ICON

Artist Penny Slinger Left the Male Gaze in the 70s

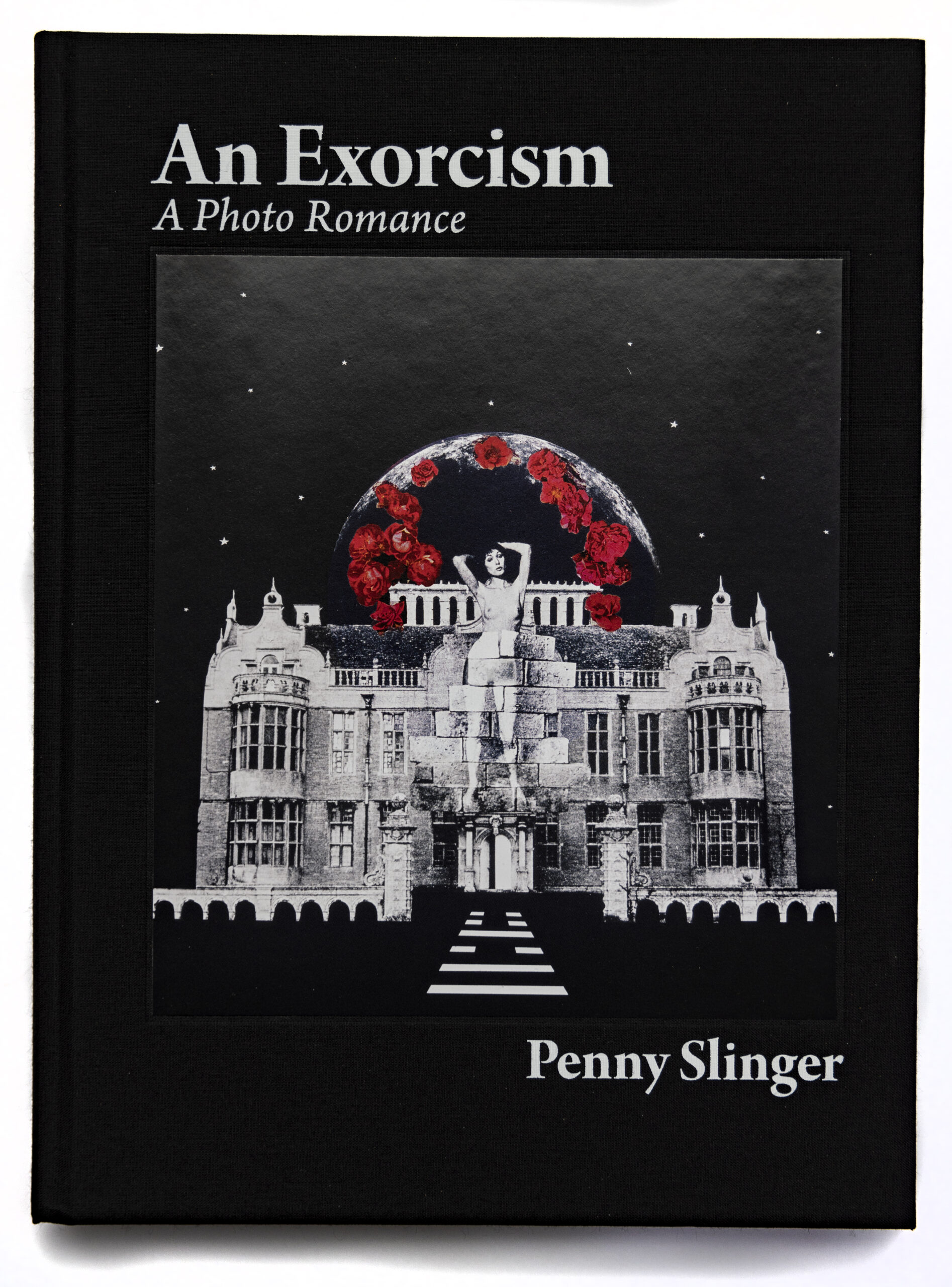

Nearly 50 years after it was first published, a new deluxe edition of British artist Penny Slinger’s An Exorcism: A Photo Romance was released in May. Based in Los Angeles, Slinger continues to make and exhibit art that explores women, the esoteric, sexuality and gothic iconography. Back in 1977, the book arrived as feminism was burgeoning in the US. But the work, done in Slinger’s trademark photo collage style, one that seems kitschier now than it might have at the time, has only gained in relevance and power. Slinger speaks to a truth women still feel, the ways “many people are never able to fulfill their own truly creative potential because of their entrapment by social conventions, spirits of the past and other people’s ideas of them,” as she explains.

The new, deluxe edition has “the whole cycle” of images, some of which were not included in the original 1977 book. At the time, Slinger had just discovered the photo collage approach of the artist Max Ernst. Using his surrealist style as a kind of blueprint, and herself as her own muse, allowed her to “create new worlds or new realities using this language.”

Just in time for the reedition, and after some time away from the art world establishment, it’s no surprise that international museums, including the Tate Britain, have begun to reconsider Slinger’s legacy. And Exorcism: Inside Out, an immersive gallery show of Slinger’s work, will be on view at Richard Saltoun in Mayfair through September 7. Even Maria Grazia Chiuri, creative director for Dior, invited Slinger and her creative partner Dhiren Dasu to creatively reimagine 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris for the House’s 2019 haute couture show before the building was renovated. Naturally, Slinger plastered the surfaces of the interior with digital collages and 3D sculptures, and contributed a haute couture look of her own: a wearable, gold-leafed version of the building itself. To mark the release of An Exorcism, Slinger joined me last month to discuss censorship, the divine feminine, and a career that has defied convention and predictability.

———

CAT WOODS: You’re based in California. Can you tell me about that choice to live and work there?

