Adam Pendleton and Venus Williams on When Passion Becomes Profession

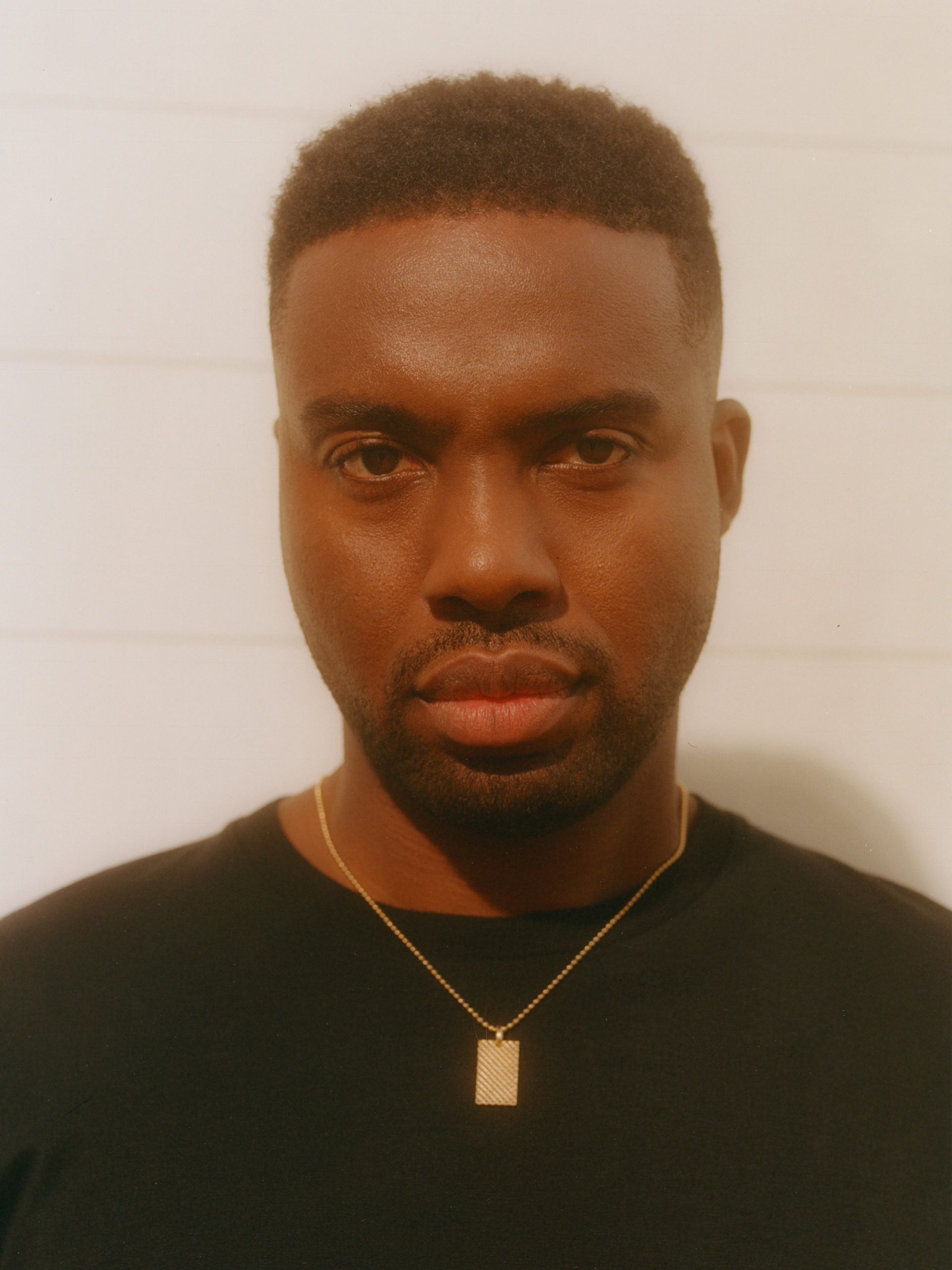

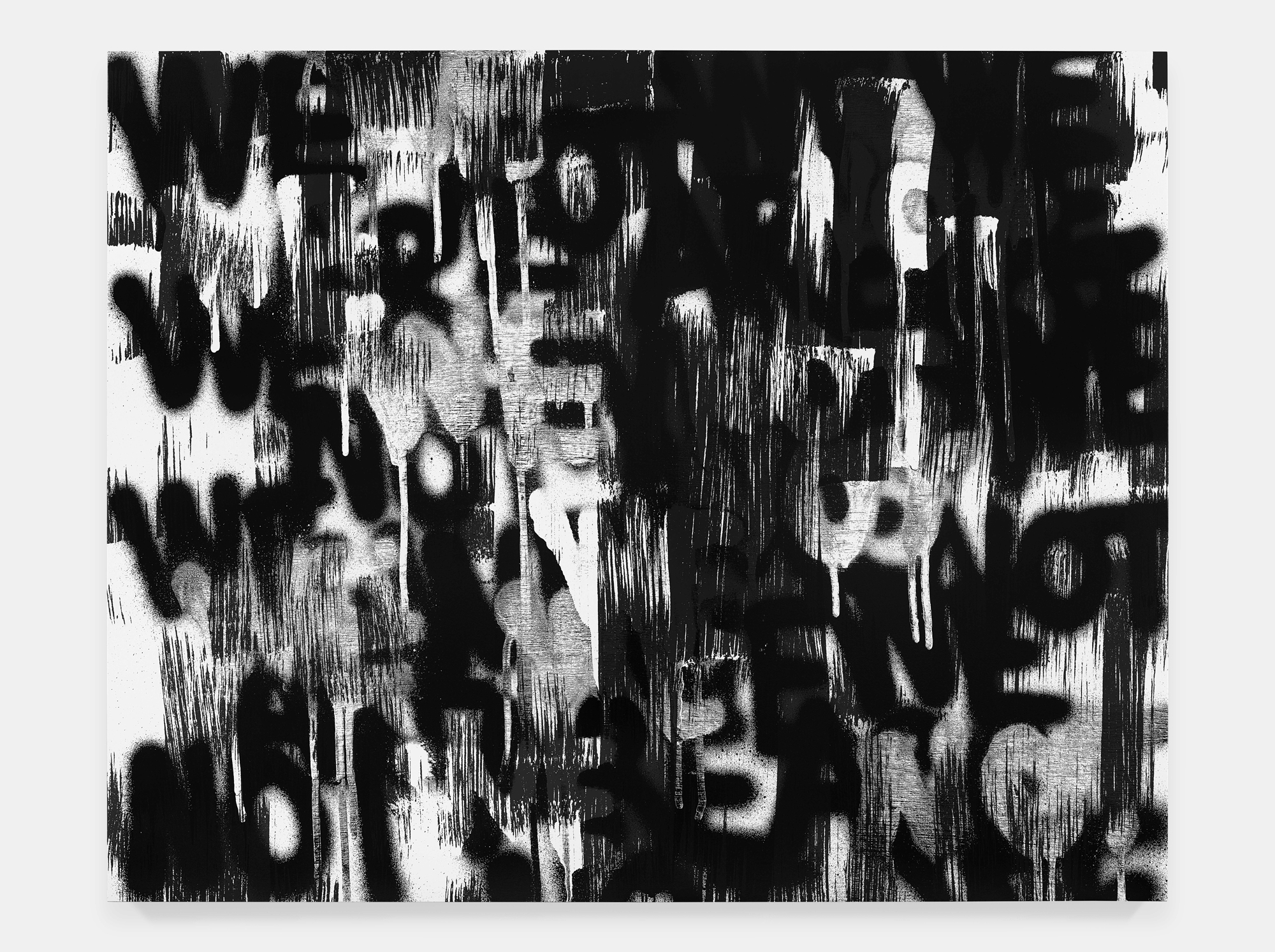

No contemporary artist embodies the spirit of Walt Whitman’s declaration “I contain multitudes” more potently than Adam Pendleton. Across his bold, compressed, densely piled surfaces spill words, fragments, rally cries, commands, defiant chants, civic demands, graffiti, broken poetic syllables, and blown-apart letters, all competing in a visual-linguistic cacophony that feels like a snapshot of our loud nation in the present tense. The 37-year-old, New York–based artist is a prodigious talent whose multidisciplinary corpus ranges from performance to photography, but he is particularly celebrated for his graphic, black-and-white screen-print paintings, sometimes covering entire walls, collaged and layered with so much visual complexity that they often take on the dimensionality of sculpture.

In the past two decades, Pendleton has built a career that bridges so many seemingly incompatible realms—formalism with political activism, the visceral energy of abstract painting with hyper-tuned socio-historic concerns, the living messages of grassroots movements such as Black Lives Matter inside the institutional structure of galleries and museums. The artist seems almost single-handedly to be redefining the role of the artist for our current age. This past spring, Pendleton’s alchemy filled the lobby of New York’s New Museum with paintings of protest language and images of masks stamped directly on the walls. This summer, he joined forces with the British architect and sculptor David Adjaye for a show at Pace Gallery in Hong Kong (Pendleton has been a