OPENING

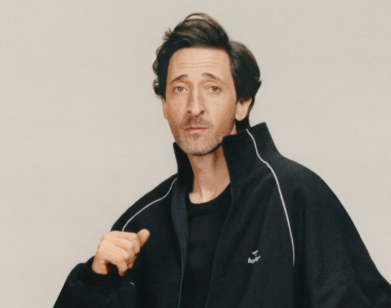

Adrien Brody Wants You to Know He’s Serious About His Art

All photos by Emily Sandstrom.

WEDNESDAY 6:55 PM MAY 28, 2025 2025 MIDTOWN EAST

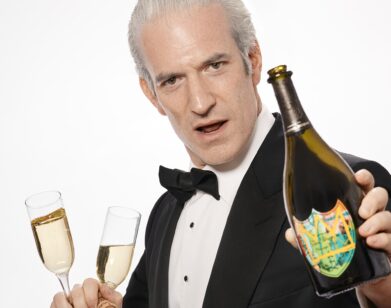

Why does Adrien Brody’s art look like… that? It’s the first question that springs to mind when you see what one of the most gifted actors of our generation has been busy painting. The art pouring out of the two-time Oscar winner floats brazenly in the part of the market cornered by the likes of KAWS and Banksy and collected by Cybertruck-NFT-manosphere inhabitants—a style that Wet Paint columnist Annie Armstrong identified as “Red Chip art” earlier this year. Scoff all you want, but there’s a real market for these works. Last week, in fact, at a gala held in Cannes, Brody unveiled a graphic, fragmented Marilyn Monroe on canvas. Meme’d, mocked, and ridiculed by unemployed X users, the work fetched a whopping $425,000 at auction that night. So the question becomes: who’s laughing now? I’m not totally sure, but on Wednesday night I journeyed uptown to EDEN Gallery, where Brody had installed his latest show, Made In America. Welcomed in by spitting rain, a mini red carpet, and A Tribe Called Quest rumbling on the speakers, I found a quiet moment away with the actor to talk about the influence his parents have had on his career, his New York City roots, and who he claims as his artistic forerunners.

———

EMILY SANDSTROM: First thing, congratulations.

BRODY: Thank you very much.

SANDSTROM: What conversations do you feel like your art generates?

BRODY: I don’t know. I mean, I hope they open any conversation, but it’s been an internal dialogue for a long time. It’s been a processing of all of the influences that we have in our culture and of the many influences that I’ve had growing up as a New Yorker living in Queens and being the son of an artist. And then the influence of my surroundings, my music culture, the streets of New York, my friends and kind of urban environment and it speaks to lots of things. It’s kind of an unpeeling of the layers and almost a nostalgia for another time. But how, as a man, I can reflect on the influences of my youth and how they’ve shaped the man that I am today.

SANDSTROM: Who are some art world legends that have really influenced you, and who do you feel like you work in the style of?

