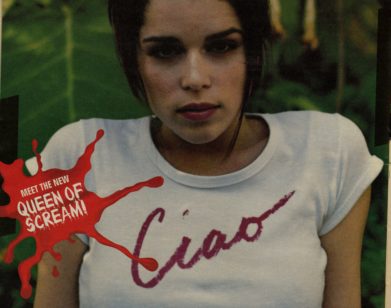

Alex Da Corte and Charlie Fox Are Into the Monster Next Door

When Halloween begins, Michael Myers is outside a house looking in. When Halloween begins, Alex Da Corte and Charlie Fox are looking at Michael Myers outside a house looking in. There’s something seductive about this overlap for both Da Corte and Fox, artists and writers who find common ground in the uncanny valleys of pop culture, both entranced by spaces in which audiences are as much a part of the thing they’re watching as it is apart from them. Da Corte, known for his surrealist reconstructions of myth and movies in his visual art, has conjured unseen threats with Hitchcockian precision (and a little help from frequent-collaborator Annie Clark, known to most as St. Vincent), in exhibitions with titles like C-A-T SPELLS MURDER. Likewise, Fox’s most recent work, My Head is a Haunted House, curates pieces that conjure the ephemeral anxiety of the suburban scaries. Both of them agree that in every fairytale story, it’s the monsters who are having the most fun.

Still, if Da Corte’s recent solo show at the Vienna Secession saw him surreally decked out as both Frankenstein’s monster and his bride, his conversation with Fox, along with Lucas Zwirner via the David Zwirner podcast Dialogues, has them both playing the doctor. Although they’re equally fascinated by bad guys, misfits, and freaks—as a kid, Fox put up posters of The American Werewolf in London mid-transformation; Da Corte painted a fresco of Disney villains on his bedroom wall—now, they’re building the creature, on top of admiring it. As they stitch horror, consumerism, and queerness together with everything from A Clockwork Orange to Meet the Parents, they show us that the thing they’re making is unexpectedly, exhilaratingly alive. — JADIE STILLWELL

———

LUCAS ZWIRNER: Charlie, you’ve been interested for a long time in a fantasy real, or at least in that kind of self-transformation. I’m curious how that began. Where does the monster interest come from?

CHARLIE FOX: Interest in monsters. That’s deep. I’m not even sure. I need to have a classy origin story here.

ZWIRNER: Or an un-classy one, actually.

FOX: When I was five or six, I would dress up like a vampire and have fake blood running down my face and stalk around in my parents’ back garden. I was fully devoted to this thing of being a vampire. Or looking at getting a werewolf mask and just sitting in my room, wearing that, and feeling really good.

ALEX DA CORTE: Was your family into horror movies?

FOX: No, I don’t think so. They didn’t discourage it. I was really into Disney as well, and I really liked the scary parts of Disney. I think that freaked my mom out a little bit. She saw that as a bit odd, to really be into Cruella de Vil. That was a figure.

ZWIRNER: I can relate to that.

DA CORTE: They’re the most fun, and they’re having the most fun.

FOX: They’re having fun. They’re apart from the normal world, you know what I mean? They’re these figures who are like, “Fuck you, I’m going to do this.” Like, Cruella de Vil and her amazing house with the dying trees that looks like something from a Roger Corman Poe film. I do remember re-watching the trailer for Edward Scissorhands on VHS so much that the tape wore out. I really like the thing of being scared by these people and being drawn to them at the same time. I knew that it was a kind of love that I was feeling for them that I didn’t get off regular characters. I wouldn’t get off to Hercules in the Disney film because he was just a hunk. I had problems, and still have problems with my body—physical ailments and conditions.

So I’ve always felt, even on some unconscious level … you know this certain world isn’t accessible to you. An ordinary world where you couldn’t maybe run really fast or know how to tie up your shoes, which is something I still don’t know how to do. My hands don’t work well enough for me to do that. It just precludes you from certain things, so you have to create your own royalty and fall in love with these other figures. Every time I see the devil from Fantasia, or I see Boris Karloff as Frankenstein, my heart throbs in a delicious and disturbing way. I like that feeling.