PENNY SLINGER: Well, I have been out of England, where I was born and raised, for quite a long time now because I’ve traveled quite a bit. The first time I went over to America was to work on a book project in the late ’70s. These things have often been work-related. I lived over in the New York area, and then we moved to the Caribbean and I was there for 15 years. Then came to Northern California and was there for 23 years in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains. And then six years ago, I moved here to L.A., and it was rather coupled with coming back into the art world. I was not really on the radar anymore of the fine art world. But I got a chance back in 2009 to show in a couple of major exhibitions: one at the Tate in St. Ives called The Dark Monarch: Magic and Modernity and British Art, and the other one was this wonderful exhibition of women’s surrealists that was held in Manchester and curated entirely by women. That really brought me back in connection with the fine art world, and I didn’t realize I’d disappeared just because I wasn’t there. I felt that I needed to be more visible again, which is why I thought being in a city was important. Now I’m in this wonderful building, which is the old Federal Reserve, and I have my art in a vault here.

WOODS: Oh, wow.

SLINGER: The art and archives are in the vault of the old Federal Reserve. So I think that’s rather perfect, and we have a nice community of creative people here.

WOODS: On your website, you write that you “make artworks to bring the inside out and the outside in.” What does that mean to you?

SLINGER: Since I was young, I realized that the feminine presence was very strong in art, but usually as the muse and as the person pictured rather than the person doing the picturing. So I thought, I want to shift this paradigm and maybe even be in two places at once, as both the beheld and the beholder. And in doing that, I felt that what I could bring as a woman, and especially as someone using myself as my own muse, was more access to what was happening inside. Not just the surfaces, not just what someone looks like, but what’s going on inside them, what their dreams and their fantasies are. I wanted, right from the start, to really excavate and to pull up from the unconscious and subconscious realms, and later the super-conscious realms, all this information and imagery about what’s really going on and who we really are. That was my modus operandi, to shake up some of the established ways that we see women and that women are seen.

WOODS: In a way, it’s bittersweet that An Exorcism is still so incredibly relevant decades after you made it. I can’t help but think, wouldn’t it be fantastic if women today didn’t have to feel so repressed and controlled still? Does that occur to you as you are bringing this book back so many decades after you made it?

