How Richard Hamilton Went Pop

To speak with Alan Cristea is to enter a world of high art and cynicism in equal measure. Renowned as London’s “print man,” distributing rare illustrations across the world from Picasso to Jim Dine, it was this love that led Cristea to Richard Hamilton, the 20th century’s most continually dynamic visual artist. A fan of Hamilton’s work since his days as an art-history student at Cambridge University, Alan tracked down the artist for a business lunch, and the rest is art history. From their first meeting in the early 1970s, Hamilton and Cristea formed a strong friendship—working together, holidaying abroad, collaborating, and arguing a fair bit along the way.

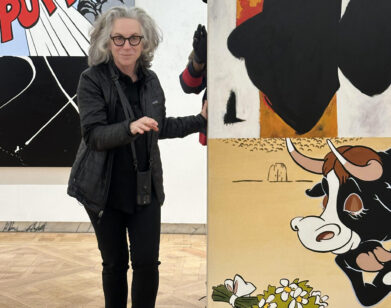

Since Hamilton’s death in 2011, Cristea has acted as distributor of Richard’s artistic estate. With intimate knowledge that spans Hamilton’s entire career and personal life, Cristea was asked to consult on the upcoming Tate Modern retrospective of Richard Hamilton’s work, its biggest ever to date. Cristea’s own gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Arts also pay tribute to Richard in two landmark shows on his installations and early print work. Days before the exhibitions were unveiled, we spent a morning in Cristea’s gallery, discussing Hamilton’s most niche work, his thoughts on celebrity, and that much-talked-about status as the godfather of Pop Art.

GRACE BANKS: Richard seems to be receiving the retrospective treatment en masse this year…

ALAN CRISTEA: Yes, it’s all sort of culminated rather quickly. The Tate Modern show is the biggest retrospective of his work to date, I think it will be very good. They have a lot of prints in the show, early as well as late. It’ll be a real tour de force of Richard’s work. I’ve worked with the curators at Tate on their show, purely because I knew Richard for such a long time. I’m very familiar with his work, so I can provide that angle. But Rita Donagh, Richard’s widow, should be attributed too. She’s a wonderful artist in her own right, and she’s the most angelic person. There’s one catalogue that covers all the exhibitions, so the Institute of Contemporary Arts, the Tate, and my show, which will focus solely on prints.

BANKS: And that’s how you met Richard, isn’t it?

CRISTEA: Yes, I’d been a fan of Richard’s prints for ages, since I was studying at Cambridge. At the time I met him, I was working at Waddington Galleries round the corner in Mayfair, which at the time was the biggest gallery in London. It was 1972, and I kept pestering Lesley Waddington to see Richard Hamilton. He didn’t like Richard’s work, but I kind of persuaded him to at least meet with this guy. So we went to meet him. It was a pretty memorable moment. Richard was living in Highgate, and when we knocked on the door Lesley, who had never met Richard, immediately said, “Now, Alan’s the only reason I’m here because I’ve never much liked your work.” Richard, who always had a great sense of humor, just cracked up. He thought it was so funny.

BANKS: Good that he had a sense of humor, then…

CRISTEA: Yes, exactly. So that was the first meeting, just the three of us at his house. And of course I went on to become the sole distributor of all his prints. But really, more than anything else, I simply loved Richard to bits, we had such a great time together. You know we went on holiday together, he frightened the life out of my with his speedboat… Yeah, I loved him. He didn’t think of me as some stuffy intellectual guy. He thought of me as a nice bloke he could introduce to his friends who didn’t cheat him. Since we met we worked together and didn’t stop until he died.

BANKS: So you had admired his work from a distance since art school?

CRISTEA: Very much so. I had done history of art at Cambridge. Obviously at that age, like all young people were, I was into the contemporary, and Richard was such a guru figure in the movement. If I was going to work with anyone, it was going to be Richard.

BANKS: Was your friendship collaborative in terms of work?

CRISTEA: Yes and no. Richard was extremely confident, he really knew his mind when he was creating his art. But we always collaborated on exhibitions, whether they were at my gallery or elsewhere. He’d ask me to write the introductory essay in every catalogue that was produced for his shows and he’d always be saying after he read it, “Change this and that.”

BANKS: So he was very hands-on?

CRISTEA: He was totally controlling! The only catalogue he didn’t control was the one he hated the most.

BANKS: He must have trusted your judgment…

CRISTEA: Something like that, yes. One of my fondest memories of Richard is from a party in the late ’70s or something. We were chatting with another dealer—and bear in mind, Richard did not like dealers at all—and this man was asking us about Richard’s prints and how my involvement worked with distribution, and Richard turned around and said, “But I don’t consider Alan to be a dealer, I consider him to be a friend.” It was one of the most touching things he ever said. And indeed, with his paintings, he would go out of his way to avoid them landing in the hands of dealers, the only way he could do that was to sell them to museums.

