How blind artist Manuel Solano learned to paint again

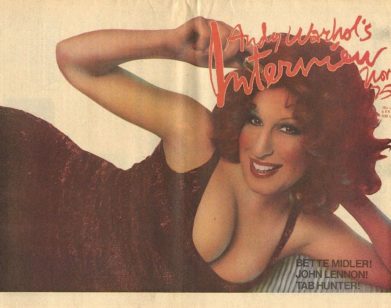

In Manuel Solano’s “The Basement”—the artist’s first grayscale painting since going blind—a somber figure stands alone in a corner, back turned, full of frustration. In “I’m Flying,” a quirky, vibrant nod to ’90s goth flick The Craft, Fairuza Balk lies strapped to a bed. These seem to represent the two sides of Solano, both silent struggle and feisty spirit.

Born in Ciudad Satélite, a suburb near Mexico City, to an engineer father and a business owner mother, Solano credits their parents for fostering their creativity and allowing them a freedom of self-expression not always available to children. Young Solano took to coloring books, dancing, and making plasticine figures. Things took a turn in early adulthood when, as the burgeoning artist was about to begin art school, they were hit with an HIV-related illness. Left untreated because they were repeatedly denied care by government clinics, Solano lost their sight in the spring of 2014, at 26 years old.

“I thought it was over,” they recall. “I thought I couldn’t be an artist if I was blind, for many reasons. I thought even if I tried to be an artist it would be seen as a joke, like a dog walking on its hind legs or something.”

But a friend convinced them to paint again, as an “experiment.” Solano hasn’t stopped since. Their first museum show, at the Museo de Arte Carillo Gil, took place two years later. Now, two years after that, Solano’s paintings will be exhibited at the fourth New Museum Triennial, along with the work of 25 other promising young artists from all over the world. In “Songs for Sabotage,” Solano considers the heightened role of identity in today’s world and wrestles with the fluidity of gender perception—specifically, their own.

Don’t be fooled, though: none of this came easily for Solano. The multidisciplinary artist reminds themselves everyday to keep moving forward, despite the obvious challenges that come with not being able to see their own artwork. Solano now employs tactile and oratory perception in order to complete a piece: outlining the canvas in physical markers, using their hands to apply paint, and asking friends for feedback.

JANE GAYDUK: How did the loss of your sight change the kind of artwork that you were creating?

MANUEL SOLANO: I had to start from the beginning again. I can never paint the way I was painting before I became blind, and so I had to reinvent my practice entirely. Back, before I became blind I was, I would say I usually painted oil on canvas, so when I became blind I had to change to acrylic on paper. And I had to start painting with my hands which I hadn’t done. And I had to start not questioning myself so much and not ever questioning whether or not I should paint something, because it would be valid as a work of art or as part of my work, but always ask myself why I want to make that painting. And to trust myself. I thought I needed to be very strong about what I say about it and what I put in there and—I’m saying it like that now but it wasn’t really a conscious decision—I just knew that I needed to be very behind my work. And looking back on it I know that, of course, it was obvious to me because it’s always been about the same thing, it’s always been about me.

GAYDUK: And tell me about the work that you’re doing for the New Museum. Are you experimenting with any different mediums?

SOLANO: No, I did experiment a lot for this body of work actually, but not with the medium. I worked on acrylic on canvas, and I worked on what I would call large format. These canvases are all larger than me, like 260 centimeters on their longest side. And I used acrylics, and I’m working with an assistant to make the colors for me and help me lay out tactile markers. I use tactile markers like pins and thread and pipe cleaners and stuff like that to mark different points on the composition. Then I feel my way around, put my hand to my paint, let my hand work.

GAYDUK: That’s incredible.

SOLANO: Yeah, and I was working like that by myself before these five paintings, but because it was such a time crunch I panicked, and I’ve been working with my ex-boyfriend of all people. He was the only person who understood that this was a kind of emergency and that I really needed to make my best paintings for the show. It was such a blessing to be working with him, to work with someone who knows me so well and who understands my sense of humor and, yeah, who loved me so much. It requires a lot of patience and a lot of knowing what I’m asking. Being blind, I find, requires a lot of asking, but especially requires knowing how to ask and what to ask.

