Inside the Impenetrable Mind of Andy Warhol

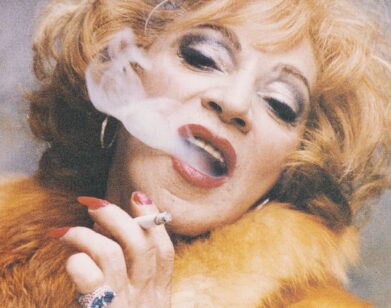

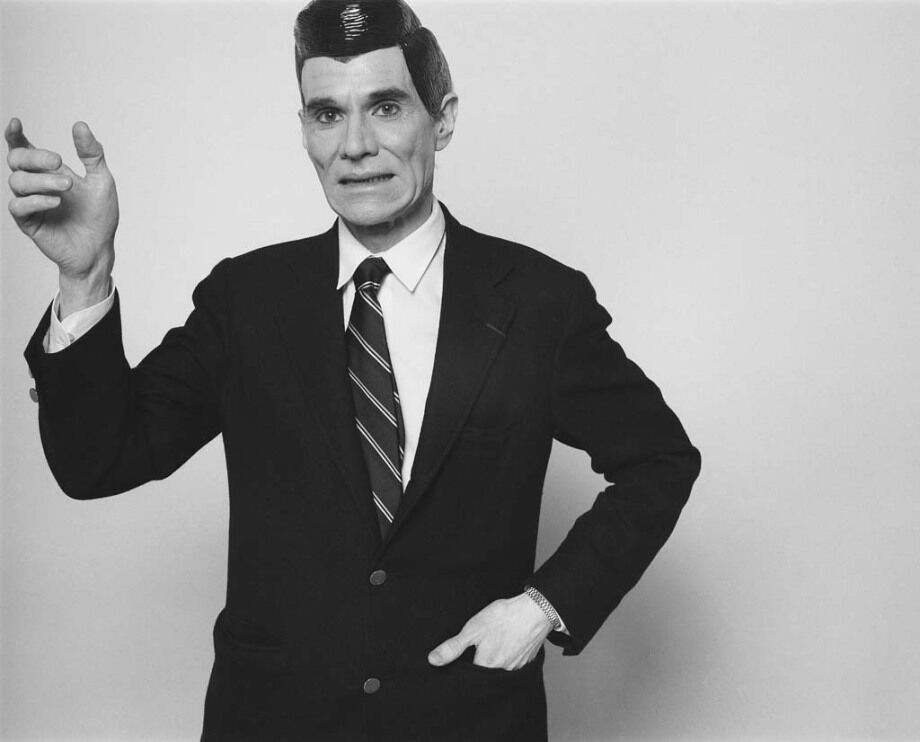

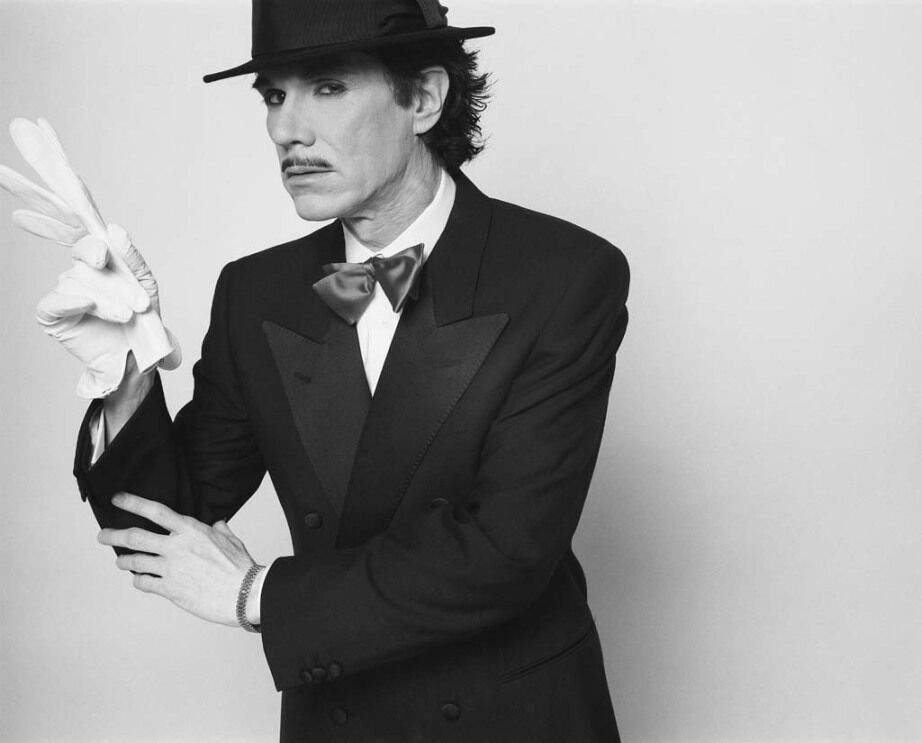

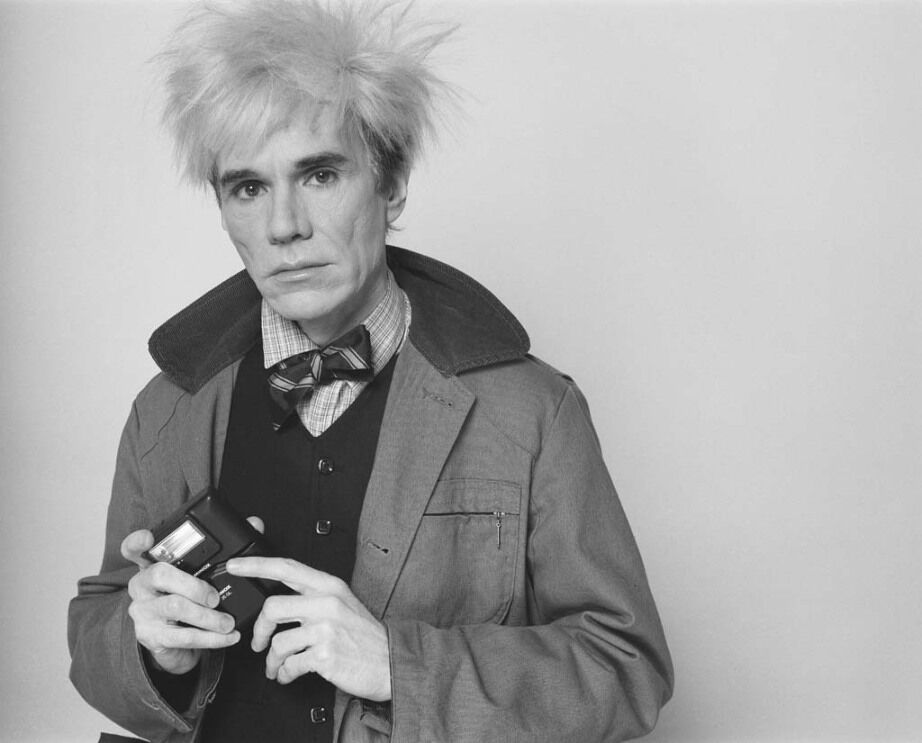

Andy Warhol by Pierre Houles, 1982.

As clearly and palpably as Andy Warhol has embedded his image and philosophies onto our modern culture, he has remained something of an enigma. Perpetually misunderstood and nearly impossible to pin down, he has eluded biographers for decades. Enter Blake Gopnik, the Warhol expert who spent a decade as the chief art critic at The Washington Post. Gopnik’s gargantuan profile of the artist, simply entitled Warhol (Ecco Books), spans nearly a thousand pages, unparalleled in its dedicated documentation. The author spoke with Interview about the many Andy Warhols that existed between 1928 and 1987—and who he remains to the world today.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: You’ve obviously written extensively about Warhol’s art and his life over the years. Tell me about what brought you to write this book. How long in total did you work on it?

BLAKE GOPNIK: Well, the truth is, it was a kind of obvious project. Warhol’s one of the greatest figures of 20th century art. And yet the biographies that existed were either very short or written right after his death by journalists. So it seemed that there was an opportunity to write something substantial and seriously researched. And that, I think, is a fair description of what my book is about—because I spent about seven years on the book, digging in awfully deep.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember the first work by Warhol that you ever saw, or the first one to really make an impression on you?

GOPNIK: That’s a really, really easy question to answer because when I was a kid, we always had a poster of one of Warhol’s very earliest Marilyn Monroes up in the bathroom of my parents’ house. I spent some considerable time looking at a Warhol from the very youngest age.

WILLIAMS: I think Warhol can be one of the most frequently misunderstood artists. I remember going to the Whitney to the overview of his work a few years back and I heard from a couple people that I was with, “Well, he just sort of did the same thing over and over,” or that he took one idea and kind of ran it into the ground. What’s your reaction to a statement like that?

