RETROSPECTIVE

Artist Christine Sun Kim Doesn’t Want to Be Your Inspiration Pornstar

The title of Christine Sun Kim’s lecture, “Deaf Death,” which I saw recently at The Whitney Museum, is sort of a joke. When you type “deaf” in iMessages, the iPhone auto-corrects it to “dead.” Yet Deaf culture, rooted in sign languages like ASL (American Sign Language), might actually be dying. One of the lecture’s slides displays a New York Times article titled, “Gene Therapy Allows an 11-Year-Old Boy to Hear for the First Time,” detailing a 2024 clinical trial that allowed a boy born Deaf to hear for the first time. It’s possible that this new gene therapy may one day make ASL, Kim’s native language, a dead language, much like Latin.

I’ll just say it: American Sign Language (ASL) is vastly superior to English. Written ASL employs more modes of signification than English, including the index, the pictograph, or the use of line to represent time. Manual ASL employs facial expressions to convey emotions, but also syntax. I don’t believe what they say about how one’s command of language directly correlates with one’s complexity of mind. But if this were true, Deaf folks would be the most complex people alive.

While a lot of art by disabled artists is often simplistically classified as “what it’s like to be me” empathy art, Kim’s is on a whole different level. She resituates post structuralist paradigms by combining various modes of communicating in a notation entirely of her invention. Her mid-career retrospective at The Whitney Museum in New York, on view through July 6, rewards viewers who take the time to learn how to read her writing, but it’s also immediately accessible with English subtitles, cracking jokes about Asian Flush and loving McDonalds. We got together recently at The Whitney and chatted about her latest work, and how I also love McDonalds.

———

GEOFFREY MAK: I was really inspired by your lecture last night. You were talking about how you wanted to avoid becoming “inspiration porn.” Tell me about how you navigate that.

CHRISTINE SUN KIM: In the beginning of my career, I did allow that to happen a little too much. Starting out as an artist, I couldn’t really be choosy. It’s like, “Fine, I’ll play that card. I’ll play this game as long as I get my foot in the door while doing so.” I figured once I got my foot in the door, I could then better control my path and narrative. But starting out, it was so hard to do that. Especially when I was oftentimes the first deaf person anyone I encountered had met. And I get it, but I don’t love it. I found that I was thinking like them when I met them. But I don’t want that language in my head. Now I have an access rider, and it reduces these reactions. My comedian friend Andrew Fisher used the phrase “inspiration porn star” and I thought that was so funny that I wanted to include that in my talk. I’ve noticed that I attract more “inspiration porn” reactions from those who are not artists, who maybe are looking superficially at my art and then find out that I’m a deaf artist. It’s a lot for them to take. Those who are not artists really love the inspiration porn lens that they’ve put on my work and on me. I feel like people who actually have friends who are disabled won’t say this kind of thing. Do you have any disabled friends?

MAK: I have a few.

KIM: Good.

MAK: When I try to describe ASL, specifically manual ASL, it’s so difficult because it is not like spoken English at all. Part of it is that it’s so much more expressive than English. In your work, humor and nuance come through clearly and immediately. Last night you were talking about how you developed a sense of humor when relating to hearing people. Tell me about that.

KIM: I don’t necessarily think that ASL is any more expressive than English, but I do think that ASL has the ability to perfectly describe an idea and/or a feeling more than English can. English has the ability to explain some specific ideas better than ASL. Sometimes you have a specific idea and you have to figure out if it’s better suited to be expressed in English or in sign language. Sign language, by its modality, ends up being more expressive because it’s seen. It’s not that exciting to watch somebody talk in a spoken language. It’s always going to be more exciting to watch somebody sign. And then humor; for me, it’s a survival skill. When I meet people, whether I have an interpreter with me or not, that social situation will bring forward a reaction from hearing people trying to figure out what to do with themselves. Some people resolve that quite quickly in their reactions, and some don’t. In deaf culture it’s common for us to touch shoulders to get people’s attention, or because I know they’re hearing, I might bring my phone out to text them. I have to initiate a lot. But I find that jokes help hearing people move on from the shock of engaging with a deaf person. “Prolonged Echo,” which is the mural that takes over the third floor, speaks to that experience. Everyone thinks that when they talk to somebody, that person should be able to hear and talk, but not everyone communicates that way. Using humor has been one way to get people unstuck from those moments. Also, I don’t want to have to deal with people’s inability to move on. Humor helps me figure out whether they’re going to be able to move on or not. It also helps me figure out if we’re going to be able to move on in this conversation together or not, or if they’re just going to stay in this shock state. A lot of my work is about my life, and sometimes I’m in denial about it. I am starting to ask myself if I’m in fact moving on. I’ve had the same questions one way or another for the past 13 years, and maybe because of this exhibition, I can move on.

