Collier Schorr Explores Evidence versus Intimacy in Paul’s Book

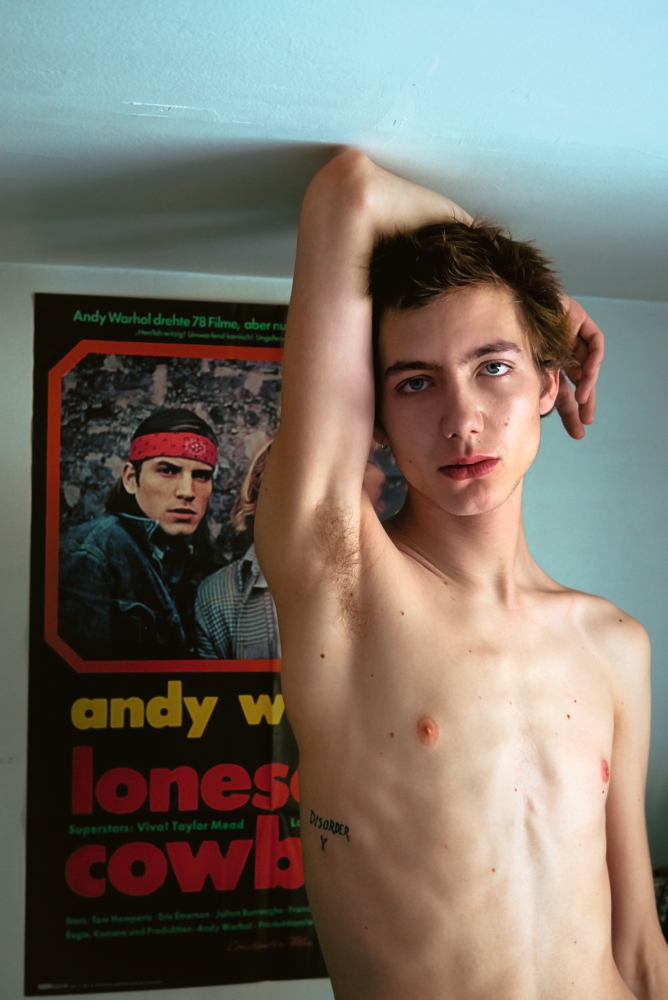

Collier Schorr. “Lost Cover, Re-Edition #5, 2016” from Paul’s Book (MACK, 2019). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

For two years, photographer Collier Schorr visited the artist and model Paul Hameline at his parents’ house in Paris while in town for business. The two would rendezvous to catch up and take pictures, free of any professional motivations. This ritual evolved into Paul’s Book, a collection of Schorr’s photographs of Hameline, interspersed with fragments of text that result in a visual diary of sorts, documenting an ongoing conversation between the two artists across time. First seen in Re Edition magazine, the photographs also appeared in Systematically Open?, an exhibition at the LUMA Foundation in Arles, before reuniting in Paul’s Book. The images are startlingly intimate, with Hameline floating effortlessly inside his bedroom, unencumbered by any expectation of what the final image may be. The book illuminates the particular relationship between Schorr and Hameline, one cemented in a type of trust that lies beyond the traditional framework of photographer and subject. Interview caught up with Schorr, a frequent contributor to the magazine, to ask her about Paul’s Book and why she expects her reader to come ready to argue.

———

MARK BURGER: This book feels very intimate to me. Lots of bedroom spaces, lots of really stunning portraits.

