Barbara Kruger

I have problems with a lot of photography, particularly street photography and photojournalism. There can be an abusive power to photography. Barbara Kruger

Readers flipping through the front section of The New York Times on Saturday, November 24, 2012, might have come across, on page A21, in large white Futura type on a black background, a piece from artist Barbara Kruger. Under the title “For Sale,” the work read: “You Want It You Buy It You Forget It.” This newspaper-embedded artwork was particularly apt because it appeared on a weekend that was kicked off by Black Friday, one of America’s busiest shopping days of the year (and also, in some years, one of its deadliest). So on that morning, the Barbara Kruger piece functioned exactly as Barbara Kruger pieces have so often functioned since the 68-year-old artist first began working with invented texts in her art in the 1970s. The direct address is disarmingly direct. Certainly, the “you” implicates the reader—a shopper, a consumer, a part of the capitalist enterprise, guilty of impulsive buying habits. But the “you” is also a general composite—that annoying, far more guilty everyperson-and the reader sides with the artist in condemning this sector of the population who is greedy, wasteful, and irresponsible. So already—and almost always in a graphic Kruger text piece—a haunting repositioning occurs in the mind of the viewer: judged and also judging; agreeing with the charges even as she or he is charging others.

Kruger’s spectacular corpus, spanning four decades, is often described as political—and it is. But just as much it creates these moments of internal identity confusion in which we don’t know if we are acting as victim, oppressor, or witness. Usually, we are all of the above.

Two weeks after the New York Times piece ran, a recent work by Kruger could be found on a wall at Art Basel Miami Beach, alongside convention-center booths showing works by her contemporaries—many of whom have been her peers since the ’70s in downtown New York. On the aluminum-mounted vinyl was printed: “Greedy Schmuck.” Art Basel visitors must have passed this startling graphic accusation and had the same interior rift that I did: “That is about me because I’m participating in this hysterical culture of art-buying. I am the greedy schmuck.” And at the same time, “No, the greedy schmucks are all around me, the ones selling and the ones buying and the ones making the huge profits. I’m just passing through. Yes, that painting is correct; these people are greedy schmucks!” This is how the meaning—and re-meaning—of a Barbara Kruger builds and builds and builds. There is a distinctly Krugerian tone to all of her pieces—”Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face,” from 1981; “Not Cruel Enough,” from 1997; “Plenty Should Be Enough,” from 2009—that compels the viewer to side with her and against her simultaneously, and always stop as the balance of our thinking shifts.

