OPENING

Artist Nikita Gale Is Watching You From the Nosebleeds

At the opening of the NOSEBLEED exhibition at Petzel Gallery last Thursday, viewers had their gaze fixed not to the walls but to the floor, which was blanketed with a sprawling panoramic image of the view from the so-called “worst seat in the house.” Navigating photographs and 3D-rendered models of large-scale venues strewn across the ground, dozens of gallery-goers busily shuttered their cameras to snap selfies in a wall-length mirror mounted at an angle designed to refract the spectacle of performance back onto the audience. Drawing from the structural and atmospheric elements of Beyoncé’s Renaissance and Taylor Swift’s Eras tours, Nikita Gale, the LA-based artist behind the installation, provoked a heightened sense of visibility and play, challenging our positionality as onlookers: “It’s thinking about the nosebleed as not just as position and a space, but a theoretical, philosophical position,” Gale explained on site. As the clock struck eight and the energy devolved into ambient, white noise, we snuck away with the artist to talk about the history of protest music, Toni Morrison, and the sandworm from Dune.

———

LILY KWAK: How are you feeling about your show?

NIKITA GALE: I’m feeling really good about it, relieved. The install was really smooth, super easy. It’s interesting having a show so soon after the Whitney Biennial opening. But it felt really nice because it feels like those two works are very different. I feel like I have these two modes of making: one’s very discrete, standalone objects, and then the other is this sprawling installation with lots of little moving parts.

KWAK: It’s funny to see wealthy gallery-goers in Chelsea navigate nosebleed seats.

GALE: Right. [Laughs]

KWAK: But it seemed everyone was walking in and immediately the first thing they were doing was taking a picture of themselves in the mirror. Were you expecting that kind of response?

GALE: I mean, I think there’s something inherently provocative about mirrors, and there’s also something about just the structure of lots of modern arenas and stadiums. They’re essentially mirror images, these perfectly symmetrical spaces. So if you’re sitting on one end, you’re essentially seeing sort of a reflection of the side that you’re on. But yeah, it is thinking about the nosebleed as not just a position and a space, but a theoretical, philosophical position.

KWAK: Everyone was walking through the installation and apologizing to each other, trying to…

GALE: Right, like, “Excuse me. Excuse me.”

KWAK: Yeah, you’re crawling into spaces…

GALE: Crawling over people. Yeah, that’s definitely a part of the work. Because another thing I was thinking about with the show is that position your body takes on when you’re in a nosebleed seat. You’re essentially looking down at whatever the action is or whatever the subject is. So the gallery really causes you to replicate that position. You’re looking down at everything. But then you have this angle-reflective mirror that turns the floor into a kind of wall, but it also doubles the distance of what you’re seeing. So things feel further away, even though you might be right next to them physically.

KWAK: Right. I wonder, was there like, an eerie white noise before everyone started drifting in?

GALE: Yes. So the installation lights and mechanical equipment often have these ambient noise levels that are typically hard to perceive unless everything around is silent. So usually with lighting, there’s a lot of loud noise, or there’s speaker arrays that are projecting hundreds of thousands of watts of sound energy so you don’t hear that stuff. But in this space, because there’s no other sound element, the sound of the lights is really highlighted. So if you’re in there by yourself, there’s just white noise.

KWAK: I’m really interested in how you work with sound. I don’t know if you’ve been reading in the news about a Columbia professor, John McWhorter, who went ahead and wrote this whole piece in The New York Times about how he’s trying to lead a class, and he’s throwing a fit that he can’t play John Cage’s 4’33. He’s like, “I can’t hear the birds and people idly chatting because it’s being consumed by the sound of student protests.”

GALE: Yeah, it’s funny that he referenced that piece specifically because that work is about the very thing that he’s complaining about, which is that the work changes in its context and it’s not about hearing just the ambient sound. It’s about hearing whatever’s around the space. It becomes a part of the work.

KWAK: Exactly. Cage was interested in offering an opportunity for people to be in intense presence with each other, and he wanted the audience and their interaction to be part of the work’s soundscape, which is also what your installation amplifies.

GALE: Yeah. I don’t consider myself a sound artist, but I do consider myself someone who is interested in the context of sound and the context of performance and the things that might be happening around whatever the sound object is.

KWAK: I was conscious of people navigating the floor with me and felt like we were sharing a similar experience. But also like, “What are you thinking? What are you feeling?”

GALE: That’s one of the things about installation work too, is that it can operate on so many different levels that there could be, for every person in that room, another version of the work. And I think about this with performance as well. For every person in the room, there’s essentially a new work that’s being produced.

