OPENING

Christopher Udemezue on Ghost Towns and Goth Sensibilities

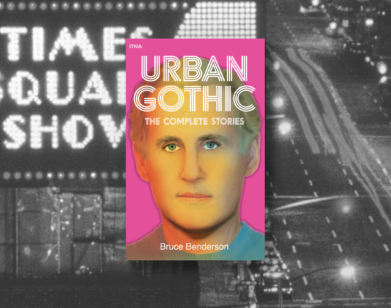

For Christopher Udemezue, goth is more than a phase—it’s a frame of mind. When the artist and RAGGA NYC founder was introduced by his friend, fellow artist and former goth kid Juliana Huxtable, to Leila Taylor’s book, Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul, it was like he’d discovered a field guide to piecing his interests together. The result was in this moisture between us where the guinep peels lay, Udemezue’s newly-opened show at Ryan Lee Gallery: a lush series of images directly inspired by travels to his ancestral homeland in rural Jamaica, displayed alongside historic bronze figures by Harlem Renaissance-era sculptor Richmond Barthé, who also resided in Jamaica for decades. “I’ve been thinking a lot about island goth,” Udemezue says. “On the surface, it’s all bright colors, but […] there’s this ghost in the room at all times.” When Huxtable and Taylor joined him after the show’s opening, they peel apart all the layers of goth sensibilities in the diaspora, from Midwestern ruin porn to his family’s haunted house. “The container may be a horror film, but it’s very much a love story.”

———

CHRISTOPHER UDEMEZUE: First of all, Leila, I want to give you your props for such an amazing book that Juliana put me onto that ushered in my show at Ryan Lee Gallery in many ways. Thank you.

LEILA TAYLOR: Thank you. This is an incredible opportunity. As a writer, I kind of live in this bubble where it’s all in my head, so seeing what I do actually affect other people has been really, really satisfying.

UDEMEZUE: Juliana, how did you even find the book?

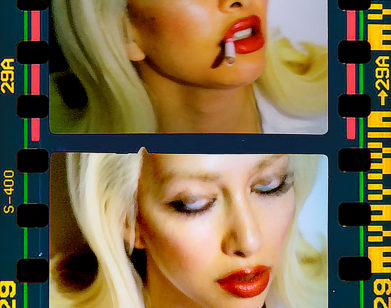

JULIANA HUXTABLE: I followed the publisher on Twitter and I earmarked it. I had been working on my last solo show in New York where I was thinking about what counter and subculture means. I was specifically thinking about a goth sensibility and what it means to authentically inhabit that, especially now that so much of countercultural identity is accused of being reduced to just aesthetics. In that show, I really thought about ways in which both Blackness and transness inhabit spaces that have a lot of overlap. One of the characters in the show is this trans-species bat goth character, and they’re all kind of autobiographical. There were some lines of inquiry that the show brought up, and during lockdown I got a copy of your book and it just totally blew my mind. It was one of those books where I didn’t even know I needed it. What I loved about it is that it’s a journey into the gothic itself while framing what we think of as gothic. Christina [Udemezue is also known as Neon Christina Ladosha], you can probably corroborate this, but in the 2010s and 2020s, we’re still dealing with, “Oh, the Black kids are at the goth club,” and it feels kind of anachronistic. I had so many conversations with Christina about the forms of social anxiety and dissonance that can produce. It was truly inspiring.

TAYLOR: I’m blown away, honestly.

UDEMEZUE: I mean, to tag onto that, obviously the world has been through a lot with the pandemic, but as a group of friends we’ve also dealt with so much. I hate the word trauma, but aggressive life-altering issues, from death to death scares to relationship deaths. There was a lot of morbid energy around me. I found myself having this 16-year-old me living for a Marilyn Manson moment again, on a spiritual level. It was nice to have this guide to tie all my interests into one place.

