Asif Farooq’s Paper Plane

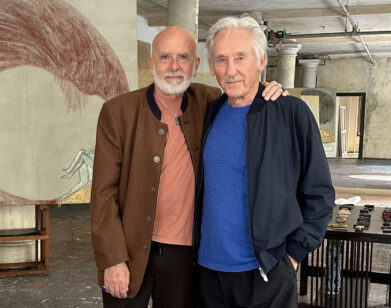

ASIF FAROOQ IN MIAMI, OCTOBER 2015. PHOTOS: ALLEN HENSON.

Artist Asif Farooq is making a paper airplane. It is not the sort you’d expect to find gliding through a classroom, but a 102 percent-to-scale model of a Soviet-era supersonic jet fighter engineered entirely from paper and glue. The project is scaled at 102 percent simply because Farooq is quite a bit taller than the average Russian pilot.

When Farooq finishes construction, the plane will be a 4,000-pound paper sculpture, fully representational of a MiG-21 inside and out. First unveiled in 1956 in the Soviet Union, the MiG-21 became the preferred fighter of the Eastern Bloc throughout and beyond the Cold War. One might say it’s akin to the AK-47 of warplanes.

Farooq’s MiG-21, which will be unveiled during Art Basel Miami Beach next week, is a series of both engineering and fine art marvels: how does construct a two-ton paper sculpture that remains standing on paper landing gear? How does one force strips of paper to stay at the 45-degree angle necessary for paper turbine blades? How does one deftly chisel paper to form control panels teeming with dials and gauges, as well as thousands of hardware connectors, including rivets, dowels, bolts, and screws? In a charming, yet mischievous way, the 36-year-old artist likes to say the plane is a work of forgery, a parlor trick or sleight of hand. But while it seems unbelievable—perhaps even magical—it’s certainly no deception.

A project of this scale, on both macro and micro levels, requires a close-knit crew and a studio-cum-hangar that often gets likened to a certain well-known chocolate factory. Shop Superintendent Erica Mohan is learning how to operate a multitude of shop tools that, if not donated, are built on-site. (Resting on the bandsaw is an image of a mutilated hand, to remind everyone of the respect needed for things that can seriously injure or even kill.) Shop Foreman Angel Osorio conducts much of the construction (and he also force feeds Farooq lunches that he prepares at home the night before). Sometimes they spar and practice Jeet Kun Do with each other. The studio is often filled with laughter, the hush of awed visitors, the blare of Michael Jackson on the stereo.

“How?” is the most asked question in Farooq’s studio, usually followed immediately by “Why?” The answer is never simple, but it always has something to do with the fact that this Miami-born-and-raised son of Pakistani parents is deeply fascinated by art—and more importantly, by the actual world outside of the art world. We met the artist at his studio in Miami to learn more about the process and his background.

ROB GOYANES: You started drawing when you were 5 years old, right?

ASIF FAROOQ: Before that. I was drawing on the walls and I would eat my mom’s oil paints—she was a painter. She would hide them at the top of the closet. It was like when parents put things there and then the kid piles up all these different chairs into a creaky ladder and climb it to get the stuff they’re not supposed to have. So whenever my parents would have a babysitter over I would get into her art supplies.

GOYANES: And ingest them.

FAROOQ: Yes.

GOYANES: When did you first become enamored with art?

FAROOQ: Michelangelo’s preparatory drawings.

GOYANES: What’s your earliest memory of making art?

FAROOQ: I was always kind of compulsively making weird little things with my hands. My mom would say, “You were always sitting there by yourself, making stuff.” My dad was an engineer, so I was also getting into my dad’s drafting supplies.

GOYANES: Were you interested in engineering at an early age?

FAROOQ: No, I was interested in his tools. He had drafting tables, sliding rulers, parallel rulers, and metric rulers. I was intrigued by all the possibilities. When I was young, it was always my lack of a technical ability that kept me from being able to achieve whatever very specific goal I had. But at times, when I wasn’t so self-conscious, I would occasionally make something really good. I made a perfect portrait of my father when I was maybe eight or nine with a paper dinner plate and pen. I remember he kept that in his office for years and years. Then one day we had a fight and I went in there and tore it off the wall and shredded it, which of course, wasn’t the mature thing to do. So what he did was take all the pieces and tape them back together.

GOYANES: Did he teach you how to build things?

FAROOQ: He taught me how to build things that worked. He got me a book called Why Buildings Stand Up. It talks about form resistant structures, post-tensioning, dead loads, and live loads. When I was about seven or eight, because I was always making stuff, he got me a hacksaw and a block of aluminum. I spent all summer making a three-inch cut in the aluminum, because I didn’t know that I needed to lubricate the cut. That was a good way to keep a bizarre child busy.