longtime practitioner of dynamic artist collaborations). And this fall, in the atrium of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Pendleton is creating a solo exhibition entitled Who Is Queen?, which will include some of his biggest and most political paintings to date. Pendleton, who splits his time between his house in upstate New York and his home in Brooklyn, is a man on the move, and his projects extend to causes such as helping (along with a few of his fellow artists) to preserve Nina Simone’s childhood home in Tryon, North Carolina. But even on the go, he is always thinking about art. In 2014, Venus Williams bought one of Pendleton’s paintings to add to her prominent art collection. In honor of his upcoming MoMA show, Pendleton spoke to the tennis legend about the power of words, the promise of Black Lives Matter, and why it doesn’t feel like work if it’s a passion. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

VENUS WILLIAMS: One of the parts of your career I find most interesting was how young you were when you started out. You were just 16 when you went off to Italy to study art. I connect with that because I started my career early, too. I was 14 when I played my first pro match, so I totally relate to being young and wanting to be taken seriously. What was it like starting so early?

ADAM PENDLETON: I do think that’s something we share, that sense of our professional lives starting at such an early age, when other people are still very much involved in the process of self-discovery. Somehow, I found what I wanted to do with my life—or it found me. It’s hard to say how that happens. I finished high school two years early and, like you said, went off to Italy. I was 18 when