Artists at Work: Artie Vierkant

It’s a tangled world wide web out there, and artist Artie Vierkant has always been always ahead of the curve in conceding the impossibility of controlling images and information jumbled therein. His 2010 essay “The Image Object Post-Internet,” which he wrote while in graduate school, dismantles the notion that art–or anything, really–can have a true “original” in a digitally mediated society. Authorship is “ubiquitous;” images dominate in a language all their own.

The text became the outline for “Image Objects,” a conceptual series that shortly after launched Vierkant’s career and made him both famous and a bit notorious for his online guile. On a material level, the series is composed of works with flat surfaces that appear to have multiple translucent colored layers, and the first sculptural version is currently on view near City Hall Park in Manhattan. He designs them to have the illusion of depth, however, viewers cannot gauge this unless they witness the smooth surfaces of the works in person. Vierkant pushes this complication further by manipulating installation views he is in control of distributing (e.g. on his and his galleries’ websites) with basic Photoshop tools, and he may change the versions on his website over time. With these variations existing in different states apparently free of temporality, the idea of maintaining an “original” copy proves fruitless.

In 2013, Vierkant began examining laws around the authorship of intellectual property in his series “Exploits.” The first show, “US 6318569 B1, US 8118919 B1; (Exploits),” featured two inventions Vierkant licensed from their patent holders and incorporated into works. A later show at Higher Pictures gallery in New York aimed to merge “Exploits” and “Image Objects,” but fell through when Polaroid, the corporation Vierkant was working with, failed to grant usage rights. Although the works were on view at the gallery for a month, the company name is now written as “[redacted]” on his and Higher Pictures’s website, and in installation views the artwork is methodically blurred out, instead of cheekily distorted as per Vierkant’s typical style.

This month, he has two separate solo shows opening with the single gallery entity Mesler/Feuer and Feuer/Mesler. For one, his fourth “Image Objects” show since the series’ debut at Reference Gallery in 2010, Vierkant is taking the installation view photographs from past shows and phasing them into the physical works. The other show, “AN ON MO SA NS,” continues his consideration of intellectual property, this time broaching the legalities of patented genetic material. Clearly not one to shy away from a challenge, he has taken on the agro-giant Monsanto, obtaining GMO seeds which he is “sowing” into resin canvases.

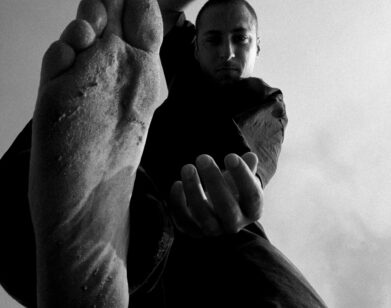

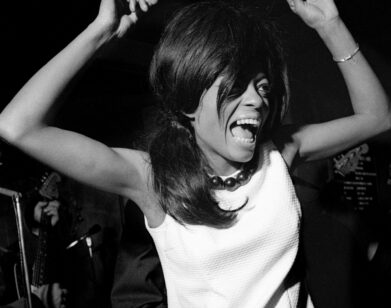

We met Vierkant at his studio in Red Hook, where we photographed a raw “Image Object” on the wall that he amended for us.

RACHEL SMALL: Can you tell me about the two separate shows coming up at Feuer/Mesler and Mesler/Feuer?

ARTIE VIERKANT: The one at Mesler/Feuer is a show of a series of “Image Objects,” which I’ve been working on since 2011. The other show at Feuer/Mesler is an exhibition of a new series of work, which deals with intellectual property, an extension of [projects] I have been working on since 2013. For that, I have secured a large-ish allotment of agricultural farm seeds, which are patented and modified GMO seed from Monsanto.

SMALL: This breaks from the initial series, “Exploits,” correct?

VIREKANT: “Exploits” was a series where I was finding different [patented] pieces to work with, and properly licensing it from the inventor or current owner in order to produce work derivative of that intellectual property. I was interested in moving on to something with intellectual property when [it became a] big news story. It’s often because the corporation has been doing something, like Monsanto.

SMALL: What inspired that?

