Art Basel Miami Beach Diary, Part 2

The great museums have always reflected the enthusiasm and taste of individual collectors. Often the connections are obvious, as in the case of the Whitney Museum of American Art founded on the collection of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney or the Guggenheim Museum founded by Solomon Guggenheim, but even the Metropolitan Museum of Art was created by wealthy collectors who wanted to share their visions. The Met’s original collection was the gift of a railroad man John Taylor Johnston. For New York’s Museum of Modern Art we have three New York society ladies to thank, Miss Lillie Bliss, Mrs. Cornelius Sullivan and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller.

Museums are still being built the old fashioned way, through the energy of serious individual collectors, and one of the best stories in contemporary art is the Rubell Family Collection, a wonderful museum in Miami created by a New York family, Donald and Mera Rubell, and their children, Jennifer and Jason. Don was an obstetrician, a successful one, but the principal source of the wealth that built the collection was the estate of Uncle Steve, the delightful character who, with Ian Schrager, created Studio 54. It’s fitting that a fortune based on an innovative creative concept that captured the imagination of a generation would be spent on art. Not a few of the artists in the Rubell collection spent time in that club, where artists like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat could be found regularly.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (Negro Sunshine), 2006; Malcom X, Sun, Frederick Douglass, Boy with Bubbles # 3 (version 2), 2001, courtesy Regen Projects and the Rubell Family Collection

Great collectors are there at the beginning and the Rubells were there, investigating and buying when the new wave of American artists arrived. Many of the artists in the collection were unheralded beginners when the Rubells bought their work. In the mid-nineties the family acquired a 45,000 square foot warehouse in an unglam Miami neighborhood that had been a storage facility for the Drug Enforcement Agency-think of all that Miami Vice-type stuff collected by Scarface types, then confiscated-and they converted it into an exhibition space, opened to the public in 1996.

The Rubell is always worth a visit, but during this year’s Art Basel it offered the best art show in town with a powerful exhibition titled “30 Americans,” a group show of African American artists including David Hammons, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kara Walker, Kehinde Wiley, Glenn Ligon, Gary Simmons, and Robert Colescott. This is an enormously gifted and accomplished group but it’s not just a group show of artists who happen to be black.

Glenn Ligon’s work stands out wherever it is-from the Rubells’ walls to the high-priced precincts of Art Basel’s Convention Center-even though the artist is spectacularly versatile. His work ranges from Warhol-like pop portraits to abstractions made with coal dust to neon signs to text works that look like Kosuth gone funky: He has no signature look, only a signature spirit. Ligon has a sort of perfect pitch that delivers beautifully realized ironies with exquisite tone and eloquent humor.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, One Million Yen, courtesy of the Rubell Family Collection; Rashid Johnson, I Who Have Nothing, 2008, courtesy of the artist, Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, and the Rubell Collection

The show’s three Basquiats included one masterpiece, One Million Yen, from 1982, his greatest year (and maybe the greatest year a single artist ever had). It’s all here-his invention of hoodoo pop art, joining sympathetic magic, New York City sarcasm, cut up cubism, cargo cult improvisation into a tour de force of personal conjuring.

Thirty-one-year-old Rashid Johnson is a spiritual descendent of Basquiat, combining a delicious humor with an elegant sense of African ritual and tradition. His assemblages, made with black wax, soap, wood and various objects, function as altars of pop aspiration and historical meditation, postulating a new polytheist pantheon based on a funk pantheon.

I happened to walk into the Rubell at the moment when a group photo of the artists in the exhibition was being taken. I couldn’t help but think of Art Kane’s iconic 1958 photograph of 57 jazz musicians gathered around a Harlem stoop, a group that included Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Thelonious Monk, Roy Eldridge, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Gene Krupa, Jo Jones, Mary Lou Williams, Sonny Rollins, Marian McPartland, Charles Mingus, Gerry Mulligan and many more. Yeah, Basquiat couldn’t make this scene, but neither could Charlie Parker, but their spirits were in the building, and this radiant show gives us a delightful and inspiring look at an extraordinarily underrated force in art.

It was the collision of European and African traditions that created the great modern art form jazz. That’s the same fusion, belated by circumstance, that’s at work here, creating a compellingly relevant visual art with great wit, profound insight, and spiritual authority. I find the work of this group extraordinarily powerful and remarkably cohesive in a world increasingly crowded with naughty, flippant, stunt-driven, flagrantly artistic art more concerned with being fashionable and edgy and appealing to speculation than with fomenting thought, advancing a significant agenda, or expressing a process of discovery.

