Arthur Jafa and the Future of Black Cinema

Cinematographer Arthur Jafa has made moving images for the last 30 years; there’s Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991), Spike Lee‘s Crooklyn (1994), and, more recently, his “light touch” as the director of photography for Solange‘s “Don’t Touch My Hair” and “Cranes In The Sky” music videos—all of which examine the interior lives of black Americans. His latest work, one entirely his own, continues in the same vein by vividly and viscerally tracking the experience of being African American. Titled Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, the seven-minute video contains found footage of black sorrow and success, all set to Kanye West‘s “Ultralight Beam.” It illustrates the ways in which racism has altered the lives of black folks, both personally and collectively.

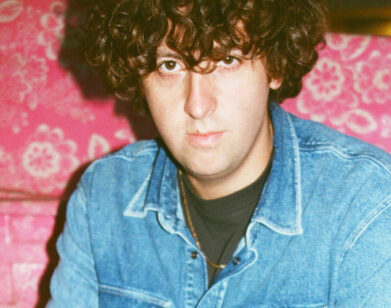

Just before the New Year began, we spoke with Jafa about the film—which is currently on view at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in New York—and what it means to make black cinema.

ANTWAUN SARGENT: What inspired Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death?

ARTHUR JAFA: That’s a hard question to answer. It wasn’t any sort of direct response to Trump and all this kind of stuff. I’m always making things, and I have this ongoing practice of compiling stuff that strikes me. Over the course of my life doing this, I’ve trained myself to do the opposite of what’s human nature, and that is to recoil from things I don’t like. Over the last few years of doing this, I’ve pushed myself to push toward things that disturb me. I’ve developed a habit of recording these things because these things often disappear. I’ve promised myself that I’ll try to record the spiritual quality of the things that strike me. To a certain degree Love Is The Message grew out of [this] practice.

SARGENT: How did you organize the imagery?

JAFA: The things sort of organize themselves naturally. One of my friends said in an interview recently that fundamentally what he’s trying to do is to put things in an affective proximity to one another, and I think that really crystallizes it. When you are talking about a mediated thing, a picture or representational image, it’s not “for real.” It always functions in this space of a sign or signifier. These things tend to resonate in a specific way, but what happens is when you place a resonant artifact next to another resonant object, they create a new harmonic. So at a certain point I had a set of images that resonated in response to one another. And like a strand of pearls, I just laid them out. Then I watched it and said, “Oh, this is kind of interesting,” and made a few adjustments.

SARGENT: How long did it take you to make Love?

JAFA: I would say 85 percent of it was done in two hours.

SARGENT: Really?

JAFA: Then, a few days later I happened to be looking at television and Saturday Night Live came on, and Kanye came out and he was performing “Ultralight Beam,” and I was like, “Wow, that’s a really amazing song.” Then I downloaded the live performance, and maybe a few days after that I laid the music down on top of it, and I was like, “Wow—really interesting.” There were gaps in the piece where I felt like the images were at best just treading water; they weren’t really pushing the piece forward. So I tweaked it and closed the gaps around the landmarks. Like the sister who gets pulled over and tells the cops you are terrorizing my kids, that was a landmark moment in the film.

SARGENT: The film is tough to watch because it shows how black suffering and creativity are bound together. What was your reaction to Love the first time you watched it in full?

JAFA: I gave Kahlil [Joseph] a really early cut, prior to putting in his brother Noah [Davis] who passed away, and he was really obsessed with it in a sense. He said it was really volatile. When I first put it together, I cried, then I never cried again. I don’t feel anything actually. It’s disturbing. When I look at it now, I’m sort of dead inside.

SARGENT: What made you cry?

JAFA: These are verifications of what black people know to be true about our status in society, positive and negative. I remember when someone told me phones were going to have cameras on them, and I thought that was the dumbest idea I’d ever heard. Why would you want a camera on your phone? But as we see the impact of it, it has allowed for a mass verification of what black people have been saying.