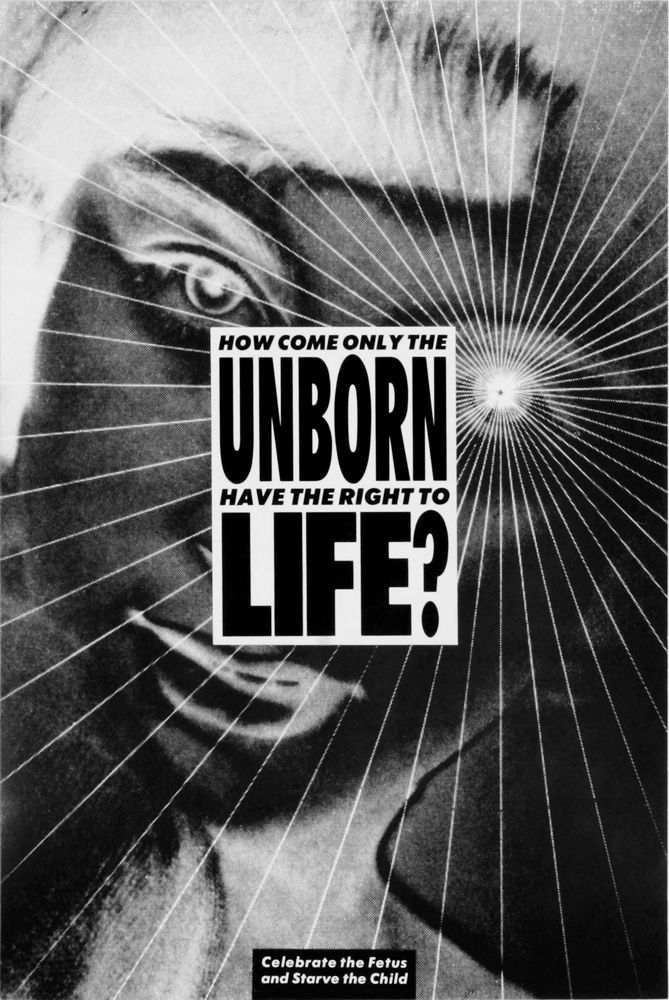

Kruger famously—and perhaps, at first, inadvertently—got her training as an artist the hard way: through a full-time job as a magazine designer at Condé Nast, starting out at Mademoiselle. And while some of those early layout techniques of bold graphics inform her work, a pulsating visual-linguistic triple-take keeps all of her pieces so alive that she’s become known for her own immediately identifiable, authoritative style—even if authority is what is being questioned in the authoritative typeface. Her work has promoted a march on Washington for women’s reproductive rights with the iconic “Your Body Is a Battleground” poster in 1989 [Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground)]; swallowed buses with wrap-around vinyl; taken over the exterior of a department store in Frankfurt, rendering a giant eye across the building’s façade; is currently sliding across the sides of escalators of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in the nation’s capital; and, premiering this May, will be cloaking the bodies and backdrops of ballet dancers for choreographer Benjamin Millepied’s gem-themed ballet at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris.

Kruger lives and works in both New York and Los Angeles (where, since 2006, she has taught art at UCLA). I met her in New York for breakfast on a Sunday morning in January at one of her old downtown mainstays, the Square Diner on Leonard Street.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You’ve lived downtown since the mid-’60s, so obviously you’ve seen a lot of change in New York—how it’s increasingly become less of a place for artists and more of a place to show expensive art.

BARBARA KRUGER: Yes, but I’m not into it when people say, “Oh, I remember the gritty ’70s.” I feel like, Oh give me a break. I’m not nostalgic. I can’t stand that. The only scary thing—and this is true with most cities everywhere—is that there’s no room for the working-class and middle-class people here anymore. Tribeca is exhibit A. I moved into this neighborhood in 1967. Nobody lived here. You know, artists did not gentrify this neighborhood. These floors and these buildings were empty. All these small businesses had moved out to Long Island or Queens. That’s when artists appear, right? But when I first came here, the only people who’d been on Chambers Street were Yoko Ono; [acid pioneer] Owsley Stanley; and Ken Jacobs, the filmmaker. I was living in the Village, going to Parsons for a year; I used to go to parties in a building down here on Reade Street where some friends lived. I got involved with someone who had just settled in that building. I think we were there for about two years and then I moved for one year to a building in SoHo, and then in ’70 or ’71, I moved back to a place in Tribeca. But to me it’s symbolic that people take over buildings and luxury lofts. It’s just the way it goes. For a long time, literally, when the roof leaked, it would be fixed with Scotch tape. When AIRs [artists-in-residence, permits which allowed artists to live legally in buildings zoned for manufacturing use] happened, the landlords wouldn’t give an AIR to a single woman. They wouldn’t give artist-in-residence status to women in the 1970s.

BOLLEN: That’s important to note.

KRUGER: That’s the way it was. So you’d stick your bed down in the apartment of a guy who lived downstairs and make believe it was only a working loft whenever the inspectors would come.

BOLLEN: So developers have come to these neighborhoods to transform them into luxury lofts.

KRUGER: It’s all about profit, which is how the culture works. I understand that. So I don’t feel victimized in that way.

My work has always been about power and control and bodies and money and all that kind of stuff Barbara Kruger

BOLLEN: When you go through your studio, do you ever find old work and are surprised or pleased or horrified by what you made 40 years ago?

KRUGER: It feels like I made them yesterday. I remember when I made them. I’m still very much in touch with that the same way you probably feel about your younger self and who that person was.

BOLLEN: When you attended Parsons, Diane Arbus was one of your teachers. What do you remember about her influence on you?

KRUGER: She was really terrific, sort of my first female role model . . . [waiter comes to table] I think they want us to order. [Kruger examines menu with weekend brunch offerings] They have a brunch now? See, this is the Tribecan influence. Fourteen dollars for brunch. [both order eggs] I grew up coming to this diner, sitting literally right here in this place.

BOLLEN: I’m glad it’s still here.

KRUGER: So Diane was one of the first female role models I ever had that didn’t wash the floor six times a day. I liked her as a teacher. It was for a foundation year at Parsons, so it was she and Marvin Israel, who was an art director and designer. They had an influence on me.

BOLLEN: Has photography in general been a big influence on you?

KRUGER: I have problems with a lot of photography, particularly street photography and photojournalism—objectifying the other, finding the contempt and exoticism that you might feel within yourself or toward yourself and projecting it out to others. There can be an abusive power to photography, too.

BOLLEN: But there was a lot of photography coming from the artists you were around in your formative years down here. And a lot of respect for the artist as a sort of radical or mystic.

KRUGER: For me, the idea of being an artist didn’t have to be tied to a bohemè melancholia. It’s because I come from a different class. I didn’t finish college, my parents didn’t graduate college; we didn’t have a pot to piss in. I’m from Newark, New Jersey. I had to work. I didn’t think it would be possible for me to be an artist without having a job.

BOLLEN: And so you did work in the design departments of several magazines at Condé Nast. Was that sort of full-time job enjoyable to you?

KRUGER: Well, enjoyable‘s not a word I would use. [laughs] But I was a kid. I thought, Oh, should I be an artist, what does that mean? It’s not like I knew art history. I studied it at Syracuse [University]. I had a few months of it. But I’d always been into fashion on a certain level and would do fashion illustrations, so it made sense that I’d enter that kind of job. I did freelance fashion illustration for Seventeen and Mademoiselle, line drawings.

BOLLEN: I didn’t realize you were an illustrator.

KRUGER: Yeah. Before I did front-of-the-book design, I did little back-of-the-book drawings, freelance illustration stuff, so I do understand how magazines work . . . [food arrives] Thank you. You’ll notice I didn’t use that L.A. voice thing I hear so much. That Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian drone [high-pitched warble] “Thank you, thank you.”

BOLLEN: Exorbitant whiney-baby cuteness.

KRUGER: The vocal fry drives me crazy. It drives me crazy!

BOLLEN: It’s like a new accent has come into existence and is taking over colleges and shopping centers. Why are people—or at least young women—starting to speak that way?

KRUGER: I’d hear it and I would think, What am I hearing? And then one morning I was listening to Howard Stern, which I’ve been doing for 23 years, and he had just read an article about this thing called “vocal fry.” So he started talking about how it drove him crazy. He watched The Bachelor and all these girls talked like thi-i-i-i-i-i-s. And now there have been academic articles written about it. It’s a self-selecting device that mostly young women use, although there are men that use it, too. It’s meant to sound like cool girls, but every time I hear it, it’s like there’s this big thing on their face that says idiot. There’s a Gwen Stefani commercial for a telephone that’s been on. And there it was in full flair, the vocal fry: “I miss you guys.”

BOLLEN: Is it a Valley accent?

KRUGER: It’s part that and part up talk, which is Midwest. Every sentence ends like this . . . [uplifted into a question] And then you add the vocal fry to it. [laughs] It drives me batty.

The whole decade-izing thing doesn’t work for me . To me, the ’80s began in 1975 and ended in 1984—’84 or ’85 Barbara Kruger

BOLLEN: I read that you were part of a group in the ’70s called Artists Meeting for Cultural Change. But I can’t seem to find very much about Artists Meeting for Cultural Change. What exactly was it?

KRUGER: We met at Artists Space. I was just a beginner in that. It formed even before I joined as sort of a protest against the museums and their dubious doings and politics. Again, I was not a real active speaker; I was intimidated but I was also curious. But there was Kathy Bigelow and Joseph Kosuth, and Mayo Thompson, who had this group Red Crayola, and Becky Johnston, the screenwriter.

BOLLEN: Was it trying to incite some kind of productive protest?

KRUGER: Not inciting. Sort of more a combination of theoretical readings.

BOLLEN: Were you heavily influenced by the works that artists were making around you in SoHo? Was there a shared sense of a project?

KRUGER: Not really. I had done a first show at Artists Space in 1974, and around the same time Laurie Anderson, Barbara Bloom, Jonathan Borofsky, Don Gummer, and other people were showing. But in the early ’70s, I was working at the magazine, so I didn’t have artist friends that I went to school with. Historically what’s happened, since art has been incredibly professionalized, is that artists come from schools, they keep their friends, their cohorts, they stay in L.A. now, they don’t come to New York. But at that time, they came to New York, and I didn’t have that. The group I eventually did connect with, in the ’70s, were the beginning graduating classes from CalArts. So my early art friends were Ross Bleckner and David Salle and, previous to that, Julian Schnabel.

He went to the Whitney program and sublet my place for a summer. And then came friends like Marilyn Lerner and Sherrie Levine and Cindy Sherman, Jim Welling, Nancy Dwyer, Louise Lawler, Sarah Charlesworth, Laurie Simmons, Carol Squiers, Judith Barry, and Jenny Holzer. Richard Prince and I were really close from early on. I met Lynne Tillman a bit later, around 1977. But it wasn’t just people from one school, you know, it was people who came together in the city, and we found ourselves doing work. That was my first peer group.

BOLLEN: Was that a separate world from the magazine work you were doing?

KRUGER: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I was just a designer in the art department and took the subway from Reade Street over here up to Condé Nast when it was at 420 Lex, next to Grand Central. But it was a job. And soon after, maybe about two or three years after I started, I realized, “I’m not cut out to be a designer. There’s just no way I’m cut out to create someone else’s image of perfection as a profession.” Eventually I was doing front-of-book. It was all paste-up-type and pictures using someone else’s photography, and I’m working on putting text on it. That’s why I say my work is substitutional now, because we worked with mock type. It didn’t say anything. It was A-B-C-D-E. I put the type in, pasted it on—we worked on boards. I developed a fluency in that because that’s what my work was. I was totally outside of the art discourse at that time. I remember going into galleries and seeing this thing called conceptual art, and I understand people’s marginalization from what the art subculture is because if you haven’t crashed the codes, and if you don’t know what it is, you feel it’s a conspiracy against your unintelligence. You feel it’s fraud. I understand that. Now that I have crashed the code, I understand and support all this work. But I know how, in many ways, it’s a closed language. My work, not so much so, and it’s not by coincidence, because I just feel I relate to that reader who doesn’t know the secret code word.

BOLLEN: You’ve already admitted to being interested in fashion and design. That might run counter to those coded conceptual leanings.

KRUGER: Even when I was a little girl, I remember going to the Museum of Modern Art. I think my parents took me there once or twice. And what I really remember is the design collection. And when I was very young and just starting at Condé Nast, there were two magazines: Domus, which was a great design magazine; and Nova, which was an English fashion and décor magazine. I used to see these pictures of these apartments in London that these designers lived in and thought, Oh my god. And yet I don’t consider myself a successful designer by any means.

BOLLEN: But you’ve been such an influential artist on design. You’re almost a designer’s artist of sorts. You’ve revolutionized graphic design.

KRUGER: I think that designers have an incredibly broad creative repertoire. They solve. They create images of perfection for any number of clients. I could never do that. I’m my client. That’s the difference between an artist and a designer; it’s a client relationship. And so, to me, it’s not a hierarchical order; it’s not like artists are better than designers, but it is a particular instrumentality, which makes for a difference.

BOLLEN: Would you say there also might be a difference in elocution? Designers work by subliminal powers, to make you want things you don’t realize you needed. But artists are more direct or overt in their messages, or maybe they’re not as manipulative.

KRUGER: I don’t know about that. It has its work to do. I should tell you that my first love has been architecture, ever since I was a little girl. If you look at Picture/Readings [1978]—that book of different architects I did—that is really where my spatial sense and design came from. I was raised in a three-room apartment in Newark, New Jersey. I never had my own room and stuff. But on weekends, we used to exercise our fantasy of going to look at model homes we could never afford, and at that time, all the open inspections had, like, velvet ropes on the bedrooms. I used to draw developments of different model houses. It was sort of an exercise in both refining one’s image of perfection, in terms of the space that constructs and contains you, which I think architecture does, and understanding it as a discipline. One of the thrills about Los Angeles is it was this great bloom of residential architecture from 1917 to 1975-modernism, so-called, which I loved.

I never say I do political art. Nor do I do feminist art. I’m a woman who’s a feminist, who makes art. But I think what becomes visible and what work remains absent is always the result of historical circumstance. Barbara Kruger

BOLLEN: When you started your word-on-image pieces, there were other artists also utilizing words or language in arts. Did you find a receptive audience to the messages found in your works?

KRUGER: I remember going into a gallery and seeing a Lawrence Weiner show. I just didn’t get it. Now that I’ve been educated in conceptual art, I understand it. I think the difference was that my photo work with words comes full-on from my job as a magazine designer, not informed by the art world at all. That was the shock when I first showed it. They were bigger; they were one of a kind. I couldn’t make an edition; I didn’t have the money. I used to take them from a photo place on 53rd Street onto the E train. They were, like, 48-by-72-inch, and I’d carry them in the subway and up the 78 steps to my studio. I first showed that work in L.A., at Gagosian. I had two shows with Larry, in ’81 and ’82. And that was the first time people bought my work. And he worked in New York with Annina Nosei, and she had a gallery on Prince Street, and I had my first show of that work with her. Sold out immediately. I made $75, maybe $80, on each of those works. They sold for $1,200; I got half, but I paid for the frames and the prints.