TAYLOR: It’s interesting that you mentioned the aesthetics of goth and how it’s easy to have a surface understanding of what this subculture is. I got into this pre-Hot Topic and pre-internet, so I wasn’t really shopping for a ready-made outfit or looking at goth makeup tutorials on TikTok. Goth-ness for me was always about being open to and curious about the macabre, and death in particular. And then there was the music, like Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure and all that, which had this aesthetic attached to it, but I never looked the part at that time. I had to let go of goth-ness being a particular look from the get-go, ’cause at that time it was pale skin and Robert Smith hair. I had to make up my own look as a projection of what this meant to me. I remember being little, and there was a cemetery near our house, and we used to play a funeral. I remember there was an open grave someone had dug, and we went there and we’re taking out the dirt and making mud pies, ’cause it made really good mud pies. And then everyone would pretend to be the corpse and we’d cry over them. I mean, slumber parties were freak shows. It was all about hypnotizing people, light as a feather, stiff as a board. That sensibility has lasted so long because it’s so malleable, and it goes beyond one particular band or genre. It’s a frame of mind. It’s not just an outfit or a kind of makeup.

UDEMEZUE: I’ve been thinking a lot about island goth. The literal sweet tooth of this globe came from so much death, and it’s the most morbid and ghastly thing you can think of. On the surface, it’s all bright colors, but in Jamaican Patois, “ghost” is “duppy,” and there’s such a heavy duppy energy in Jamaica because there’s so much pain that still exists. My grandma—this can be on the record, my grandma won’t read this—when there’s infighting in the family, they’re like, “You put voodoo on me,” and it’s like, “Girl, y’all are just fighting. Put the cigarette down.” There’s this ghost in the room at all times, and reading your book made it all make sense because Black people are kind of in proximity to horrific things at all times, but there’s still this nuance of beauty and romance.

TAYLOR: Not only that, but there’s the idea that a ghost or a spirit isn’t necessarily a bad thing. What we automatically equate as scary and evil on one half of the globe could be someone watching over and protecting you on the other. We have a very narrow view of the spirit in this country. So I’m particularly interested in your work because of this connection to mythology. And your band, Juliana, that song…

HUXTABLE: “Pretty Canary.”

