IN STUDIO

Artist Lynn Hershman Leeson on Cyborgs, Filler, and Film-Snobs

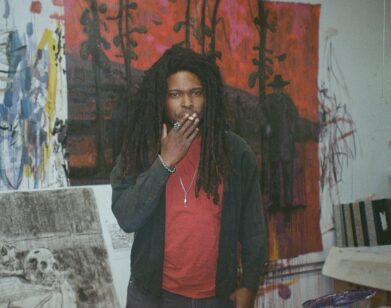

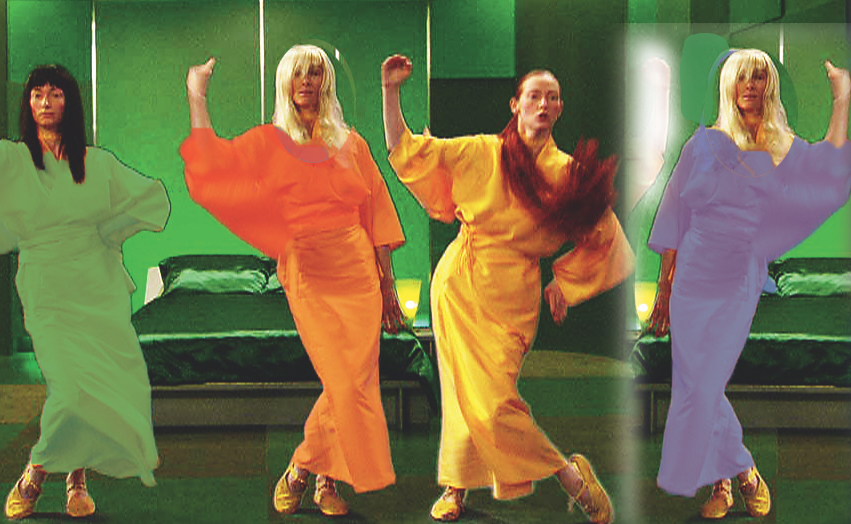

Still from Cyborgian Rhapsody (2023).

The artist Lynn Hershman Leeson has long been overlooked and ahead of her time, exhibiting her art for the first time at the age of 73. Her work explores the intersection of humans and technology, the confluence of which she has long pioneered with her use of artificial intelligence and custom software. Anti-Aging, currently on view at Bridget Donahue on the Lower East Side, features drawings, installations and videos spanning seven decades. Included therein is Cyborgian Rhapsody, a short video featuring a cyborg named Sarah who sports a purple halter-neck dress and aviators. Miraculously, the character is self-styled, reciting a script of their own making. “I could have done it better, but the premise was that I had to do what Sarah said,” the 83-year-old artist told me last week. This coming June, more of Leeson’s films will be spotlighted in a series at MoMA, including the many works made in collaboration with the actor Tilda Swinton. Just after the opening of Anti-Aging, Leeson joined me on a call from San Francisco to discuss “Instagram Face,” Yohji Yamamoto, the contemporary art world, and why on earth she has five iPhones.

