Artist Alex Da Corte looks at the world through the eyes of Eminem circa 2001

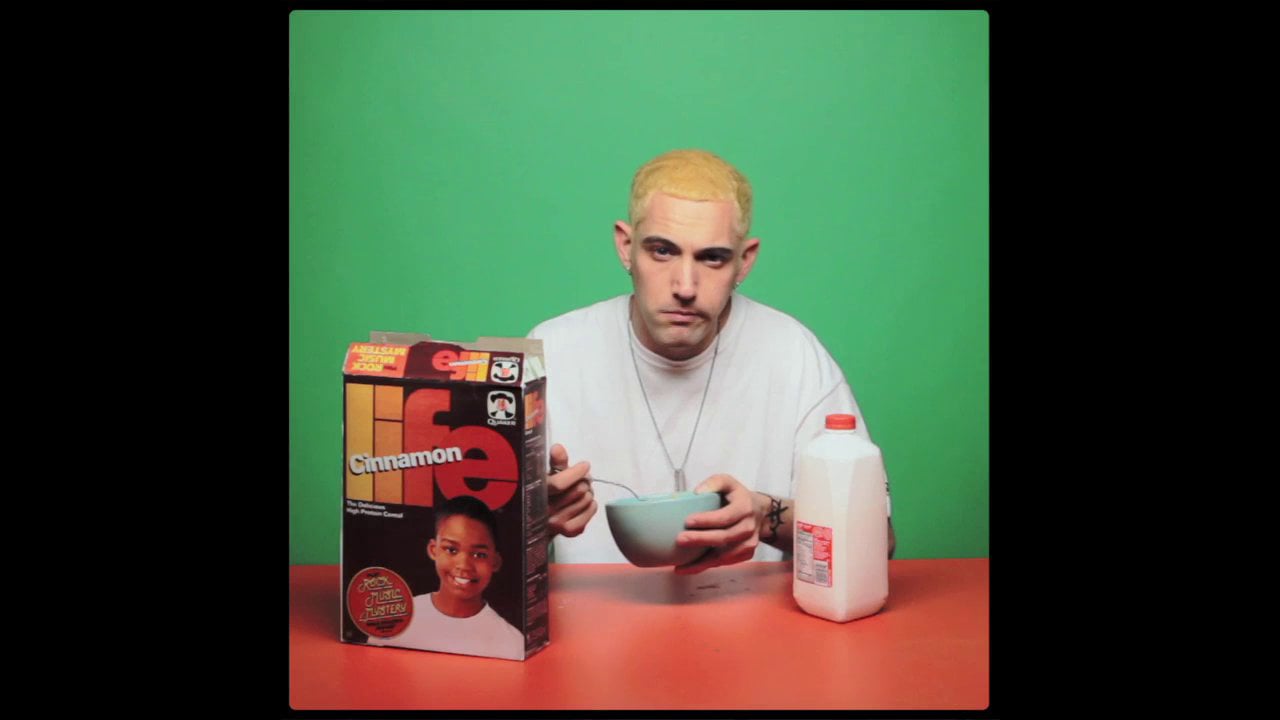

You know an Alex Da Corte piece when you see one. Whether he’s creating massive installations or directing St. Vincent music videos, the New Jersey-born and Philadelphia-based artist has long transfixed us with his striking visual identity. Think primary colors, neon lights, and everyday objects transformed into spiritually charged totems. He exposes spectrums of meaning within basketball shoes and Frankenstein masks, glazed donuts and ketchup bottles. He’s currently six years deep into an examination of Eminem, explaining to me that he “embodies the persona” of the rapper, even dying his hair blonde in order to better “understand the character that he portrayed, the Slim Shady character.”

Fascinated by Da Corte’s sensitivity to the sublime, we asked him to send us a moodboard of images that reflect where he’s at right now. He sent back a sprawling selection of cell phone snaps he’s taken while walking around the Badlands neighborhood where his studio is located in Philadelphia. The images capture an artist with a hungry mind, scouring beneath familiar silhouettes for secret narratives and feelings. Da Corte’s vision is an assault on the idea of mundanity. Think the world is boring? Maybe you just haven’t looked hard enough.

EZRA MARCUS: What can you tell us about these photos?

ALEX DA CORTE: I picked these when I was looking through my pictures. These are all sort of from the last couple weeks. I’ve been preparing for this show that is opening in a couple of weeks in London at Josh Lilley Gallery, called Badland, and this show is loosely based around this project I’ve been doing related to Eminem for the last six years. This show would be the third in a trilogy, so I guess it’ll be the final iteration of this project.

