IN STUDIO

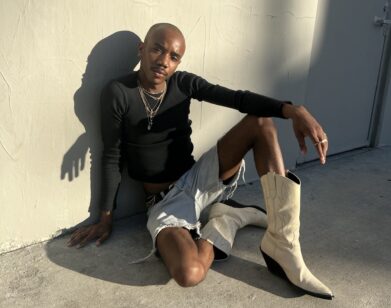

Chella Man Is Collaborating With His Younger Selves

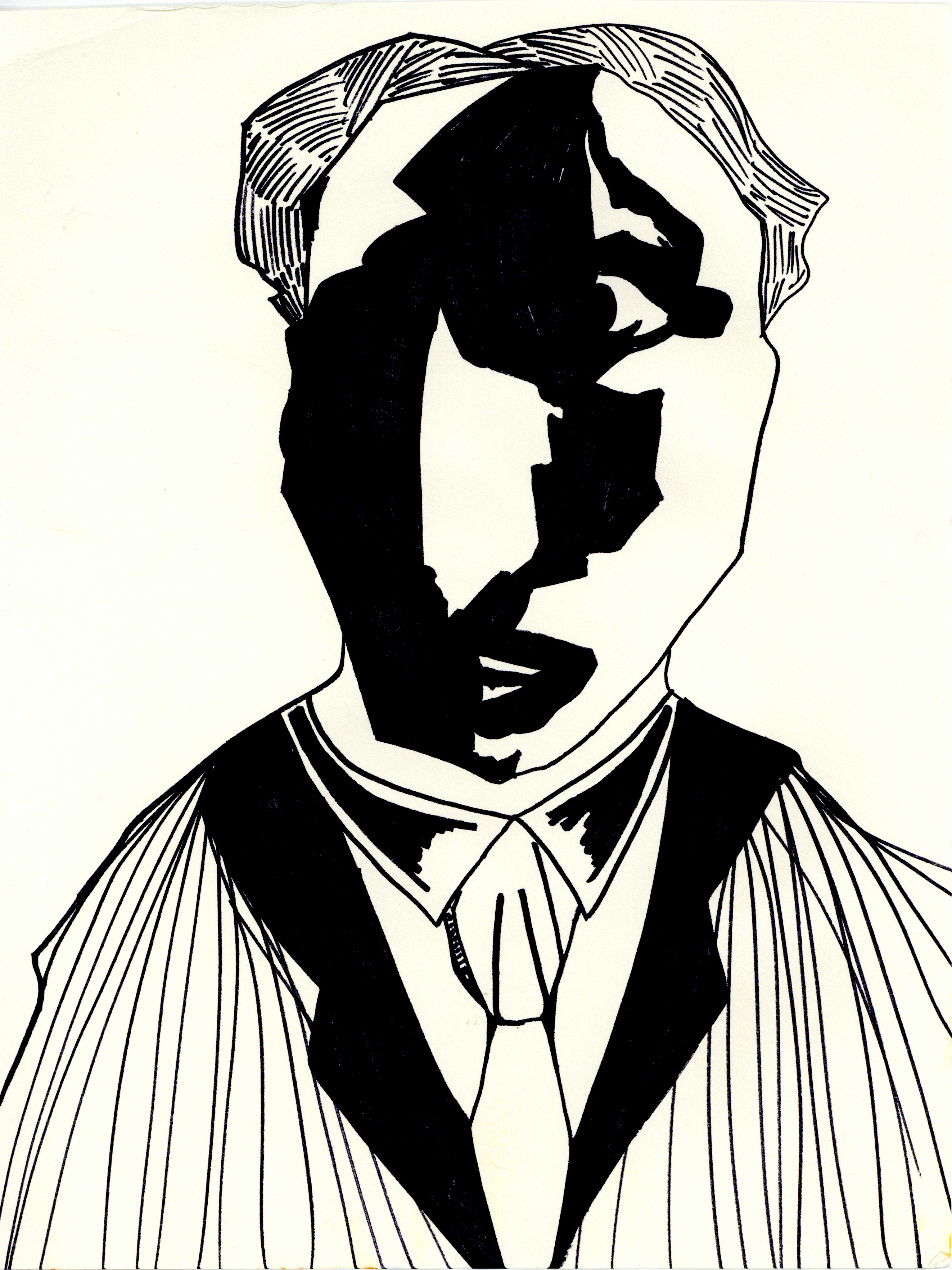

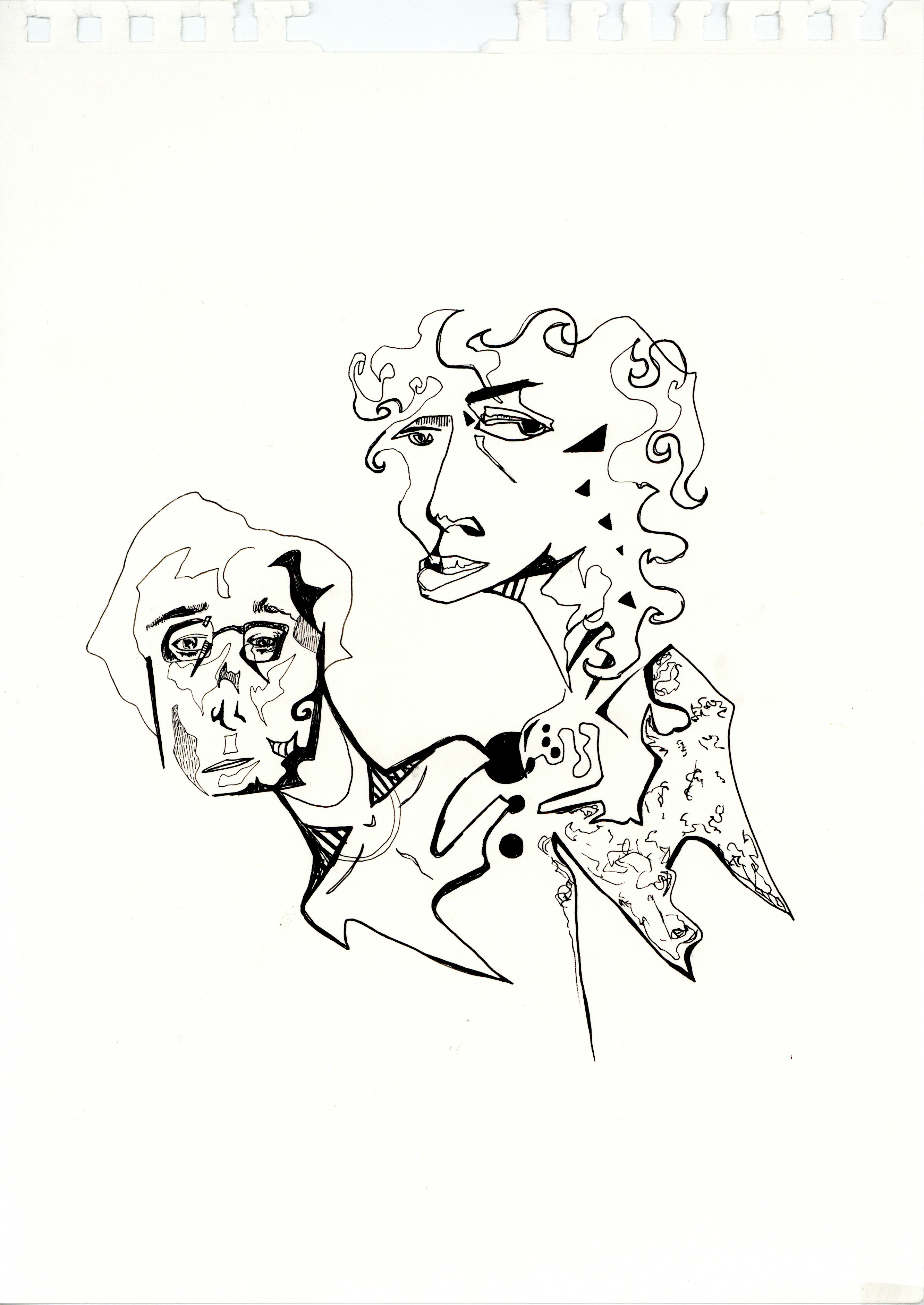

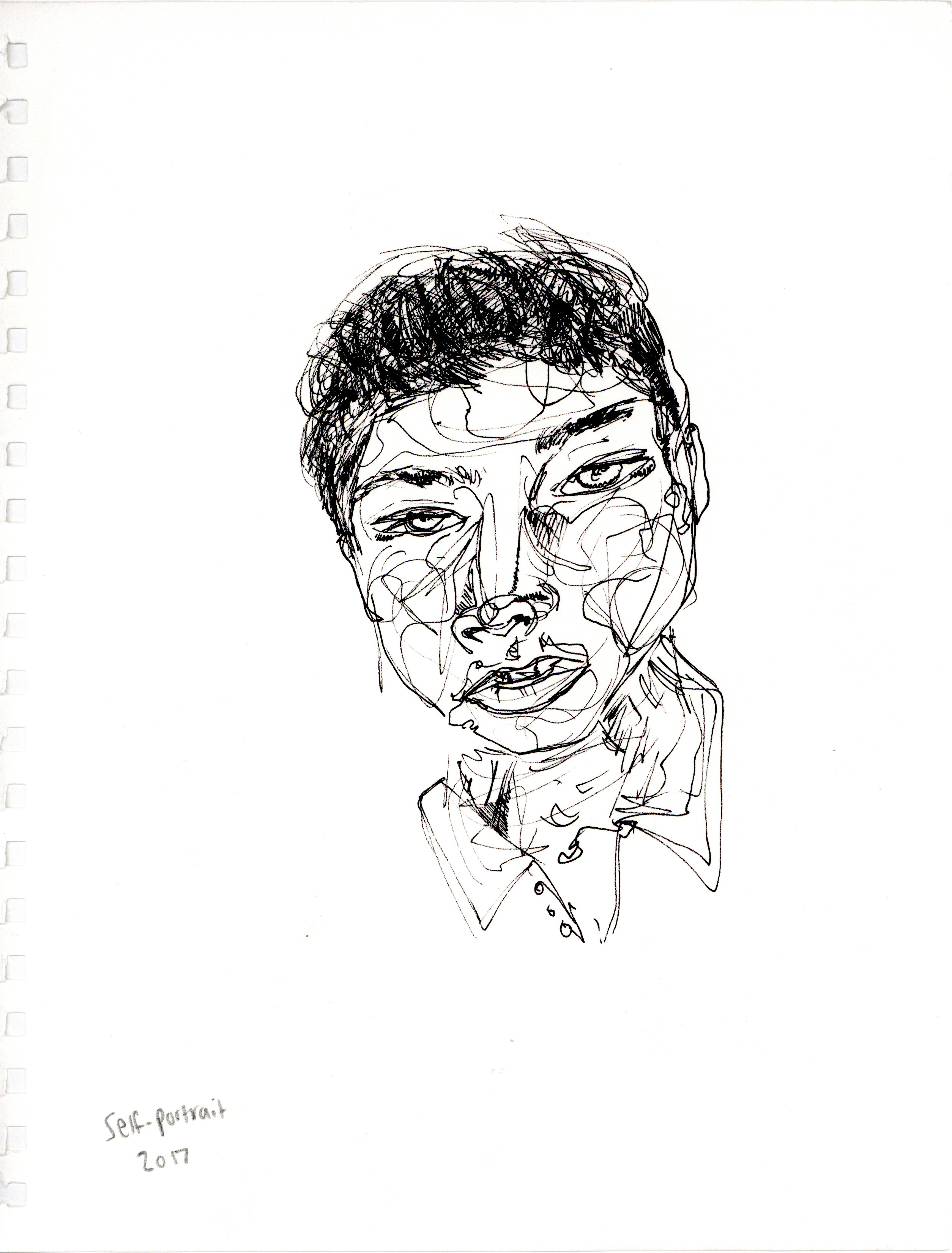

Earlier this month, It Doesn’t Have To Make Sense, a new exhibition by the artist and activist Chella Man, opened at Hannah Traore Gallery. The show is in some ways a retrospective, not just of Man’s sketches and paintings from 2014 to the present, but of the artist’s and author’s lineage, an homage to the inherited, structured forms that dictated his past, which Man, in turn, has redefined through his free, wandering lines that move without seeking any binary system, any beginning or end. “I’m collaborating with my younger self,” the artist says. “I’m able to provide the words that I didn’t have at that age.”