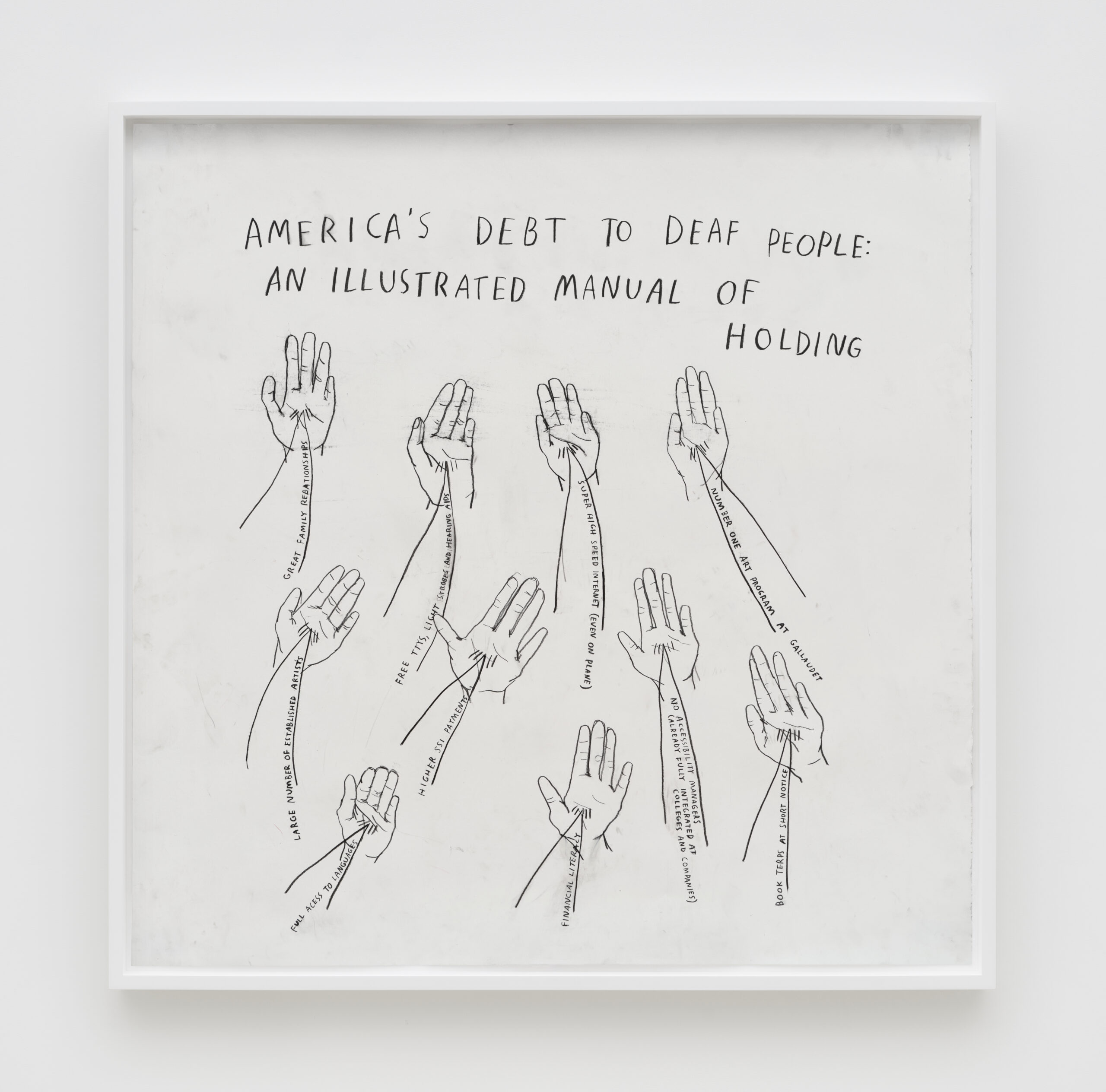

Christine Sun Kim, America’s Debt to Deaf People, 2022. Charcoal on paper, 44 × 44 in. (112 × 112 cm). Collection of Jackson Tang. © Christine Sun Kim. Courtesy François Ghebaly Gallery and WHITE SPACE. Photograph by Stefan Korte.

MAK: I have had this crazy identity crisis lately. My schizophrenic diagnosis actually changed; it turned into PTSD with psychotic features. I hear voices, but why I hear voices has changed. That was a really big shift in my life. Institutions have labels that really affect you and you don’t have control over it. Last night you were talking about this German ID card that said you were 80% disabled, and you don’t even agree with that. What was that like for you?

KIM: I have to consider the fact that I live in Germany and I’m living within those structures. And because of the history of Germany and the sensitivities around that, being labeled 80% disabled felt a bit like recalling Nazi history and the practices they had of measuring personhood and disability. Don’t forget your German history. I had my second daughter through in vitro fertilization. Don’t quote me on this, but some countries will let you pay extra to pick the sex of your baby. I had heard about this from an American friend of mine, and so I asked my German doctor if that was the same here in Germany, and she was flabbergasted that I would ask, because it speaks back to Nazi history and their medical practices. They measured all parts of human bodies and traits. But it was interesting that they would never do that for IVF, and yet disability is measured on a scale. Being disabled in Germany