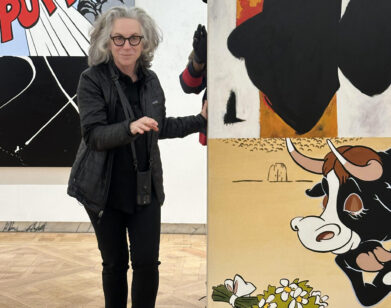

Cassie GRIFFIN

When Cassie Griffin greets me at the front door to her art studio inside Treasure Island Storage, a big red, white, and, blue depository in Red Hook, Brooklyn, she looks visibly relieved. “I was worried, but you look nice,” she says. Despite the surge of interest in her work lately, the young ceramist is still getting used to talking about herself. “I just turned 30,” she says. “I’m actually feeling very solid about it. I think that being okay with 30 has a lot to do with clay.”

Originally from a “kooky artist family” in the Poconos, Griffin moved to New York ten years ago with no planned trajectory in mind. After various waitressing jobs and a brief leave of absence to work on a dairy farm in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, she returned to the city and started cooking at Williamsburg’s Diner. “It was kind of dark days,” she recalls. “I would go in at six in the morning and leave at seven at night, and I wouldn’t see the light. I got really burnt out.” So, in 2010, when Griffin ran into a friend who was on her way to a pottery class, she decided to sign up. By the end of a year studying one-on-one with New York ceramist Helaine Sorgen, Griffin got her own studio and started making her own brand of minimalist pottery: geometric vases and playful, hand-painted pitchers, thrown on a wheel and often treated in bright, unorthodox glazes. “I purposefully never made really functional things because I knew that’s not what I wanted,” she says. “But I also knew that you can’t skip to the end. You have to work through the foundation.” These smaller, “foundational” pieces are what line the shelves at Dimes, a hip Chinatown restaurant run by her two friends, where Griffin occasionally works.

But right now it’s still the studio that houses her most ambitious and radical creations: two-foot-tall asymmetrical vessels with collapsing angles and rough glazes, the kinds of abstract pieces she’s planning to exhibit at her first solo show at New York’s Patrick Parrish gallery this month. Clearly, Griffin is pushing herself. “Sometimes I become really attached to the form, and it’s like, ‘This is so beautiful and elegant, and a really functional and easy-to-process piece,’ ” she says. “It takes me a little bit to let it go, and then I just keep going.”