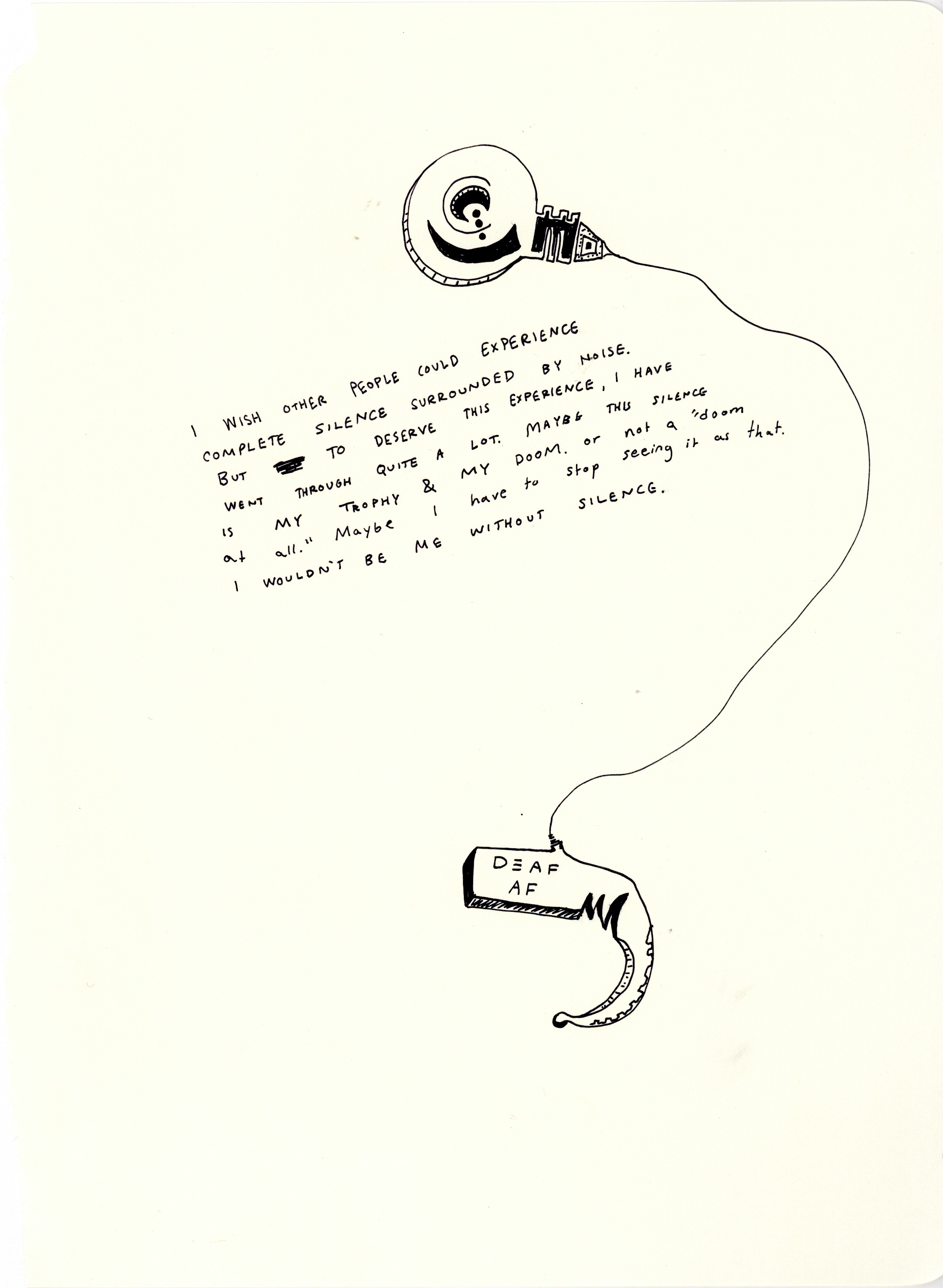

For Man, as a Deaf, trans, Chinese, and Jewish artist, language has never granted him true fulfillment. Man’s work instead seeks to embody his multiplicity of identities, gesturing toward his grandfather’s practice of Chinese calligraphy. “He’s somebody who had to live in a generation that had a lot of rules and a lot of structure,” says Man. Most recently, by learning alongside his grandfather, Man has arrived at a place of abundant gratitude. “I feel very grateful for my grandpa, for his lines. He gave me the ability to make my lines different.” After the show’s opening, Man got on Zoom with fellow artist, Christine Sun Kim, whose work also explores Deaf culture. Together with ASL interpreter Beth Staehle, the two unpack the process of collaborating with their younger selves, embracing abundance, and trusting their audience to just get it.