———

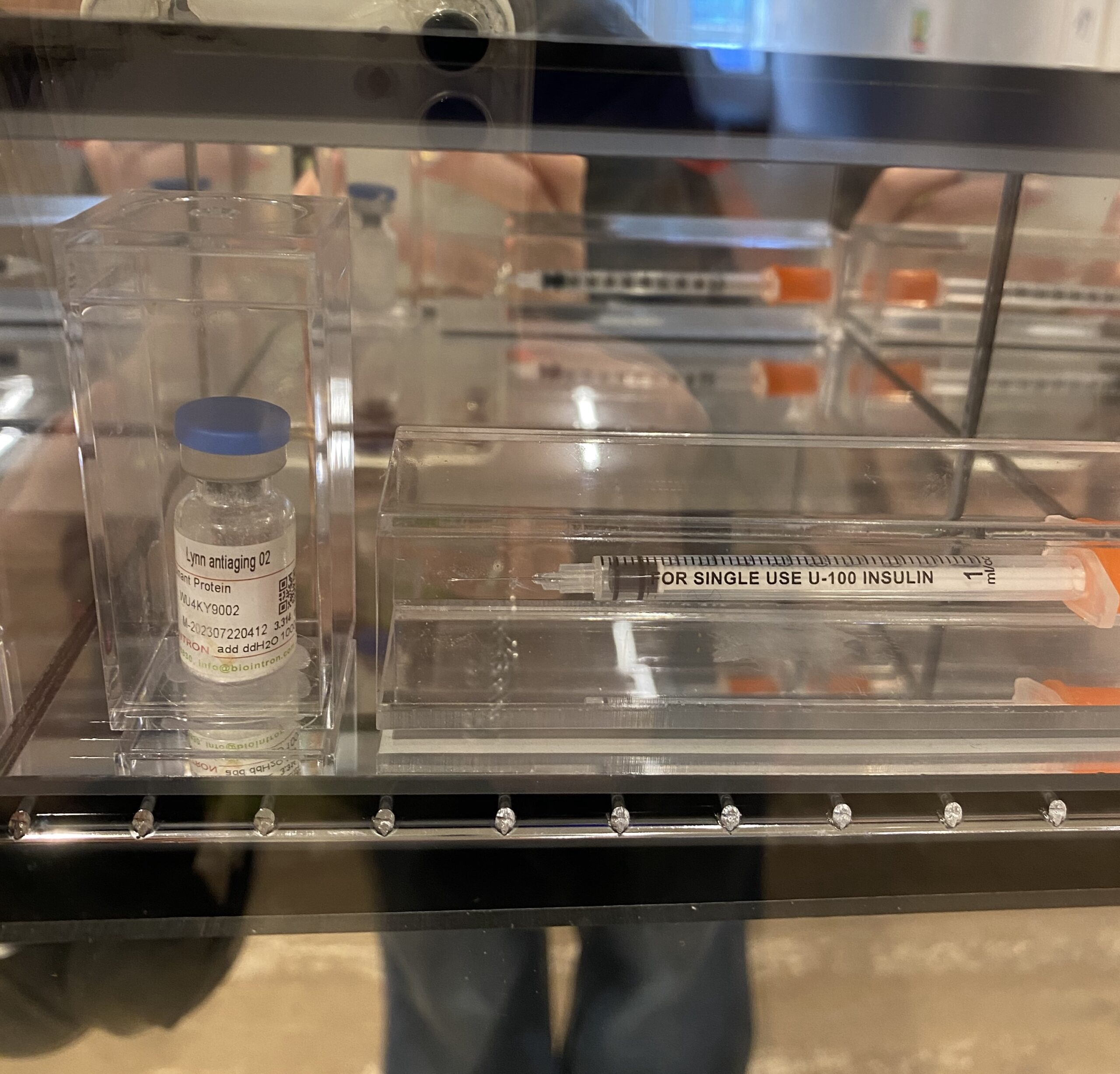

EMILY SANDSTROM: The show up right now is called Anti-Aging. I want to talk about the vaccine that’s in there. I read that you ordered it from a lab in China and that you were fascinated with newer ideas that view mortality as something that can be cured. Is that the type of vaccine that’s meant to freeze cells or regenerate them?

LYNN HERSHMAN LEESON: Yeah. In the back of that piece it says what’s inside of it. It’s got amino acids and proteins and peptides, but it’s meant for cell regeneration. It’s illegal to do it in the United States. It’s illegal to do it in Europe, so I had to go to China in order to get it from a lab. They can do it here, but they have permission for rats, not for humans.

SANDSTROM: Did they ship it to you, or did you go there to get it?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Oh, no. They shipped it to me.

SANDSTROM: Oh, cool.

Eternally yours, 2023. Unique anti-aging powder, syringes, specially designed refrigerator, mirror plexiglass, framed order form.

HERSHMAN LEESON: I worked with the same scientists that I worked with to put my work into DNA a couple of years ago, because DNA has a memory of 500 years instead of 50. He was the one that found the place.

SANDSTROM: So, your DNA went… Wait, where did the DNA go?

HERSHMAN LEESON: It’s synthetic DNA. I took all the research I had been doing and my diaries and put them into DNA on a molecular level. So, I have this thing that’s this big and it’s invisible, and it’s my whole history.

SANDSTROM: Oh. Does that mean we could clone you at some point?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yeah. You’re able to project what’s inside of it. It takes a while, but you could do it. And it’s only going to get better and easier and faster.

SANDSTROM: The vaccine that’s in the show, would you take it? Is mortality a good thing?