GOYANES: You started welding at a young age too, right?

FAROOQ: At 13 I started going to see this guy named Ken Thompkins Jr. at a place called The Metal Man. I cold-called everybody in the Yellow Pages and he answered the phone. He was a crazy old white dude and he was like “Son, how old are you?” and I’m like, “13, mister!” So I go over there, and he tells me the most crazy and beautiful thing in the world. He says, “Well, you know, my father and I were a killing team in Vietnam. My father flew a 707 low over the treetops, picking up the SAM [surface-to-air missiles] batteries on radar. I would come in behind and mow ’em down with a chain gun.”

GOYANES: You painted the office of your studio the same shade as a psych ward. Why?

FAROOQ: I was institutionalized on and off since I was 11 years old. I was bad into drugs; I didn’t have a positive or clear self-conception, and the drugs helped me slow down and make sense of my life. It was one of those things where you’re young and scared and you don’t know anything. You know you don’t want to be some conformist douchebag, but you don’t know how else to survive. It seems like everyone survives that way. And do you even want to survive? The answer to that, for me, was no.

GOYANES: The answer has changed since then. Five years ago you got clean, and it was around then that you realized you wanted to build the plane, right?

FAROOQ: Yeah. Dad died in April 2009, and I was in the hospital a couple months later in July. I had had a heart infection and a pulmonary embolism. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to make a Su-7 or a MiG-21.

GOYANES: Why the MiG-21?

FAROOQ: For its relevance in the larger Cold War story. The Russians wanted a high-speed interceptor to come up and quickly hit thermonuclear-armed NATO bombers. When you look up images of the plane you see them abandoned on the side of the road or in people’s backyards. They epitomize the Soviet design aesthetic and have had a longer production run than any other aircraft. They were simple to make, repair, and fly. It’s a plane that a lot people don’t give a shit about—you can buy a real MiG-21 for less than it’s costing me to build one out of paper. There are 25 of them flying in Florida alone.

GOYANES: What fascinates you most about the Cold War?

FAROOQ: Rather than a single specific thing, I think it’s important to understand what happened from an interrelated, multifaceted perspective. It relates heavily to our current geopolitical reality. Also, it’s important to understand that it didn’t come from nowhere, that the Cold War was a product of the Holy Roman Empire, of colonialism, and the shifting resource and labor needs of late 19th century world powers.

GOYANES: Is there a political stance with the work?

FAROOQ: I’m not trying to relay a personal political opinion, such as “USA: Good, Commies: Bad,” or “Commies: Good, USA: Bad.” Both of those are far too simplistic. You want to know the real reason I’m building the airplane? I’m manufacturing my future good memories. I want to know that I built a MiG-21 with my bare hands.

GOYANES: You have deep connections to military veterans. Your staff photographer Allen [Henson] is a veteran of the Iraq War. I’m curious about these relationships.

FAROOQ: I think a lot of guys that serve in foreign wars come back to a country they don’t recognize or don’t relate to anymore. And I myself have always been an outsider. Most people in America get their news from electronic media, not from living it. The qualities I look for in my friends and colleagues are intelligence, integrity, and honesty. Allen is a perfect example.

GOYANES: Who else has contributed to the project?

FAROOQ: AK Strain is the project’s costume designer. She is designing and tailoring uniforms for the staff and personnel on this project. This is an important component of the project for verisimilitude and authenticity.

GOYANES: You’re not currently represented by a gallery and decided to take on this project with the help of your agent Nick Cindric. What are positives and negatives to this approach?

FAROOQ: Nick and I have a special relationship. I’m the only artist he currently represents; he works primarily on the secondary market. Working with galleries, in my experience, limits you to what they are able to get behind. These last couple years I’ve built a company and my own team to expand those boundaries. I don’t want to live like it’s my practice life; there’s no second go.

GOYANES: What’s your dream for the plane? Where would you like to see it once it’s done?

FAROOQ: Sometimes, I think I’ll take it out to Tushino, the airfield in Moscow where it was first unveiled, and have it disintegrate out on the tarmac, even though it’s been built to last a long time if it’s taken care of. I think it would be nice to watch it slowly decompose, like the fate of so many Soviet aircrafts. Or maybe it’ll go to a nice museum where my nephews could visit it.

GOYANES: What are some other pieces that you’re working on?

FAROOQ: Another project I’m working on is a geo-synchronous micro-satellite, which will have an iPod playing Metallica’s Kill ‘Em All on continuous loop over Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.

ROB GOYANES IS A WRITER BASED IN MIAMI WHO IS WORKING ON AN ‘OWNER’S MANUAL’ FOR FAROOQ’S MIG-21.