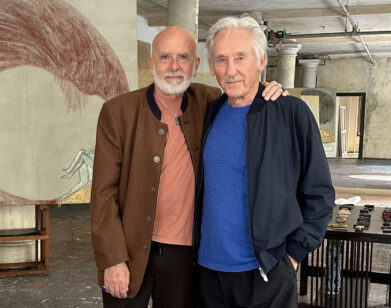

Christopher Wool & Richard Hell

Christopher Wool is widely recognized as one of the world’s most important painters. His first one-man show was at the legendary Cable Gallery in 1984, and since then, he has showed his bold word paintings; edgy, energetic pattern paintings; and revolutionary, quietly startling manipulated abstract paintings in galleries and museums around the world. Richard Hell was one of the originators of punk music. He played in the first wave of bands that brought attention to CBGB and became famous in 1977 as the auteur of the album Blank Generation. He retired from music in 1984 and built a reputation as a writer to rival the one he made as a musician. His most recent novel is Godlike. Richard and Christopher have now collaborated on a series of word images. Glenn O’Brien, who goes way back with both of them, met the pair at Wool’s studio on the far Lower East Side of Manhattan to discuss this. PSYCHOPTS is a book of 57 pictures by Wool and Hell, published by JMc & GHB Editions this month. Publication coincides with an exhibition of a portfolio of nine silk screens of these images, along with six collaborative drawings, at John McWhinnie @ Glenn Horowitz Bookseller and Art Gallery in New York City (johnmcwhinnie.com). Christopher Wool will show new work at Luhring Augustine in New York City, May 10-June 14.

Glenn O’Brien: How do you know each other?

Christopher Wool: You want to tell?

Richard Hell: We first got acquainted when Christopher called me up about using some words. This was 1997 or 1998. He wanted to ask my permission to use the words that I’d written on my chest on the cover of my Blank Generation album, as the text for a word painting. Which of course he didn’t have to do. I mean, that was really courteous. It’s not like I own those words.

CW: I have taken things and made paintings without having permission. But in this case, I wouldn’t. Oh, and then it turned out I missed something when I painted Richard’s words.

RH: I went over to Christopher’s and saw his painting. On the original album cover I’m standing there holding my jacket open, and I don’t have a shirt on underneath. And in Magic Marker I have across my chest, in all caps: YOU MAKE ME ____. It was just a blank. An underscore. Anyway, when I saw the painting, Christopher had filled up its entire surface with “YOU” on top of “MAKE” on top of “ME.” And I said, “Wait a minute. Where’s the ‘blank’?” And he said, “Well, how about I just leave a space at the bottom?” Which is what he did. There’s an empty line below the last word. So it worked out great. I was impressed by how casually he was willing to make what seemed like a major change. It seemed gallant. And like . . . self-confident, and suave. The guy was a gentleman and an artist.

GO: Then what?

CW: Richard was publishing a series of poetry books. CUZ Editions.

RH: They were more like pamphlets really.

GO: I have several. Rene Ricard with art by Robert Hawkins. . . .

CW: They were poetry and art collaborations.

RH: Well, not necessarily, but many of them included drawings. But I asked Christopher if he would do the cover of mine. It’s called Weather.

CW: Explain what Weather is. The book is actually all the versions of one poem as Richard was working on it.

RH: Well, there was choice involved.

GO: I thought they were variations on a theme.

RH: But the way it actually happened was that they are states of writing a single poem. I realized at a point, as I looked over the drafts, that they made a poem I liked more than any of the drafts separately. Christopher had actually done the same thing, though I didn’t know it-and neither did he, since he didn’t know the history of Weather, and in fact didn’t publish his until a few years after my book. He did a book of the Polaroids he would take of his paintings as he went along, pictures at various points in the process of making a single painting.

GO: Are these poems in the order that you wrote them?

RH: Yes.

GO: And Christopher, what order are your Polaroids in?

CW: Actually they are almost in reverse order. But it’s edited. The thing is that the discarded stage in retrospect sometimes looks more interesting than the direction I took in the finished painting.

GO: I used to sit with Jean-Michel Basquiat when he was painting, and he’d cover up a section of finished work with paint and I’d think, Oh, God, he’s ruining it.

RH: There’s a movie of Picasso painting where you see a canvas go through all of its forms, like stop-motion photography. It seemed completely arbitrary where he stopped. It seemed like there were 30 good paintings in there.

CW: With Jean-Michel or Picasso, the fact that they could do it so easily is what makes the work, in the end, so great. They had absolute fearlessness. If you’re not fearless about changes, then you won’t progress.

With Basquiat or Picasso, the fact that they could do it so easily is what makes the work so great. They had absolute fearlessness.CHRISTOPHER WOOL

GO: Richard, did you know Christopher’s work before he asked permission to use your words?