HERSHMAN LEESON: I mean, it’s what we’ve always been doing. We always live with the assumption when we’re young that we’re not going to live forever. Although, my mother told me that I would because I used to freak out about dying. That element where everything is transient and temporary may make one more aware of what they do in their life. If you thought you were going to live forever, you would never clean your clock. You’d procrastinate anything that was difficult to pursue. It gives us that timeframe of possibility to work towards having memories or something to leave for the next generation.

SANDSTROM: You were struggling with medical issues from a very young age, right?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yeah. I lived my life in reverse because I was sick all the time when I was young and when I was pregnant. I spent months in hospitals, and as I got older I got better, so knock on wood, I’ve been fairly healthy now.

SANDSTROM: That’s amazing.

HERSHMAN LEESON: When you don’t know if you’re going to be able to live the next few months, that makes you value what you do with your time.

SANDSTROM: Would you ever take the vaccine that’s in the show?

HERSHMAN LEESON: I wouldn’t do it right now.

SANDSTROM: But maybe in the future?

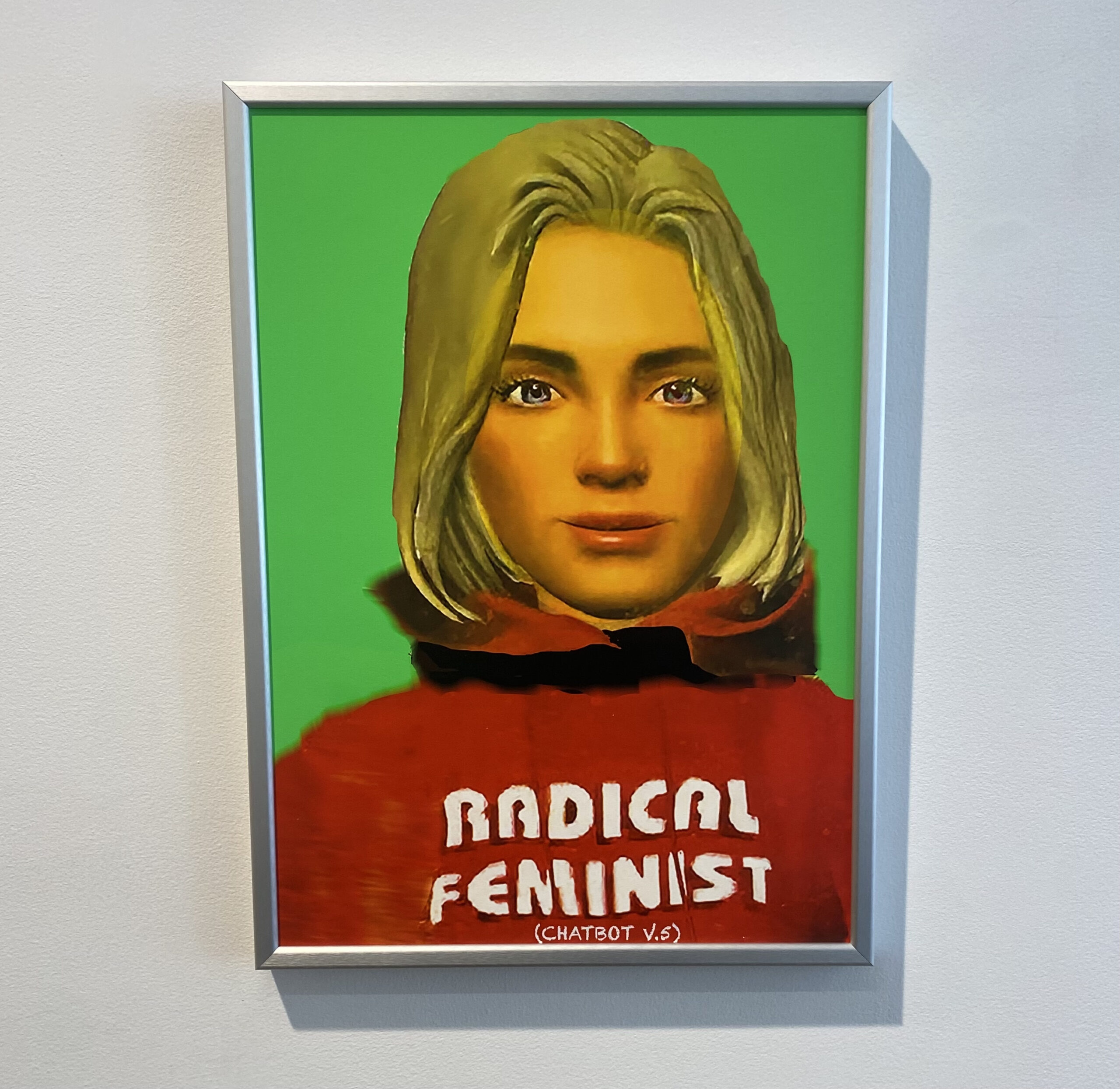

Radical Feminist Chatbot, 2024. Archival pigment print.