ZWIRNER: How I came to discover your guys’ friendship was this piece that you wrote about Frankenstein and about slow graffiti in the New York Times style magazine. You talked a lot about how there’s something about queerness in that Frankenstein character, and there’s something about intense romance and tragedy that’s being captured. Maybe even, in a larger sense, that could be identified with a character like that.

FOX: I mean, there’s a great tradition of that. There’s a long history of there being these other families. I mean, The Addams Family, or The Munsters, or—to give a trashy example—Diane Arbus. I mean, I shouldn’t badmouth The Munsters. Diane Arbus and John Waters’s films are all about these other families and these misfits that can all live together in a world which is apart and separate from the tyranny of normality, the tyranny of good taste.

DA CORTE: Paris is Burning.

FOX: Yes, Paris is Burning.

ZWIRNER: Alex, so much of your work, I feel, is also creating these other realities where things don’t work, even the objects that we recognize. I remember being in your studio and seeing these benches. The bench has a light on it, the bench is not to be sat on, and the world is not colored the way we typically expect worlds to be colored. Are you aware of constructing this totally other real, or wanting to inhabit it when you make the work?

DA CORTE: I think if you have ever been marginalized, you get used to living on the periphery and understanding how this center, how the normative behavior works—how it functions. You recognize that that function isn’t for you, and how the best thing that one can do if they have ever been marginalized is to accept that difference and not even try to level it, just relish in the dysfunction. I don’t see a chair with a light on it as absurd or un-normal or against the standard. I think of it as just a hopeful proposition for what is my reality.

ZWIRNER: How do you cultivate, I would even say, the strength to stay the course? I think that is what is so powerful about the show that you’ve curated at Sadie Cole or your book, This Young Monster, this consistent vision for something else.

FOX: It’s good if it makes the regular people nervous. Or even if it makes them realize that the idea of being normal is like a flimsy hologram. There are bats in everybody’s attic, that’s the truth. It’s nice to draw people into this world, and make it very seductive and delicious, even if some of the stuff in there is disturbing. I think it’s all beautiful. It’s just maybe not a kind of traditional beauty that people are fed—it’s a kind of analgesic beauty. The thing I hate most of all is just being in the world in a sort of numb way. I’m trying to make these delicious, kind of perverse worlds where these weird creatures can come out and play. I don’t feel at home in the world very much. Walking down the street—it can be a really hideous experience. So I wanted to make a place where I could be at home.

FOX: I hate stuff that’s clinical or designed to withhold pleasure. Enough things exist in the world to—

ZWIRNER: Withhold.

FOX: Yeah, which don’t give me pleasure, or I find torturous, or boring or whatever.

ZWIRNER: What would be some of those things?

FOX: Oh, man. There’s so many. Cars. Just looking at a car is just depressing to me. Cars, cheese.

DA CORTE: You don’t like cheese?

FOX: I don’t. I hate cheese.

DA CORTE: You hate cheese?

FOX: Yeah, I hate cheese.

DA CORTE: Oh, man. I don’t know if we can be friends.

FOX: I know, and I know that I’m missing out on a whole galaxy of pleasure. I hate the word, I hate the color. I hate banks. So many things. I don’t have a considered list of hates. I hate things that are just designed to be numbing agents. Fuck all these things that don’t give me pleasure. I really want to do something that is almost like a drug, like a drugged reality, a heightened hallucination of the world—of a world that doesn’t exist so that you have to make it real, so you can live inside it and feel good in there.

DA CORTE: Even with the propositions of spaces that are seductive or psychedelic, there can be critique. There’s ways to pull you in and then to zap you. For me, to present a space that is actually really garish, or really over-saturated or overly saccharine is the only way to say maybe your taste isn’t what you thought. Or to privilege bad taste. That’s what John Waters does. It’s a sort of embrace of the things that are taboo or the things that scare you because, what is a world that keeps out taboos or things that scare you? To me, that’s a really boring fucking world.

ZWIRNER: Is there an erotics to the monster world?

FOX: I mean, I’m obviously going to say yes.

ZWIRNER: But how does it manifest, right? Because that’s the most far away from the normative world—the idea that monsters would be not only interesting and lovable that we can empathize with, but actually attractive in some way.

FOX: Yeah, like the Beast in Beauty and the Beast, the original version and the Disney version. He’s hot. You know it and she knows it too. And the tragedy of that film is when he reverts back to being just a white, blonde dude. It’s a thing of huge sorrow to me still. When I was a child and I would watch it, I would be very distressed by that ending. I was like, why can’t she just marry the Beast? She spends all the time falling in love with the Beast. And then for that to be taken away, it’s just cruel and unusual.

DA CORTE: Charlie, did I ever tell you about how I had all of the Disney villains painted on my bedroom wall?

FOX: No. Oh, man.

DA CORTE: When I was 10, 11, 12—it went on for years. It was my version of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, but it was just the Disney villains painted in my bedroom. The one outlier that never made sense to me was that I painted the Beast on the wall. People would say, “He’s not the villain.” And I thought, but he kind of is sometimes. He’s just not constantly the villain, but maybe he’s sometimes the villain. That was sexy and attractive, to surround yourself with these flamboyant baddies.

FOX: Like Edward Scissorhands, which is again, another mutation of that same tale, is about an artist. On one level, he’s there making art for the family or for this suburb. And then there’s the great moment where the redhead housewife who’s trying to bang all the mechanics comes down. She’s looking at him, all smoldering Johnny Depp, cutting this dog’s fur or whatever. She goes, “Oh, he’s a perversion of nature. Isn’t that exciting?” Like, yes. That woman knows what’s up.

Often the things that I’m drawn to are things that at first, I’ll be like, holy shit. What is that? It really kind of freaks me out, or I don’t like it, or I feel like it’s wrong or tasteless. And then I go towards those things and try and eat them up because I know that really, it’s the first shock of love.

FOX: You can hear the 80s drums just pounding.

DA CORTE: The shock of love.

FOX: I wish I’d had the Disney villains on my bedroom wall. All I had was Jack Nicholson as the Joker.

ZWIRNER: What were sources of erotic excitement early on, in developing sexuality? Because I think there’s a real acceptance of what was exciting to each of you or what continues to be exciting to each of you. I feel it in the work in a way. Sometimes when I look at your videos, I think that there’s something about what you’re doing which is sort of exciting to you to watch, and exciting to us. And I think especially interesting when you’re a straight white guy to watch the video and be like, there’s something really exciting here and I don’t know how to access it necessarily, but I can absolutely feel it. I can feel it pulling me in.

FOX: In a way, when you’re a child, all the excitements come together in one sort of delicious ooze. There may have been things that I was getting off on in a way that I can no longer achieve. There was something about that that was overpowering. Like chocolate in a sandwich.

ZWIRNER: Oh, like Nutella or something like that?

FOX: Yeah, yeah, that stuff. Or certain flowers. I had a secret thing I was really into as a child, which was this thing that Homer Simpson does, to pretend flowers were food and just eat them randomly. So I probably was erotically drawn to flowers.

ZWIRNER: For most of us, there’s a very clear division between what you’re interested in and what’s arousing. For you guys, it seems actually pretty fluid. It’s like interest can become directed in a different way.

DA CORTE: If I think about the movie Halloween, I think about Jamie Lee Curtis. And as a young gay man watching that film, I wasn’t attracted to Jamie Lee, but I was attracted to the idea that someone would want me that much that they would want to come and kill me. Or that they’d want to follow me to the end of time. She had that kind of appeal—to be desired by someone else that’s maybe a monster too.

FOX: The werewolf in An American Werewolf in London. I also had him on my wall—a picture of him mid-transformation, screaming. That was really attractive to me. The Beast. I didn’t really understand why I was drawn to these figures. It took me a long time to figure out why that might be, but I really loved them.

ZWIRNER: But it’s not gendered really, right?

FOX: No, no.

DA CORTE: No.