KWAK: I was also looking into more of your past works as well, and, this is a very loose quote, but you said something about how, when we speak about sound, we’re also speaking about touch. That reminded me of how, on campus when there’s counter protesters coming in, the pro-Palestine protesters are very careful not to be receptive to their aggression and violence. Instead, they’ve been using songs, lines with biblical references, to forge a sense of community amongst themselves, but also to generate a protective shield outwards.

GALE: Yeah, I think there’s also a very long history of the use of sounds, and particularly music and song as a tool of protection, but also it’s the way that history is often shared. There’s a… god, it reminds me of this Tony Morrison novel, Song of Solomon. There’s this moment in the novel where the main character, Milkman, encounters this song and then he realizes that at some point, one of the names had been changed, but it was actually the story of this real event that happened. And it becomes key to unlocking this mystery. Also, the history of protest songs, the way that music is often one of the last safe spaces for political expression. I feel like that’s a conversation that’s been going on for centuries. And for many cultures, some of the earliest documentation of certain art forms is only because someone who had more resources or power thought there was something valuable about it or something that could be commodified or exploitive. There’s a lot to think about with this idea of sound as protection, protest as protection.

KWAK: With your Biennial installation, you were looking at the political function of noise and silence by homing into often invisible, affective labor. Here, with Nosebleed, I was thinking about the silence when I first walked in and then felt like I was expecting or anticipating something. Maybe that’s the beginnings of creating a spectacle of the performer.

GALE: I’m glad you brought that up. The large image on the floor is a really loud image. The energy of it is very loud. There is something that feels jarring in terms of the expectation versus what you’re actually experiencing.

KWAK: Nosebleed I looked like the sandworm in Dune.

GALE: That is so funny because some of my friends were showing me a picture of the sandworm from Dune yesterday when they came to the preview. And I was like…

KWAK: The sandworm is supposed to be an agent of God or a form of divine intervention.

GALE: Yeah. That’s interesting.

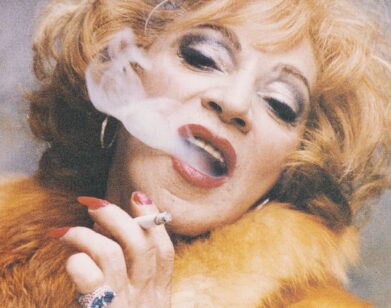

KWAK: I know you’re very influenced by Tina Turner and reference her a lot. You talk about how desire is data for you, so you really like to dig into things that call your name. How do you understand cultural icons like Tina?

GALE: Yeah, I mean, whenever I encounter something that I sort of have, it’s not necessarily an obsession, but something that draws me to the image or the sound or the space, I know this isn’t some neutral experience. It’s informed by all of my experiences and my particular subject position as a consumer of culture, as a producer of culture. There’s a lot to be unpacked.

KWAK: Yeah, I operate the same way.

GALE: It’s just like, well, there’s something that’s informing that. I want to understand what the structure is and pick it apart. One of the things that comes up in the show a lot is just stadium structures. The experience of moving through the stadium, experience of going to a show from the very beginning of just going through the seating chart and deciding what seats I’m going to get, which is part of the…

KWAK: Were those the groups of shards littered on the ground?

GALE: Yeah, the little aluminum shapes, each of those is the shape of a section taken from a concert seating chart for either the Beyoncé Renaissance tour or Taylor Swift’s Eras tour. That’s the beginning of the spectacle before you get there, deciding where to sit.

KWAK: Nosebleed III made me think of a reverse panopticon. It’s like, yes, we’re being surveilled by people, but we’re also very complicit in it.

GALE: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think that is a really foundational structure to think about this kind of relationship to surveillance. Also, the aerial shot, the viewpoints of many of those images are looking down from above. And so the nosebleed position has a really… It’s not quite the surveillance position, but it’s closer to it than any other position in the stadium, just because of the height.

KWAK: Right, right, right. And especially with your obsessions with Tina Turner or Beyoncé, I find a lot of connection with Warhol. They probably both knew a thing or two about creating the self, myth-making. I saw that post on your Instagram with Warhol and Tina Turner biting into a watermelon together coming out of a nightclub in Atlanta.

GALE: Yeah. A lot gets projected into those images, too. It’s one of the things about constructing a public image or having this public persona, spectators project a lot onto them, which simultaneously makes them very successful. But there’s also a certain kind of vulnerability to that.

KWAK: Okay, closing question.

GALE: Yes, let’s do it.

KWAK: What’s your favorite live Tina Turner performance?

GALE: I really love the scene from Scorsese [that uses] “Gimmie Shelter,” the Rolling Stones. It’s this two-and-a-half minute scene of Tina, and I think that’s my favorite footage.