art

At 94, Betye Saar Is Letting Intuition Lead the Way

In the annals of art history, there is a tendency to see the “found object” as a raw material best suited for the cynical, winking gestures of Dada or Pop Art. But at the age of 94, Betye Saar has spent more than a half-century creating radical, poetic, socially textured assemblages by turning mere stuff into profound masterpieces: an ironing board, advertising signs, glass bottles, throwaway items often discovered at flea markets and thrift stores, and collected in her Southern California studio. Initially inspired by Joseph Cornell’s intimate wood-box collages, Saar’s practice tackles American history and politics, often dealing directly with the loaded signifiers of racism and sexism, and turning those entrenched cultural symbols back on themselves to create powerful monuments of resistance and celebration. Saar might be most famous for transforming the racist stereotype of the Black mammy, Quaker Oats’s Aunt Jemima, into a kind of glorious liberator who won’t be hushed up or kept in the kitchen. It would be impossible to untangle Saar’s oeuvre from the Civil Rights Movement or Black feminism. And yet, her works reach beyond the vectors of politics, touching on spirituality and mysticism, astrology and the afterlife. This fall, the Morgan Library & Museum in New York is hosting an exhibition called Betye Saar: Call and Response, dedicated to Saar’s prolific output, not only displaying some of her most beloved assemblages but also her drawings and sketchbooks, the latter of which serve as essential guides to her creative output and visual feasts of their own.

Saar first met the actress CCH Pounder decades ago at a party in L.A. They became not only fast friends but fast travel companions, sharing a love of voyages ranging from Dakar to the South of France to Mexico City. This past August, Pounder paid the artist a visit to reminisce about some of the trips they’ve taken and the places they’ve yet to go.

———

BETYE SAAR: I remember when I first met you at a party at your house. I was in the corner of your living room. I was saying how much I liked the art of Frida Kahlo, and that I was going to Mexico City to see her house. And you said, “Oh, I want to go.” Do you remember that?

CCH POUNDER: Of course I remember going to Mexico City to see the Frida Kahlo house with you.

SAAR: That was our first of many trips together.

POUNDER: Actually, I think our first trip together was to Dakar in 2002. We’ve been to Mexico a few times. Once for your birthday, when Raoul [de la Sota, the artist and professor] danced with you.

SAAR: Oh, yes, that was in Cuernavaca.

POUNDER: What I remember from the trip to the Frida Kahlo house was how much you loved the color blue that was there. You were painting with so much blue at the time. It was exciting to see how inspired you were by the colors in Mexico. Mexico City itself was your “red” city.

SAAR: And a few years later, I did an installation at Roberts Projects in L.A. of an all-red room. It came from that red in Mexico. I said, “I’m going to do all red and I’m going to call it ‘Red Time.’” I was inspired a lot on that trip. I also remember all those personal letters of Frida Kahlo’s that hung on her ceiling.

POUNDER: I remember you doing sketches and drawings during that trip, all very brightly colored. And then going off to the markets where you bought those red masks.

SAAR: We made a little art exhibition in the hotel room of all the things we had bought. We had refreshments and everything!

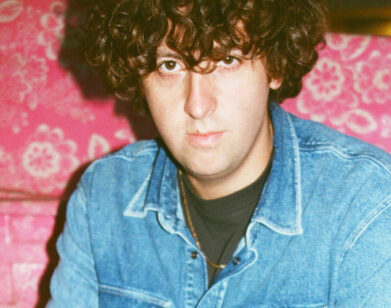

POUNDER: Looking back, [Kahlo’s Blue House] Casa Azul actually kind of reminds me of your rock garden at your home in Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles. You were so keen on the blues. Recently, you made a blue sculpture called “Woke Up This Morning, the Blues Was in My Bed,” [2019] with blue bottles over a blue neon light. Do you often start with a color in mind?

SAAR: Yes, that’s the way I often begin work on an assemblage. I start with a color or a little object, and I make a whole exhibition out of what it relates to, right down to the painting of the walls or the image I choose on the invitation.

POUNDER: You’ve often focused on specific colors, whether it’s “Blue Window of the Mystic Palms” [2018], “Black Girl’s Window” [1969], or that stark white KKK sheet next to the ironing board in your piece from 1998 [“I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break”].

SAAR: A color is the way I conceive of my shows, and I still follow that model to this day. Right now I’m doing a ladder that’s made of earth tones. It’s one of a whole number of individual pieces I’m working on. I’ll just have to see if any of them build into an exhibition.

POUNDER: Another of my favorite places we traveled together was Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the South of France. We saw the James Baldwin House and the Matisse House. There were so many beautiful colors at the Matisse house. And we wore twin pajamas and we were sharing a room. I have a photo from that trip. You’re standing, looking at a gray wall with vines that had died, and you said, “I’m going to do a piece called—”

SAAR: “Fade.” It was an idea about the process of aging, that old age isn’t just a certain state, but is a process of fading away. It’s like the gray life of old age. I wanted to do a whole exhibition on that idea. It’s because we were in Matisse’s house and he had a studio next door and vines were covering it. I thought, “The vines will swallow that building,” and I wanted my picture in front of them because it appealed to me, this idea of disappearing into the wall.

