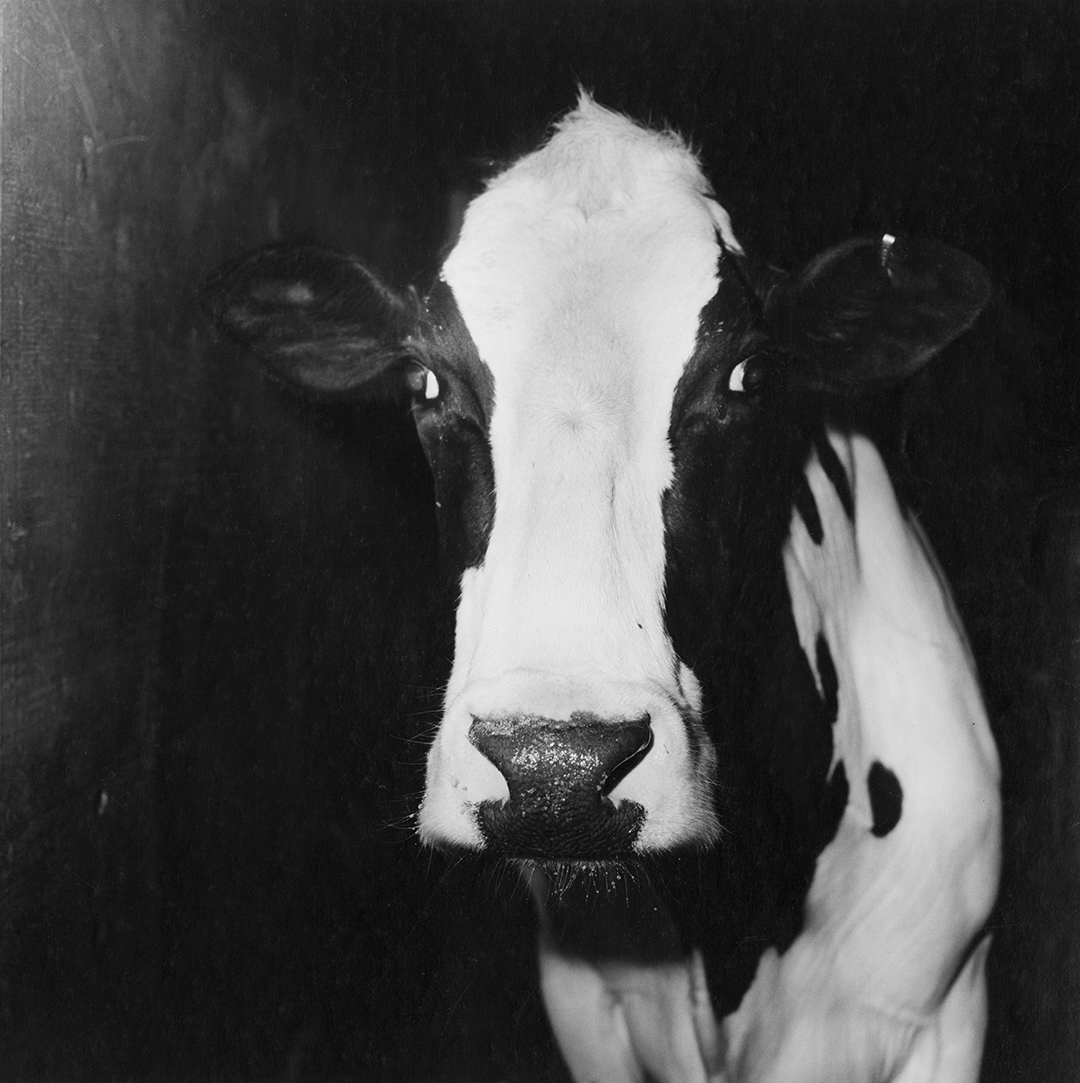

Peter Hujar, Cow at Night, 1978, silver gelatin print, Framed: 23 1/4 x 22 3/4 inches.

PAGLIARULO: If I had a Mount Rushmore of artists, Peter [Hujar] is on it. I went to visit the archive a really long time ago on a whim. I sat with the archivist, Stephen, and talked for a really long time. I asked him what he thought was truly representative or important in his body of work, because everyone knows Peter’s photos of gay guys naked. But Stephen said that the cows were the most representative. He was telling me the story of when they were driving through rural Pennsylvania and Peter pulled the car over at this field full of cows and was like, “I need to go photograph them.” And instead of just getting back in the car after photographing them, he stood there for like an hour and talked to all of the cows and got to know them.

SANDSTROM: Oh, woah.

PAGLIARULO: I know. I need to know what the cows said to him. [Laughs]. But that really put his practice into perspective for me. Peter’s work to me has always been like meditation about a time running out, because he died of AIDS relatively young and before anyone really was paying attention to his work. And the cows feel very prescient alongside that. Having this in here is buck wild and so cool.

SANDSTROM: This cow is haunting, especially the closer I get.

PAGLIARULO: It’s scary. This is a lifetime print, so you can see the detail of the sweat on the nose and the whiskers. Peter photographed fashion too, so he knew how to make people look beautiful. So there you go. Come on, cows.

SANDSTROM: Should we sit?

PAGLIARULO: Yeah, let’s sit. I’ll move my bagel. It’s good to start with a group show because it keeps the general vibe in the air, but also allows certain connections to be built as far as what it all means and what we’re going for here.

SANDSTROM: How long have you been in New York?

PAGLIARULO: I’ve been here for six years. And then this space was another five-year lease and I thought, “Let’s go girls!” Before this I was in grad school in Paris for about a year. I was in a visual culture program and when I got to New York and I was like, “Well, I can only work in a museum or a gallery.” Before this I was the director at Marinaro. I got to a point where I felt like if there was a time to do this, it was now. Because I’m still relatively young and energetic. And the impetus for this show was that I knew a lot of artists that weren’t getting a lot of airtime in the gallery world. I thought, “Wait, this work is amazing, what are we doing? Why are we limiting ourselves to a specific thing?” I loved what the group of artists around me was doing, but I found they didn’t really have a context. And I thought, “Well, I have to make this context.”

SANDSTROM: Tell me about the name of the show, Butterflies.

PAGLIARULO: It was one of those where I was thinking of titles and I was trying to describe that exact feeling of nerves with something that’s very beautiful. But there’s no butterflies in the show.

SANDSTROM: I love that. Well how are you feeling about the opening otherwise?

PAGLIARULO: It feels like prom. When all the people you know are in one place it’s usually either a wedding or a funeral. And prom is both of those things.But I don’t think I’ll do a prom queen speech at dinner.

SANDSTROM: You absolutely should.

PAGLIARULO: Yeah. I could get a sash. I was thinking about doing a boutonniere thing. Maybe it can be prom in spirit.

SANDSTROM: Also, how did the name David Peter Francis come about?

PAGLIARULO: Well, my last name is very Italian, complicated and unpronounceable. So I wasn’t going to force everyone to try to pronounce that. My first name is actually Rocco and my middle name is David. And it couldn’t be Rocco because this is not a pizzeria. So I took my middle name, my dad’s middle name, and my grandpa’s middle name, so: David Peter Francis. It sounds like a fake art dealer name. It’s also funny because my parents aren’t art people at all. We went to MoMA one time and we were in the room that Starry Night was in. My dad was like, “Why are they crying around that painting?” And I was like, “Oh, that’s Starry Night. Like, the second most famous painting in the world.” So we looked at it for a while and he was like, “It’s alright.”