ZWIRNER: It’s really more about the Beast and less about it being a male beast or a female.

DA CORTE: But it’s interesting for something like, say, the cartoon character from The Lion King, Scar. I was really into Scar. I thought he was just a cool and seductive figure. But going forward, you find out that the animator who made it was also queer.

ZWIRNER: I had no idea.

DA CORTE: Andreas Deja. And here, he’s kind of putting himself in this figure. All of the characters that I was finding myself attracted to were people of his making. Then you kind of realize, oh, I’m folded up into kind of path towards a fantasy that we might share in common.

ZWIRNER: Charlie talked a little bit about his childhood or at least aspects of it. And I was curious, Alex, what the world was like for you growing up? You talked about how one of your parents is Venezuelan?

DA CORTE: My father is. My mother’s from New Jersey. Growing up in Caracas, Venezuela, to be totally displaced, and to not speak the language and then learn the language. And then to come back to a place where now you’ve developed a language separate from the spoken language of the town, and to feel like an outsider again, totally kept me on my toes. It totally kept me wondering, where is my place? What is my race? Who are my people? Who is similar to me that I can relate to?

ZWIRNER: Have you found that at all? Do you feel like there’s a set of people or a number of people that make you feel most comfortable?

DA CORTE: Yeah, I have my Paris is Burning. I have my Philadelphia’s burning. And that’s where I stay. That’s where all of my garden is, and I’m happy to be a part of that garden. But it took some time to not feel alone or not feel like an outsider.

ZWIRNER: That’s a little bit the premise of this—the idea that the monster as a character is more and more someone that is in our psyches in some way. Your interest has obviously been there forever. It’s deep, and it’s personal. But at what point did you realize, oh, shit, actually, this thing that I’ve been interested in for a long time is actually getting attention?

FOX: I was 23 or 24, and I was at home watching Alex DeLarge’s shot by shot remake of A Clockwork Orange. There’s the line when Malcolm McDowell goes home, and he’s had his behavioral treatment and he’s been fixed, or supposedly fixed, by this aggressive therapy. There’s a lodger in his parent’s house, and he refers to Malcolm McDowell as “this young monster.” As soon as I heard those three words, I was like, oh, shit, that’s what my book will be about. I had no intention of writing a book at that point. I was just going out and smoking cigarettes and barking at ambulances or whatever I was doing.

I would say that I was a totally different person by the time the thing was finished because I had been through heavy things in my own body. Feeling huge alienation from my own body, and in some way, my own taste. I knew I was repressing a lot of things, maybe, before I started working on the book. And that perversity was there, that evil was still there inside me, that delicious evil. But the book fully allowed it to be like this bird, this thing that was then unleashed. The host body died and the monster—

ZWIRNER: Just came out?

FOX: Came out. The werewolf transformation had occurred.

ZWIRNER: I’m wondering if there was a similar moment for you, Alex. Because you also feel to me now, when I’m with you, that there’s no struggle to be anything other than you are. And that’s a simple thing to say, but it’s not true of many. I would say I’m there fully, but I think I’m drawn to people who seem to be there more. I think a lot of people are governed by fears about what would happen if they let those defenses down and just accepted whatever came.

DA CORTE: Yeah. I think that if you see death and real tragedy closely, it kind of shakes you. It reminds you that whatever hang-up you have, or whatever kind of feeling of difference that keeps you down, is to be put aside, because our time is limited. And to just own what you got. Just own it and rise above whatever fucking bullshit is being thrown your way. I’m largely attracted to fear as a language to operate in, to insist upon confronting the things that keep me in my place, maybe.

ZWIRNER: When you say it’s sort of a language for you, what would be an example of deploying fear?

DA CORTE: I’m a wallflower. This makes me scared. Leaving my house is hard for me. I feel agoraphobic on days. It’s a brave new world every day for me. My mind is kind of a wild place sometimes. So there’s a certain kind of insistence to have to confront it and go into the world, I think.

FOX: Anxiety is a big cauldron of stuff.

ZWIRNER: That you’re stewing?