POUNDER: My biggest tickle was when you said to Angela [Robinson Witherspoon, an actress and close friend] one day, “You know, I think I’m going to make it to 100.” So you put away the idea of “Fade” and started back on brighter colors.

SAAR: [Laughs] Sometimes, when I feel good, I still think I’ll make it to 100. But next year I turn 95, and I don’t think I’m even ready for that. That’s what aging is. It’s always a surprise when it happens to you. Don’t you think?

POUNDER: Yes. Sometimes people will tell me, “Oh, Ms. Pounder, I’ve grown up watching you.” It’s like, “How is that possible?” It can’t be. But it is.

“Woke Up This Morning, the Blues Was in My Bed,” 2019.

SAAR: I’m not very far from hitting the triple digits now.

POUNDER: How do you feel about being an artist in her 95th year still making new work?

SAAR: The thing is, I don’t think about age when I’m making art. I don’t work on art if I don’t feel good. It’s not conducive. The ideas for art are always young. As soon as I have an idea about what to create, that’s the little essence of youth still in my personality, in my life. When I run out of ideas, that’s when I’ll be old.

POUNDER: So what is the essence of youth making this month?

SAAR: I’m trying to finish some sketchbooks. I started a small square one about astrological symbols—the sun and the moon and things like that. I’m still affected by that. When I was on vacation in the desert [at her daughter Tracye Saar-Cavanaugh’s Joshua Tree ranch], I woke up very early and the sun was just coming up. It was on the rim of a hill. But up in the sky was a crescent moon and a star. I said, “Those are my symbols in the sky.” And those are the symbols that I’ve always used.

POUNDER: You’ve had a lifelong fascination with astrology. Is it still part of your work today?

SAAR: I’ll read the astrological chart in the daily newspaper, but that’s just for my own amusement. I think my use of astrology has two purposes. It suggests the unknown, and then it also suggests the known by the stars and the moon, and so forth, telling your history. If you believe in those charts, their positions pertain to what your personality can do or what your life might be. I don’t really devote my consciousness to that. It’s more the symbols themselves that matter to me, like how the moon suggests peacefulness.

POUNDER: That symbolism informs a lot of your work. There is a piece at the Studio Museum in Harlem called “Indigo Mercy” [1975]. I’ve heard that in the past, visitors have left notes in the drawers.

SAAR: I had another piece that was also participatory like that, where people could leave little messages. I like the idea of the audience participating in the work.

POUNDER: There is a big rock by the water in Israel where Jesus was supposed to have waded, and there are thousands and thousands of little note prayers stuck to it.

SAAR: Yes, it’s like that, like being a part of something bigger. Sort of like touching the hem of Jesus’s gown.

POUNDER: One of your most famous works is “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” [1972]. This year, Aunt Jemima has finally been retired by Quaker. What do you think about this cultural move to stop circulating these racist images? Do you think you’ve had a part in this? I think you have.

SAAR: The reason for using her was to take a negative image and make it a positive one. I set out to take all these negative images that had been a part of Black history, and I changed them into warriors.

POUNDER: What’s really sad is that there really was an Aunt Jemima. Her name was Nancy Green. She was not a caricature, she was a philanthropist and ministry leader in Chicago. She was the first Aunt Jemima model, and then over the years, they started changing and obscuring her image into this caricature. But I remember in the end she was happy that it was her, because she put a lot of kids through school because of those flapjacks.

SAAR: Yeah, she used the money she got for good.

POUNDER: For this exhibition you have at the Morgan Library, you’re showing work that’s never previously been seen. How do you feel about that?

SAAR: I had lots of work in my cupboard that I haven’t shown before, from the ’70s all the way up to the present. They just haven’t fit the theme of a show. I really like to stick to a theme, that could be derogatory images or political issues or women or something like that. I feel more comfortable working that way.

POUNDER: You can read one of your assemblages in so many different ways. And to go back to color, you can have the color white in the KKK sheet, and then that same year make a piece out of a white christening dress that you can imagine will be worn for a beautiful little orphan girl [“Loss of Innocence,” 1998]. Those are two such different connotations of white. How do you conjure up these works?

SAAR: Well, my mother told me I was very psychic as a child. I could tell her if my father missed the bus or if something else happened. Eventually, I lost that ability. I’m no longer psychic but I’m very intuitive about what colors to use, what materials to buy, what people to be friends with. The intuition is a strong element in my life and that comes from a larger psychic power of knowing things unknown before they happen. I think, when I create, I use that intuitive power.