BOLLEN: The text in many of those pieces have taken on many lives of it own—”I Shop Therefore I Am.” In making those pieces, was the text something you wrote separately, or did that happen in the studio, in immediate relation to the found image? What’s your writing process?

KRUGER: You know where I used to go a lot? I used to write all of my Artforum columns at Caffè Dante on MacDougal Street. That used to be my office. I used to write there a lot. I’ve always been a café writer—not with a computer, but with a little pad and pencil.

BOLLEN: And how did you know which image would work with the text you wrote?

KRUGER: Sort of a mix and match. I have a repertoire, an archive, as they say today, of images.

BOLLEN: Is your archive culled from magazines?

KRUGER: From hunting and gathering, yeah. You know, it always gets me when people say that I worked in advertising. I never did. I never had that experience of selling a particular product. When you work in magazines, it’s a serial process, it’s about seriality—and so is photography. Or painting. It’s about serial productions. And it’s true with amassing an archive—a seriality of images, a seriality of texts. And it’s the same with my video work. It’s about the multiplicity of images.

BOLLEN: Feminism is a part of your work, but do you ever feel as if critics are trying to tie you down to a certain politic—’80s feminism, that’s Barbara Kruger—instead of letting your works live multiple lives?

KRUGER: First of all, the whole decade-izing thing doesn’t work for me. To me, the ’80s began in 1975 and ended in 1984—’84 or ’85 is when the market changed, when things really heated up. For me, decades are weird. Artists always are a reflection of the times they have come up in. And I think that, for us, there was a real historical change, and it was the first time that women had entered the marketplace, that their works had not been marginalized. I didn’t show my work at A.I.R. [A.I.R. Gallery, a pioneering artist-run women’s gallery], at the women’s gallery. Most of the men I came up with were colleagues and peers; they supported my work.

BOLLEN: So you don’t feel pigeonholed by that kind of association?

KRUGER: I never say I do political art. Nor do I do feminist art. I’m a woman who’s a feminist, who makes art. But I think what work becomes visible and what work remains absent is always a result of historical circumstance, you know—hard work, to some degree, and social relations. That sort of strange happenstance of luck, about who knew who, and who is connected . . . That’s why I curated the show at MoMA years ago that nobody even thinks about anymore, “Picturing ‘Greatness’ ” [1988], where I went through their portrait collection. I had these photos of famous artists and the text script was about “How is fame produced?” or “How is value produced?” This is something you really feel now, where things have changed so in the past. When you talk to dealers, you realize that not that many people come around and want to buy art because they love art. There are very few speculative bubbles left, and the art world is one of them. So it’s really about buy and flip, or, like the work I did recently, buy low, sell high [Buy low sell high, 2012].

BOLLEN: I was at Art Basel Miami Beach last December. It would probably make me a less cynical person if I skipped that week, but I remember one of your works at the convention center, “Greedy Schmuck” [Untitled (Greedy Schmuck), 2012], screaming over all of the partitions and paintings and bald heads. I love that your work continues accumulating new and accurate meanings each time it is hung in a different context. Certainly that was the case for “Greedy Schmuck” at Miami.

KRUGER: It’s funny because I remember one critic in around 2002 or so wrote about my “I Shop Therefore I Am” piece from ’87 [Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am)] and said things are so different now than they were when I made that work. But that is completely wrong. Things are like they were but multiplied in terms of the intensity of commodity culture and how the digital world has intensified that to a certain degree. One of the real crises of how things have changed began with hip-hop and sampling. You know, I never call myself an appropriation artist. Critics do that. But the issues around copyright and so-called intellectual property, which, for me, is a euphemism for corporate control in so many ways . . . I believe in copyright. I do. But it’s been taken to such lengths. Remember when Donald Trump wanted to copyright the phrase “You’re fired”? And then there’s this guy who killed himself last week, Aaron Swartz [26-year-old computer programmer and advocate for freedom of information over the internet who had been under indictment on federal data-theft charges] . . . These are contentious issues. I’m not saying there’s an angel and a devil in them. These are huge issues today and they’re something artists have dealt with constantly, whether it’s sonically, through music, or visually. When the record industry won the Napster kerfuffle, you knew that was a Pyrrhic victory. You knew they had won but they had lost. Think of the amount of time it took for record stores to collapse. And publishing is in a similar crisis. And movies, too, even though they’ve had a good year.