HERSHMAN LEESON: Maybe when they’ve tested it on someone else. I don’t know if I’d want it because not many people my age would take it or wouldn’t even know about it. I’d have to really think about that. The fragility of life and the fact that it’s temporary is something that’s too ingrained in me. Then also if I took it, what about all the people like my daughter or my husband, all the people in my life that didn’t take it? It would be very lonely.

SANDSTROM: Totally. Your work addresses humans intersecting with technology, and I was thinking about how younger generations are now obsessed with skincare and fillers and Botox, and how easy it is to augment the human form now. I’m wondering, do you know what “Instagram Face” is?

HERSHMAN LEESON: No. What is it?

SANDSTROM: It’s like, when people online all look the same because they get similar surgeries that change their features. Like getting your eyes lifted or lips filled. So, in the spirit of anti-aging, what do you think about people embracing those things? How does that make you feel, just on a visceral level?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, I really value uniqueness. I can see that there are certain programs that aren’t really flexible, so they make everyone look the same. I wouldn’t want to do that. I’d rather look older or not look like everybody else and keep the special elements that maybe aren’t so compelling, but are authentic.

SANDSTROM: Is there something that creeps you out about it?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, one is that people want to do it. Two, that they’re becoming clones of each other, so you have a population of replicants.

SANDSTROM: Right. And this really is the primary way that people are now physically intersecting with technology. This is the most prolific way.

HERSHMAN LEESON: And superficial way.

SANDSTROM: Yeah, things are getting weird out there. I wanted to talk about how your work has always been ahead of its time. Many of the things you were interested in came to you long before they ever formed the zeitgeist. Now there’s a whole generation of kids that are completely fascinated by you and your work and your ideas. Is that frustrating?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, I always felt that I had to wait for two generations down to be born, because when I started doing all of this work it was rejected and not paid attention to. I was 73 before it was first shown. A lot of the work was 54 years old, and nobody had seen anything. On that level, it was frustrating, but it’s great that the people now growing up happen to have this inherent understanding of the world the way it should be rather than the way it was in the past.

SANDSTROM: Yes. When was the first time you started thinking about technology intersecting with creativity?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, when you live in the Bay Area, you think in terms of possibilities of software. If it doesn’t exist, you could find a way to do it. That in itself will create something that hasn’t been seen because it’s a new way of looking at the world. So, I credit living in the Bay Area to the understanding of technology and how it’s connected us in a different way.

Still from Cyborgian Rhapsody (2023).

SANDSTROM: Yeah. I watched this video where you said, “If I had moved to New York and tried to make art there, I wouldn’t have done the things that I’ve done.” What type of work would you have made if you were here? Would it have been more commercially oriented? And what does the commercial art world evoke in you?

HERSHMAN LEESON: I don’t know, because I never fit into the commercial art world. I almost never sold my work except to a couple of random weird people, but if I’d moved to New York, I would’ve tried to be part of that system, which I never would’ve been accepted into anyway. It was only by finding my own path using something that nobody else was doing that eventually I was able to have more resonance in the art scene.

SANDSTROM: Is there anyone making art now that fascinates you?

HERSHMAN LEESON: The only people I find doing interesting work are scientists, not in the art world. I haven’t found many things in the art world that are interesting because they’re all so imitative, and nobody will show breakthrough work, or work that isn’t going to sell.

SANDSTROM: Do you still feel like an outsider?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Less so now because I’m having more shows. I’m accepting more that I’m becoming part of that history.

SANDSTROM: My next question was about Cyborgian Rhapsody, the video that’s playing right now at Bridget Donahue. I laughed when she said she feels discriminated against because everyone has come to fear misinformation. That was all written by a chat bot, right? Did you give it specific inputs?

HERSHMAN LEESON: No. Sarah wrote it, and I would’ve done it differently because Sarah didn’t have a sense of humor. She didn’t know metaphors. She didn’t know layering.