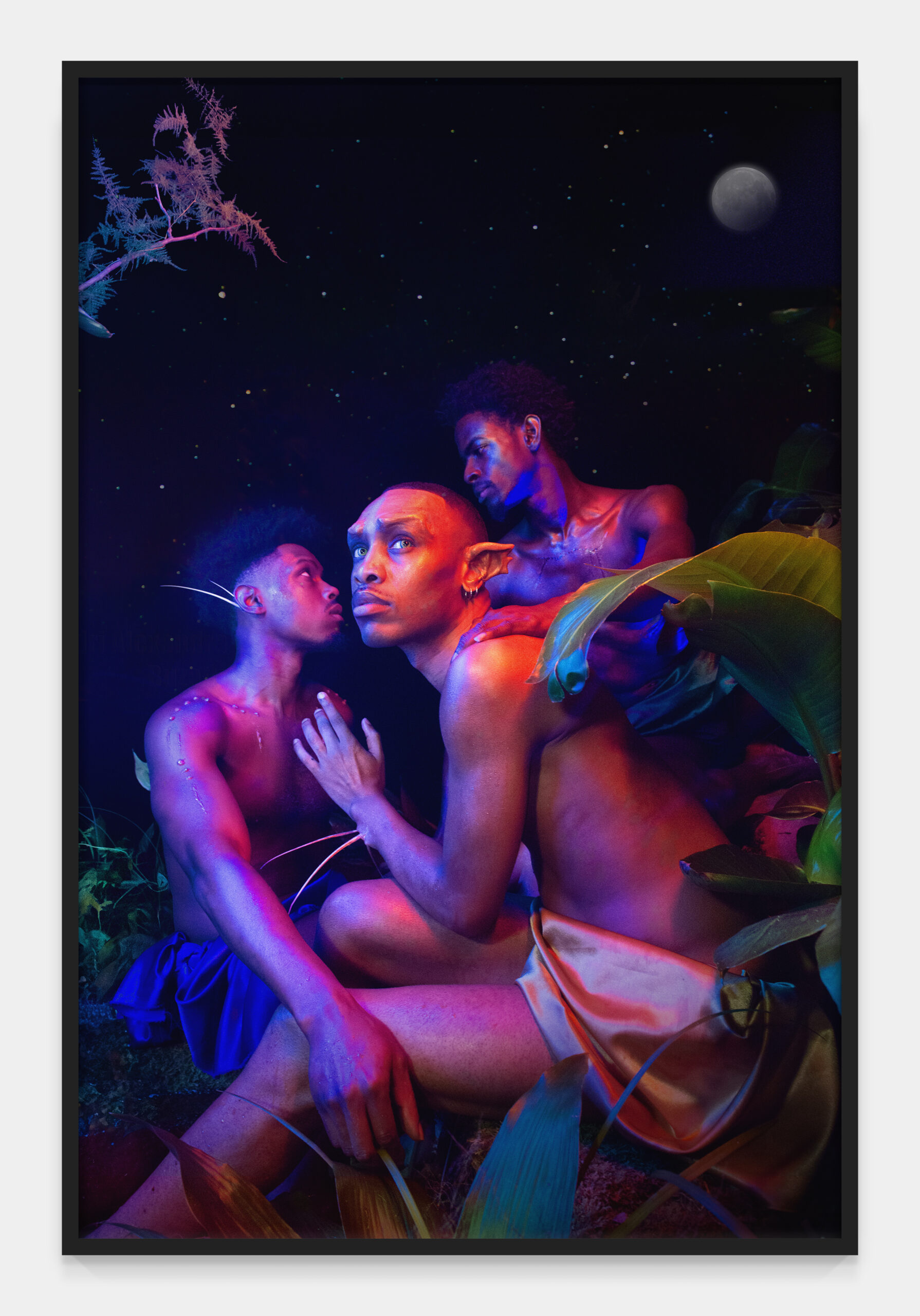

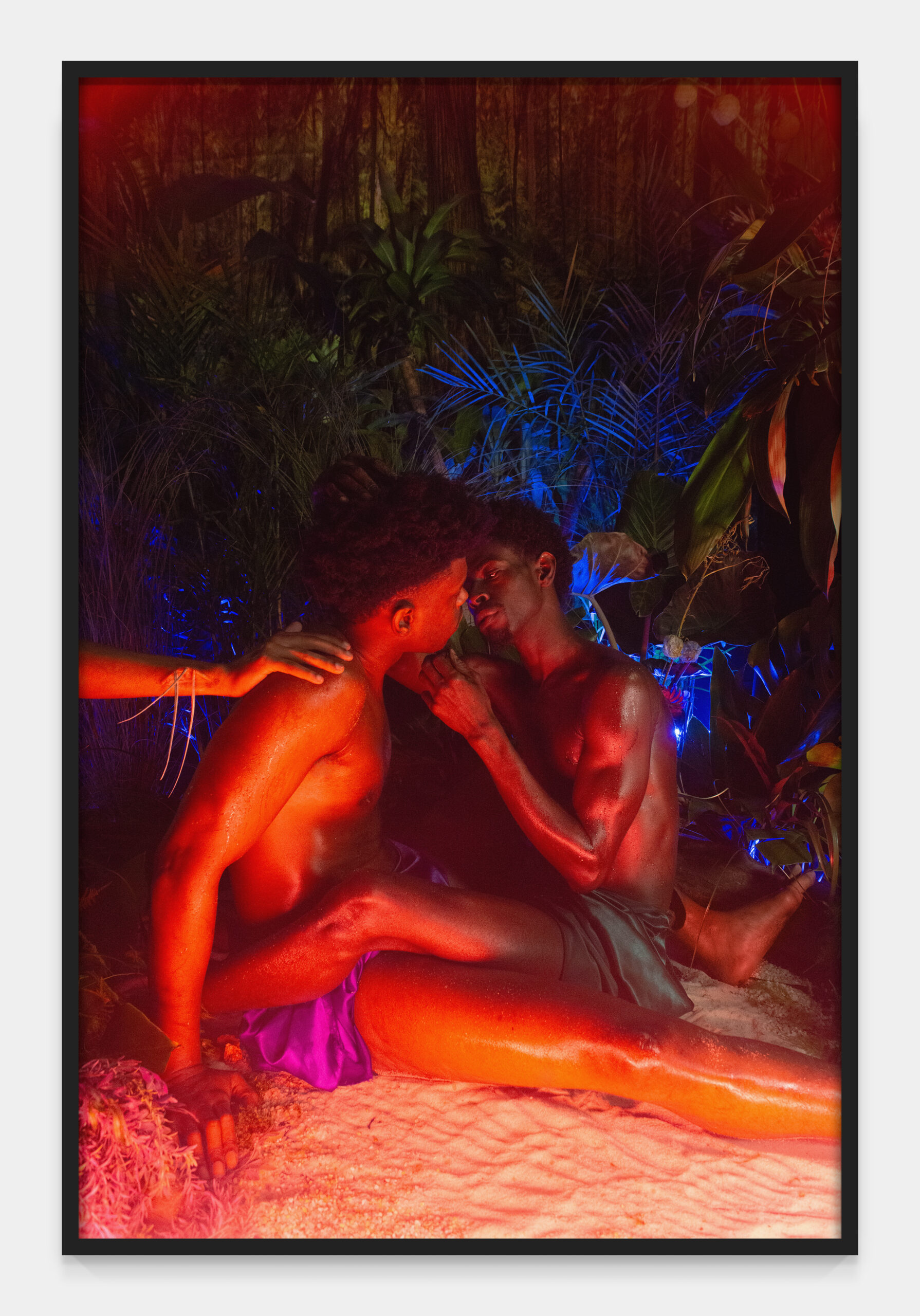

“a tenderness when I was low and a touch on the side of my waist on days like today. a voice_ something brought us to this space” (2024), Christopher Udemezue.

TAYLOR: I have been listening to that.

HUXTABLE: Oh my god, I love that.

TAYLOR: I’m intrigued by this music. It’s also about drama and glamor, it’s not just about mourning and sorrow and trauma. It encompasses the full spectrum of human emotions and a lot of times, it’s a very swoony kind of melancholy.

HUXTABLE: Exactly.

TAYLOR: When I’m actually depressed, I’m not spending three hours putting on makeup and choosing an outfit and listening to music, I’m sitting on my couch not moving. There’s a performative melancholy that I kind of love about it.

UDEMEZUE: Juliana, what was the beginning of your attraction to goth and rock music when you were younger?

HUXTABLE: I’ve always been drawn towards the melancholic. I had a sense of double alienation growing up because I grew up in the south, super religious, and knew I was queer really early on. I was part of a vibrant Black community, but in the context of a very conservative, white, Bible belt population. I feel that there’s an indefinite mourning that is tied to so many Black diasporic communities. So the church was my first real encounter with a highly dramatized, almost manic fixation on rituals surrounding death, loss, and generations of disenfranchisement. That sensibility was always there, and I was always attracted to the little gleams I got of what’s considered goth culture early on. When I was coming up, it was kind of like dark wave EDM. I had emo and screamo, but really the most intense version of that was in the church. When I got to college, I remember taking a Romantic literature class and the majority of it ended up being about gothic literature. I love British post-punk music and I love that British sense of malaise, which your book really got me thinking about. The gothic sensibility can be an opportunity to process historical trauma, and for me, that was so much of the draw. Christian Death is my favorite band, and I absolutely love the way that Rozz processes the religious upbringing they had.

UDEMEZUE: I grew up with both Pocomania and Spiritual Baptist churches, and there’s still a lot of shame around those religions being tied to something that is quote, unquote “scary voodoo.” The obsession with death and ancestors in a non-negative way was a very real thing in my upbringing. But I did my research about Caribbean religions, and for example, there is no gender binary in Vodou. There’s tons of history about third genders coming out of Angola, and those third gender people were spiritual leaders and military leaders. The diaspora is way more queer than people want to put on, and that’s a separate conversation. But when it comes to the gothic, it’s kind of a death of self because I wasn’t feeling seen in either of these Americana or Caribbean spaces I was brought up in. It’s nice to now connect all those dots. Death is definitely something we’re always thinking about as Black people.