feels different than it does in the US. Putting that aside, I am not disabled first in Germany. I am Asian first in Germany, always. Whereas in the US, in the coastal cities at least, it’s less so about my Asian identity. That’s not what people see first when they encounter me. In Germany, people think I don’t know English.

MAK: Yeah, me too.

KIM: Did you have that experience when you were in Berlin?

MAK: I lived in Berlin for four years, and I knew a lot of Asian-born Asians who knew perfect English with a perfect British accent. It was basically indistinguishable.

KIM: Or an Australian accent. But still, it’s the Queen’s English.

MAK: Yeah, better than mine in some senses. Speaking of Berlin, I was talking to Daniel Chew, our mutual friend who is part of the fashion collective CFGNY.

KIM: I love him.

MAK: He was telling me you love clubbing.

KIM: [Laughs] He would tell you that. Yeah, I love to club. I like how American clubs are so different than they are in Germany. Here, the clubs feel a little bit more about drinking, less so about the music and dancing. It feels more like a meat market where people go to hook up. In Germany, it’s very different. It might help because we’re all on drugs, but you’re very much into your own personal experience of what it feels like to be in your body as you dance. I really enjoy it. Something that I love about the clubs in Berlin is that they’re open on weekend mornings, so then my sleep schedule isn’t all messed up. Look—I’m a mom, I’m an artist, I’ve got a schedule. I can’t really do all-night clubbing the way I used to. But when I do, I love to go on Sunday mornings.