SARGENT: The Walter Scott scene was probably the hardest for me to watch soundtracked to “Ultralight Beam.” West in that moment is saying, “We on an ultralight beam,” repeatedly as Scott is running away from a cop who shoots him from about 15-feet away. He crumbles to the ground. The whole thing shook me and my faith. The visual and music in constructing that moment seemed perfectly intentional.

JAFA: Well, a lot of it was instinctual, because it’s just more material for me; it’s not a group of images set to Kanye’s song. But the song is a masterpiece because it does something that’s almost impossible to do: where a person can actually take a given form, the gospel song, and create a synthesis of gospel and R&B, like a Ray Charles, into soul music. Kanye in that song basically made the first formal evolution of gospel music in about 100 years. Now, Kanye is a genius, but people just don’t like it because he calls himself a genius a little too often.

SARGENT: The film is as much about presenting a black history as it is about your vision of a black cinema.

JAFA: I have a very simple mantra and it’s this: I want to make black cinema with the power, beauty, and alienation of black music. That’s my big goal. The larger preoccupation is how do we force cinema to respond to the existential, political, and spiritual dimensions of who we are as a people. Music to me is a convenient marker of that. Music is the one space in which we [as black people] know we have totally actualized ourselves; even though we keep inventing shit we don’t ever have to write another song to contribute as magnificently as we already have. So a cinema like the music—that’s what Love Is the Message is trying to do.

SARGENT: That’s the message? To make cinema match the intensity of black music?

JAFA: For so long people have tried to tell me, “That’s interesting, that’s cool, that’s polemical!” And I’m like, “Man, I just have to show these motherfuckers.”

SARGENT: I think you showed that with your cinematography that dates back to Daughters of the Dust, Spike Lee’s Crooklyn, and Eyes Wide Shut.

JAFA: This [film] seems like this big arrival, but it’s what I’ve been working toward since I shot Daughters of the Dust. Daughters was the first film that I’d ever shot. At this point in my life, I’m not just at war with the fucked up images of black folks that have diminished us and society at large. Far back when I was doing talks around Daughters, I gave a talk at the New School, and this older white woman stood up and said, “When I see Daughters and I see the grandmother, I don’t see race. I don’t see color. I see my own grandmother.” She was actually being progressive, but I immediately said, “Yeah, that’s all cool and well, but how come you can’t see color and see your grandmother? How come those two things are mutually exclusive? How come you have to erase something we cannot erase—our color? How come you have to suspend that for you to be able to have a point of identification?”

The question is how come we can’t be as black as we are and still be universal? How come we have to refuse who we are in order for someone to be able to be able to identify with us? How come the audience can’t see themselves in that thing, whether or not it looks just like them or not? It’s what black people do because most of what we see are white people. It’s what women have developed the muscle to do because mostly what they see are men. It’s what gay people are able to do because mostly what they see is heteronormative stuff. It’s a muscle that everybody needs to develop: the ability to see themselves in someone else’s circumstances without having to paint that person white, make that person straight, or a man. How can you see yourself in the other? That’s what it really come down to—empathy. I’m trying to make my shit as black as possible and still have you deal with my humanity.

SARGENT: So what’s the problem with contemporary, cinematic representations of black folks?

JAFA: The problem with black cinema in it’s current form is on the one hand it is the only game in town; it’s a very structured set-up and it’s not conducive to get at the kinds of things I’m trying to portray using the cinematic apparatus to show black sociality and how it functions. Shit on Worldstar Hip Hop is way more interesting than 99.9 percent of the bullshit black filmmakers in Hollywood are doing. To me, not every black filmmaker who is making black films is trying to make black cinema.

The thing that’s great about Aretha Franklin, when you hear her, is not just her individual genius, but that she is working in a form that evolved from the expressions, desires, and pressures of what it means to be black. Part of it is just trying to get people to see these things—the footage is everywhere.

LOVE IS THE MESSAGE, THE MESSAGE IS DEATH IS ON VIEW AT GAVIN BROWN’S ENTERPRISE IN NEW YORK THROUGH JANUARY 28, 2017.