VIERKANT: A couple of years ago I reached out to Polaroid. I wanted to use their logos and trademarks to produce work. I was in contact with the head of licensing for four or five months and was assured it was going to work out. So I went ahead and produced [the work]. Then they stopped responding to my emails and it was terrible. So I had this interesting situation where I basically had this exhibition of works, which were physically complete but conceptually incomplete. That was the first time that I tried to deal directly with a corporation.

Since, I have been trying to get my hands on agricultural seeds. I am not a farm business and in order to get Monsanto seed, you have to sign a licensing agreement. It says that the only thing that you will do is plant the seeds for one season. Don’t save any seeds. Don’t resell the seeds. Don’t send the seeds anywhere outside of the United States, which is going to be difficult considering that my work goes around.

Basically I wanted to bring us into the realm of the organic. One of the reasons that I have been making work with intellectual property is because essentially I feel that it’s one of the most important tenets of the project of modernity itself. That is, questions of what is authorship? What is ownership? What are all of these things? Intellectual property is obviously a thing that is a practical, in a legal sense. It ties all of those things together. We also have a philosophical understanding of what it is. It is interesting to see how those things are related and the ways in which so much of modern art history is in response to those questions.

SMALL: So are you sowing the seeds into your work?

VIERKANT: I’m grinding up the soybean seeds, and they are planted in fields of resin. Technically, within the bounds of the contract that I am interested in working with, they are supposed to be sown. Monsanto contracts appear [to] worry that people are going to get the genetic material if the seeds are resold in any way and figure out elements of their production process, or something like that, and exploit that. So the grinding is meant to essentially decimate them and make them so they’re not usable as farm seed. Then they are sown within the fields of resin.

SMALL: But by taking what’s theirs and putting it in one of your paintings, doesn’t it become your intellectual property?

VIERKANT: No. That would be appropriating. That’s important to me with all of this. I think “licensed” is the best descriptor because I have license to use it.

SMALL: Were you looking to push the boundaries of the contract?

VIERKANT: Yeah, a little bit. Monsanto is famously litigious. I suppose I could be sued. These pieces have been very explicitly set up so that while, yes, these are provocative materials and have very specific restrictions, these constitute as interpretations of what is outlined in the contract.

SMALL: So what about the other show?

VIERKANT: At Mesler/Feuer I am doing a show of “Image Objects.” This is the first time that I will have taken installation views of past work and incorporated them into “Image Objects,” which is something that I have heard people assumed I’ve been doing all along. People have assumed I make one work, photograph it, alter it, and then that becomes the next work, but it’s not an ongoing chain like that and the process is never so linear.

The installation views are important to me for the project, because when I am making these “Image Object” compositions, ultimately the composition could become anything. By altering the photographs of those objects, the installation views can continue an aesthetic evolution. So when you are viewing them in a mediated form, the compositions might not look the same as the first time, and probably don’t look much like the object you saw in physical form at all. It touches on the object-image divide, the way that we view and interact with images and objects. If you see a representational image of something it’s like you’ve seen an object in person, in some ways. By intervening in that space, the object—as a mediated experience—becomes non-mediated, and therefore a work in its own right. And after a certain amount of time, these installation views develop their own language. At this point, it just made sense to bring the aesthetic language of those installation views back into the fabricated work and further complicate them aesthetically and pictorially.

SMALL: So someone who has seen it in person and someone who has seen it only online might have different ideas of what the real thing looks like.

VIERKANT: That’s true. I fully understand the way in which it is confusing and I think it’s intentionally made to be so. Part of the idea is that if you’re looking thorough these and something seems unreal or surreal, you stop and notice that this isn’t maybe what it appears to be. It’s simple retouching tools used to intentionally disrupt the image.

SMALL: Have you thought how multiple versions of the same installation shot would be floating around on the Internet?

VIERKANT: That hasn’t happened exactly… When I was young museums were still enforcing rules against photography. They wanted to stop the spread of poor images. There was the worry that if someone took a photo of an object that it denigrates the value of the object. Except we know now that it doesn’t operate like that. The more images you see of something, the more powerful it is. Or if not powerful, the more you will recognize something, and it will have the possibility of being powerful.

FOR MORE ON ARTIE VIERKANT, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.