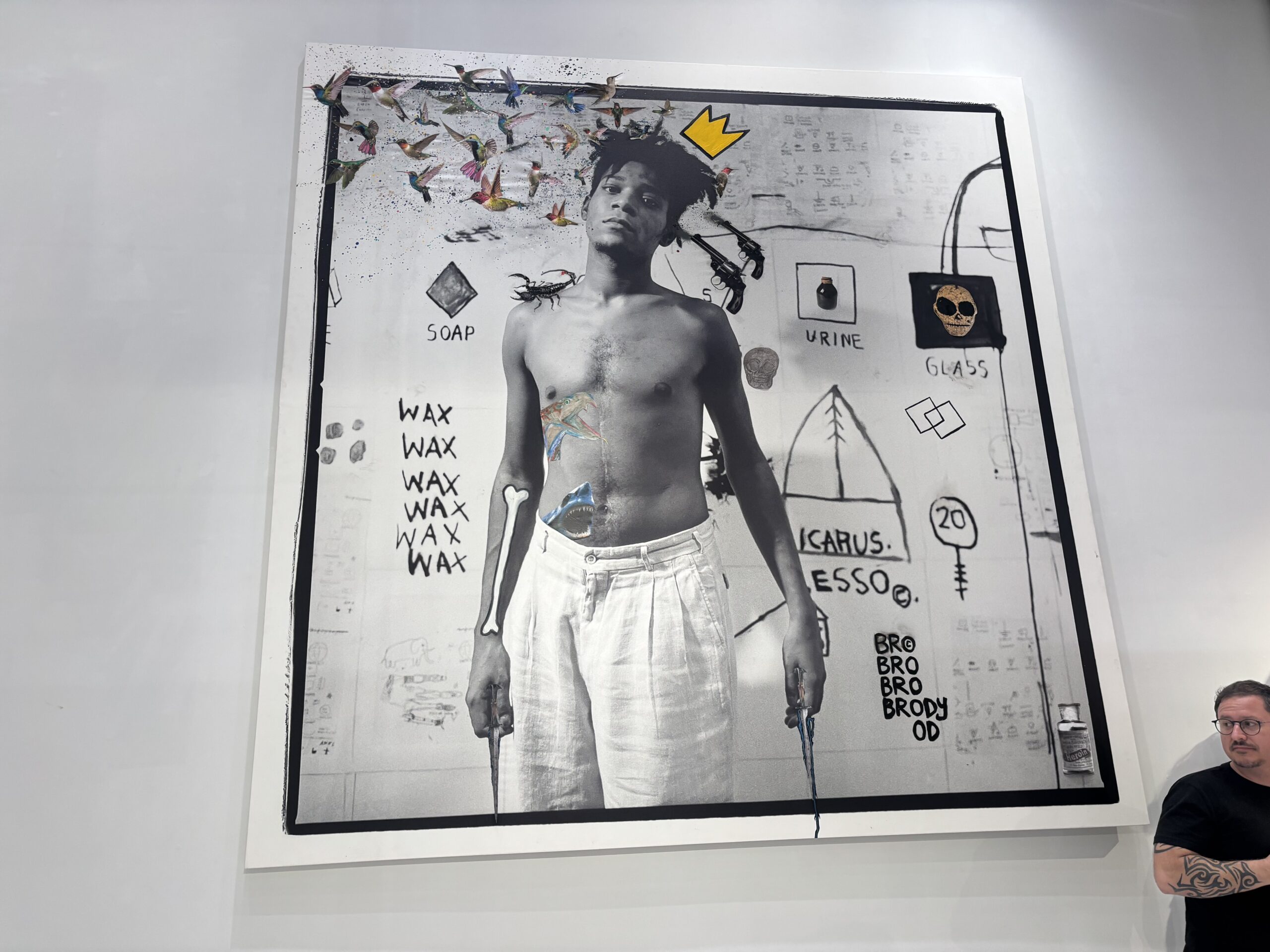

BRODY: It’s not that I would say, oh, “I noticed you make movies that [Robert] De Niro might make.” It’s like I find inspiration in greatness, but I try not for my work to be derivative of that. We’re influenced clearly, and sometimes it’s a play on those things. I mean the Basquiat piece, for instance, is a work of my mother’s when she was on assignment and photographed him at his studios. That’s her photograph.

SANDSTROM: Cool.

BRODY: So it is an opportunity for my mother, who’s my greatest influence and inspiration as an artist, to inform my work and give me a guideline. And then for me to work in addition to an artist that I greatly admire, and weaving in elements that I feel into not only his piece that he’s standing in front of, but kind of his demise, which is from an overabundance of creativity and need for expression and also the influences and circumstances in his life that ruled his existence.

SANDSTROM: How do you find time to work and where’s your studio?

BRODY: There were years that I was pretty much putting down acting and looking to paint primarily. Whether I was showing or selling works, I just wanted to paint. I find great creative autonomy and freedom in creating tangible, visual art as opposed to interpreting the words of others, and then having that reinterpreted through other creative minds–an editor, producer, director, et cetera, and being reliant upon that whole machine to do creative work. Drawing and painting has preceded acting. Since I was a child I’ve been painting.

SANDSTROM: I think it can be tough for people to recognize someone as one type of artist and then–

BRODY: I understand it. I’ve experienced it, because I’ve shown work publicly since 2015 or so. And I was surprised by that. I don’t know why I was, but I was and now I’m not. Now I understand it more. I understand why people like to compartmentalize things and people, right?

SANDSTROM: Right.

BRODY: “How old are you? Are you Jewish? What education do you have? Or where were you raised? What’s your socio-economic background?” And we formulate an opinion or an idea of who you are as it correlates to us. “Are you a dramatic actor or you’re a comedic actor? Oh, you’re doing comedy. That’s interesting. You paint, you make music. Oh, weird.” I’ll speak to people and they’ll be like, “Oh, Jim Carrey paints,” or they’ll say “Sean Penn paints.” Lots of creative people need creative outlets, right?

SANDSTROM: Mhmm.

BRODY: And this came to me before an understanding and a knowledge of acting. And my father’s a wonderful painter, he’s a more talented figurative fine art painter than I could ever be. And yet he doesn’t show or sell anything. But he’s a teacher. He’s a public school teacher, but he’s a painter. So I’m playing music tonight, I’ll be playing a soundscape that I’ve created that is a whole compilation of years of my beats, and similarly draws from similar inspiration of old advertisements and cacophony of the city. To create an auditory soundscape almost shares a similar layering process that I apply towards all my work, whether it’s acting or making music or painting. It’s kind of an unpacking of things, a frame of reference and a guide for me to process them all.

SANDSTROM: That’s so wonderful. Do you know who collects your art and who’s the actual–

BRODY: I have a number of serious collectors.

SANDSTROM: And do you think some of that is driven by fandom?

BRODY: No, no. I mean, some people I’ve encountered through my life and travels, and they were surprised to gain an understanding of my work and like my work. Now, I can’t completely shed how people may perceive me at this point in my life, but the work is really pure and from me. Whether I did anything else, and if you could kind of watch it with those eyes, I think it’d be better to take those blinders off and just see someone who’s in referencing all of our influences and violence in society and how since birth how ubiquitous it all is, we’re inundated with imagery and cartoon imagery and acceptance of all of this fast food and mass media and all of it that kind of we’re feeding.

SANDSTROM: Right. And you did those guns a while ago.

BRODY: Yeah. It started then.

SANDSTROM: And the Starbucks works.

BRODY: I did a show called Hot Dogs, Hamburgers, and Handguns, and this is an evolution of that. It’s an evolution of my own vocabulary, of my ability to convey my thoughts in visual imagery with a much more textural layer, and it speaks to the New York that I grew up around. Old tarnished walls [touches artwork] and finding beauty in what’s kind of degraded and imperfect rather than trying to paint a perfect painting and have it pristinely framed and mounted. It’s like, I can live with these. I can live with finding the nuances and hidden images and things that I see in it on a wall for years, even in my own home, whether someone appreciates it or not, I do. This piece has been up in my living room for three years.

SANDSTROM: It’s so fun. Thank you so much for your time.

BRODY: My pleasure.