———

CHRISTINE SUN KIM: So, where are you now?

CHELLA MAN: Well, now I am here in L.A. and it’s really nice, because I feel like I needed a little bit of an energy shift from New York. Feng Shui is happening for me here.

KIM: How’s the weather? Because I miss L.A. I love California.

MAN: It feels like, I don’t know, a new year to be honest. I can feel the sunshine in New York when I’m there, but it doesn’t seep through my skin. When the sun hits me here, though, I feel it in my bones, and I really do appreciate that.

KIM: In California, that question hits different, because when you’re asking how the weather is, we really mean it.

MAN: I agree.

KIM: Tell me about the show that you had in New York. I saw some photos. I saw that you have your pieces framed. I also saw one piece that was from 2015, and the hand-drawing style that you had looks so much different than what you do now. Even your handwriting has changed. Talk me through that.

MAN: You know what? It’s really tough, because I’ve got a stack of thousands of sketches that I’ve had through my time, and I had to go through them every day. I had to go through them and just feel everything that I had felt back at that time. Honestly, I’ve had some photos before from the past, but for whatever reason, the sketches hit differently. I feel like I can more easily connect with my mind at that time when I see those sketches. When I reflect on my sketches, I know what was happening inside my brain. It feels like a much more emotional process. So I needed to really make sure that I had the capacity for all the emotions that I knew I was going to feel reflecting on all these pieces. And it was really helpful to have the perspective of the gallery owner, Hannah [Traore]. It made the whole process a lot easier because she was detached from the pieces, and because of that, was able to make more strategic choices.

KIM: Maybe you can talk to me a little bit more about how you look at those different pages through all those years. Are you seeing yourself as a little child growing up? Because I just recently had EMDR therapy and I really struggled to accept my young self. It always reminds me of a time in my life when I was struggling with transitions, kind of awkward growing up, and I always cringe to look at my old work. Even to this day, I struggle to engage with it.

MAN: It’s really interesting that you share about EMDR, because I was doing IFS. Have you heard of it?

KIM: No, I haven’t. What does that mean?

MAN: It means Internal Family Systems. That’s basically where you have a conversation with your younger self.

KIM: Wow.

MAN: Right. It’s heavy, but also beautiful. So doing that at the same time, every sketch, basically, felt like a portrayal that I could more easily access myself through, so it helped me remember so much about my life and about my own thoughts that I had forgotten up until this point. I actually forgot your question. I think I may have gone off on a tangent.

KIM: No, I was so engaged with your answer. What did I ask? I think I was just wanting to know more about your experience of looking at yourself through time.

MAN: So, I think it definitely enabled me to have a lot more empathy. Because with my perspective and my healing that I’ve done since that time, I’m just able to understand where and why that isolation that I felt then exists. I just had so much more compassion for how lonely I felt at that time. Art felt like a release for me. And now I can better understand and fully describe why I felt like it was a release at the time, which is really interesting because it almost feels like I’m collaborating with my younger self. I’m able to provide the words that I didn’t have at that age. All I had then was lines, visual images in my head, but no words to match it.

KIM: You’re right, art has forced me to develop more empathy for myself. And I did apologize to my inner child for holding so much of what I have over the years. Now, as an adult, I’ve let go of those things and I can share it with my inner child.

MAN: When you look back on your old work, do you remember the feelings that you had when you were creating that work?

KIM: They’re not good feelings. I think it took me a long time to really enjoy art-making, to be honest. I just recently got to a point where I really do enjoy it. It’s strange, I feel like it could have stopped me from making work but I just kept doing it because I had this inner urgency to create.

MAN: You had maybe a scarcity mindset?

KIM: Yeah, I just felt like I had to keep going. I didn’t realize that you were affected by your grandpa’s calligraphy. I’m really intrigued about that.