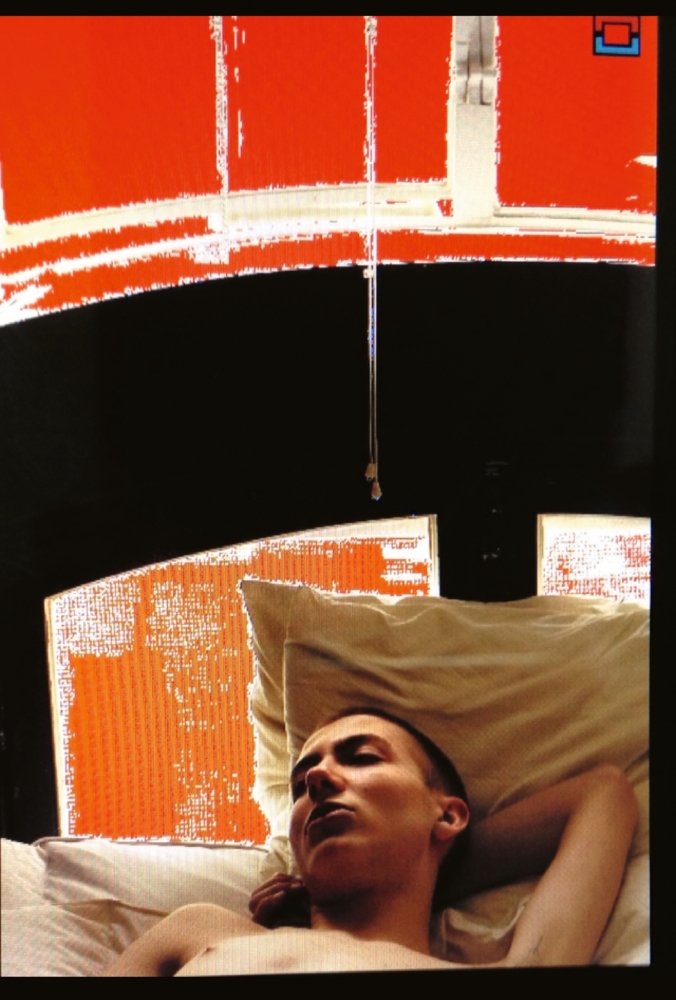

COLLIER SCHORR: In a lot of editorial shoots, there are set up bedroom scenes, especially for actors and musicians. And it didn’t occur to me until you just said that, that one of the nice things about shooting at Paul’s house was there was like an actual bedroom. It wasn’t set up–it was like a natural place to be, undressed or laying in bed. I think both of us responded to the idea that we weren’t in a fashion shoot, and that everything that was in the pictures was sort of part of his life. It’s hard to fake it all, all the time.

BURGER: What were you thinking when you first started on this project?

SCHORR: I was simply thinking it would be so nice to make pictures without any point, or without any kind of goal. It was easy because Paul’s house was a block away from my hotel, so we set up a kind of routine. I would go there to shoot advertising clients mainly, and I would usually go to his house the day I arrived, because that would be the day that I had off. We did that a couple of times, and we were so happy with the pictures. I suggested that we ask Re Edition if they wanted to run them, and we could take some more and they could send just a few fashion credits, and I picked out stuff that made sense for Paul. I also brought in this kid named Edith, because I’d seen her around and thought she was really cute and I liked the idea of having a kid mixed in. So we did maybe two more of those shoots, and I put it together, and I, for some strange reason, mixed in other things. I wanted to mix in historical pictures I had done that seemed to fit with the idea of casting that was happening at the time. The cover of the book is called “The Lost Cover” because we had a cover and we lost it. And when we did, I said to Paul, “I’ll make you a book instead.”

BURGER: What was it like working with Paul on this project?

SCHORR: We immediately came together, and we had a lot of shared interests even though we’re completely different people. I really liked talking with him, and I found the whole set up being in his parent’s house really relaxing. I think the intimacy comes from actually people being relaxed, and I’m not sure that’s something you see all the time. I don’t think that people being close sexually necessarily represents intimacy. I think it’s actually being relaxed and not having enormous expectations, and trusting that together you’ll make something that you want to look at again. I had no idea at the time that it could be so much. And I don’t know if it is so much, it just feels like it answers something.

Collier Schorr. “Golden Paul, Paris, 2016” from Paul’s Book (MACK, 2019). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

BURGER: I like to think about what it means for a photo to be on a wall in a museum versus inside of a magazine. Who’s seeing it, how they’re seeing it, and so on. Do you ever think about that with your photography?

SCHORR: I used to, when my audience was so specifically the art audience. I was sort of hyper-aware. I remember a period in which someone had told my dealer that I did too many pictures of boys, and I doubt they said that to Jack Pearson or Wolfgang Tillmans. There was this idea that somehow I was either mining territory that didn’t belong to me or I was mining a territory that was useless. I think that in fashion, I had less self-consciousness about that. And at the same time, I had more access to women who wanted to be photographed. It also created a situation in which I could work with women in this really consensual way, where there was a shared agenda. It wasn’t like I was an art photographer approaching women to make a picture they might not ever see or might not ever benefit from.

I think there’s an effort in the book to use Paul’s body as a way to talk about different kinds of pictures, both seductive and a little bit terrifying, evidence versus intimacy. It wasn’t like how deep inside you could get with somebody, it was more like how many different ways can you talk about portraiture or documentary with this one figure. The reason you can do so much is because Paul was himself really aware of picture-making and photography. It wasn’t just that I was looking for him to become something. He was also looking to become something.

Collier Schorr. “Paul in his bed, Paris, 2016” from Paul’s Book (MACK, 2019). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

BURGER: Was it your intention from the beginning to pair some of the images with text, or was that something you developed later?

SCHORR: Some of it happened when I was preparing it for the magazine. I kind of get triggered or startled by a picture, and then it becomes something else. I want to bring some kind of secondary text into it to illuminate the picture, so that people have an idea of a second way that I had seen it. There’s the picture, and then I’d get home and I think, “Oh, this is sort of about something else.” And that’s what I love about magazine work. That you can, on the date it’s due, have an epiphany and add something. In a way, it’s like being an installation artist where you can come in the morning of the opening and move things around. Just as an aside, Paul really reminds me of the kids I used to shoot in Germany.

BURGER: Oh really?

