IN CONVERSATION

Awol Erizku and A$AP Ferg Have a High School Reunion

Awol Erizku (left) and A$AP Ferg at the opening of “Delirium of Agony,” photographed by Madison Voelkel/BFA.com.

When they first met decades ago at New York City’s famous High School of Art and Design, A$AP Ferg was a forward-thinking trendsetter with many interests (he was painting, styling, designing clothes, and making music) and Awol Erizku was a promising young photographer who took his studies and his art seriously. “You was the first person I knew with a video camera,” Ferg told Erizku. “You was the first person I knew with a studio.” It wasn’t before long that the two artists began collaborating: Awol shot Ferg’s first music video for “Get High,” and Ferg enlisted the artist to be the first model for his fashion brand Devoni.

Since then, the two have gone on to establish themselves as titans of the music and art worlds, respectively: Ferg, with uncompromising lyricism that waxes and wanes riotous and introspective; and Erizku, with a poignant visual vocabulary rooted in hip-hop and mediated through sculpture, photography, paintings, assemblage, and playlists. “I think it was important for both of us to find our own bearings, and find our own space, so that when it does finally happen, it feels momentous,” Erizku told Ferg when the two got together ahead of Erizku’s solo exhibition, “Delirium of Agony,” now on view at Sean Kelly, New York. “It’s not just two homies kickin it. It’s two big artists in their own fields coming together in a way that feels urgent and of its time.” Below, they reminisce on social studies class in high school—Ferg used to copy Awol’s answers—and get serious about the commodification of Black bodies in the art world, overcoming creative blocks, and, of course, Nas vs. Kendrick.

———

A$AP FERG: What’s good?

AWOL ERIZKU: I’m good man. We’re doing install on the wall. I don’t know if you can hear it?

FERG: Oh yeah, I can hear it.

ERIZKU: I feel great. I’m here with my family. My daughter is here, my wifey’s here. And we are on day one of the install for “Delirium of Agony.” I’m happy to be talking with you, man.

FERG: Likewise. I’m super proud of you.

ERIZKU: The feeling is mutual, but you know what? Because we’re so familiar with each other, I think it was important for both of us to find our own bearings, and find our own space, so that when it does finally happen—this moment for me and for you—it feels momentous. It’s not just two homies kickin’ it. It’s two big artists in their own fields coming together in a way that feels urgent and of its time.

FERG: Super urgent. Hip-hop is in such a weird place right now where it’s super saturated, and everybody’s putting their homies on. There’s a lot of noise right now. It’s not good, not bad. It’s just noise, and I think this is a perfect way to cut through it. We both went to [the High School of] Art and Design. I majored in fine arts and fashion, and I’ve always been into art. I think this is the perfect opportunity for me to show a different side of myself that people are not used to. It’s time for something new: elevated conversations that get to the bottom of who we really are.

ERIZKU: We’ve known each other through different phases. I remember when we were in high school and you were starting to do fashion. Then you went through a period of styling when I was at Cooper [Union]. I mean, you’ve always been an influencer, before an influencer was even a thing.

FERG: Word.

ERIZKU: There’s a lot of history that we could tap into, but before we even get to that, I really want to address what you’re saying about the over-saturation of media right now. I think that’s the nature of everyone having a device and everyone having a voice. I could say the same thing about art, you know what I mean? It’s not bad; it’s not good. It’s just the state that we’re in right now. I see it as being kind of a sensory overload.

FERG: Sometimes it can put you in a place where it feels paralyzing. It’s an industry at the end of the day, right? So it’s like, this is what they want. This is what’s hot. How do you deal with that in the art world? Is it like “I’m just a vessel, and this is God trying to get his message through”?

ERIZKU: You’re taking the words out of my mouth. Basically, in contemporary art in the last three to five years, there has been this boom for Black art, specifically representational art, figurative painting, the black body on canvas or whatever form it takes on. For that reason, I actually stopped making images of Black bodies. I went in the opposite direction, as I often do, not just to go against the grain, but [because] I didn’t want to be part of that commodity. When everybody was looking for that kind of representational art, and I was doing these Ramadan drawings that had a lot of conceptual and spiritual value for me, I thought, “Look, if you really care about black art, then you are gonna have to explore it from all the dimensions that it comes from.” You know what I mean? So I started making these drawings about five years ago as a way to still get my message out there without pandering to this audience that all of the sudden found this new love for Black art. But how do you deal with that in the music space?

