IN CONVERSATION

Christine Tien Wang and Kenny Schachter Get Real About Art World Economics

Christine Tien Wang, photographed by Arturo Sanchez. Images courtesy of the Artist and The Hole.

Christine Tien Wang and Kenny Schachter are in the business of self-abasement. The two multi-media artists, hailing from San Francisco and New York respectively, have a lot in common: they’re both fascinated, and frustrated, by the avaricious nature of the art world. In their work, they look to provoke by way of humor and humiliation. That they both have solo exhibitions opening at the same time, each exploring the cultural impacts of excessive technology use, is just the cherry on top. Exhibiting at The Hole in New York, Wang recreates, or “re-deploys,” as Schachter proposed, a series of popular memes that confront the bizarre and inherently comical nature of cryptocurrencies. “I wanted to lean into the fear and embarrassment of copying, and of using a dead medium like painting,” she explained of her show, CryptoFIRE Degen , when she and Schachter got together over Zoom earlier this month. His show, Phone Face, which opens today in Cologne and includes a number of paintings and sculptures accompanied by sardonic or “gossipy” texts, considers the screen as a projection of the “masks of detachment” that shape contemporary existence. After meeting briefly at a cocktail party in L.A. earlier this year, a more formal tête-à-tête was long overdue, so we convened the artists for a candid conversation about crypto, narcissism, humiliation, and the art world’s money problem.—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

CHRISTINE TIEN WANG: Hi, Kenny.

KENNY SCHACHTER: Hi. How are you?

WANG: Good, how are you?

SCHACHTER: So funny how we meet in the most bizarre places. One was a random cocktail party in Los Angeles. Where are you now?

WANG: I’m in San Francisco.

SCHACHTER: Ah, I’ve been once in my life. I went to visit Lynn Hershman Leeson.

WANG: Oh, yeah? She’s amazing.

SCHACHTER: She is a truly extraordinary and pioneering artist and person. And feminist.

WANG: Yes. Then in L.A. the day after, I went to see I Object [2024] with my sister, and we loved it.

SCHACHTER: You’re so very kind. Thank you.

WANG: And she’s not even an art person.

SCHACHTER: All the better. With regard to your upcoming show in New York and my show in Cologne, it was a coincidence that we share the same representation in Germany. Also, I don’t know if you exclusively depict memes, but my upcoming show is loosely based around the theme of the impact of social media on our lives, and how the history of the art world has been transformed over time.

WANG: Yeah, I’m excited for Phone Face. I’m in the middle of Claire Bishop’s book about attention, and she’s talking about social media a lot and how it’s changed our attention spans and the types of attention that we have.

Christine Tien Wang. Drinking Milk, 2024. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 60 x 60 in. Images Courtesy of The Artist and The Hole.