I kind of embody the persona of Eminem and dye my hair blonde and try to understand the character that he portrayed, the Slim Shady character, and try to understand and empathize with who that heteronormative, middle class white male is. So I’ve been doing these shows and as I worked, like many people I gather images. For me, mostly all these images are from the world and I just take photographs with my cell phone. I would say besides one or two images from the group that I sent, everything was taken by me. When I’m thinking about Eminem and these projects, I start to think about what this character wants or what this character would fetishize. I kept coming back to this image of a crown, and I guess there’s a lot of talk about crowns in terms of a kind of success or wealth that’s acquired with a crown, particularly in the field of hip-hop. There’s a lot of speaking about the throne or crown, bowing down even.

MARCUS: There’s a lot of anxiety about who’s on top.

DA CORTE: Yeah being on top and the desire to be on top, coming from the bottom and going to the top. So the motif of the crown is everywhere in culture although we don’t necessarily abide by the same sort of governing that involves actual crowns, like let’s say, London. But there’s this symbol of the crown that still stands for something, like a tattoo of a crown on your leg is a reference to Basquiat or it’s just a reference to power or a reference to royalty; it means something. A lot of the images of these crowns are from places that are uninspired or maybe just kind of prudential. In North Philly, where there isn’t much royalty around, there’s tons of images and branding of crowns.

MARCUS: Maybe this is too literal, but are you imagining that you are Eminem when you’re taking these photos, or is it more abstract than that?

DA CORTE: I think it’s more abstract than that. I don’t propose to understand what he wants, especially the 2001 version of him. But I think that there is a certain opinion that I could imagine these young people in 2001 who were following his message were vocalizing and maybe what their taste might have been at the time.

MARCUS: Were you one of those young people in 2001?

DA CORTE: I think I wanted to be because I thought that was something that would help me fit in and I wasn’t that at all, I was the opposite of that. I was a young, not quite out of the closet, Hispanic man. I didn’t understand what it was like to be blonde, straight and this ferocious person with power. And I think that as we can see now, you know, with the current political state of the world, getting as much power as one can get isn’t always a good thing. There’s real drawbacks to that kind of ego-driven way of living. So I think it’s a little bit about that and so Badland—the area of Philadelphia that my studio and my home is in is called Badlands—I think when I take photos of these poetic little occurrences that happen in the street and in the neighborhood, it’s my way of kind of finding something beautiful and magical in a place that would otherwise be considered troubled.

For me, much of my work is about redefining what good or bad is or trying to understand what makes people think something good, what makes them think bad, what makes something get lots of likes or not lots of likes. Is a donut better because it has the branding of the word Hoagiefest on it? Because hoagies are good and donuts are good so putting them together makes them better? Are two girls with pink cowboy hats better than one?

MARCUS: I guess that’s kind of the idea that would be implied by constantly searching for a crown, would just be to add more and more.

DA CORTE: Yeah like what kind of feeling do you have when you get a lot of likes [on Instagram], like who cares? Like to me it seems like that’s a strange pursuit.

MARCUS: What’s this drawing on someone’s back of people having sex?

DA CORTE: It’s a drawing on someone’s back of people having sex.

MARCUS: Did you do it?

DA CORTE: Yeah. [laughs] The person I was drawing on didn’t know what I was drawing, so it was funnier.

MARCUS: When you were taking these images, how conscious were these narratives of Eminem or the crown? Or was it something you noticed after you had taken them, these patterns emerging?

DA CORTE: I think that the patterns just emerged. After you take hundreds and hundreds of pictures, you’re like, “Oh, maybe this is something that’s guiding this.” But I was thinking about baseball hats and the fetish of sneakers and the fetish of lids and that kind of thing. But that’s not applicable to all the images, this idea of Eminem. It’s pictures of other stuff around me. We understand ourselves through the pictures we take because they act like a mirror to our lives and they make our lives feel like part of a movie. You know, a string of still images back to back make an animation.

MARCUS: It only makes sense as a linear narrative if you’re the person who took them.

DA CORTE: Even I don’t know, necessarily, when each photo was taken per se. But I could kind of ricochet around whatever that world was that I was taking, and then my mental state and think, this cementation of all these different parts equals, maybe, what I think a Badland is.