gallery walkthrough

The Artist David Chatt Embraces The Seductive Power of Tiny Beads

Photo courtesy of the artist.

For much of his life, David Chatt has directed his attention to trash. “I’ve saved every wishbone that’s come across my horizon over the last decade,” says the Iowa-born artist, who spent his upbringing relentlessly preserving and cataloguing everyday detritus (like soda can tabs and matchbooks) in tall glass jars. While his commitment may seem to border on the obsessive—and he’d likely agree that it does—the 61-year-old sculptor is less captivated by the individual components than by the power and process of their accumulation. “I really do believe that enough of anything is interesting,” he says via Zoom from his bead-strewn Seattle studio, “I’m always looking for new ways to immortalize the things that people cast aside.”

Chatt, who defines himself primarily as a sculptor, has distinguished himself by sewing elaborate still lifes—a man confronting his sagging reflection in the mirror, an elaborately laid out breakfast, a cluttered bedside table—entirely from minuscule glass seed beads. His pieces are held by the Smithsonian Museum of Art, New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, and the Boston Museum of Fine Art, allowing him to bridge the imagined divide between the realms of craft and art, “craft just means an object has a use, and that’s a line that I like to blur,” he says. The still lifes, which can take years to finish (a single toy soldier alone requires a day), reveal a degree of patience that is staggering in today’s world— the rumpled cartilage of the inner ear, the marbling on a strip of bacon, the wrinkled fabric of a shirt take shape through the meticulous stitching-together of beads with just the slightest variation in hue.