FERG: It’s spiritual warfare because I’m always evolving. I always want to jump into different sonics. I look up to Pharrell and Timberland and Kanye when it comes down to how those guys changed the sound. Now it’s like, everybody is into Mickey D’s instead of actually cooking up Grandma’s meal, but every once in a while we get a Grandma’s meal and there’s a difference. You know, I love what Yachty did with his last album. He took a risk. Ye always takes risks. Kendrick, J. Cole, these guys take risks. Sometimes my work can take so long to make, because I care about what I’m doing: I’m putting a storyline together, going to London to get new sounds, and traveling just so I can catch vibes in different places. You kind of miss having the anthem of the summer. And I have those, but for me, it’s no longer about just the summer hit. I want people to really pay attention to the project, and I want to be able to articulate what I’m feeling through my words. I try to keep the art as pure as possible, because it is my soul that I’m bearing.

ERIZKU: You know, it’s funny you say that because I think about this in the same way that you do, where I’m like, “Yo, if I really want to make some money, I could just be doing one thing for the rest of my career.”

FERG: Exactly. You wouldn’t have done the incense drawings.

ERIZKU: Right. Until this day, I don’t think I’ve ever repeated myself. Maybe I’ll keep a format, but the content is always new. It’s always fresh. I think that’s part of what I always admired about you. I mean, how many people know about Devoni?

FERG: Not too many.

ERIZKU: I was the first owner of the first Devoni belt.

FERG: That’s a fact. Wait, hold on. You were the first model.

ERIZKU: For real. [laughs]

FERG: We shot our first pictures at your studio.

ERIZKU: Exactly! I think ultimately what you and I are interested in is advancing humanity in our own spaces. So I’ve always loved and respected that about you. And also I think you’re a unique individual: you’re not like most artists that I’ve met. You’re not full of yourself. I mean, there are people who haven’t even had a hit and are more arrogant than you.

FERG: A lot of the people who become full of themselves are the ones who never thought anything of themselves before they started.

ERIZKU: Right.

FERG: I was popular in junior high. I was broke, and I was happy. It’s only when I started making money that I started running into more problems. It’s so stupid when people start acting crazy because they think they got a little bit more. How does that make you better than somebody else?

ERIZKU: I think that’s one of the reasons why we’re still friends. You and I can go for months without seeing each other and then we’re able to cram in one year’s worth of hang out time, like the last time we were both in New York vibing off your new music.

FERG: There’s not a lot of people that I can play my music to and they actually get a deeper understanding of what I’m trying to do.

ERIZKU: I was taken back by the introspection in your new music. There are ways to give yourself that introspection without it being corny, right? I think Future’s successful in doing that, like with his song “News or Somethin.” He was talking about police brutality, but also about the complexity of being Black in America. There are levels in which people like Future and yourself operate. First you get to the hit, then you get to the deeper stuff, you get to Darold [Ferg’s real name]. And again, I have to listen to a lot of content as a DJ. I think people are making content these days, and they’re not necessarily making art. Are there any artists that influence you?

FERG: I’m super inspired by my dad. He did the Bad Boy logo for Diddy. He did the Uptown cat logo for Andre Harrell. My dad was super instrumental in how I moved, because he taught me how to hustle. He taught me that I didn’t have to wait for anybody to do anything. He instilled so much in me before he passed away. He taught me how to silkscreen myself. He also went to Art and Design.

ERIZKU: All these legends went there.

FERG: Right. Donna Karan, Marc Jacobs, Pharoahe Monch, Fabolous.

ERIZKU: Fab went there?

FERG: Fab went there. If it wasn’t for Art and Design, I wouldn’t have met you, and I probably wouldn’t have passed all my social studies tests, because I was copying off of you in class. And also, we wouldn’t have shot my first video for my song with Rocky, “Get High,” because I didn’t know anybody else with a camera. You was the first person I knew with a video camera. You was the first person I knew with a studio, bro.

ERIZKU: [Laughs] I appreciate that, man. Our neighborhoods, our family, all that really is the core of our inspiration. And I hope this younger generation isn’t missing any of that because of the over-saturation that we were discussing earlier.

FERG: Right.