SLINGER: Well, I’ve always been interested not just in making some timely comment, but in the more timeless aspects of things, things that are archetypal and therefore don’t have a shelf life. They don’t become outdated because they’re essential. It’s like looking at the hero’s myth or, in this case, the heroine’s myth. So what I did with An Exorcism, and it took me a good seven years of working on it, was a real guide into the essential questions that we come into life with when we start looking at ourselves: Who am I? Where do I come from? Where am I going? And in that process, it was a time when I was absolutely disintegrating because my primary relationship with my man had fallen apart, and my relationship with the women in this women’s theater group had all fallen apart, and I thought, “How do I put myself back together, and why am I feeling this way, and how can I be this damaged by what happens to me?” So I went on this detective journey to try and find out what was behind the door of all these rooms of myself and pull the skeletons out of the cupboards and bring them out into the light of day so that they weren’t spooky and frightening anymore. Because when something holds you in fear, then you are not free. And I’m all about liberation, particularly of the feminine, because she’s been so repressed for so long. So that was really the journey, and I think that journey is relevant at any time and in any place because we all really need to go through that process of individuation, of claiming our right to be ourselves. I wanted to be able to chart maps of how one can have that kind of self-revelation, and I use the references to all that gothic melodrama that’s deeply embedded in British culture. That was very evocative for me because I thought, “I can play out all the aspects of myself in my father’s house but then, in the end, come out and have the key myself and not be locked out from my true self anymore.” So that’s the path, and I put up a lot of blueprints and signposts so that others on their own journeys of self-realization would know that they weren’t alone in the darkness and there was a thread that they could follow.

WOODS: It definitely spoke to me, and that’s why I’m so thrilled that we’re talking now. The spirit of it is very alive. This new edition came out via Fulgur Press in May and has additional images that you’d kept in an archive. Can you tell me about these?

SLINGER: The original body of work, which spanned this seven year period, had a lot more images than what went into the original 1977 publication. After the 1977 version came out, there was another publisher who came to me and wanted me to do what we call the “expanded deluxe edition,” which would have all my words included and have the whole cycle of imagery. But then I had this other book, Mountain Ecstasy, which was also collages and poetry, and they decided to do that one first. That one was coming in from Holland. I was in the UK, but the printer and the publisher was in Holland and thousands of copies of that book were seized and burned by British customs. So, understandably enough, they then put off doing the publication of the exorcism book. So I went to Holland and I grabbed all the materials and I came back with it. I’ve sat on that for the last nearly 50 years and now, its time has come.

WOODS: I was going to ask about the book burning, but before I get there, I want to come back to one of the images that I really love from An Exorcism, which is “Call of the Wild.”

SLINGER: With that one, we’re looking again at that dialogue between the inner and outer beast. We all have these untamed wild creatures inside us that are generally subdued by cultural requirements and we don’t let them out. So for me, “Call of the Wild” was very much that wildness that we have in our souls wanting to be expressed. So all these big creatures for their fangs and their talons are crowding around the windows, and she is in fact embodying that energy, and a call goes out and resonates with all those creatures of the natural world that we try and separate ourselves from. But we’re actually part and parcel of all of it.

WOODS: You can’t see, but I’m grinning ear to ear. I love that idea. Your signature style is photo collage, and using your own body as a model and a muse. Was that an unusual thing to be doing in the late ’60s? Do you recall how you felt about seeing photos of yourself in those early stages?