TAYLOR: Yeah.

HUXTABLE: And I think it’s not for nothing that so much goth culture in the States centered around Detroit or New Orleans. Detroit exemplifies the failures of the great migration and the steel boom and the American gilded promise of a new era. You go to much of the Midwest now and it’s just these ghost towns. My grandparents lived in Gary, Indiana.

TAYLOR: Yeah, the Rust belt.

HUXTABLE: Even German industrial bands will come play in the Midwest. It’s so funny. They’re not even going to San Francisco, but they’re moving through these areas.

TAYLOR: Yeah, I mean I’m pretty solidly Midwestern. My mom’s from Indiana, my dad’s from Kansas, I grew up in Ohio and Michigan. So the Midwest weirdness is there.

HUXTABLE: For sure.

TAYLOR: There’s a lot of denial and repression and so much space. I think one thing that’s particularly American gothic, as opposed to a claustrophobic dark castle, is the creepiness of having too much space around you. In Detroit, it’s really unique seeing pockets of buildings that have been left to rot in ways that you normally don’t see. Normally, we buy something and rehab it or tear it down and build something horrible anew, so having remnants of this American gilded age of industry just slowly decay is so intriguing and beautiful. On the other hand, there’s the cost of the real, tangible socio-economic problems that made this particularly gothic melancholy happen. But I love ruin porn, I’ll admit it.

UDEMEZUE: It’s funny you mentioned the ruin porn, because before I actually started to go to Jamaica, I thought it was going to be beaches and everything’s beautiful. The danger of being a queer person was obviously on my mind, but once I actually spent time on the island outside of resorts and my Airbnb, there’s a kind of beautiful and complicated ruin porn happening. Everything is in bold, beautiful, bright color, but there’s a complicated relationship to history and danger and all because of the abuse from the West, and we still see abuse and colonization happening to this day. Another part of this show that I really wanted to focus on is that the characters in the images are boys falling in love. There’s a video of this young femme Palestinian boy dancing that I posted on RAGGA, and I said that it’s a shame that the West is going to have to wait 10 years to really validate this person’s story. Queer people are there in Palestine. It’s the same thing they’ve said about Jamaica, because there are no official gay bars in Jamaica: “There are no queer people in these places and only a gay bar from Chelsea will save them.” And it’s like, that’s not true and you’re dropping a bomb culturally, financially, physically on them. I hope that with this work, people are reminded about that humanity. It shouldn’t have to be in the ruins when the flowers have grown over the dead that we think, “We should’ve seen their humanity from the jump.”