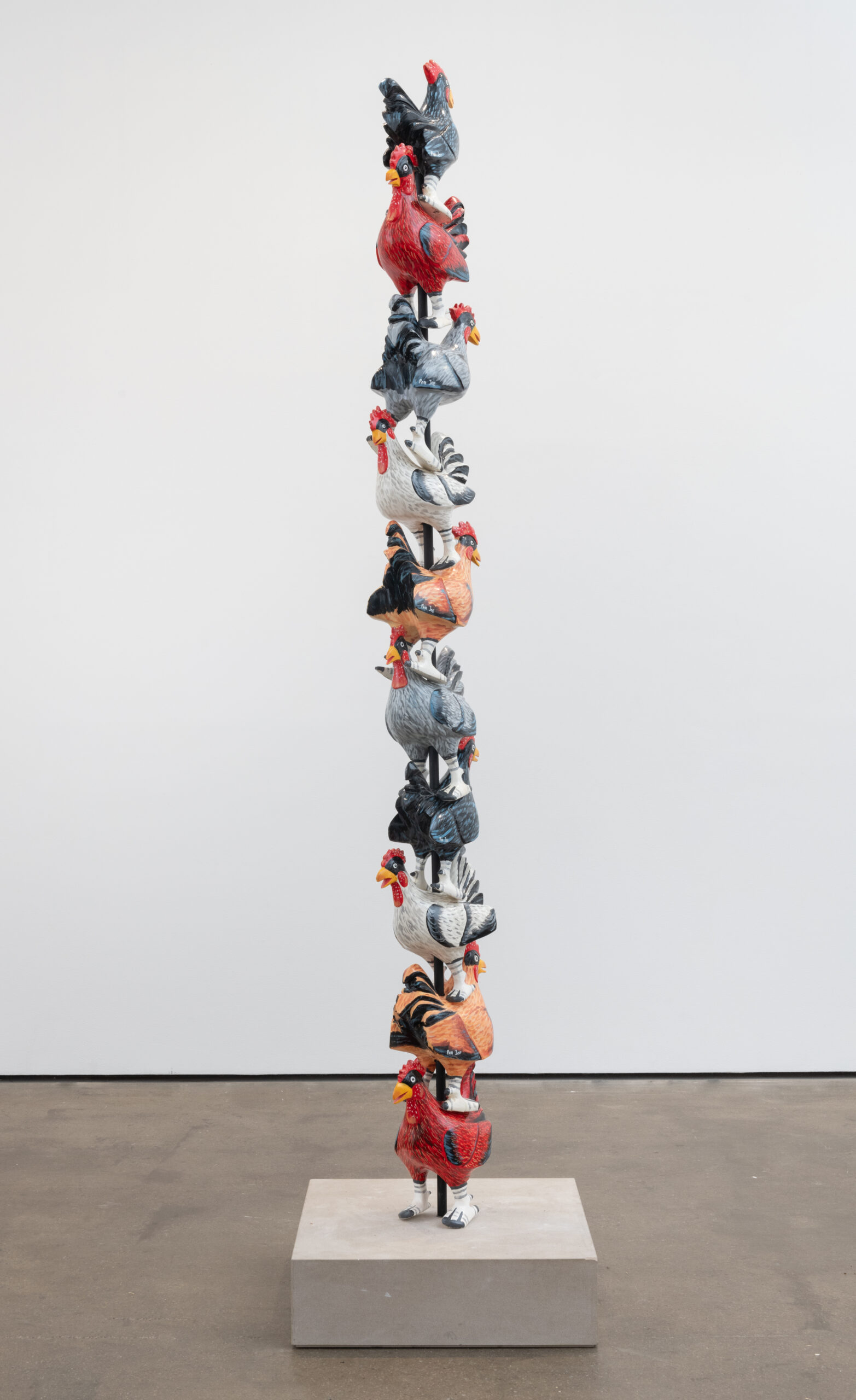

ERIZKU: I want to talk a little bit about the duality of hip hop and language. I have this sculpture, it’s called “This is Not a Hammer,” and it’s basically a hammer that I had scanned and shortened to the length of a Desert Eagle. I reprinted it in 3D in the same kind of material that they use to make guns. And I’m now representing it as my hammer, in the same way that a hammer in hip-hop isn’t really a hammer, right?

FERG: That’s fire.

ERIZKU: How do you feel about the duality of language? You’re a poet at heart, this I know.