GOPNIK: Well, one of the great things about Warhol is the range of responses he gets from people. I think that’s really important. He appeals in a very, very direct way to people who know absolutely nothing about art. And yet people who know a vast amount about art can spend hundreds and hundreds of pages digging into him. I think he’s one of the hardest artists to pin down. I’ve spent seven years trying to do it, and I can’t say that I’ve done it at all.

WILLIAMS: How important was it to you to, I don’t want to say to strip back Andy’s wig, but to drive home just how integral the self-construction of his persona was?

GOPNIK: I think the biggest surprise, for me, was to discover that Warhol obviously is a genius, but he’s a kind of old-fashioned genius. That is, he’s just unbelievably intelligent. He’s not an academic, but he’s a fiendishly smart person in a fairly traditional sense. He did very well in school. He got lots and lots of A’s. He was on the honors list in high school. So the whole, “gee whiz,” almost silent persona is a complete construction. In the ’50s, he’s a gay, fabulous window dresser. In the ’60s, he acquires this leather-jacketed, sphinx-like quality. In the ’70s, he becomes a new conservative. So he keeps changing who he is, and none of them, I think, are completely the real Warhol. He wanted to be on the cutting edge, and that required constant changes in his persona. It required all sorts of crazy gymnastics in the art that he made. He was just a really interesting person who, above all, wanted to be interesting. If there’s one thing that Warhol couldn’t stand, it was being boring, or cultivating boring people or looking at boring art.

WILLIAMS: Do you think the public underestimates Warhol’s intelligence?

GOPNIK: It’s certainly true that a large segment of the population has bought into Warhol’s constructed personas, because there were lots of them. But he would have liked that. I mean, the point of building a persona is to have people buy it, in a sense. But I think even the general public knows that there’s something slippery going on. In the 1960s, the constant complaint about Warhol is that everything he did was a put on, but they couldn’t figure out exactly how he was putting them on. They couldn’t figure out how he was deceiving the public. That complexity is really important, and I think today’s public can figure that out. They’re perplexed because he’s so different from most great artists that they might come across. He refused to climb on a high horse. He refused to be a figure of obvious poise and hauteur. But he actually was someone incredibly sophisticated, and it was only by launching himself into popular culture that he really achieved his greatest Pop Art. And I capitalize Pop Art. He was an artist. He was a serious high artist at all times, but he realized that the most interesting high art he could make was to actually enter into pop culture, in a way that Lichtenstein with his comic book paintings, or Claes Oldenburg with his enlarged objects never really did. They were always high artists fishing in popular culture. Warhol went much deeper than that. He really jumped right into pop culture.

Andy Warhol by Pierre Houles, 1982.

WILLIAMS: You wrote that “everything he did could be seen as being between quotes.”

GOPNIK: I hate to say it, but it’s one of the great clichés of Warhol from very early on—people realized that his construction of a persona was part of his art-making. But the thing that makes it more than a cliché is that it was also the absolutely most avant-garde position in the mid 1960s. I don’t think people realize that, but Joseph Beuy’s notion of social sculpture was on the cutting-edge. Because you didn’t make objects, you participated in culture as your art form. And that was true of lots of really interesting artists who were largely forgotten today. A guy called Alberto Greco—his final work of art was writing “the end” on his hand and committing suicide as a work of art. It was this extreme desire to collapse the distinction between art and life. And Warhol was right in the thick of that. So, when he was constructing his persona, that wasn’t a trivial act. That wasn’t the same thing as Elvis Presley constructing his persona. It was something that was extremely considered and obviously part of the most cutting edge art of the 1960s.

WILLIAMS: You could also tie it to his sexuality.

GOPNIK: There was no obvious way to be gay when Warhol was growing up in the 1940s, or the ’50s or ’60s for that matter. There was no natural way to be gay. You couldn’t just say to yourself, “I’m gay and that’s fine.” You had to adopt a persona. You were forced to by the culture. One of the most important discoveries I made about Warhol was just how intolerable it was to be gay in Pittsburgh in the 1940s. To come out as gay as a young man in the late ’40s in Pittsburgh was a nightmare, because Pittsburgh may have been the worst place in North America to be gay. While Warhol was in college, the Pittsburgh Police founded a special squad whose only job was to persecute gay people. In fact, in the first two weeks of the creation of this squad, they shot two gay men. So, coming out for Warhol in the late 1940s in Pittsburgh was an extremely vexed part of his life. And that, I think shaped all of his art thereafter, because he had to figure out how to be Warhol.

WILLIAMS: So, given this really deeply complex, potentially liminal sense of authenticity that he had, was it difficult for you to build this concrete portrait of him?