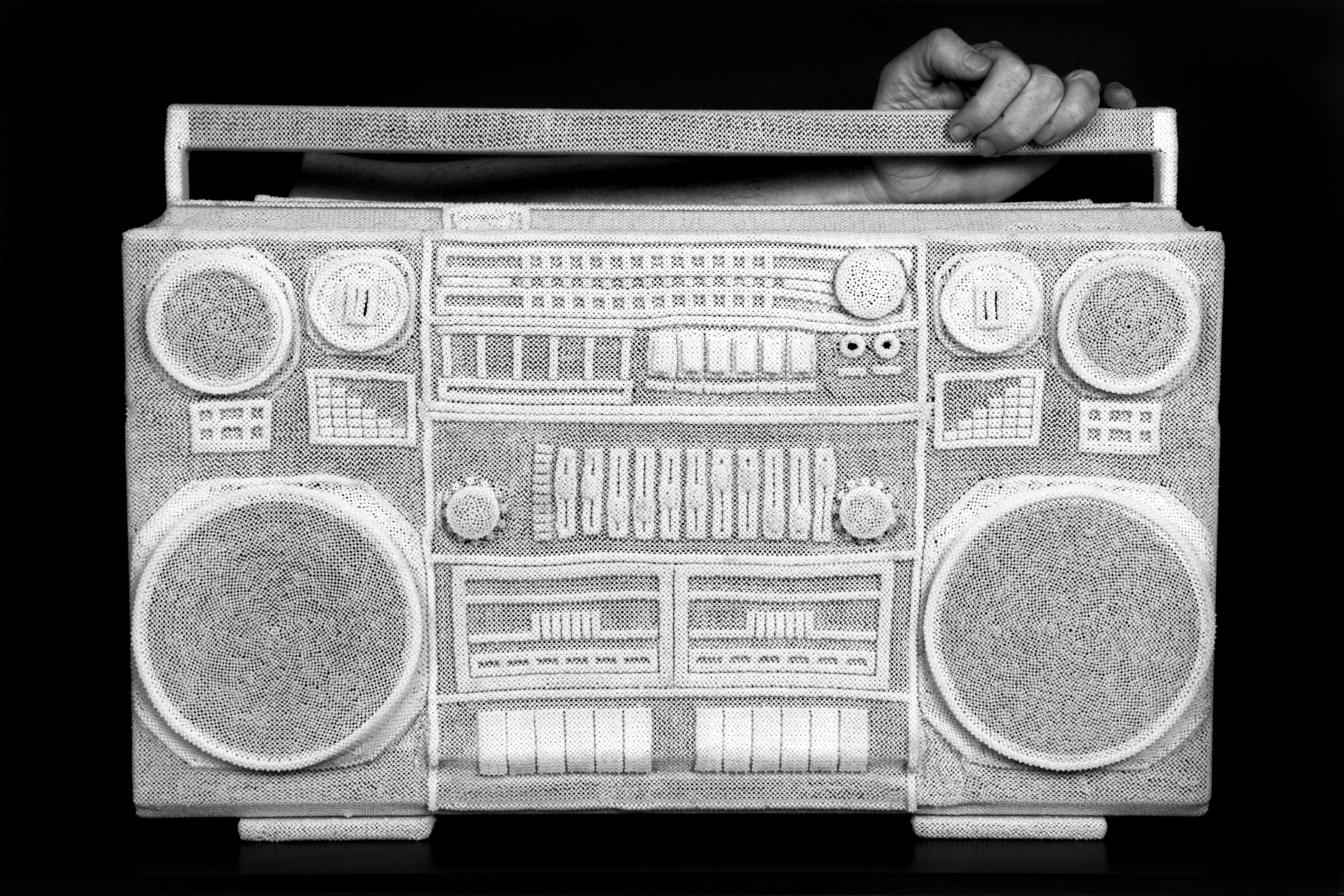

In recent years, Chatt’s focus has shifted slightly: he went from constructing beaded objects from scratch covering things in a close-fitting and eerily undetectable beaded skin. This month, fruits of Chatt’s latest labors are on display at the Sienna Patti Gallery in Lenox, Massachusetts. The pieces, for the most part absent of color, are in many ways commemorative—a boombox memorializes Chatt’s experience during the AIDs crisis, a culinary scene honors his late mother—lending them a ghostly weight. To celebrate the show’s opening, the artist took a moment to discuss the dying art of patience and, yes, “the seductive power of beads.”

———

“Toy Soldiers.”

“There’s a lot of irony in my life and work. I’m a guy who’s six-foot-five and sews tiny beads together, and I grew up in the age of automation and mass production. It’s completely impractical. But it’s interesting, in such a fast culture, to make work that cannot be hurried, in which the process is evident.The larger pieces take months of continuous work, so I always have something in my hands. I’m sewing while I’m talking to you. If I concentrate, I can make one of these in a day. But it’s a long day. I started the toy soldiers because I’m always on the lookout for an iconic image sticks in people’s minds. It’s harder than you’d think to find something that still resonates with people when its covered in a layer of beads. This just worked—it still looked very much like that iconic little soldier that all little boys played with, but they’re abstracted enough that you don’t immediately know what they are. Most people don’t think twice about the fact that every little boy had those plastic soldiers. I don’t remember anybody giving them to me, I don’t ever remember wanting them, I just remember having them. At the same time, we all just sort of understand that it’s predominantly men who create violence in our society. You don’t see a whole lot of mass shootings by women.”

———

“1982.”

“A big difference between this body of work and my earlier projects is the absence of color. These pieces are less about the seductive qualities of glass beads—color and movement. When you take some of that away, it becomes about the meditative process of making something. This one took me a year or so to finish. It’s about the negative space where the boombox once was more than it is about the boombox itself. While I made it, I kept thinking, ‘Oh, I should listen to some of the music that I listened to when I was lugging a boombox around.’ That brought back all these memories of living through the AIDS crisis as a gay man, and gave me a sort of post-traumatic stress, I think. A lot of that music is tinged with melancholy for me, so this really became about the silent boombox. I think that’s a pretty interesting metaphor for time, and for all the voices that were silenced. It has this sort of ghostly quality now, right? I also love that it’s beautiful.”

———

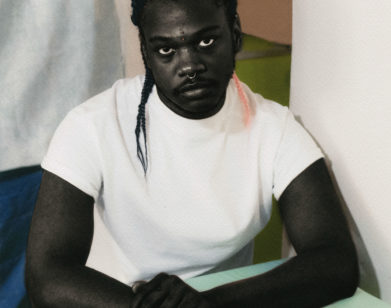

“If She Knew You Were Coming.”

“I think that the line between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ is certainly a lot blurrier than it used to be. Usually, if something has a use, it’s considered craft. I think of myself as a sculptor, but I don’t really care what people call my work, it comes from the same place that art comes from. I take a lot of pride in the fact that I’m really good at what I do, and that’s the craft part of it. This one’s about my mother. It’s a combination of things that meant something to her. My mom used her kitchen like a studio, like I use my studio. She was also a professional nurse, and she taught nursing in college, but something that I hope comes through is a recognition of the tedium of raising children. Think about all of those beads strung together, all of the lunches she made, and the tubs of laundry she did. She was tireless, and there were six of us. Every object on the table is covered in beadwork, with the exception of the dishcloth, which I made from scratch. It took me a full year to make that collection.

———

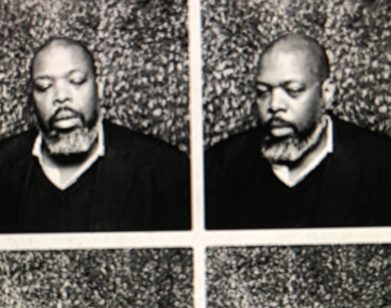

“Love, Dad.”

“My dad was a letter writer. For a long time, he would send me a letter or two a week, even though I only lived 90 minutes away. He didn’t like to talk—he kept a lot to himself. They were usually nothing letters, just some advice or some updates on what he and my mom had gotten up to that day. Eventually I began saving them, and by the time he passed away, I had a crate full of them. At that point, the collection became complete, in this way, and it was just a whole box of sad. I couldn’t bear to read them, and I didn’t know what to do with them. I wanted to find a way to contain them that allowed them to be seen but not read. A few snippets are visible here and there—’I went to Goodwill today,’ or ‘I saw a friend’— but for the most part they’re kept pretty private. There’s a key to the lock in the drawer. It seemed like a perfect way to sum up who my father was.”