FERG: I’m always playing with metaphors when it comes to music, like my song “Plain Jane.” A plain jane rollie is not really plain. It’s the quintessential baller watch of presidents and royalty. But at the same time, plain jane also has a double standard: you want to leave it plain because as soon as you add diamonds, it loses its value.

ERIZKU: Exactly. Michael Eric Dyson writes extensively about this in the book that he did about Jay-Z’s lyrics. I love contronyms because in the same way that you’re able to paint a visual image with words, I use that as a way to create tangible objects like sculptures. The older I get, the less I’m interested in being too directional, telling people how to read the work or how to see it. I’m just interested in bringing my experience. How do you use creative blocks in your creative process?

FERG: That’s a great question, because that was one of my fears before I made it in the music industry. I was afraid that I wasn’t gonna be able to create on demand. But all great artists go through that. There’ve been times where I could just create music and feel like, “Damn, this just slaps.” But I’m not really feeling it myself, and I’m not feeling it myself because it’s not going deeper. So I started reading this book called “The Artist’s Way.”

ERIZKU: Mm-hmm. I’m familiar with that book.

FERG: Yeah, it’s a spiritual guide for artists that gets your creativity flowing with different methods and exercises. It helped me tremendously because I had writer’s block for, like, four years even though I was still creating music. I was on the charts with Nas and Nicki Minaj, but I knew that I wanted to go deeper. I wanted to be more vulnerable. I wanted to do more things. But you have to go through those ruts in order to break yourself into a new self.

ERIZKU: Right. But also, can I just pause and acknowledge this moment. You just casually pass by it, that you had a song with Nas and Nicki Minaj. Nas was one of my biggest inspirations. I probably learned more from Nas and his music over the years than I have from any of my history teachers in school. Straight up. You can quote me on that.

FERG: Wow.

ERIZKU: No, real shit.

FERG: That’s believable. That’s how I was learning, too.

ERIZKU: I almost titled this show “Illmatic” because this is the biggest New York show that I’ve had since god knows when.

FERG: You might have to call it Trillmatic cause you got the lean in it.

ERIZKU: Come on, man. The metaphors, the versatility. I don’t think people really give him his flowers enough, because he’s educated more people than he’s given credit for. I saw a list the other day that was like, “greatest rappers of all time” and somebody ranked him under Kendrick. And I love Kendrick. He’s our peer. But in no way in hell is Kendrick better than Nas, in any shape or form.

FERG: There wouldn’t probably be a Kendrick without Nas.

FERG: What are you looking to accomplish for your next show?

ERIZKU: Man. Okay, so the idea for “Delirium of Agony” came to me when I was in Paris with my daughter, taking her to see the Louvre for the first time, and we saw the Mona Lisa. There was something about seeing it with my daughter and caring more about her reaction than seeing the piece itself. Instead of looking at the work, people turned their back to it to take selfies with it. It was really some other way of engaging with art. My statement isn’t like, “Oh, let me do a one-to-one version of these Western influences” but rather to try to subvert what they’ve been doing and how we’ve been told to look at ourselves. I’m not necessarily interested in educating people. I’m a dot-connector like you. For the lean coffin, you have to understand the culture of lean and sipping, the history of hip-hop, Lil Wayne, Future, and their contributions. And of course, we can’t forget about the South…

FERG: Pimp C. A$AP Yams.

ERIZKU: Yeah, Yams. I’ve had Yams in this film that showed at MoMA, actually. I was wearing his shirt, because he was such an inspirational figure. He was one of those OGs who connected the street with high art. Can we have an idea of when new music might be dropping?

FERG: Man, I’m literally working on the album right now. You’ve heard some of the work. We’re just basically doing all of the boring work right now, getting stuff cleared and everything. We’re winding down. I don’t have a rough estimate, but it’s been long enough as it is. I don’t want to agitate the fans even more. I just want to put it out so the fans can have it and we can move forward. So, you’ll be getting new music very soon. I’m working hard.

ERIZKU: You have a scorcher right now. I had to cue up a lot of music for my DJ set and I definitely got that one that you have with Sexyy Red. That’s a banger.

FERG: I appreciate that. There’s going to be a lot more where that comes from.

ERIZKU: I appreciate you. I look forward to catching up soon.

FERG: Yes, we got to do this again.

ERIZKU: It’s done deal.