GAYDUK: And in this particular show, “Songs for Sabotage,” what systems are you confronting and what kind of interventions are you exploring with your work?

SOLANO: In my work I’m in a place where I’m challenging my perception of my own gender and of my own role in society. I see the fluidity of my own gender perception and also my own identity, how my personality shifts. I find myself a very chameleonic individual and I am always taking from here and there and mixing it up into something else. And borrowing from pop culture, for example, but always to talk about myself and for these five paintings I’ve transgressed some personal barriers in terms of the subject matter for my work and some technical challenges, also. I painted a portrait of someone wearing pearls and I was afraid to paint that because the lighting on the pearls was very important for me to get right. Back when I was sighted, I was very proud of my ability to paint those types of effects accurately. The same painting made me realize some things about my own gender, through my work, and gender performativity and how much of our gender is the things we do to feel like we match our body and our mind.

GAYDUK: When you say “the things we do,” do you mean in a primarily superficial sense, like how we dress, if we wear makeup or if we don’t wear makeup?

SOLANO: Yes, the answer is yes, but what I’m trying to say is those things are not superficial. I mean, we see them as superficial because they are changes on our surface. But they definitely are symbols, right? And the human mind works through symbols. Our whole reality is constructed by our interpretation of symbols and signs, so these things do signify things in us and about ourselves. And I realize that I have been doing that, I have been making all this work using signs for things about myself, things that are here and are true. And coming to that realization after that painting was very emotional for me. So, I’m in a very strange place after that, for the past month.

GAYDUK: What do you mean by strange place, if you don’t mind me asking?

SOLANO: I can say I’m very confused about my identity and about my gender and that confusion began right before I became sick. So I really didn’t have time to think about it or even address it for years and only now, my work who is forcing me to address that. Through performance art, which I did, I spent some time in Portland last fall for TBA, Time Based Art Festival. I performed there and that triggered a lot of introspection, a lot of self-analysis. And I realized that I had been trying to show something, trying to express something through performance that I hadn’t been able to express yet. That I haven’t been able to express through painting, or at, I didn’t feel like I’ve been able to express satisfactorily through painting. And I saw that it had to do with gender and this confusion about my gender. So now, after I made these five paintings for the New Museum Triennial, I realized this, so yeah. I guess I am confused.

GAYDUK: Were there any artists that you find really had an influence on the kind of work you were doing, at earlier points in your life maybe, or changed your perception of what art could be?

SOLANO: It’s difficult for me to answer because I don’t really draw from art that much. There are artists that I admire like David Hoyle, performance artist Terrence Crow, French artist Cédric Fargues who I was very lucky to meet in person and we became friends, and I really love the way he address his references. But speaking of references, I would say the people who really inform my work are not solely artists because their work really has nothing to do with mine or mine with theirs. The real inspiration for my work is myself, and my own person, and my own little Hell. The way I communicate is through pop culture usually, language sometimes, colloquial language. I have a very soft spot for slang and catchphrases and actually one of the two pieces that I’m showing here in Mexico City for the art fair next week is about catchphrases in slang in Mexico City, in Mexican culture, but also in the art world. I made up this phrase that addresses both the art world and everyday, day-to-day language. It’s kind of like a double-edged joke. For my body of work in New York you can expect references to 90s and film and music.

GAYDUK: Like what?

SOLANO: I did a portrait of Michael Jackson that I’m really proud of, and I made a reference to three very iconic movies from the 90s, all of ‘em. And I also painted a portrait of Fairuza Balk. I wouldn’t say I’m a fan of Fairuza Balk, like I really like her in a lot of her movies and actually while I was painting her portrait, my assistant and I were listening to Armed Love Militia which is Fairuza Balk’s band. They’re good actually! It was a very nice experience, finishing that painting and listening to her music, her voice, and reading about her. I’ve been painting her because she’s so iconic right? She had this phase that if you were alive in the 90s and watched any of her films, even for just an instant, you remember her face, her smile, her eyes. She kind of like bursts at you, she jumps at you through her face, and I love people like that, I love faces like that. I’m obsessed with iconic faces, and she’s one.