RH: I didn’t really know it. It’s funny, when I first saw his stuff, I was kind of aghast. When I first saw his word paintings, I thought: I can’t believe what they’re getting away with these days. [laughs] But I grew to really, really love them, and all of his stuff. It’s really interesting with art-movies too, but art especially-to see how your attitude toward artists and works and your level of appreciation of them is always shifting and changing over the years. That’s happened to me with a lot of artists, more so than other media, and it’s part of what makes art so interesting.

GO: I remember, as a teenager, hearing songs like “Paint It, Black” for the first time and thinking, Wow, there is something really wrong with this. Two days later, it was the greatest thing I’d ever heard. At first you have to be insulted, almost

RH: Right, right. Not too long ago, I saw that somebody said something like, “If I hate it, I know I like it.” [laughs] It might have been John Waters

GO: Richard, what other contact had you had with Christopher before this current collaboration?

RH: I wrote about his photography for the Taschen book. Because his photographs blew me away. And he asked me to do something for this magazine Whitewall when they wanted an interview he didn’t want to give. So I wrote “What I Would Say If I Were Christopher Wool”-like a bogus interview.

CW: But this has been a big, long collaboration. Besides the book, there are prints and drawings.

RH: For about a year, we’ve been getting together every week. Though he’s been away for little periods, and I’ve been away for some periods.

GO: What was the process?

RH: I had pairs of words that we wanted to make into images. What the words have in common is that they look alike, and that’s it. We played around with how to put them together, how to make images out of them.

GO: The way people read is all about a kind of shorthand. You’ll see three letters, and you’re going so fast that you kind of assume what it is.

CW: Yeah. And then sometimes you catch yourself. That’s the amusing part of those pairings. And everyone does that a little bit-they think they see a word when they read something else. Anyway, we started with 13 pairs of words. Our project didn’t have anything to do with changing those words, or reassessing those words. They were just images we started with.

RH: Right. I would find that my eye jumped to a word on a page because I was anticipating something. My eye would jump somewhere and it would turn out to say “stuns,” and I would realize: Wait a minute, I was expecting “anus.” Obviously my eye jumped because it’d caught a glimpse of a word that was charged for me. I called the series Psychopts because of that. They’re about making something to look at that has these other things going on too. To me, they’re funny-though they’re in your face, too. It was so great to work with Christopher. His eye is impeccable and he was so generous.

GO: Do you guys think the age of poets collaborating with painters is over?

CW: Well, we’ve just begun!

GO: It’s weird what’s going on with the world of poetry, with the influence of the poetry slam.

CW: It’s become more performance-oriented and less book-oriented. Is that right?

RH: I don’t know. I mean, it did kind of peak in the ’50s and ’60s-Frank O’Hara and Larry Rivers, the abstract expressionists, and then all of the St. Mark’s poets with Joe Brainard and George Schneeman.

CW: As for poets doing this kind of collaboration, it doesn’t seem that it’s dead, but that maybe it’s skipping a generation or something.

RH: Poetry’s always dead, you know? You don’t realize how good poetry is until 15 years later.

CW: Despite all the attention paid to art right now, you could easily argue that it’s dead, too. But art’s not dead.

RH: There’s a lot going on among young poets. But it’s not all in New York anymore. It’s more spread out, like alternative music or something.

GO: Art-making got decentralized. People don’t all come to New York anymore. Because of rent.

RH: It’s really hard to figure out how you can mix words and images to give you a third thing. Not just two things side by side. It’s great if you can get them to somehow expand on each other, like the way W.G. Sebald did when he used photographs in his books, or Breton did, with -photographs, in Nadja.

CW: The problem is: If you take text and image and you put them together, the multiple readings that are possible in either poetry or in something visual are reduced to one specific reading.

By putting the two together, you limit the possibilities. Text and image don’t always work together in the way music and song lyrics become part of each other.

RH: There are great exceptions though, like the Sonia Delaunay/Blaise Cendrars “The Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jehanne of France,” where the poem is printed multicolor in one 2-meter-long accordion fold, and she does watercolors lightly all around the text. Or the outrageous, perfect, exploding translation that Ted Berrigan did of “The Drunken Boat,” which Joe Brainard then drew as a cheapo stapled mimeo pamphlet. Brainard copied out the words in his hand and drew pictures around them and opposite them to make a completely integrated work.

GO: I think, at best, collaboration is like dub music in reggae. The artist remixes. They’ll take the finished thing and then deconstruct it.

CW: And hip-hop came out of that.

RH: The major change is that we live in a state now where media is our nature. It used to be that artists thought of nature as their environment. Now media is our environment. It has been for the past 50, 70 years. It’s what you see on TV, on the computer, what is in the magazines and newspapers. That’s the environment now, rather than woods and hills and oceans. And so that’s what you make your art out of.