POUNDER: Do you tend to work on multiple pieces at once?

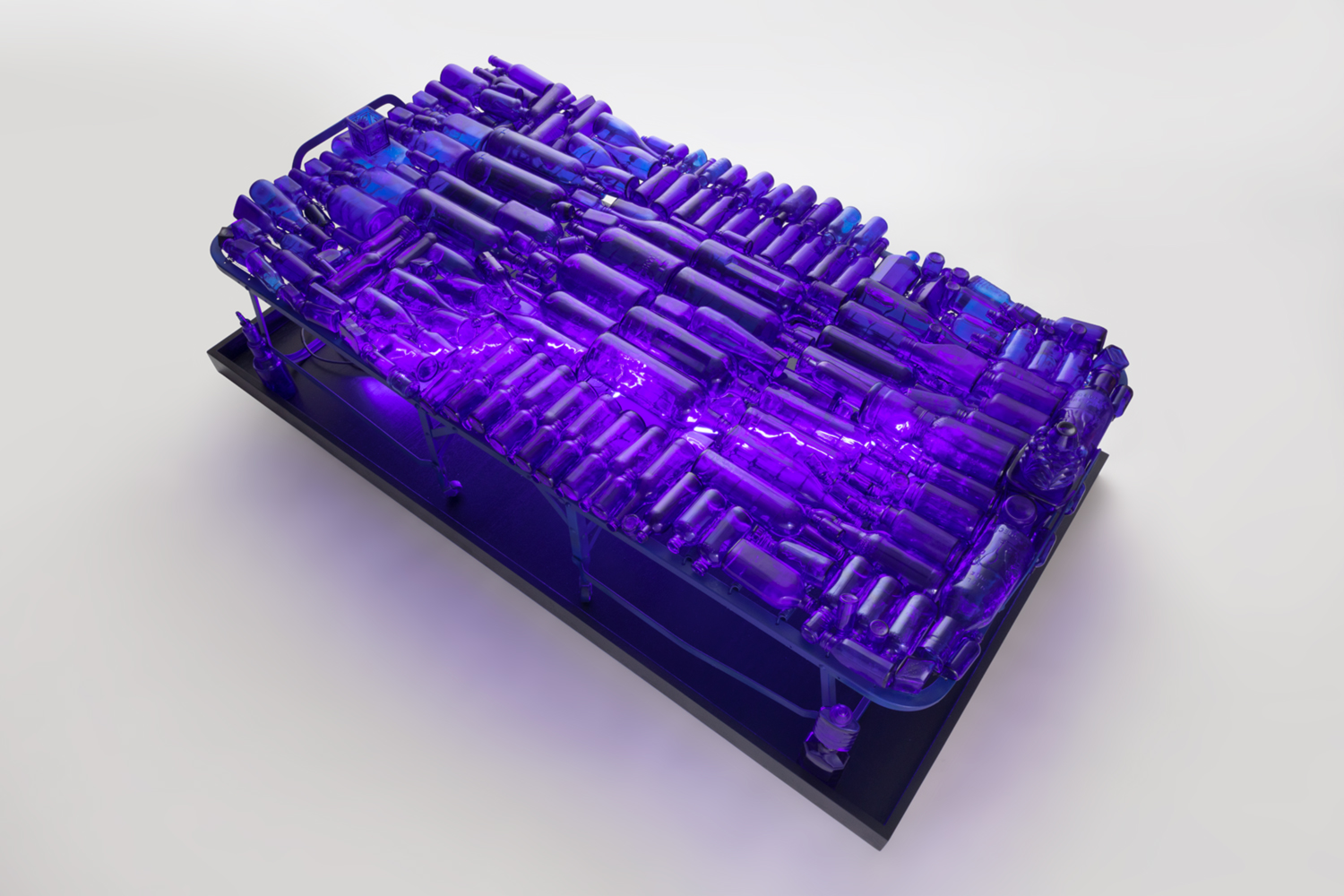

SAAR: Well, I have the ladder I’m working on in my studio. In my garage, I have a Bottle Bush—a structure I make from blue bottles. The works are in different places in my studio, but it’s always organized by color or some other element. That seems to be the restriction that I set on myself to do art. I need to do that. I can think, “I’m going to start here on a little painting,” but sooner or later all my restrictions come into it. I want to use this color, not that color; I want this image, not that one. It’s a natural part of creating and a natural part of my personality to keep me from going crazy.

POUNDER: It gives you a sense of discipline and yet it allows you to create.

SAAR: Yes, I need those limits. Sometimes I look at a piece of abstract art with color and movement, and think, “I wish I could do something like that.” But for me, a more formal situation will gradually come out of it. So here we are.

POUNDER: If you hadn’t become a visual artist, what else do you think you would have been on this earth?

SAAR: A writer of poetry.

———

“The Divine Face,” 1971.

———

Artwork: Courtesy of Betye Saar and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles