The Unseen Photos of Andy Warhol: Photo Booths, Bare Butts, and A Sewing Machine

Andrew Warhola, better known as Andy Warhol was, among several other things, a mysterious man. His delirious attraction to the glitz and the glam of fame and the gorgeousness of things gave life to his now world-celebrated art—which has been imitated, questioned, and, most reliably, celebrated. Everyone knows Warhol—consciously or unconsciously—whether they’re talking about his silkscreen prints of Hollywood luminaries, rock stars, and socialites like Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, and Mick Jagger, or simply debating the authenticity of his infamous hairdo. Warhol’s impact on art and culture at large can be traced tangibly throughout history. Exhibit A: this publication, which the artist founded in 1969 “as a way to get into movie premieres and other events to which he was not invited,” as the author Kenneth Goldsmith wrote in Giant Size. Warhol, through and through, was the first artist to treat his art as a way to get and sell things others didn’t have access to or simply didn’t need—influencers, as we’ve come to call them these days.

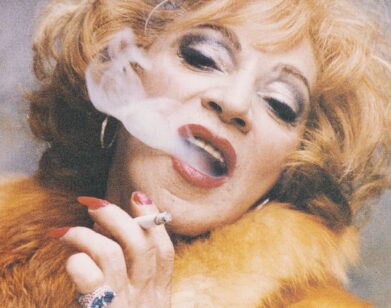

So when Chelsea’s Jack Shainman Gallery announced a “new major exhibition of Andy Warhol’s photography,” aptly titled Andy Warhol Photography: 1967-1987, it’s easy to wonder if there was anything new to see from Warhol’s oeuvre. But as Shainman himself explained during my visit to his gallery, the survey offers a rare opportunity to see “the evolution of Warhol’s photography” in the final three decades of his life, which includes the source material for some of his most well-known art pieces, like the iconic banana. (No, not that one.) After Warhol’s close friend Thomas Ammann, a Swiss art dealer, gifted him a 35mm Minox camera, the artist produced silver gelatin prints that he stitched together (literally) with a sewing machine. The only aspect of Warhol’s photographic practice to have a solo exhibition during his lifetime were these “stitched photos” in January 1987, six weeks before his death. From glamorous nightlife portraits to the explicit shots of his “Sex Parts” series—which together liken to a well-curated homoerotic Instagram grid—the exhibit reveals a truth about Warhol: The artist has always been ahead of his time, and seems to be ahead of ours, too. Below, James Hedges of Hedges Projects, who co-curated the exhibition with Shainman walks us through the exhibition, from his Times Square photo booth strips to his photographic celebrations of the male form.

———

ERNEST MACIAS: I’m curious as to why these photos aren’t as present in the Warhol discourse. When you do a Google search or speak to someone about Warhol, the first thing that comes to mind are his Marilyn Monroes, the Campbell’s soup, the Brillo box. So why are these photos now surfacing, and why should people pay attention?

JIM HEDGES: The stitched photos are the rarest out there. Warhol made approximately 500 stitch photos in his lifetime. They’re unique photo objects. He would take a picture with the 35 millimeter camera. They were always in panels of four, six, or nine. Nine is virtually never seen. The last show of Andy Warhol’s life was January, 1987 at the Robert Miller Gallery in the Fuller building and it was his big stitch photo show. That gallery show was meant to be the foundation of Warhol’s next big push with photography as his primary art form. The stitched photos were the cherry on the top of his career. They were his latest, newest, freshest thing. They have roots all the way back to photo booth strips and seriality and the machine interaction.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- Nude Male , c. 1977. © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

MACIAS: I was going to ask about Sex Parts. I know that he did the series, there were a lot of conversations around it, questioning if it was art or just porn.

- Torso, 1977. Polaroid.

- Torso, 1977. Polaroid.

- Body Builder (Keith Peterson). Polaroid.

HEDGES: There’s niche bodies of work in this space that I think are hugely important. This wall is called Sex Parts and Torsos, which are mostly gay male nudes—Sex Parts if it’s explicit, Torso if it’s classical in it’s look. You have a series of prints and paintings, of course, and works on paper, drawings that he made from these. This is a grid of 49. I once did a grid at the Grand Palais of 81 of these. When you get any of these Polaroids together, there becomes an abstraction that happens in the voids of space and how far the frames are away from each other that I think is really interesting. And then there’s Jean-Michel Basquiat in a jockstrap, which doesn’t feel like porn at all. In fact, what it feels like to me is more comical. Seriously. Look at the blow job pictures. They’re sort of fun. There’s something… so explicit. These classically inspired Polaroids [Torsos] are sort of endlessly rewarding. They’re hugely collectible. They’re $10,000. So relative to everything else, they’re very inexpensive and people get started and they buy one or they buy two and then all of a sudden I’ve got collectors that have 49 of them, 36 of them. That to me is super important. I personally love the Sex Parts and Torsos. I find them endlessly interesting.

MACIAS: How many did he take in total?

HEDGES: There’s not a number, but what I can tell you… When he took these sorts of Polaroids, the celebrity or portrait, like socialite pictures. He would usually take 25, 30 maybe 40 of them. But that’s it. So I actually had a photograph from the Factory. It showed Warhol and Debbie Harry reviewing all the photos, like just looking at them. I counted and there were 24 Debbie Harry Polaroids made. But, of course, each Polaroid is still unique.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

MACIAS: The collages with Jean Paul Gaultier I hadn’t seen before.

HEDGES: He was engaged as the artist to do a series of layouts in April 1983 or ’84 for French Vogue. Basically he was the editor of the magazine for that issue. And he did this series of collages.

MACIAS: [We approach the Polaroid Warhol took of Lee Radziwill.] I love the color in this photo. It is amazing.

HEDGES: It’s a super specific thing, isn’t it? Doesn’t that conjure absolutely a time and a place? I have another image of her that’s where she’s just a black sweater, and it’s super stark and super intense.

MACIAS: Instagram could never.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

———

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.