The current recession, following a period of shameless egotism and unprecedented hog-wild speculation, was framed to a certain extent by a shift toward art made with detritus and impoverished materials: a sort of neo-arte povera reacting to the vulgarity of grandiose grandstanding made for the amusement and theoretical enrichment of the private-jet set. We saw it at the last Whitney Biennial and at the New Museum’s inaugural show “Unmonumental,” but “30 Americans” is a more cogent and authentic expression of that tendency. At a time when American art seems to risk losing its soul, it’s appropriate that a group of soul brothers and soul sisters has come together with an exhibition that doesn’t fail to demonstrate where it’s at.

I checked out Art Positions, Art Basel’s exhibition space set aside for young galleries located in a group of shipping containers right on the beach near the Convention Center. A few years ago this was a great place to discover young artists. Now the site has upgraded-there’s a restaurant in the center-and the atmosphere seems to have shifted somehow. It’s hard to say exactly what has changed but I found myself describing it, “like a funhouse. Without the fun.” Most of the containers are now given over to a single installation with less being, in this case, less. Mostly it seemed to be gallery-branding environments designed to wow the rubes into thinking, gee art sure is weird.

As I mentioned in the last installment, Art Basel is the main ring of the circus that occurs in Miami in the first week of December, but it’s just one of many “fairs” flogging artistic product to the art and design tourists who descend upon the city to shop for their dreams and identities.

Last year in Miami I went to SCOPE, a wandering market that goes from New York to Basel to the Hamptons to London to Miami. I may have been in a bad mood at that point, or I may have seen too much art for one day, but I swear I did not see one artwork that I fancied. Is that possible? I do think that the sheer multiplicity of fairs tends to create a sort of group identity that doesn’t need a curator to make it reflect a commonality. SCOPE is market-based and I suspect that you might characterize much of the work shown as derivative. You see lots of photos that remind you of Gursky, Crewdson, or Ruff. You see lots of computer-based paintings or paintings finished with a power sander. You see enough cutesy anime and manga animals to make you a cynical Gumby torturer.

But that didn’t stop me from checking out other fairs this time. As usual I visited NADA (New Art Dealers Association) and found it the most interesting spot in town. This is where you’ll find the smarter, smaller, younger galleries and where you’ll discover up and coming talent.

Tomo Gokita, Fashion Victim, 2008, courtesy ATM Gallery

This year I liked the drawings with poetry of a young artist named Barry Johnston at Overduin & Kite, a smart young gallery from Los Angeles. We haven’t seen much good poetry in a good picture since Rene Ricard. New York’s ATM Gallery exhibited some really strong paintings by a cat who’s big in Japan, Tomoo Gokita, who’s sort of the Fernand Leger of black and white. He seems to be wrapping up the history of modernism, from surrealism to abstract expressionism, in a striking monochromatic (or is it achromatic?) package.

Kim Light Gallery featured Case Simmons and Andrew Burke, whose work is collage by computer, but which transcends that tool in achieving results that would have wowed them back in the Summer of Love. Their highly detailed assemblages of clipped magazine art and the like are big and enormously detailed in that sort of Haight-Ashbury/Hieronymus Bosch mode that appeals to those under the influence of psychedelics, but can also be entertaining to those of us attempting to navigate the planet by logical and conventionally intuitive means. There is a nice humor to their cosmically-constructed mandalas and Eastern-tinged pop pantheons that recalls the great painter Mati Klarwein who did those Miles Davis and Santana album covers.

Simmons and Burke, Temple 7, 2007, Courtesy of Kim Light Galley; Crop of Mati Klarwein’s Anunciation from the cover of Santana’s Abraxas