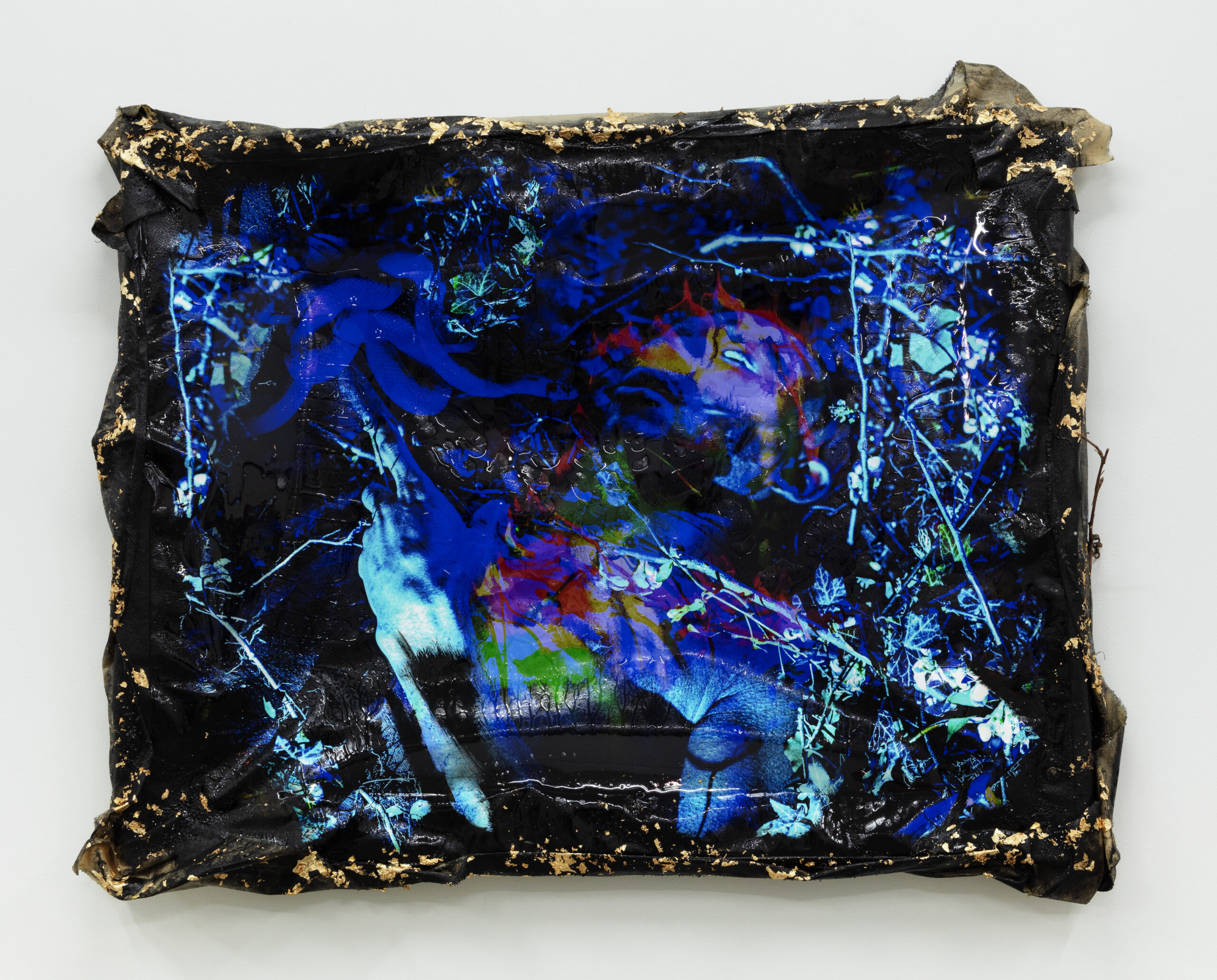

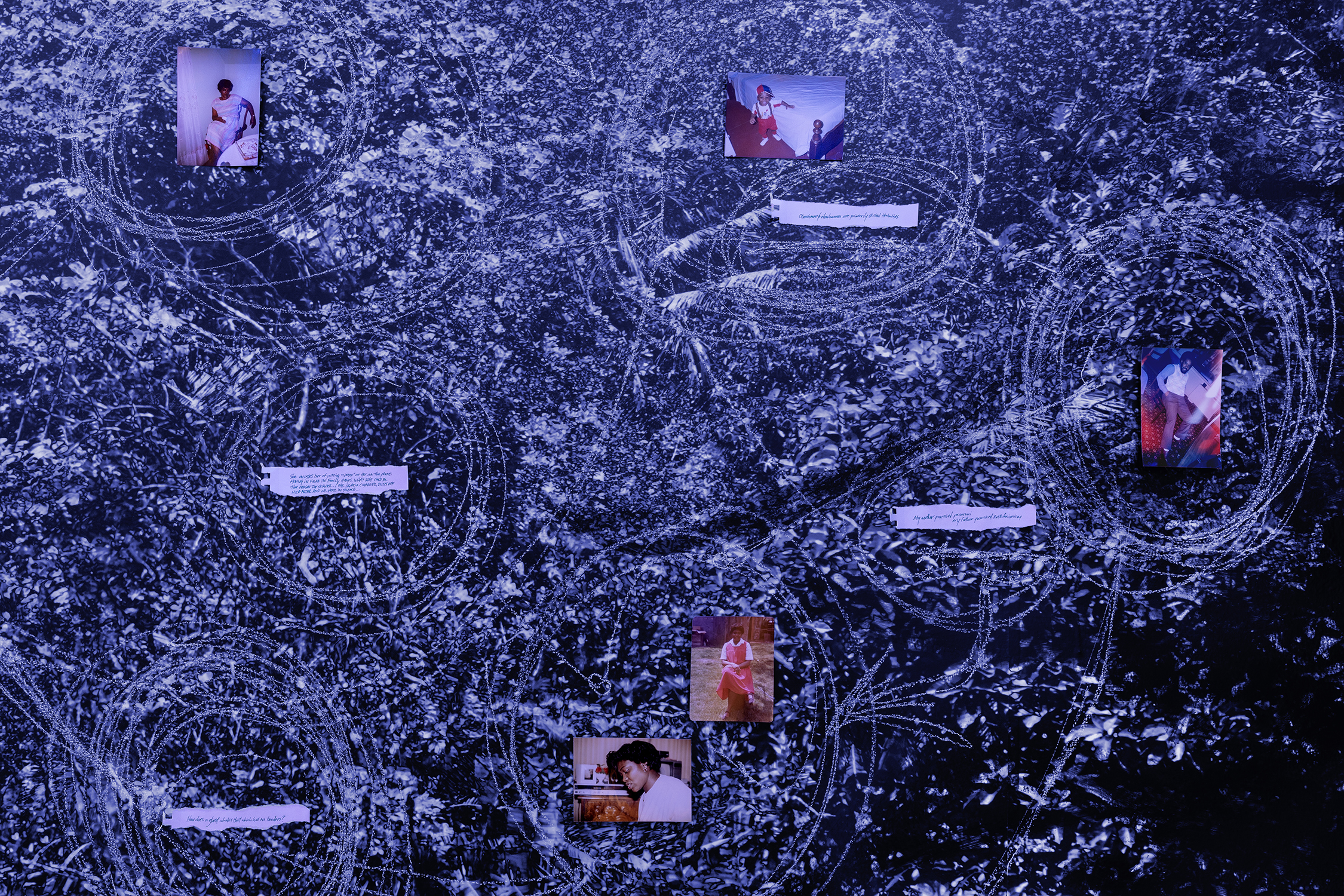

“in this moisture between us where the guinep peels lay” installation by Christopher Udemezue (2024).

TAYLOR: That leads me to a question I was going to ask about one of your works, which is the mural of the house.

UDEMEZUE: Yes.

TAYLOR: I’m working on something about how horror perverts our ideas of what home is. It’s called Sick Houses, Haunted Homes and the Architecture of Dread. As a genre, horror plays with our insecurities and desires about home, so I’m curious about your house.

UDEMEZUE: I made that piece a week ago. I didn’t know what I was doing, and everyone’s like, “This is the one.” That image is actually my family’s house in Jamaica. When I took the image, I stepped out of the van in Bickersteth, Jamaica—my family’s from the deep country—and when I saw the house on top of the hill, I just grabbed my camera and snapped it. I always say that the city is the city, but in the country, there’s no street signs and my family will be like, “You cross the mango bush and you go up the street where the coconut tree is,” and I’m like, “That’s not an address.” [Laughs] I was so welcomed by everyone there, but at the time there was so much melancholy in my heart because I had conversations with my mom about all the horrors they experienced on this land and the anxiousness of not having protection. My mom grew up during the aggressive times when Bob Marley was assassinated and the American government had their hands all up and through the Caribbean. They infused the island with a bunch of drugs and guns. So of course in the countryside where things are more lawless, per se, she experienced a lot of violence. And I’m sitting here looking at this beautiful pink little house in the country, but I’m thinking about how much pain was in this same place. There’s this little girl who lives down the block running around the house, and I’m thinking of my mom as this little girl. This was her haunted house, this little house in the middle of the country. So when it came time to make the installation, I thought about how this is a beautiful place, but a complicated, heavy place. It’s my family’s haunted house, ’cause no one’s gone back since me for 25 years.

TAYLOR: Oh, wow.