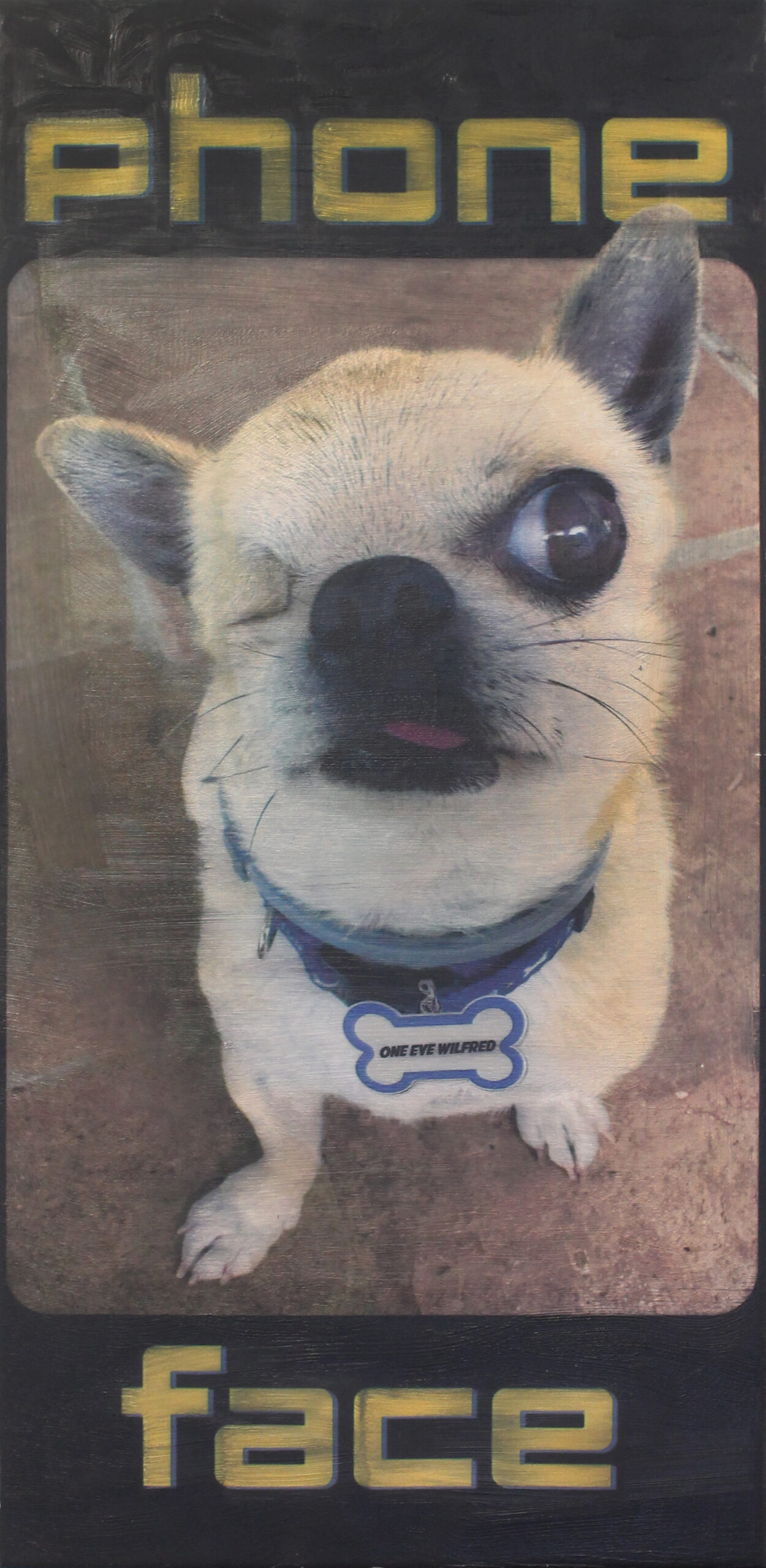

SCHACHTER: Interesting. I made this piece in 2018, the Selfie Man sculpture, and it has to do the way that attention spans: not only the attention span of people, but how the biological structure of children’s brains are being engineered by psychologists who are working as algorithmic engineers in the space of technology companies. It’s a little bit frightening. Also, the title of my show comes from this term “Photo Face,” which was referring to one of my favorite photographers, Peter Hujar. Somebody referred to his photography as more ad hoc and not photo face, where people are posing for the camera. Now, everyone’s posing for their telephone. What’s the name of your upcoming show?

WANG: It’s going to be CryptoFIRE Degen.

SCHACHTER: Amazing. Also, the way you paint memes, I don’t know if that’s how you refer to them, or–

WANG: Yeah.

SCHACHTER: It’s almost like the choice of white by Robert Ryman, in a funny way.

WANG: Oh, wow. What a compliment.

SCHACHTER: It’s a formal constant. Like, he chose white, but within the rubric of this pigment he painted different variations that were never the same; whether it was width, or the texture of the brushstroke, or the underpainting. There were so many variables within this tight parameter. In a way, your paintings are wildly different in what they represent. Another thing that we also very much have in common is employing language in our artworks and our self-expression.

WANG: Well, thanks so much for that compliment. It’s so flattering, but I also think it speaks to the attention issue. People are always like, “Why do you paint memes?” I think part of it is the attention issue, because painting is so slow and social media is so fast. My brain’s too slow for social media. I don’t think I can keep up.

SCHACHTER: I’m not saying it particularly indicates any level of intelligence, but my brain is like an atom smasher. I always have a million different things colliding in my head. Are your memes straight off the internet? Is there any authorship in your usage of language in your paintings?

WANG: I do make a couple of the memes, but I steal most of them.

SCHACHTER: I didn’t say you steal. I would say you–

WANG: Appropriate?

SCHACHTER: Appropriate or re-deploy, let’s put it that way.

WANG: Re-deploy, thanks. I also love that you use language in your work, and I love reading all of the articles. I feel like, for me, writing is the text in my art. It’s all in contrast to the subtext, maybe.

SCHACHTER: Right, because I thought there’s a particular connection between the message of the text that relates to the picture.

Kenny Schachter. The Richard Joke, 2024. Manufactory Painting Oil on canvas. 24 x 39 inch. Courtesy: Kenny Schachter and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne/Munich.

WANG: Yeah, for sure. What struck me about the language that you like to use is this: I identify with the lack of embarrassment, the gossipy tone of voice, and then the financial transparency. I’m like, “Yes, I live for it.”

SCHACHTER: I’m constantly embarrassing and humiliating myself in front of my children.