I was in New York and beginning to show my work in galleries. I did my first show at a gallery, Yvon Lambert in New York, when I was 20 or 21. I had to be coy about my age because I was always hearing people refer to artists who were in their 30s as “young artists.” I thought to myself, “Well, if that’s a young artist, then what am I?” I thought I should keep quiet about my actual age and just go about my business. Looking back, I feel fortunate to have been so clear about what I wanted to do, not only professionally, but with my life, because it’s much more than just a profession. It’s a guiding light, a guiding path. It gives clarity and purpose to everything that I do.

WILLIAMS: I relate to that, too. I don’t think I was meant to be doing anything else. What were your early influences? I read that your mother told you as a kid, “When you buy a book, you’re not really spending money.”

PENDLETON: I think it all starts with the parents, doesn’t it? And it’s funny that a small thing that someone says can shape your entire life. My mom planted that seed about books in my head. Maybe what she meant is that you’re acquiring so much more than money when you pick up a book and learn about something. I would absolutely attribute my love of language and my love of books to my mother and growing up in a house where we talked about literature and writers, ranging from Toni Morrison to Adrienne Rich. That, absolutely, gave me away into the visual arts. And something that has carried on through the many years I’ve been making art is the tension between text and image, and how these distinctions can become conflated.

WILLIAMS: It’s interesting that the roots of visual art comes through words and language.