I THINK THAT DESIGNERS HAVE AN INCREDIBLY BROAD CREATIVE REPERTOIRE. THEY SOLVE. THEY CREATE IMAGES OF PERFECTION FOR ANY NUMBER OF CLIENTS. I COULD NEVER DO THAT. Barbara Kruger

BOLLEN: There have been moments where you’ve applied your work directly to political movements and events. “Your Body Is a Battleground” was originally done as a poster for the 1989 pro-choice march on Washington. Many artists fear mixing their work with anything overtly political, for fear of it reading as propaganda.

KRUGER: My work has always been about power and control and bodies and money and all that kind of stuff. Sometimes you can be broad, but that time I wanted to be more specific. I also did that text again without the words that said where to meet on the lawn.

BOLLEN: I’m always stuck by that image of “Your Body Is a Battleground” as a billboard on a street in Columbus, Ohio, that was right next to a pro-life billboard of an eight-week-old fetus . . .

KRUGER: Their billboard went up 12 hours after mine did. They saw it and responded.

BOLLEN: So theirs went up second! I wasn’t sure who was responding to whom, but together it makes such a powerful moment of cultural provocation.

KRUGER: There was an ad for car insurance or something when I initially put it up. But yeah . . . And it’s still an issue. I’ve gone back to Washington and I just cry—oh my god, this is about something so much bigger than a fetus. I’ve done lots of work about abortion and domestic violence.

BOLLEN: It seems like in your career there’s been this constant panning out, from individual works to streets to buildings to newspapers to commercial products to installations in the earth. And you haven’t been reticent to use the latest technology.

KRUGER: I’m very fortunate that my work reproduces very well. And because I worked at a magazine, I really do understand what it’s like to have a short attention span. I have a short attention span. So, for example, in my time-based videos, I make sure there are always places to sit. People walk in and they walk up; they come in and they sit down if a seat is available. You just try to figure out instrumentally how the work does its work and what’s the most congenial site for it. How to make it meet the viewer’s eye, you know?

BOLLEN: It amazes me that your work has swallowed whole buses and buildings and has become part of the landscape of skylines in terms of billboard signage.

KRUGER: Early on when I had no money I wanted to do a billboard and I called a company up and they said, “What are you selling?” They couldn’t understand what I wanted to do. I was lucky to have early support from places like the Public Art Fund, which allowed me to do projects I never could’ve done on my own.

BOLLEN: Like those “Help, I’m Pregnant!” posters in bus shelters [Untitled (Bus Shelter Posters), 1991]. I noticed those were done in a different font from the work before. Do you have a formal rule about your fonts—which ones you use and for what?

KRUGER: Whatever works!

BOLLEN: When you do bus posters or billboards or digital screens, your works are purposely placed at the site of advertising. Do you follow the evolution of advertising? I think it keeps getting wittier and funnier, and I wonder if advertising becomes more a threat to art or if it makes it harder to compete in a public environment?

KRUGER: It’s always been so clever and smart. When you go to London, for instance, advertising has always had a really elevated place in culture, much more so than here, and things are even wittier there. Most advertising is schlock here, but a lot of it is witty and great, and I admire it tremendously.

BOLLEN: You did the exterior of a department store in Frankfurt and, last year, the lobby and escalators of the Hirshhorn Museum. Are there any new arenas where you’d like to apply your text works?

KRUGER: I have a project in May in Paris with Benjamin Millepied. He’s invited me to do the stage sets and costumes for a ballet. We’re meeting now. And David Lang, who did The Little Match Girl Passion, he’s doing the music.

I remember going into galleries and seeing this thing called conceptual art Barbara Kruger

BOLLEN: Can I ask you about your decision to resign from the board of MOCA in L.A.? [Last July, weeks after the forced resignation of chief curator Paul Schimmel, Kruger, along with artists Catherine Opie, John Baldessari, and Ed Ruscha, resigned from the board of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.]