BANKS: That’s very socialist of him. Was he worried that his work would be misrepresented in the hands of dealers?

CRISTEA: Well yes, he was going on the basic socialist premise that dealers were there to make money, they weren’t there to appreciate the art. He felt that if he sold to a private person they inevitably resold the work, if he sold them directly to dealers he was just putting them in the hands of the profit makers, and he preferred for them to go to museums. He had very close relationships with certain museums, he certainly had a very close relationship with the Tate, who own a lot of Richard’s work. In fact, the retrospective they’re putting on is the fourth they’ve run of his.

BANKS: A lot of people going to see this Tate show will associate Richard with Pop Art. How did Richard see himself within that movement?

CRISTEA: Yes, it’s the most interesting subject for most people because I suppose that was the height of his engagement with the contemporary, and his work has so much to do with how news is mediated. I mean he did actually coin the term Pop Art in a letter for “This Is Tomorrow,” at The Whitechapel Gallery in 1956, he did the famous collage, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing, which was in fact a prep collage for the poster for the exhibition of the show. It achieved this iconic status because of the man holding the lollipop, which said Pop. I think the whole thing Richard was trying to get at with Pop is that it’s an abbreviation for popular. In the letter he wrote for “This Is Tomorrow,” he characterized Pop Art as transient, witty, sexy, big-business, short-term, money—you know, Pop! But I don’t think Richard himself was ever a real fan of the popular. What Richard was most interested in is the way that society was developing, and the role of the media, big business and advertising, and what effect that had on human nature.

BANKS: Right, and he kind of stepped away from that scene.

CRISTEA: Oh totally. When you say Pop artists people think Warhol, Lichtenstein, they don’t think of Richard at all! I mean as Richard’s distributor people are always coming to me and asking for the same thing. My Marilyn, or Swingeing London, and there’s so much else to him. But at the same time, he is this big figure in Pop Art and also he was largely responsible for drawing attention to the next generation of people. Because Hockney, Allen Jones, Peter Blake, all those people he was older than.

BANKS: At the time celebrity was intrinsic to Pop Art, what did Richard make of fame?

CRISTEA: He could take it or leave it. I mean, he was hanging out with The Beatles at one point, and he became friends with them, yes. By that stage Peter Blake had already done Sgt. Pepper, and you could not get more extravagant than that cover. It was just this collage of everything. So when it came to the next album, Richard wanted to do the opposite. And to be honest, Paul was a bit worried about that, and the compromise was the insert in which there’s this collage of photos of them all. That album wasn’t officially called the White Album. Officially I think that it’s actually called The Beatles, but everybody knows it as the White Album, because everybody knows it as such a cool, hip modern thing. It’s a reflection of Richard’s self-confidence, he wasn’t nervous about it at all. They were!

BANKS: What did he think of the American Pop artists?

CRISTEA: He was intrigued more than anything by people like Warhol as a social phenomenon. Frankly Warhol was and is big business, you put a Warhol show on and loads of people are going to come and see it. But people treat him as a social phenomenon, as someone who had a huge effect on society. And Warhol was in love with celebrity, he loved associating with fame, and because he was a rather weak human being, that meant that he understood other weak human beings; and one of his weaknesses was a love of celebrity. If they want Marilyn Monroe, give them Marilyn Monroe. Which is the total opposite of Richard. I mean people were actually writing to Andy Warhol and saying, can you do me a series of the four reigning queens, or the most important Jews of the century, or cowboys and Indians. Whereas Richard never did anything anybody else asked him.

BANKS: I love this thought of Richard as an artist set in his ways. What did he make of British art in the ’90s?

CRISTEA: He wasn’t very impressed. Damien Hirst was a big fan of Richard’s, kept sending him his work. But I do remember there was an evening, an opening of Richard’s at the Gagosian in London. There was this big dinner after and he actually stood up and said, “Why is Damien Hirst here? He’s such a crap artist, I didn’t invite him.”

BANKS: And Damien heard?

CRISTEA: Damien was there, his manager was there! He could be very mean. I remember visiting the British Pavilion with him when Tracey Emin was showing, and he was literally crying with laughter because he thought it was so second-rate. And he had such convictions about things that he wasn’t affected by what was fashionable. I mean he was literally looking at it saying, “There is no redeeming feature here.” But he had his fondnesses, too.

BANKS: Duchamp, for one…

CRISTEA: Completely. It took Richard 25 years to get to the bottom of Marcel Duchamp, and it came to the stage when Duchamp said, “Okay, I think you do actually understand me better than I understand myself,” and it was a great moment.

“RICHARD HAMILTON” RUNS FEBRUARY 13 THROUGH MAY 26 AT THE TATE MODERN. “RICHARD HAMILTON: WORD AND IMAGE” RUNS FEBRUARY 14 THROUGH MARCH 22 AT ALAN CRISTEA GALLERY. “RICHARD HAMILTON” IS AT THE ICA FEBRUARY 12 THROUGH APRIL 6.