PENDLETON: Absolutely. Language is an oral tool, but it’s also a visual tool. It’s what I would call an organizing principle, but it also points to the complexity of the world we encounter on a daily basis. We’re always trying to make sense of the world around us through language, even if it’s an impossibility. What I particularly like about language is the tension between representation and abstraction. Sometimes when you’re reading something, it can just look like a mark or a line, and that grounds the reader as a site of engagement.

WILLIAMS: How did that love of language carry over into your early years as an artist in New York? Did you know what you were doing right away?

PENDLETON: It’s a question I could ask you about being 14 and playing your first pro match. I think one of the gifts of being young is that you don’t even realize that you’re taking a risk. Do you know what I mean? You just seem to say, “Yes, of course I’m going to do this.”It’s only later in life that these kinds of decisions become much more complicated.

WILLIAMS: That’s the great thing about youth: You can take a risk without thinking too hard about it. And it really is a blessing.

PENDLETON: It’s an absolute gift. As an artist, I try to retain that idea of risk, while also giving it shape and structure. Every day when I go into the studio and start on a work of art, I’m taking a risk. I’m willingly throwing myself intellectually, emotionally, into the unknown.

WILLIAMS: Growing up, my dad used to say, “Always try something different, always do something new.” That’s a risk.

PENDLETON: Exactly.

WILLIAMS: Over the past year, there’s been a lot of positive momentum in the Black Lives Matter movement. How has that impacted your work?

PENDLETON: What’s really struck me is the durability of the Black Lives Matter movement. I think when that language took hold of the public consciousness, in 2012, there was this feeling that perhaps it was fleeting, that it would come and it would go. I actually adopted that language or brought that language into the space of my work very carefully, I will say, because as an artist, I don’t respond to the news. I try to make sense of the world at a much slower and more deliberate pace. But there was something urgent about that language and I wanted to slow things down and really make sure people were listening to all that Black Lives Matter implies. I’m really gratified that the ideas, issues, and concerns to which that language gave voice in our contemporary moment have proved to be so durable, and that people are still contending on a social level, on a political level, and also on an emotional level with what that language proposes about how we should be thinking about American history and society as we live it and confront it every day.

WILLIAMS: When Black Lives Matter really started to gain momentum during quarantine, I, too, wanted to understand what it meant. A lot of people told me, “Venus, you should say something.” And I said, “I want to absorb it myself first. I don’t want it to be a trend or simply marking it as an Instagrammable moment” I relate to having the need to gather your own feelings first, before you are able to create something that matters.

PENDLETON: One of the reasons I think art can be so useful at certain moments, especially in a political sense or context, is that art slows things down. We look at the same paintings or listen to the same music not just for a year or two, but for hundreds of years. People still travel all over the world to see specific paintings. That durability fascinates me. And I think for things to change for Black people around the world, it ultimately has to be a test of time.

WILLIAMS: Your work is a part of the collections of major institutions like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate in London, and you’ve been vocal about how the need to incorporate Black artists in museums is long overdue. Now, finally, Black artists are getting their due. But it’s still overwhelmingly white work. What is your role as a Black artist within that context?

PENDLETON: It’s really complicated. There have been moments in modern and contemporary art where culture has really turned its attention to Black artists—take Sam Gilliam or Adrian Piper or David Hammons or Alma Thomas or Howardena Pindell or Lorraine O’Grady. But what they didn’t e-joy was the sustained attention that someone like, say, Gerhard Richter has enjoyed over the many decades that he’s been an artist. My hope is that we’re not on the cusp or the wave of another fleeting moment where people recognize what Black people have to contribute to visual culture, but that we’re really turning the page and that it will be a sustained engagement. That our contributions will not just become a part of the narrative, but that they will change the narrative.

WILLIAMS: That’s very powerful. I’ve had an opportunity to see so many amazing works by Black artists and I love being a part of it, not as an artist, but as an observer, living it and absorbing it.

PENDLETON: I know you’re a collector because you have one of my works! Are you collecting art these days?

WILLIAMS: I am. The title of the work I have of yours is, “A Woman on the Train Asks Angela Davis for an Autograph.” Can you talk about where that title comes from?