KRUGER: It wasn’t really my decision. I didn’t want it to play out that way. I don’t know if you read the letter signed by Cathy [Opie] and me. That’s how I feel. And in that letter there was no accusatory bad guy versus good guy, which is the way it was played in the press. Not all the press, but some of it. I think it’s a very complicated issue. I’ve known Jeffrey Deitch for 30 years. I had the first show in his Wooster Street space of my first multiple-channel video, Power Pleasure Desire Disgust [1997]. I have tremendous affection for Jeffrey, and I think Eli [Broad, MOCA founding chairman and life trustee] has built an incredible collection. He’s a great supporter of the city of Los Angeles. He’s a Democrat. [laughs] I think there are complicated issues at work, but the real complicated issue is cultural funding in this country and what happens when philanthropy is reduced to speculation. How do institutions survive? In New York and in the European cities it’s one thing if you want it based on attendance, which I think is ridiculous for cultural institutions, but in the denseness of certain cities, it’s at least possible. In L.A., you cannot run an institution that way. Attendance is not a measure; it cannot be a revenue stream for the success of museums, and MOCA has always had this great curatorial, critical program, which has made it different than any other museum. And I want it to stay. But you can’t get people to fund intellectually ambitious, non-art-star shows now. It used to be different. There are a few people who will fund it, but they want their horse in the race; they want their artist in the show. I think MOCA is a great institution—I want it to continue. I think all the players in that game really want the best for Los Angeles. It’s a great city to be an artist in—the American city to be an artist in, in many ways. It’s much more affordable. It’s where the art schools are. It’s like London. It’s an art school town. I love New York, so it’s not a New York versus L.A. thing. But [L.A.] has great museums and great museum directors and more and more galleries, which I think is puzzling because it’s a difficult place to sell art. I should say that in my leaving, Cathy and I were never told that John was leaving the board. I read it in the press. I wish it hadn’t happened that way. Enough said.

BOLLEN: Okay. No more on MOCA. How about the influence of galleries in the art world, or rather, their growing need to self-multiply into global brands and constantly sell, sell, sell at any and all art fairs. Is art suffering on the chain of supply and demand?

KRUGER: First of all, most galleries are less empowered than they’ve ever been in terms of these art fairs. Galleries are interesting because they’re free for people. You don’t have to pay $12 to walk in the door like you do at a museum. It’s expensive to go to museums! But dealers who go to these art fairs frequently can’t sell work to people unless those people can look up the history of the artist and see what the secondary market sales are. It ain’t fun for a lot of dealers, either, even though they make money. But that’s because there’s this bubble that still exists, especially for those of us who’ve been fortunate enough to have won the lottery for 20 minutes. But I see it as all temporal, so arbitrary.

BOLLEN: I’m surprised you don’t have a problem with your art being sold in a convention center.

KRUGER: To me, the art world is an anthropology, right? My parents traded their labor for wages. You have to live inside of capital unless you have a huge inheritance and can afford to have these pipe dreams. Most artists will never make money off their work, but that spark, that need to create commentary, to visualize, textualize, and musicalize your experience of the world will continue whether it’s a hot commodity or not. You see that places where that need is shut down, we see oppressiveness and subjugation. That need to create commentary is huge. Most of that commentary will not make a big flip profit for some guy buying a condo on the next block. You have to go in knowing that. When I came up in the art world, it was twelve white guys in lower Manhattan with maybe two women—two visible women. Now it’s much better. People who are calling themselves artists are people of all colors and persuasions and genders. It’s hard to figure out how to support yourself because you’re not going to end up making a lot of money from your work. And those that do better save it because it’s fickle and brutal, and what’s hot will be not in two seconds. It’s the way all markets function, and it’s just become another market.

BOLLEN: Finally, about translation. Your text pieces are often literally translated into the language of the countries in which they are being shown and installed. Do you see your works as universal messages? Since much of your work is public—wrapped around buses, on the steps of train stations, inside churches—does the history of politics or functions of the place determine what you will show?

KRUGER: Of course. Everything’s site-specific. I’ve always been sort of critical of artists who go in and do a quick read of a place and then do a work with the people there. To me, that’s exploitative in the way that some photography is exploitative. Issues my work is involved in—issues of consumerism, the place of women’s bodies—when I’m in these places, I have a reading of whether they’re issues or not, of course.

BOLLEN: Where is “Your Body Is a Battleground” not an issue?

KRUGER: I’ve not been to that place yet.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS INTERVIEW‘S EDITOR AT LARGE.