WANG: To me, it’s like when Philip Guston switched to those cartoony paintings and nobody liked them, but they were all about freedom.

SCHACHTER: You’re just making the hair stand up on my arm. I related you to Robert Ryman. He was personally ostracized by his friends and his community of peers. I don’t have loads of friends, or many for that matter, but I don’t really like the gossip word. Sometimes I engage in this revelatory way, but I just think in order to communicate with people. I recently read a statement that Cory Arcangel made. He did this extraordinary project with the estate of Michel Majerus, where they spent seven years painstakingly rescuing this hard drive that survived the plane crash that tragically and prematurely took his life. He was saying that whether it’s entertainment, or art, or any of these ways we engage—poetry, fiction, non-fiction—it’s all about how difficult it is. Whether it’s Instagram, Facebook, or in a gallery or a museum, it’s about getting people to stand in front of it and consider what you’re doing. I think that we both use technology conceptually and metaphorically. Technology is not just a tool; it’s a way of life and an extension of our minds and our limbs and our eyes, everything.

WANG: Yeah. Technology and culture are the same in some ways.

SCHACHTER: Tell me your conception of freedom in relationship to what you do. I hate saying the word practice, so I’m going to avoid it.

WANG: Well, my goal is to embarrass myself.

SCHACHTER: I think failure is important.

WANG: Yeah. I want to lean into the fear and embarrassment of copying and of using a dead medium like painting. Well, not dead, but it’s certainly a very crude technology compared to a computer.

SCHACHTER: I never thought of it in those terms. My son, Adrian, uses AI to reinterpret historical imagery, and then he paints in the most traditional way, like you.

WANG: What do your children think about technology and social media? I heard that there’s a Gen Z backlash, and some people want dumb phones, but maybe that’s just the Washington Post being hysterical.

SCHACHTER: I think the kids pay lip service to that. But I’ve been told in no uncertain terms by my children and my gallery, for that matter, about my oversharing. I’ve since scaled back as I get more focused, and I’ve just been so busy making work. I have to use my fingers because I’m not terribly numerically oriented. But, yeah, humor; your work is fucking funny.

WANG: So is yours. I love it.

Christine Tien Wang. Awkward Look Meme, 2024. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 72×72 in.

SCHACHTER: I think humor is a disarming and wonderful way to speak to people and engage. It’s such a great defense mechanism. Being funny diminishes sadness and pain.

WANG: You’re right. Humor is necessary because you’re saying some really uncomfortable truths about the art market or art world, which is that wealth inequality has really permeated the fair scene or stuff like that. For me, if I don’t laugh at it, I’m going to cry.

SCHACHTER: What I get so pissed off about is that the art world has its own brand of hypocrisy, and there’s a hierarchy that really annoys me.

WANG: Okay. I want your advice, Kenny.

SCHACHTER: But let me ask this quick question first. What dictates the size of your paintings?

WANG: The bigger, the better.

SCHACHTER: You sound like Julian Schnabel.

WANG: I like his work, too.

SCHACHTER: I do too, but he’s never seen a scale that was too big for him. Too big is an office building size. Size does matter, I guess.

WANG: My canvases are not as big as Julian’s. But can I get your advice?

SCHACHTER: Fire away.

WANG: Every year, I do this oversharing thing with my students around tax time. I tell everyone my “Schedule C,” which is how much I spend on my art, and so on and so forth.

SCHACHTER: That’s epic. I love that.

WANG: Then I say, “Here’s the paintings that I made last year, and this is how much each one sold for, and this is how much I got.” Of course, this is all very private information, but my students like it because, like you, they hate the hypocrisy in the art world where everything, especially around money, is so secret. I got a comment on Instagram saying that I should make these Schedule C lectures into a book. But that seems really scary to me, and it’s easier to talk about it live because people can just forget it or there’s no record. Do I turn it into a book? Should I be more public? It’s really scary.

SCHACHTER: First of all, there’s a piece that you must look at soon as we get off the phone. It’s by the artist RH Quaytman.

WANG: Oh, yeah.

SCHACHTER: She ran a small emerging art gallery, either in the ’90s or in the early 2000s. She made a giant print which had every work of art that she sold, identifying the price and the buyer of every piece.

WANG: Oh, wow.

Kenny Schachter. Data, 2024 from the series Phone Face, 2024. Sculpture. Cast aluminium, painted 60 x 60 x 51 cm. Courtesy: Kenny Schachter and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne/Munich.