GOPNIK: The thing that I really tried to do was not to tie him down. Not to say “here’s the real Warhol,” but to let the reader watch him building himself. If Warhol is his own greatest work of art, then I wanted to do art history—I wanted to let people watch this work of art he made. I wanted to pull it apart the way an art critic pulls apart a painting. I wanted to say, “Here’s how to read this strange persona.” I wanted my reader not to come away with a fixed notion of Warhol, but to come away with an understanding of that construction of persona over time.

WILLIAMS: It does seem like everybody has their own Warhol, or that everybody knows their own kind of version of him.

GOPNIK: Yes. Everyone has their own Warhol. Unfortunately, the Warhol of many people, including some scholars, is based on erroneous facts. And even though I wanted to write a very art critical biography of Andy Warhol, I also wanted it to be just chockablock with new information. There are more simply erroneous myths floating around about Warhol than you can imagine, and I wanted to demolish as many of those as possible.

WILLIAMS: What are some misconceptions that still come up about him?

GOPNIK: One that’s very important is the notion of him as being asexual. I have medical evidence of his fairly significant sexuality. I can count 13 sexual partners that he had that I know of. And I’ve interviewed a lot of them. Now, that’s not a huge number for an out gay guy in the ’70s or ’80s, but many of us have slept with fewer than 20 people. So, it’s actually a normal sexual life.

WILLIAMS: Benedetta Barzini told me that Andy thought of the people around him as cockroaches and that they were just desperate to please him.

GOPNIK: I certainly don’t believe that Warhol thought of the people around him as cockroaches. I think he saw them much more as anthropological subjects. Sometimes I like to talk about them as art supplies. That is, they were part of what it was to be a pop artist. He was observing pop culture, and they were an important part of the new underground that was so important in pop culture in the 1960s. So, I don’t think he was nearly as close to a lot of those figures as people imagine. Even Edie Sedgwick—he went out with her a lot, but I don’t get a sense that they were friends in any kind of deep sense. They were just people who hung out, who went to parties, who above all were in the gossip columns constantly.

Most of the people at the Factory were more or less casual acquaintances of Andy’s, to whom he was more than half decent. Certainly Billy Name, who was one of the people he was closest to—the guy who photographed a lot of the Factory activity—never had a negative word to say about Andy. I was lucky to interview him for, I don’t know, six, seven hours before he died. And he was just full of praise for Andy Warhol. Almost all of us are seen very differently by different people in our lives, some of whom probably dislike us intensely and other people love us. I don’t think Andy’s any different.

Andy Warhol by Pierre Houles, 1982.

WILLIAMS: Andy initially conceived of Interview as a film magazine. Do you think he would’ve foreseen Interview lasting as long as it has?

GOPNIK: I think he realized that Interview was going to be a very major venture in the history of publishing. I don’t think he’d be surprised at all. He might’ve been surprised that it hadn’t changed more over the years, because there’s certainly continuity between today’s Interview and the Interview that he founded. Not the film magazine of 1969, but by the late ’70s, I think there’s continuity. And I think he would’ve been pleased to see Interview continuing in this tradition that he began.

WILLIAMS: You wrote that Chelsea Girls “foreshadowed the ADD that smartphones brought to the 21st century screen-time.” Other films of his, like Sleep or Empire, meanwhile, are devoutly rigorous and structural. In a day and age where people seem to be intimidated by something like the three-hour runtime of The Irishman, do you think that there’s a case to be made for the value of boredom?

GOPNIK: I sat through all eight hours of Empire, and have to admit that I wasn’t bored for a second. And I am certainly as capable of boredom as anyone else. I mean, I once spent a week looking at Velazquez’s Las Meninas. Great works of art do repay that kind of attention. I think we’re in a cultural moment where we’re split between extremely short attention spans, but also a willingness of people to dig in deep when they’re digging in deep. Look, my thousand-page biography of Andy Warhol is getting some pretty decent reception. There are moments when you think Warhol had the world’s shortest attention span, but there are also moments when you realize he was really willing to go slow. And you could say that that split in the kind of attention his art demands does really foreshadow where we are today. Whenever a museum shows all of Empire, all of Sleep, there are always a few people who stay for the whole thing.

WILLIAMS: I put it on in my apartment. My roommates wanted to kill me. But watching Empire, I do think there’s a plot there. Or, if not a plot, a narrative.