MAN: I only recently realized how I’ve been influenced by that. One of my grandpa’s biggest talents, when he was growing up, was doing calligraphy. And in recent years, I’ve been hanging out a lot more with my grandparents just because I want to cherish the time that I have with them. So I asked them to show me his calligraphy and some of his writing because that’s part of why my grandmother fell in love with him in the first place, so I feel like it’s an important part of my family’s history to look into. And when I watched him create the strokes that he makes, I saw that every stroke felt so bold and confident and deep. I was a little shocked, because I don’t really view my grandfather as an artist. To me, he’s always been somebody who’s more like an engineer type of person. And seeing him do that, I realized that, while I’ve always thought of my family as being very academic, this was the first time that I noticed myself and my artistic abilities in a family member of mine. And it just made me more curious about how that got passed down, that artistic trait. The thick black lines that he uses are similar to my work. He creates it very quickly and confidently and strongly.

KIM: Have you two done calligraphy together?

MAN: We have, yeah. He was actually teaching me all the ways and techniques. He was saying, “You work from top to bottom, you work left to right,” and that’s what’s different. He has a lot more structure in the calligraphy work, there’s a lot more rules. Whereas in my art, there are no rules. I’m very abstract.

KIM: Yes, very free-lined.

MAN: I feel like that’s also a comparison between our generations. He’s somebody who had to live in a generation that had a lot of rules and a lot of structure and that’s how his life was lived. And for me, I feel fortunate that all of the work that he’s done has given me the privilege of choosing to not live with so many rules and to not live in so much structure, so I feel very grateful for my grandpa, for his lines. He gave me the ability to make my lines different.

KIM: Yeah. It’s almost like you were saying, it’s a line passed down through the lines, and maybe through the generations. Another topic I wanted to talk about with you is safety.

MAN: Like, how do I define it?

KIM: Well, there’s two ways to go about it. I feel like you need to over-explain something sometimes to gain some kind of sense of security and safe space, but I also know that people like us don’t really owe anyone any explanation. Yet we do have to explain ourselves in order to get safety.

MAN: It’s funny. I agree with what you said about explaining. When I feel the most safe is when I don’t have to explain anything at all, when I find myself immersed in a space where people just get me and it’s almost unspoken. So much of my energy is oftentimes used for explaining my existence, explaining my access needs, explaining what makes me feel safe, when I can use that energy, instead, for other things. For enjoyment, for living, or having a conversation about something other than fighting for my existence. And when I create my art, I might not be immersed in spaces that are safe, but that paper becomes a blank slate for me that always gives me the autonomy to create whatever I want. It’s just for me. Art is so special in that way.

KIM: I do agree, but I don’t entirely agree about art being that space. For me, I feel like almost all the starting points, as an artist, finds you needing to explain. Unless you’ve got, I don’t know, some crazy big privilege, then yeah, you don’t have to explain. In the art world, I feel like it’s full of artists who have huge privileges. They come from generational wealth, they maybe come from famous artist parents, so they have that kind of lineage. I’ve noticed that that has given them the privilege to explain themselves less.

MAN: Yeah, but I think when you have to be in an industry and make money from your art, that’s when you do have to start explaining yourself. When I was just drawing at my desk and I’m not really thinking about showing it to anyone else, I’m creating for myself. I was never thinking about having to explain it to anyone. But when you get older and you want an audience, or maybe you also want to be involved in the business side of the industry, then yeah, I agree you do have to explain more.

KIM: The audience, most of the time, is smart enough that they get it. I explain less now, but it also helps that I have a really great team.

MAN: Right, I delegate.

KIM: And that comes from trust, too.

MAN: That’s true.

KIM: How would you like to close it, Chella?

MAN: I’m in L.A, right now working on a script for my next performance that I’ll be doing with the Jewish Museum and Performance Space New York. It’s really wild. So I have to recreate casting for my entire nude body and I’m planning to tattoo and talk about the tattoos. I’ll also be talking about my relationship with the medical industry, or industrial complex, rather, and my relationship with my family. They’re going to be a part of that show, so I really cherish this. If you’re in New York on May 2nd, you should come see it.

KIM: What can’t you do? It’s amazing.

MAN: There’s no limits!

This conversation was interpreted from ASL to English by Beth Staehle.