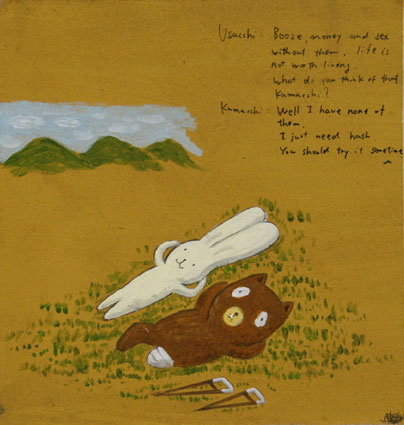

One nice feature of NADA is that you’ll find artists from places that are a bit off the beaten art path. Like Ireland. Last year I bought a little painting at the booth of Mother’s Tank Station. An almost tiny painting actually, which is a good size when you live in an apartment and the art world is filled with painters determined to make pictures for museums and/or the McMansions one finds in such places as the former potato fields of the Hamptons. How much longer can I wait for that Schnabel miniature? Anyway, the small painting I bought was from Atsushi Kaga, a young Japanese artist who lives in Dublin and seems to like the pub life as well as the herb favored by followers of Sellassie. His oeuvre is a sort of continuous comic strip featuring a cast of anime-style animals, particularly two friends, a bunny named Usacchi and a bear named Kamacchi who’s an amputee on crutches. These two are always in philosophical conversation, and so many of these paintings come the way I like ‘em-with dialogue. In the painting I bought, Kumacchi dunks a basketball standing on the shoulders of Usacchi, who stands on the back of a fellow in a masked marvel/batman kind of costume. Nothing needs to be said here. Usually I can’t tolerate anime or manga, but this work has such a refined sensibility that it’s simultaneously tender, philosophical and hilarious. I was pleased to see that the saga of the bear and the bunny has continued nicely. Usacchi has sprouted flowers from his ears. One of the nicest of Kaga’s new painting is a sort of bunny with still life entitled: “I always have flowers for you in my head.”

Atsushi Kaga, Usacchi and Kumacchi in July, 2008. Courtesy of Mother’s Tank Station

A recent trip proved to me that Dublin is a terrific place for an artist to work now, and Mother’s Tankstation has several painters (Kaga not among them,) working in a sort of flat, muted, post-Alex Katz style that is interesting in the lowness of its key.

A French dealer, Galerie Chez Valentin, had a piece I really wanted to buy-a pink resin sculpture exactly shaped like the classic Sony portable television, by Eric Baudart. I had to keep saying, “Pay for the pool, pay for the pool,” to restrain myself. Shane Campbell Gallery from Chicago had amusing works in charcoal on paper and oil on linen, from Jonas Wood, a Los Angels-based artist. The best were ancient Greek ceramics funkily drawn in black and white, complete with their B.C. dates. If the Greeks take everything back we’ll still have these.

At NADA the dealers tend to be very friendly, eager to talk about their artists and not too heavy on the sales pitch-and some of them are cute-but Mihai Nicodim was not that engaging. I assume that the person bearing that name was the rather gruff fellow sitting there. Maybe I caught him on a bad day. But I really liked some of the painters he was showing. Serban Savu, a thirty-year-old Romanian, makes soft-focus oil paintings that mostly show people working in rather humdrum occupations, baking, fishing, driving, but in a very dreamy atmosphere. They are very strong paintings, beautifully composed and with the courage to be quiet and reflective. This gallery also showed some very beautiful paintings of beekeepers working and rather fantastic landscapes. I think the artist’s name is John Stark but the gallerist scared me off. Next time I’m in L.A. I’ll going to work up the nerve to visit the gallery.

The Francesca Minini Gallery of Milan showed beautiful work by Paolo Chiasera, a formidable young artist from Bologna who reminds us that there is still intellect in an art world where the market has gone all Moloch on us, devouring beauty, nobility and good intentions.

Chiasera’s work is beautiful, but it’s not about the beautiful object, it’s about the process of enquiry into art and history and the nature of aesthetics. You can have a look at www.paolochiasera.org.

Oh, and I should mention Nicole Klagsbrun, a sort of underrated visionary among dealers who used to partner with Clarissa Dalrymple on the old Cable Gallery, which introduced half of today’s heavy hitter artists to New York society. Nicole is still selling the best artists, and while she might seem out of place at NADA when she would fit right in at the big show at the Convention Center, she looked great here, among the living. Nicole had a couple of nice Rashid Johnson’s hanging here, echoing 30 Americans, and she has a real thoroughbred “stable,” including Adam McEwen, Barney Kulok, Billy Sullivan, Stephen Mueller, Anderzej Zielinski and Dennis Hollingsworth, to name a few. Always a pleasure to see what Nicole has on hand.

I actually visited NADA and then went back two days later because I felt like I hadn’t seen everything. Not a good collector strategy. I wound up not buying anything. But that’s probably for the best. Anyway this is a place to make discoveries, and in a Net Jets art world this is a refreshing break from the tension and circumspect vulgarity of big time dealing and wheeling. It’s down to earth and arty. Why on the way out I even had to step over a poor artist who had wrapped herself up like a mummy in bandages and positioned herself on the floor so that she was inevitable, unless of course you did a U-turn and walked through the whole exhibition space again. I didn’t mind stepping over her. She was asking for it.

I may write another installment on Pulse or on the numerous parties I was forced to attend and the champagne I was forced to consume without a glass of water, on why I didn’t play paintball on Paul Sevigny’s team of artists at the Raleigh Hotel paintball game “Art War,” or on the brilliant stand-up comedy of Stuart Parr or the little-known wild side of the dealer Paul Kasmin, but not today. Time to make the doughnuts. But before I go I would share something I forgot. A Tracy Emin multiple stuck with me. It said, “Don’t look for revenge. It just happens.” The same could be said for art.