UDEMEZUE: Everyone was like, “Don’t go, don’t go.” I got there and my mom was like, “FaceTime me right now.” It was a thing. So I mind mapped that entire journey, from images of my father and my mother, my grandmother’s notes from my findings, and history about third genders and queer Orishas in the Caribbean, and put it into that installation. In my family, it’s this haunted place, but it’s so bright. That’s why I flipped it and colored the whole thing.

“in this moisture between us where the guinep peels lay” installation by Christopher Udemezue (2024).

TAYLOR: Didn’t you describe it as a horror and a love story?

UDEMEZUE: Yes. This show’s a horror love story.

TAYLOR: That is the gothic in a nutshell, for me. There is gorgeousness in the imagery, there’s otherworldliness, lusciousness, there’s a little Afrofuturism I’m picking up on. But at the same time, there’s an encompassing darkness around that.There’s something equally beautiful and a little bit scary in some of those images. I’m intrigued by them. My little screen isn’t enough, I got to get all up in there.

HUXTABLE: The show is amazing.

TAYLOR: How did the decision to bring in Richmond Barthé come about?

UDEMEZUE: The gallery actually hit me up. They were like, “We know that you do RAGGA NYC and you often talk about intergenerational conversations and giving props to other diaspora artists, would you be interested in a dual show with us?” And I was like, “Yes.” It makes sense because he actually was gay and not hiding. There’s obviously no records of him and his lover, but he was gay and he spent time in Jamaica. He actually left the States because as he got more successful, there were a lot of stresses of what success meant for him as a Black artist. So he spent 20 years living as a proud gay man in Jamaica during the Harlem Renaissance. It was a healing place for him.

TAYLOR: Is this the ‘40s to ’60s?

UDEMEZUE: Yeah. I felt like my trip healed me, but it’s beautiful to know that people have been doing this.

HUXTABLE: It’s really important to get into the history ’cause so much of post-punk comes directly from Jamaican immigrants to the UK. If you listen to The Slits, who aren’t considered goth, but they’re from that era of the UK, all of that music is like reggae, ska, dancehall. I remember when I sent you that Bauhaus song that was literally just a white man on top of an early dancehall or reggae track. So much Black diasporic expression is really served a short hand. I experienced this, especially because I love gospel music. So much of it is about building in a highly dramaturgical performative relationship to death, and building a sense of the culturally specific sublime from that. So often Black people are unfortunately forced into the indignity of being denied basic things like a cultural sensibility. It’s like, “Of course they’re sad because their lives are sad and they experience violence,” like there’s not an entire culture that’s attempting to weave these things into something that can be beautiful. So the work that both of you are doing is important so that sort of erasure doesn’t happen, as if the documentary or the journalistic is the only way that we can be understood.

TAYLOR: There’s a little theory that I keep working on called “the privilege of frivolity.” The ability to safely be authentically strange and bizarre is really important. Black people are killed in this country because they were acting “weird.”

HUXTABLE: Literally.

UDEMEZUE: Literally.

TAYLOR: So having this growing community to express individuality is really important. Both of your work feels uniquely personal.

UDEMEZUE: Thank you so much for saying that. So much of my previous work is about my relationship to trauma and violence, and I’ve used the trope of the white hand reaching to the figure a handful of times in my work. But even if the work isn’t centering that hand, it’s still about how it relates to these white folk. In this body of work, there are no white hands. What is my work outside of this relationship to slavery? What happens when they got to the Blue Mountains? They were just chilling and making out and dancing and experiencing joy and connecting to deities and Orishas and taking that weird mushroom they found. I told Juliana, one of the pieces is literally me and you dancing together this past summer. The container may be a horror film, but it’s very much a love story, and the allegory is romance and survival, ’cause we’re not talking about that plantation. They’re vibing, they’re in the Blue Mountains, they found a field of mushrooms, they’re falling in love.

TAYLOR: That’s what I love about Afrofuturism. What is it like to be Black in a world where colonialism doesn’t exist?

UDEMEZUE: Right.

TAYLOR: I was looking at the photographs of the little alien ears and I loved it ’cause it’s strange and I don’t know exactly what it means. I like how otherworldly it is. We need that kind of joy in expression. It’s kind of vital for survival, I think.