PENDLETON: It’s a line from a poem titled “Albany” by the writer Ron Silliman. It’s from a book where he wrote a poem for every letter in the alphabet. Albany is A. His poetry is unusual in the sense that he almost uses it as a conceptual device to collect and assemble language. He’ll put a lot of sentences together that would, at first glance, not necessarily make any immediate sense. This sentence was one of them: “A woman on the train asks Angela Davis for an autograph.” It might seem like an odd title when you see the visual reality of my piece, but I like nonsense. Art isn’t necessarily about making sense. It involves the willingness to be misunderstood. I think we all need to be more willing to be misunderstood.

WILLIAMS: If we’re willing to be misunderstood, it means we’re willing to be true to who we are, even if someone doesn’t get it. I like that. You have a major show coming up at MoMA in the fall, which I really hope I get to see. It’s called Who Is Queen? That’s another great title.

PENDLETON: Every day, all I think about is, “Who is queen?” I think that goes back to this idea of how we move through the world and how we’re understood. That’s some of what the title speaks to. “Queen” can be a name for a queer person, an effeminate queer man. People will say, “Oh, he’s such a queen.”I remember someone said that to me at a particular moment in my life when I thought I had done away with such things, when no one would say something like that to me. So there’s a tension between what we want to embrace and what we want to refuse at any given moment, what we want to name, what we want to claim, who we want to be, who we don’t want to be—all of these declarations that we’re forced to make in the world at any given moment. But a queen, of course, if we take it out of this particular context, also symbolizes power and authority. I liked that duality. For this show, I’m really thinking of it as an occupation of moments, a structure within a structure. I’m showing works I’ve done over the years and some new works as well, including the largest paintings that I’ve done to date.

WILLIAMS: What’s your creative process like?

PENDLETON: I’m a compulsive note-taker. I’m always writing down visual ideas. These things I write down, or take photographs of, often find their way into a work. My work life is very ordinary. I’m a 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. kind of person. I get up and go to work like anybody else, I probably just stay longer. I never wait for inspiration. You have to claim it. You can’t wait for anything.

WILLIAMS: Are you a collector yourself?

PENDLETON: Oh, yes. I buy all kinds of things. I can’t help myself, Venus. I’m sure you know how it is. Once you start, you just can’t stop. In terms of art, from Mel Edwards to Stanley Whitney, when I see it, I try to buy it. I have some photographs by Lorraine O’Grady. And that’s really just the tip of the iceberg. I also recently got a piece by Richard Tuttle.

WILLIAMS: Do you enjoy putting on exhibitions all over the world?

PENDLETON: I do enjoy it! I love going to other cities, be it Seoul or London or Hong Kong or, maybe my favorite city outside of New York, Paris. And of course, Paris has great food. If you’re ever in Paris, go to a restaurant called, yam’Tcha. It’s probably one of the best meals you’re ever going to have, with unparalleled culinary creativity. I also like more traditional places that have been around for a really long time, like Zuni in San Francisco. I think food is an art form, and it’s something that I really love celebrating and engaging with, alongside my husband.

WILLIAMS: It sounds like food is your happy place.

PENDLETON: It adds much joy. I’m really hoping that when we come out of this pandemic, that we don’t lose so many of our restaurants, because they’re such important cultural spaces where so many memories are made. They’re incredibly important.

WILLIAMS: Okay, here’s my last question: What do you do for fun?

PENDLETON: I’m very focused on my work, and work is what I do for fun. Outside of that, I like quiet places and quiet spaces. I love leaving the city and going to upstate New York to cleanse my palate, so to speak.

WILLIAMS: Are you and your husband similar in that way?

PENDLETON: I would say we’re similar. He wasn’t as enthused in the beginning about spending more time outside of the city. But now, I think he would spend more time outside of the city than I would. He would deny that, though, Venus. But I’m work and family, that’s who I am.

WILLIAMS: Work, when you love it, doesn’t feel like work. It brings you joy.

———

Grooming: Laila Hayani