GAYDUK: Now, most of these faces I imagine you have to recall them from memory, and memory is often very subjective. How does that change things for you?

SOLANO: It’s bittersweet. My entire brain is visual and will be visual for the rest of my life. My memory is visual. When I was in high school, I realized that I memorized my notes because I could remember what they looked like. I remember what the page looked like. I have an almost photographic memory, and even to this day I can walk into a room and remember what it looked like. Or I can listen to a movie and I remember what it looked like. I remember so many details from so many things I saw and they’re going to be with me for the rest of my life. And it’s a blessing and a curse at the same time. But also, blindness has brought new things to the table. Like my experience of music is changing, and my experience of my own body and my sense of touch is changing, and my experience of other people is changing. Like intimate contact with other people is very different.

GAYDUK: So you’re still experiencing art. You just experience it—

SOLANO: I’m not. No.

GAYDUK: I guess, if we consider music and dancing art, besides visual art, you are still experiencing art, but with different senses and if you’re using threads or pins in your painting it is in itself, a kind of artistic experience.

SOLANO: It is.

GAYDUK: When you’re tracing a painting you’re using your hands, but are you also experiencing it visually?

SOLANO: Yes, I do get a visual image in my head of my paintings, but I know that I’m not to ever trust that image. And it changes a lot and that makes me means I need to be very careful who I get feedback from and how I react to that feedback. Because I can be making a painting and I add something and then I ask someone, “hey, can you see this?” and they say yes. Or “can you make out the makeup?” and they will be like “oh, I thought it was blood.” And so I think I screwed up, but then I show it to somebody else and they do think it’s makeup. So maybe it does look a little like makeup. And it changes my image when that happens and I get feedback that I don’t expect.

My image of the painting changes dramatically and that’s very distressing for me. It’s funny, because I hear my reaction is panic. So yeah, the irony is that the thing I have to do is paint and that’s the art I enjoy the least these days … People tend to refer to me as a painter, but I work in performance and video and writing and painting and music and a number of things! And neon, and one of the pieces for the art fair here, is a neon sign. And the other is a text piece. I think I already am in an interdisciplinary place but I want to keep my work as interdisciplinary as I can.

GAYDUK: I was wondering if you were familiar with any other blind artists, like Eşref Armağan.

SOLANO: Yeah, I mean, not a lot. Even to this day, I’m really ashamed that I don’t know a lot about blind art. In fact, the New Museum Triennial is the first time that I’m working with an audio guide for my work. I think it’s really big, making my work more accessible.

GAYDUK: When you record an audio guide for a painting, what do you say?

SOLANO: That’s a very good question and I don’t know. [laughs] It’s so late to figure out. I need to describe the painting but I would say that other blind people might benefit more from story, from hearing the story behind the work than from hearing how the work actually looks. Which obviously that counts. But as an artist and as a blind person, I find more and more that when I meet other artists and they describe their work for me it doesn’t really stick in my brain, what does stick is when artists tell me where the work is coming from. I find that I relate to the artists rather than the art. So I think what I’m going to do for the audio guide is explain that there’s a reference from a movie or a music video and then explain why I chose that reference, why that reference is personal, why it’s relevant to me on a personal level. Because at the end of the day, my work is very personal.

GAYDUK: Do you feel empowered on your journey to overcoming the loss of your sight?

SOLANO: If you had spoken to me maybe three weeks ago, I would have said no. But yes. I would say that yes, I do feel empowered in my creativity, in being able to harness my creativity, and have that creativity send me places. That’s one of the most empowering and fulfilling experiences of my life, this is what I wanted to do. It’s always really heartbreaking that I’m not there to see it, but yes, I do feel empowered. And obviously there is such a great deal that I still need to accomplish just so that I’m able to feel safe. So in that sense, I keep forgetting my own power, I keep forgetting my own achievements, but I’m well aware that I need to keep working very, very hard.

GAYDUK: And if you can describe your upcoming work in three words, what would they be?

SOLANO: Ferocious, silly, and emotionally charged.

“SONGS FOR SABOTAGE” RUNS FROM FEBRUARY 13, 2018 THROUGH MAY 27, 2018 AT THE NEW MUSEUM.