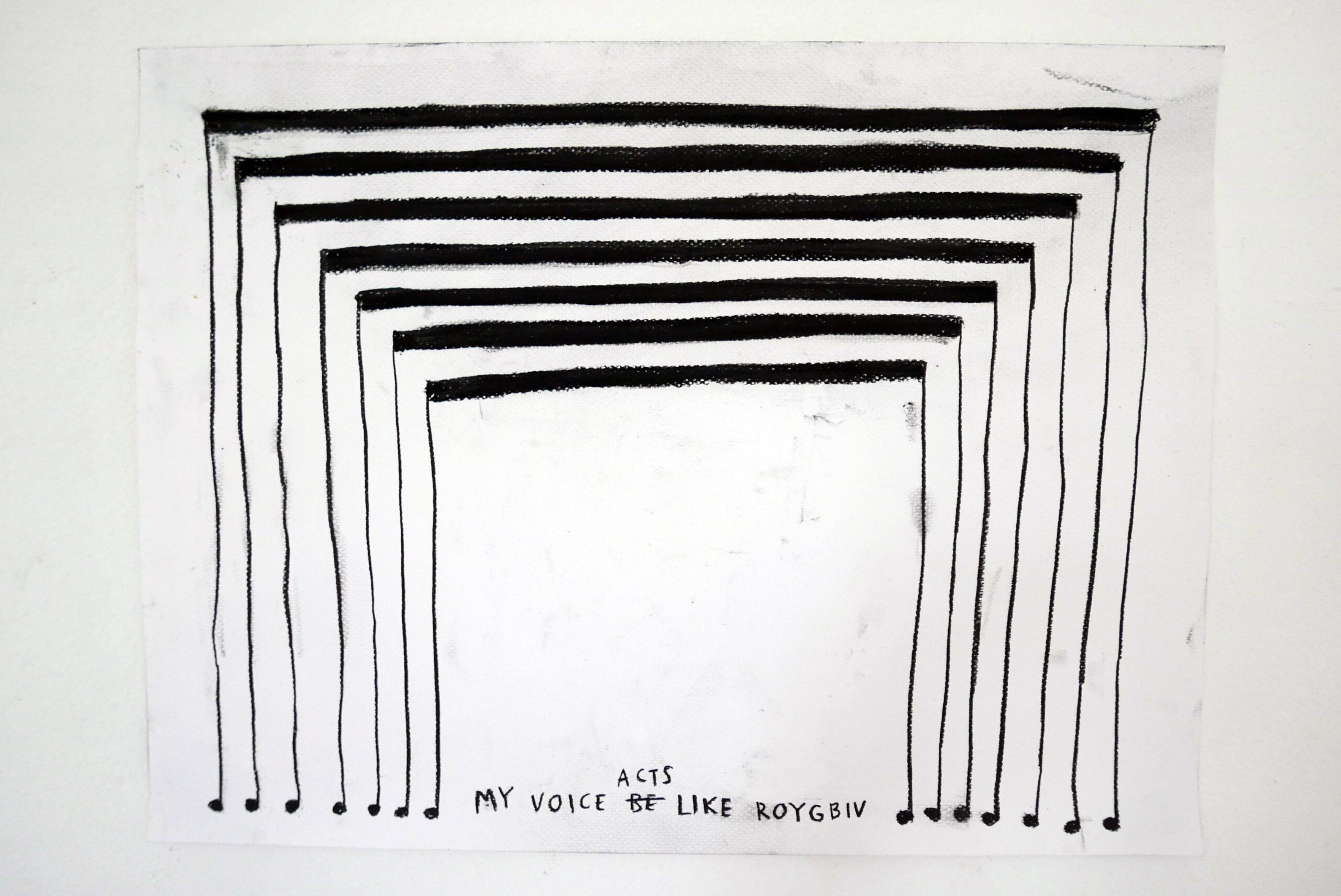

Christine Sun Kim, My Voice Acts Like ROYGBIV, 2015. Charcoal on paper, 11 13/16 x 15 3/4 in. (30 x 40 cm). Deutsche Bank Collection. © Christine Sun Kim. Courtesy François Ghebaly Gallery and WHITE SPACE.

MAK: Something that’s really great about the catalog for the Whitney show is there are all these glamour shots of you in amazing outfits at different events and magazines. You’ve modeled pretty frequently for magazines, and you’re something of a style icon.

KIM: A friend of mine said something similar. She was like, “Oh, Christine, you’re very funny in art, but when it comes to fashion, you’re very serious.”

MAK: That’s funny.

KIM: It could be true. I’ve always wanted to dress like I do now, I just didn’t know how to get there. I want being an artist to be fun, and fashion is fun. It’s short-lived, but I want to live it up as much as I can. I enjoy being able to meet people in fashion. I’m not always the best at branching out of my community into others, but I feel like I’m slowly getting better at that. I work with a stylist now, and I have a few friends who’ve asked to dress me for events. Sinéad Burke, who is the founder of Tilting the Lens, who’s based in Ireland. We became friends on Instagram years ago and recently met in person in New York. She hooked me up to get dressed in Loewe for the opening night.