SANDSTROM: Sarah is the name of the character?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yes. She named herself after Sarah Connor, but it doesn’t have a gender because it says gender gets in the way. I would’ve written it differently. I could have done it better, but the premise was that I had to do what Sarah said.

SANDSTROM: I was very taken by their halter neck purple dress and their glasses. Did they style themselves?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yes.

SANDSTROM: Did you like what they came up with?

HERSHMAN LEESON: It didn’t matter. I just did it as a point of interest that you could have an AI that represents itself, names itself, and tells its own story. Its sense of narrative was more like an Instagram scroll than any other format.

SANDSTROM: When you say Instagram scroll, does that speak to some vagueness or absence of character?

HERSHMAN LEESON: It’s more that there’s no metaphor.

SANDSTROM: Right. Another question regarding styling is about Teknolust, which I watched many years ago. Could you tell me the origins of your long collaboration with Tilda Swinton? Also, how Yohji Yamamoto ended up coming in as the costume designer, which is so cool.

Stills from Teknolust (2002). Courtesy of the artist.

HERSHMAN LEESON: When I did it, I was really lucky because I got German television. I taught myself how to do video, and I sent them into some competitions and it won. Then, German Television commissioned this. It was one of the first projects that actually had a budget. I sat next to Tilda Swinton at the Berlin Film Festival, that’s how I met her. It was accidental and we just started talking. Conceiving Ada, we had to shoot in a week because I had such a small budget. And I asked Yohji Yamamoto because I liked his clothing, and he said yes. I find that most times you just have to ask people and they’ll do it.

Stills from Conceiving Ada (1997). Courtesy of the artist.

SANDSTROM: So it was a German Television network–

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yeah, ZDF. Unlike America, they support artists, so they commission artists. They give you a certain budget. You could do what you want, pretty much.

SANDSTROM: Awesome. I read that the movie got booed at Sundance?

HERSHMAN LEESON: All my movies. Every movie I ever made got booed at Sundance.

SANDSTROM: Were you there?

HERSHMAN LEESON: In Toronto and Berlin. Less in Berlin than other places, but they all got booed. They never got picked up. They never got distributed, and pretty much caused me to nearly go bankrupt, which is why I can’t make one now. I feel at my age, I can’t recover from bankruptcy, so I’m very cautious about doing it again.

SANDSTROM: Yeah. Well, film snobs and cinephiles, they’re some of the scariest people out there. But MoMA is doing a film series of your work this summer, right?

HERSHMAN LEESON: They’re going to do my films. June 7th it opens.

SANDSTROM: I have an image of Phone Sleeper in front of me, the mannequin who’s got all the phones. Why do they have so many devices?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Because I do.

SANDSTROM: How many phones do you have?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Maybe five.

SANDSTROM: Really? Why?

HERSHMAN LEESON: In case I lose them. Or I upgrade them, and then don’t send them back for refunds.

SANDSTROM: I see. I read this scene as how my generation lives, accidentally falling asleep next to your laptop or phone or speaker. Is it meant to reflect that?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Yeah. It’s a portrait of that generation.

Phone Sleeper, 2023. Twin size bed, mannequin, bed sheets, 7 cell phones, 1 ipod touch. Courtesy of the artist.

SANDSTROM: Okay. Home Front – Cycles of Contention is one that I have here also. I watched the video where you can hear them arguing. How did you land on a domestic dispute for this installation?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, if I’m to tell the truth about it, the two actors were my students. I had a basic script set up, and they started fighting.

SANDSTROM: Oh, really?

HERSHMAN LEESON: It wasn’t in the script.

SANDSTROM: Then you did love it?

HERSHMAN LEESON: I liked it.

SANDSTROM: I never would’ve guessed. It’s so well performed. During that period of time, what about domestic environments interested you?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Well, a lot of my work is about dysfunctional families.

SANDSTROM: So is this work cathartic?

HERSHMAN LEESON: No. It’s just a way of looking at life.

Home Front – Cycles of Contention, 1993-2011. Dollhouse, dual-channel video, paint, custom electronics. Courtesy of the artist.

SANDSTROM: That’s great. Well, is there anything else you want to talk about otherwise?

HERSHMAN LEESON: No.

SANDSTROM: Are you watching any good TV or listening to any good music?

HERSHMAN LEESON: No.

SANDSTROM: Okay, great. Wait, can I take a selfie of us on my phone?

HERSHMAN LEESON: Okay.

SANDSTROM: Thank you!