A Weighty Issue

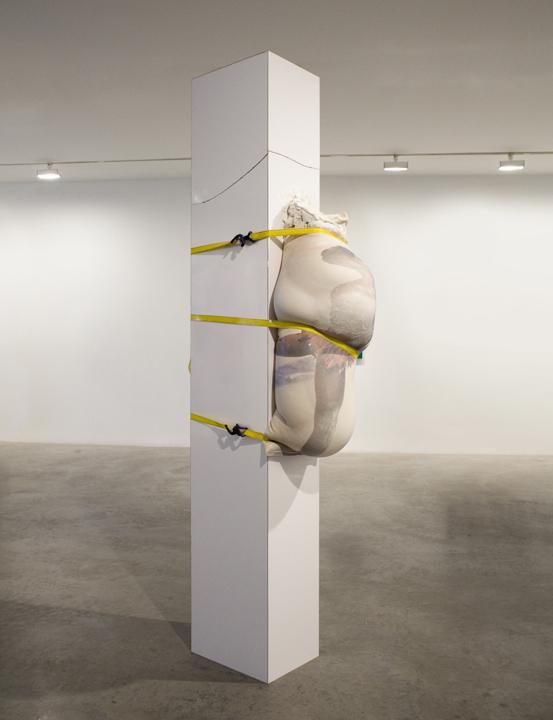

At 72 square feet in an industrial Meatpacking District foyer, 55 Gansevoort is a gallery as compact as they come. Earlier shows have been accommodatingly small-scale, but the latest installation makes past works look downright dainty. Devised by artist Ashley Carter, Tilt is a claustrophobia-inducing hunk of white wall protruding from the gallery’s actual white wall. Occupying most of the space, the daunting, minimalist sculpture threatens to crush viewers as it appears supported by a single strap.

For Carter, who graduated with an MFA from Columbia in 2013, the proverbial white wall is a weighty topic indeed. Known for her large-scale drywall sculptures, she couldn’t resist strategically packing one into 55 Gansevoort. “This is begging to be filled,” she thought when she first visited the space with owner Ellie Rines.

Surrounded by posh retail stores and nightclubs, any of which could fit the gallery many times over, Tilt also comments on the increasingly exclusive nature of real estate: As artists including Carter are pushed farther into Brooklyn, or out of New York all together, the piece likewise invades viewers’ space. “The white wall is a support system for artists,” explains Carter. “We need the economic system; we need the space; we need the gallery. It’s this paradox of needing space, but it’s intrusive.” While a gallery’s white walls economically and physically sustain art, the cost of space–partly inflated by the people who would buy expensive art–impinges on artists’ ability to survive and work in the city. “There’s no real estate for artists, there’s no space,” says Carter. “I worry about New York.”

It’s hard enough for artists in general. But as a female artist, Carter cringes as she recalls when someone explained why women’s art isn’t as sellable, or hears feedback like “‘I don’t see any gender in your work.’ It always pisses me off, because how come men don’t have to address their gender? Why do I always get asked these questions?” she says. She’s amused that her style is often seen as conventionally masculine–a satisfying subversion. “I relate to a macho building nature–I like building materials. I think there is a part of a woman making macho art that is very funny.”

Another element of Tilt Carter describes has to do with the ephemerality of the sculpture, despite its imposing solidity. “I build these massive things, and then utterly have to destroy them [to remove them from the space], which is exactly what I’m going to do at 55 Gansevoort,” she describes. “Then they only exist in photos. This speaks to the dimensionality of something you have to experience in person with your body–rather than something hanging on a wall.”

Over the phone, Carter talks in long sentences, hopping from idea to idea. Yet even with many well-thought out concepts, she welcomes viewers’ interpretations. “The thing about art is that everyone has his or her own relationship to it,” she says. At 55 Gansevoort, where shows are on view 24/7, the wall will do the talking.

TILT WILL BE ON VIEW AT 55 GANSEVOORT THROUGH JULY 15.