SLINGER: Yes, it was an absolute decision because when I was doing my thesis, I did a lot of research to decide who I was going to do my thesis on, and that’s when I discovered the collage books of Max Ernst. Really, it opened up surrealism for me in a way that I hadn’t in fact accessed before. This was a language, and you could create new worlds or new realities using this language, and how fantastic? Max Ernst was creating all these dream scenarios and archetypes of mythic weaves that I just felt passionately drawn to and I wanted to make art that was inspired by him, because I think that’s the real way that you pay tribute. So I made an animated film of Une Semaine de Bonte, Max Ernst’s collage book I was studying, and I also made my own first book. I decided to use photographic collage rather than use the old engravings because I wanted to make it more mine and a little more timely. Photography is such a tool of our age and of course, it’s developed so much since those days. But at that time, it was a more rarefied field. I wanted also to use those tools that I found in surrealism to express the feminine psyche, because looking over the history of art, I saw women everywhere, and naked women everywhere. The muse was so present, but all the time viewed through the lens of the male artists. That felt to me like a challenge. Like a red flag to this little bull, I came out with my horns charging saying, “I’m going to do something about this and I want to be my own muse.” It’s a very interesting exercise, too, to put yourself in two places at once as both subject and object. It is dissociative, but it allows for a reassociation on another kind of level. Once you are able to view yourself as a work of art, you are actually going beyond your ego and using yourself as a vehicle to express something that you have inside.

WOODS: Let’s go back now to that event you mentioned. Your 1978 book, Mountain Ecstasy, was printed in the Netherlands and thousands of copies were burnt by British customs. Do you remember how you felt at the time?

SLINGER: I wasn’t living in the country at the time, so I couldn’t really go and deal with it head on and go to the courts and battle for it or anything like that. I was slightly removed from that level of the drama. But it did make me think, “My goodness, has nothing changed? Are we still medieval?” I mean, this is such a medieval act, burning books and not wanting things to be disseminated. The main thing that came to my mind was, “My goodness, they can’t tell the difference between pornography and its alchemy,” because I used a lot of erotic imagery that I gathered from all over the world, but it was transmuted and transformed into something that wasn’t some kind of base fornication. It was actually this beautiful celebration of the erotic nature and everything, and it was set in the mountains and everything vibrated with this ecstatic energy. That was the gift, but they couldn’t see it. And I thought, “How sad.”

WOODS: Let me ask then, when did you begin to have an interest in how the sacred and the divine are tied to femininity and sexual energy?

SLINGER: I think it was something that I came in with. I was rather precocious when I was young. The first drawing I did had my mother and father naked, with all their sexual organs. And probably being a Libra right on the cusp of Scorpio, I had this male-female balance, but also this very strong sexual energy. And this was one of the things I saw with the women’s liberation movement; in the early days, particularly, they were not keen on being sexy because they wanted to have their rights and they wanted to be therefore accepted on the same level with men. I felt that all our sensuality and all these things that we have a right to were getting thrown out of the window with the desire for equality. I thought what we need to do is just turn these tables and become the subject again of our own sexuality, to own it and claim it. And when I was young, I was always interested in kind of mystical things. As a young woman, the split between the spirit and the flesh just didn’t feel right to me. And then when I discovered the teachings of tantra, it was such a permission. It was, like, “Oh my goodness, there is actually a school of thought with a long tradition and a rich culture behind it that says one’s sensuality, one’s sexuality, one’s material being, can be part of your spiritual path.” And not just can be, it is. And let’s celebrate that and honor that and make that bridge between the sacred and what we call the profane. I think this is the gift of the divine feminine. This is what we need to awaken to collectively, because it’s about honoring all of nature as a manifestation of the divine feminine. If we did that, we wouldn’t be in the mess that we are today with how we’ve been treating the planet.

WOODS: Oh, absolutely. Penny, let me finish up with one more question. What excites you daily?

SLINGER: Right now, I’m doing my archives. And my process of archiving, it’s kind of overwhelming and big, but at the same time, it’s such an incredible mega-collage of my whole life and art. Everything that’s part of my life is part of my expression as an artist. so to now be able to take all these parts, scan all these photos, digitize all these videos, collating and collecting all these parts of myself, it’s a fantastic experience. And I would recommend it to anyone. This is my legacy and this is my blueprint, and if I make it accessible, this will be an amazing resource for other artists to help them on their path.