FOX: Yeah, constantly. Anxiety is a kind of negative excitement, like a weird reverse, sort of bad lightening or whatever that happens inside you, in the same way that you get really excited about something.

ZWIRNER: A lot of great titles. “Bad lightening.”

FOX: That’s the name of my drug I’m going to do. Bad lightening. You have to snort it.

DA CORTE: Only take it if you’re Charlie.

FOX: The body can be devious and hideous and unfaithful to you, and not even work for you. Parts of my body still don’t work very well. Locking a door can cause anxiety. Going to the supermarket.

DA CORTE: There’s a culture of constant catering. You can get your food in an instant, you don’t have to wait, no more lines. Convenience, convenience. But there’s still this thing about the body that is material.

FOX: You can’t get away from it. You can’t get out of it. There are these ways to escape your own body, but ultimately, you’re always in it, this cage of meat.

ZWIRNER: “Meat cage.” Another great title.

DA CORTE: That’s a cool club, Meat Cage.

FOX: Meat Cage is, like, a night club where it’s very hardcore. Maybe Slayer is playing. Over the top, and there’s flames around the door.

ZWIRNER: It’s funny, I hadn’t thought about it. When your body’s working for you most of the time in a normal way, it’s not thematized for you with the same level of intensity.

FOX: I think that my body is hard to use and I have to acknowledge that all the time. I think that there’s some kind of idea, people assume that I’m getting off on this stuff in a nasty, snotty way or something. “Oh, look at these people who are hideous or whatever, or perverse.” Like it’s a sickly thrill for me or something. And that isn’t really the case. I feel a deep empathy.

Even the spider that’s at the haunted house show that Alex made, the spider being crushed by the huge boot that’s cowering. I know Alex hates spiders, so I shouldn’t bring this up and bring another anxiety into the meat cage threesome. But I feel empathy for the spider getting crushed. Or when I look at the Diane Arbus kid with the clawed hand holding the hand grenade, I totally understand what’s going on in that kid’s head. I don’t look at it and think, oh, that’s strange.

ZWIRNER: The last thing I want to ask about is movies because both of you have a real deep love for movies of all kinds, horror in particular. You don’t typically watch movies where anyone like a Diane Arbus character is being represented in any way, right? I mean, that’s not the common experience of a moviegoer. How do you reconcile the fact that probably a lot of the movies that you’re watching, even that you like, have nothing to do with exploring that?

DA CORTE: Maybe more and more you do.

FOX: I can tell you what my favorite example of that is recently. I was really hungover and watching Meet the Parents for the thousandth time. There’s an incredible moment when they’re playing volleyball in the pool at Owen Wilson’s house. And Ben Stiller spikes the volleyball and breaks his sister-in-law’s nose with this huge spiked ball. And then the whole family dives over to save his sister-in-law, and his mother jumps in the pool. Ben Stiller is left on the other side of this net with the whole family around, and he’s desperate and heartbroken.

And then Robert De Niro turns, and it’s a first person shot. He looks at Ben Stiller, but he’s looking at you, and he does this repulsed face. That’s an amazing thing to be confronted. That’s some kind of Kafka-level horrific nightmare. The father looking at you, horrified, like, “you grotesque thing.” And you’re forced into the position of this fool.

And then I was doing some background research on it. The director said, “That movie’s not a comedy. That movie is an anxiety dream that you’re watching. It’s a romance set within an anxiety dream.” All of the set pieces are all weird. There’s shit everywhere, there’s a cat pissing on some ashes or whatever. They’re completely horrific, anxiety making, nightmarish set pieces that all just follow sequentially. It’s like being in the sweatiest, darkest fever dream. That’s wonderful to me, to see stuff like that going on. These little moments of mainstream entertainment giving you something really creepy.

DA CORTE: The joy of watching movies for me has always been about that. That screen offers you this place to escape, but it also reminds you that that place is made from the physical space that you’re in too. There’s the bridge. Whatever’s happening in the film, that capacity is here and now too. It’s within in my reach. You can actually meet that vision halfway. Or more than halfway.