MAK: That’s beautiful.

KIM: Beautiful dress. It was so nice. They temporarily tailored it to my measurements. The team was just really wonderful. But it was Sinéad who made that connection for me. It makes me feel like I have a different persona when I get dressed. Because, quite frankly, when I’m at home I am dressed in the most boring way. If you were to open up my own personal closet at home, it’s just black or solid colors. I have been wearing the same clothes for five to 10 years. But you see, I put a little effort in today.

MAK: I was struggling to get dressed today. I was like, “I have to look good for Christine.” For the readers, I’m wearing head to toe Raf Simons.

KIM: And you look good.

MAK: Thank you. On top of being a fashion icon, you’re also a mom. You have two daughters. Do they share your sense of humor?

KIM: Our seven-year-old, yes. She’s starting to copy me. When I’m home with her and she gets home from her day, I get upset because she doesn’t tell me how her day went. I start to flip it back on her being like, “Daughter of mine, thank you for asking me about my day. I can’t wait to tell you about it.” Then she’s starting to do the same thing to me. “Well, mother, thank you for asking. I’d love to tell you about my day.” She is full of stories, drawings, and ideas. She’s always criticizing me and saying I need to add color to my work, because it’s boring without color. Actually, you might have seen her work in the catalog. Under the acknowledgement section there are all these colored flowers with their stems and everything, that’s her drawing that I’ve put in the book.

Christine Sun Kim, Long Echo, 2022, Charcoal on paper, 44.5 × 88 in. (113 × 223.5 cm). Collection of Jessica and Marwan Bitar. © Christine Sun Kim. Courtesy François Ghebaly Gallery and WHITE SPACE.

MAK: [In preparing to speak to you], I was thinking about my brother, who is engaged to this Korean man that he met in Korea. They’re not necessarily fluent in the same language. My brother told me that he has to be more earnest in his communication, which has made him a more earnest person. You’re often communicating with hearing people, of course. How is that?

KIM: Is your brother learning Korean?

MAK: He is.

KIM: That’ll help a lot. My husband did not sign when we first met and he’s not one of those fast learners. He is a quick learner for spoken languages and written languages. But because sign language is a different modality, it was not the same for him. He also has bad hand-eye coordination, so we had miscommunications. Sometimes, Tom and I find ourselves looking at each other like, “Wow, we are still together. I can’t believe it. We’re still doing this.” Obviously now it’s fine, but we used to have fights because of miscommunication. But we’re still together and we have two kids.

MAK: That’s fantastic.

KIM: I have a few backgrounds that make me very direct sometimes. Deaf people speak very directly. Koreans speak very directly. Now, I live in Germany and they communicate directly too. Something that I feel like has improved with my relationship with Tom—I used to be like, “I don’t want coffee or tea. You know what? Let’s figure this out together to make a decision.” But Tom doesn’t want to go through that process of deciding. He’s like, “I’m not here for the inner monologue being said out loud in sign language. I’m just here for the final output.” It can be difficult for me at times, but it has helped me decide more quickly and directly. How are you about all of that?

MAK: I’m so bad. I didn’t really learn German. I could speak when I lived in Berlin, but I did feel like I was being more earnest when I talked in German. But I was such a bad expat because I only hung out with Americans, which is kind of why I left.

KIM: I’m not drowning in German friends, to be honest. I think that’s the case for almost everyone in Berlin, unfortunately.

MAK: It’s true. One of my favorite parts of your exhibition is that you outed yourself as a McDonald’s fan. I also love McDonald’s, to the point where I know the different locations and—

KIM: I love McDonald’s. Is it a Korean thing?

MAK: I don’t know, but I know the different locations in the city and the different ways they make their chicken nuggets. I go to the good ones, and they don’t all make it the same.

KIM: Really? I want to know which one is the best.

MAK: The one on the Knickerbocker stop on the J and Z train is really good. The one on the Myrtle-Wyckoff is not so good.