SCHACHTER: She breached this kind of unspoken [rule]. The art world is almost like the mafia’s omertà. It’s why I caused so much havoc in my writing. I’ve had lawsuits threatened, people trying to literally beat me up in restaurants. Once, Wolfgang Tillmans was DJing at a party that Sam Keller threw in conjunction with Art Basel in Hong Kong and someone threw a punch at me, and one of my kids dove in front and deflected the fist. I always say art and money–excuse my language–they’ve always fucked, but they should be sleeping in separate beds. What people don’t understand is that the history of artists embracing money goes back to Leonardo da Vinci. If he had one commission and a better one came along, he would renege on a contract. Even Mark Rothko, he took a commission to make these giant paintings for the Four Seasons and then he changed his mind. No one shares the basic information of how the art world functions, what the commissions are. Artists are the first ones to get screwed in every transaction that goes awry, because there’s such a lack of transparency and communication. But you’re a successful artist, and your work gets seen and embraced. I think a lot of people would be very curious. If you could sleep at night, and not be fearful, and not be embarrassed, then by all means, do it. I would be humiliated to go that far. Even me.

WANG: Well, you’re my hero.

SCHACHTER: It would be so embarrassing. But if you’re willing to do that, hats off to you.

WANG: I’m so happy we got to talk.

SCHACHTER: I know. I can’t wait to see your show. Oh, what do you think about AI? Have you ever used it in your paintings?

WANG: My husband’s in tech and he says, “AI is whatever technology we don’t have yet.”

SCHACHTER: I don’t understand what he means.

WANG: Right now, my phone can tell me a map route. Before that happened, maybe we would’ve thought of it as AI. Maybe 20 years ago, the idea of the phone directing me would’ve been like, “Wow, that’s AI.” Now that I have it, I’m like, “Oh, that’s not AI. That’s just a tool.” I think we are pretty far from a general AI that knows everything. Right now, the neural nets are trained to give us a language model. Then there’s also image generators; they’re fine. I’m hoping that the AI will make some nice memes so that I can paint them.

SCHACHTER: Have you ever tried to generate memes?

Christine Tien Wang. Mean Girls Crypto, 2024. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 60 x 6o in. Images Courtesy of The Artist and The Hole.

WANG: From AI? There are some floating around, and there are some that are made by people, but none of them are funny enough for me yet.

SCHACHTER: I’m really excited about this aspect of my show that I forgot to mention. I’ve been able to foster and facilitate this degree of collaboration and cooperation between Nagel Draxler and MakersPlace, where every physical sculpture and painting will have a digital counterpart, which will be a short form video animation. MakersPlace will present them as a bundle of a physical and an NFT.

WANG: I like that. Do you know if MakersPlace is using Ethereum or Solana or…?

SCHACHTER: They use Ethereum. Have you ever made an NFT?

WANG: I did. Some people use NFTs as certificates of authenticity.

SCHACHTER: I have a drawer full of paper certificates of authenticity from various artworks I’ve owned for like, 35 years. You mentioned that your paintings are biographical. That’s a really interesting way to tell a personal story from something that seems absolutely impersonal.

WANG: Yeah. Well, it just goes to show how badly I want to overshare. But then my version of oversharing is these very cold photos, like tri-quasi photorealistic memes.

SCHACHTER: The humor could be seen as…

WANG: Self-deprecating?

SCHACHTER: No, as misogynistic or mean spirited or overtly sexual in a derogatory way. Can you shoot me some of the subject matter of the pieces you’ll be exhibiting?

WANG: There are women. I find it really fascinating that the bodies of women can just hold all of these projections from the collective unconscious. By painting these memes, I want to point out that type of blankness that culture assigns to images of women.

SCHACHTER: It’s funny, because female nudity probably far supersedes the amount of male nudes throughout the history of art.

WANG: Of course.

SCHACHTER: I’m averse to female nudity in contemporary art, unless it’s coming from someone like you, with a point to make.

Kenny Schachter. Dog‘s life 1, 2024. Manufactory Painting Oil on canvas. 20 x 40 inches. Courtesy: Kenny Schachter and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne/Munich.

WANG: Well, I think if memes are my white paint or whatever, the bodies of women become the white paint of society in general. It’s like, “Oh, we can do whatever we want with these pictures.”

SCHACHTER: That’s really fascinating.

WANG: I don’t know.

SCHACHTER: You do know, and it’s great. I never really even thought of something so stupid, because I’m stupid. But “me me” spells meme.

WANG: My mother-in-law says mem. Then my mom, who’s Chinese, says mei-mei.

SCHACHTER: I just think it spells out me: me, me, me, me, me. Which is ultimately what they’re all about.

WANG: Yay, narcissistic artists. Woo-hoo!

SCHACHTER: My kid called me a narcissist with low self-esteem, which I thought should be on my tombstone.

WANG: I think that’s all of us.

SCHACHTER: Yeah, I guess.