GOPNIK: You could say there’s a narrative. Time is the narrative and time is at the heart of all narratives. Just by virtue of him pointing a camera at the Empire State Building and watching what happens, you get a narrative. As you watch, you’re watching Empire, but you’re also watching your mind at work. You’re also watching your own attentiveness—when you start noticing the grain of the film and how it changes over time, or you start thinking about your own thinking about the film. Those durational movies, they clearly repay the most serious looking, as any painting does. But Warhol was also constantly saying that they could also be on in the background. He liked to compare them to a fireplace.

WILLIAMS: I see Empire as almost like a window.

GOPNIK: A window is very interesting, because after the invention of perspective, all paintings become windows. I like to compare his society portraits of the ’70s and ’80s to Goya’s portraits of the idiot Bourbon royalty of the early 19th century in Spain. Both Goya and Warhol, you look at them and you realize they reveal the emptiness of so many of these figures. The self-importance. Warhol’s completely in the tradition of secretly satirical portraiture, I think.

When Warhol first showed those soup cans, they were really seen as anti-American, even as anti-consumerist. He was criticized from every possible political angle. He’s pretty straight forwardly a middle-to-far left figure in terms of his politics, and that comes across clearly in the institutions he gave money to. There’s lots of thank you letters from left-wing causes to whom Warhol has contributed either a work of art or money. He certainly was not someone who in any straightforward sense celebrated the worst sides of consumer culture.

WILLIAMS: Are there any artists, or an artist in particular in our current moment, that you think has come close to inhabiting the world as a pop star, like Andy did?

GOPNIK: Damien Hirst is someone who is deeply aware of Warhol and is the first person to admit the influence of Warhol on his work. He often achieves a similar complexity in the way that he participates in pop culture and does things that look kind of icky on the surface—selling a hundred million dollar diamond skull. But his works have also seemed to have critiques built into them. Anyone who comes after anyone is not the equal of the person that they come after. So, I don’t think Damien Hirst is as important for art history as Andy Warhol, but he’s a very major figure for ’80s and ’90s and even 21st century art. And he certainly is swimming in the same waters as Andy. And Jeff Koons, though Jeff isn’t quite as self-aware as Damien Hirst. He has that same duality that Andy did, where you’re never sure if he’s putting you on or not. Or if maybe he’s not putting you on, but in fact he is putting you on, and he doesn’t even know it.

Andy Warhol by Pierre Houles, 1982.

WILLIAMS: Do you think that’s the same as creating a character, though?

GOPNIK: Certainly both Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have very, very prominent public personas. They don’t change them. They’re more like Salvador Dali or Frida Kahlo, in that they create a persona for themselves and live in it. Warhol changed it all the time, and you were never quite sure if he was inhabiting the persona or if it was a mask that he put on. I do think that Warhol being gay makes his adoption of personas more complex than Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons, just because they’re straight. I think that being gay automatically lends a complexity to the construction of self that just isn’t there for heterosexuals. Or it wasn’t until very recently available to gays in the same way.

WILLIAMS: I would argue that it definitely makes you more interesting.

GOPNIK: Warhol always was interested in transgression. I mean, he wore nail polish in college. He was really quite flamboyant a lot of the time in art school. Being gay allowed him to inhabit transgression very directly and easily. And he was always interested in transgression in his own art, in the people he had around him. To appear on The Love Boat when you were supposed to be a major figure in art history was an automatically transgressive act. Much more transgressive than just living in a garret, or some cliché like that of the artist. Or, for that matter, having existential angst. If you really wanted to transgress as a great artist, appearing on a television program as stupid as The Love Boat was a guaranteed way to do it.

WILLIAMS: Would you say that the Love Boat thing is also an act of camp?

GOPNIK: It’s clearly camp, and camp is central to understanding everything that Warhol ever did. Outsiders feel that camp is pure performance, but camp is also a way of living. I think it’s part of who Warhol really is. Camp is a really complicated concept, and we haven’t come to the bottom of it, I don’t think.

WILLIAMS: I would say, just like Warhol, given last year’s Met Gala, people still don’t really understand it.

GOPNIK: I think the Met Gala wasn’t a great example of camp, because its tongue was too far in its cheek. People acted as though camp was an easy category, but they weren’t really living the category of camp. Because for camp to be real, it has to be transgressive. It has to be difficult. And I hate to say it, but once the Met can have a camp gala, you know that camp has lost some of its power.

WILLIAMS: If you enshrine it in a museum…

GOPNIK: It’s no longer camp. It just isn’t. The other thing about Warhol is that, certainly with his pop art objects, they are worth looking at. They’re complex visually. They function as paintings, even while they function as pure conceptual art, and that’s unusual to have things operate on so many different levels. They also work really well as posters in your parents’ bathroom.