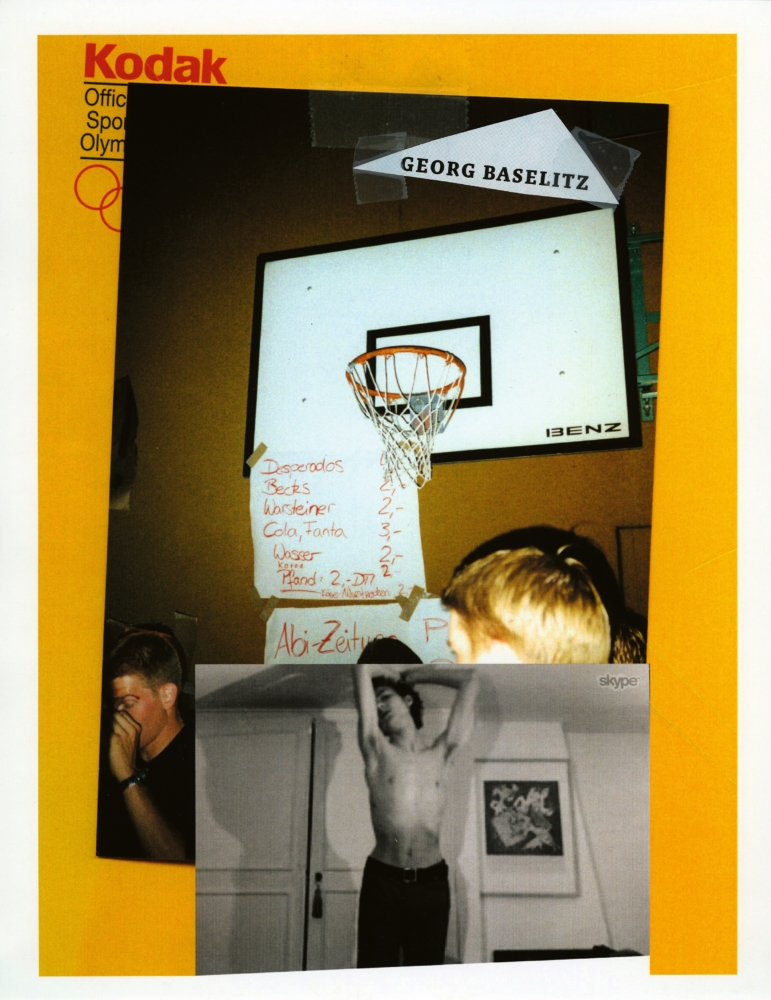

SCHORR: Yeah, because he’s scrawny and I think he’s super handsome, but he’s not traditionally handsome. And that’s how I feel about the kids in Germany. The kids I picked for the most part, I thought kind of special and interesting and they weren’t the most handsome boys at the swimming pool, but there was something about them that was dramatic in some way. I think that the attention kind of renders them handsome, but ultimately a super handsome boy, somebody who was just like blue-eyed and blonde haired and perfect, could never carry that book. A perfect model could make one great story, but an interesting person could fill a book. But he also has company, because when I make a book like that I always want there to be a sense of a supporting cast or a chorus, an extra who’s suddenly in the picture.

BURGER: Wow.

SCHORR: I know. I’ve been thinking about it.

BURGER: In a novel, having a cast makes sense. But in a photography book, it never occurred to me to think of it as a story with a cast of characters, so to speak.

SCHORR: Yeah. It’s just like maybe they only have one line, but it sort of sets up something to happen.

BURGER: Also, it relates to the book being a diary of sorts.

Collier Schorr. “Paul/Abi party (Desperados), Re-Edition #5, 2015–2016” from Paul’s Book (MACK, 2019). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

SCHORR: It feels that way in that I traveled to some place and I went someplace else. I can look at those pictures and remember that time. Or maybe it’s like, “Dear diary, I met this guy today. He seems really special. I’ve got to get to know him.”

BURGER: Exactly. Sort of like one line or one entry for each photo.

SCHORR: Yes. My agenda is to make it deep. It should be something that you can’t go through quickly and forget. Most of my books are a bit like novellas. I can see when I watch people look through them, it’s so slow. At some point, I’m like, “Okay, get to the end of that book already.” But you can’t go so quickly through it because it changes. And then all of a sudden you’re thinking like, “Well, what’s this still life for Frank Ocean doing in here?” It’s a reading list. That’s why it’s there. Then you think, “Well, are some of these pictures a reading list?”

BURGER: Wow.

SCHORR: I know. There’s an expectation that you should be a smart reader, that something has been gathered for you to investigate, and I think that a lot of people who get books, that’s just what they want. They want to hold it, they want to look at it a couple of times. They want to kind of argue with it.

BURGER: Whereas with a photography book or an art book, people think, “Oh, this is the image. Okay, I’m going to look at it for a second, then move to the next one.”

SCHORR: And put it on the coffee table.

BURGER: Exactly. It’s like, the book itself–it taking up space is what makes it, instead of the content that’s inside.

SCHORR: I aspire to people not being stupid. And I have the same requirement for myself, which takes a bit of effort.

BURGER: I think people don’t give photography books the respect that they deserve.

SCHORR: I also think that the book is not about me. It’s about a lot of other things. I have other ways of talking about myself.